It was described as “A SQUALID CRIME” , a grim murder , subsequent court-case and sensationalist newspaper coverage which gripped the public imagination . While the names of the victim and perpetrator have long been forgotten , the murder was so infamous at the time that it led to a street name been changed to help erase the memory of the crime. Here is the full story :

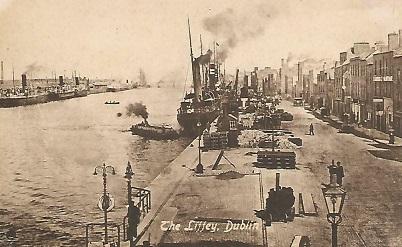

It was unusual for the SS Olive to be on the Liffey. Built in 1893 for the Laird Line’s Glasgow, Dublin, and Londonderry Steampacket Company she usually served the Derry route, although her limited accommodation of 100 beds meant that even on the Maiden City route her appeal was limited. She could, however, handle up to 1000 deck passengers (but even this would eventually see her replaced in 1930 to provide a more comfortable and lucrative mode of travel between Ireland and Scotland). Besides passengers she also carried livestock and general merchandise.

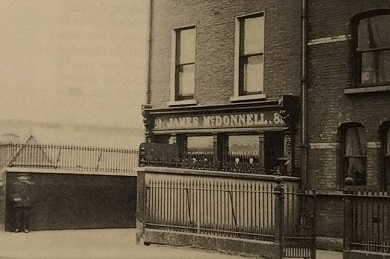

Passenger ships engaged on the Dublin to Glasgow route were known locally as “The Scotch Boats” and moored close to the Fish Street and North Wall Quay junction as the Laird Line’s warehouse and offices were nearby. Early on Saturday the 7th November 1908 several men approached the crew of the Olive. They were Scottish and had been sailing with the Baron Kelvin, a screw steamer Cargo Ship which had been trading between Algeciras near the Bay of Gibraltar in Spain and Ireland. Having returned and unloaded their cargo the previous day on City Quay, six of the crew, not being required for the subsequent voyage, were paid off. Seeking a way back to Glasgow they were directed across the river on the Ferry to obtain passage home on the Scotch Boats. Having obtain berths and loaded their luggage, the young men aged between 19 and 26, set out to find nearby entertainment while they awaited the departure of the ship. Flush with money , which was burning a hole in their pockets, some returned to City Quay and began to drink in nearby pubs with the remaining members of the Baron Kelvin crew while others stayed on North Wall Quay, as James McDonnell’s pub was just a few feet from where the Olive was moored. It would be an eventful evening before they set sail for Scotland.

Around 6.00pm two of the Scots, George Robertson and John Peterson, somewhat the worse for drink, boarded the Olive and promptly began to sleep off their oncoming hangovers. The other four, David Anderson, Neale Gillies, Alexander M’Donald and Thomas Grant continued to drink the final hours away at McDonnell’s before the ship sailed at 10.00pm.

McDonnell’s had a snug, a self-contained compartment with a door and a window giving access to the bar counter so that the more excessive behaviour of the male customers could be avoided. In Dockland’s parlance this was sometimes known as a “Confession Box” and was usually installed for “the auld wans”, older women of the area who liked a drink. Younger women looking for alcohol would either go to a Spirit Grocers or would send a messenger in with a jug or can, to be filled with porter to be drunk at home. Women who went into pubs unaccompanied at that time were usually seen as being of poor moral standing or possibly prostitutes. Unusually on that evening in 1908 three unaccompanied women were drinking in the pub’s snug.

The women lived at No 1 Elliot’s Place a short narrow street which connected Montgomery Street with Railway street in the heart of the infamous Monto Red Lights District. Kate “Christy” Kenny was 38 and had a record of convictions for Sheebeening [running an unlicensed drinking house] and prostitution going back to 1900. (In 1909 she was charged with keeping a brothel at 17 Gloucester Place. Three years later she was arrested for larceny with three others at a brothel in Summerhill, but the case never came to court as the charge was withdrawn). Fanny Langford, aged 34, had been arrested with four other girls for the larceny of £47 in 1905 while working at a brothel in Summerhill run by Thomas and Jennie Blaney. Langford, who seems to have been the ringleader, received the harshest sentence of four months hard labour. Her convictions for prostitution would continue up to 1909 and her arrest records suggest that for much of her life at this time she was homeless or of “no fixed abode” except on the few occasions she was arrested in an Elliott Place Brothel. She died the following year. Both women had been caught up in mass arrests in July and October 1908 as the Dublin Metropolitan Police targeted the brothels, kip houses, and sheebeens of Elliott Place. This may have motivated the women to seek out “safer” pastures outside the gaze of the authorities as North Wall Quay was some distance from The Monto. Prostitution wasn’t unusual in the Docklands area in 1908 mainly in the pubs and areas in the vicinity of City Quay on the southside of the river where numerous ships unloaded their cargoes. However, it was rarer on the northern side where the cross channel passenger services were located. The third woman, Mary Carroll, was a 36 year old widow who had once lived nearby in Nixon Street off Lower Sheriff Street and Common Street. There is no evidence to suggest she was involved in prostitution, but the newspapers would still describe her as being “a miserable outcast” and of “that unfortunate class” of women. The Scotsman Newspaper would also incorrectly label North Wall Quay as a notorious part of Dublin.

Aerial shot of Fish Street (Castleforbes Road) in the 1930′s. McDonnell’s pub is the white building on the bottom left

Around 9.00pm the women left the pub followed soon after by the Sottish Sailors. M’Donald and Gillies went aboard the SS Olive while Anderson and Grant after some conversation with the women at the street corner walked into the darkness towards Mayor Street and Upper Sheriff Street. Fish Street (now Castleforbes Road) cut through the centre of the 14 acre site of the various departments of T. & C. Martin’s Timber Works. The street was poorly lit and large consignments of timber were often left along the roadside near waste ground as there were few houses at the Quay end of the street being largely works yards and warehouses.

Thomas Grant, an able seaman who had been part of the Baron Kelvin’s crew barely made it up the gangway as the SS Olive prepared to sail. Questioned by Neale Gillies, Grant claimed that he had been delayed by an occurrence involving one of the women whom he said had been “crushed” or assaulted during an incident involving some soldiers. Gillies found this strange as he hadn’t seen any military on the North Wall however he soon found that members of the 18th Hussars were on board the ship. Still, he found it suspicious that Grant asked him not to mention it to anyone if he had not been involved in the affair.

Kate Kenny had been returning towards the Quay when she saw the prostrate body of Mary Carroll. There was no sign of struggle but there was blood coming from her mouth and nose. Kenny screamed for assistance. David Anderson who had been with Kenny heard her cry out and ran to find Carroll’s lifeless corpse on the waste ground near some logs on Fish Street. Anderson thought he saw a gag in her mouth but couldn’t be certain. They quickly alerted Constable McCarthy who was on duty on the docks that evening. McCarthy attempted to phone the Corporation Ambulance from McDonnell’s pub but the phone at the premises was out of order. A local postman suggested he try the one at the nearby Laird Line Offices. Meanwhile Anderson, hearing the whistle which announced the imminent departure of the Olive ran down the street to catch his ship.

It was 10.30pm when the body arrived at Jervis Street Hospital where Dr. O’Sullivan, the House Surgeon, carried out a brief examination. Carroll had been ill for some time and it was initially believed that her death was caused by haemorrhage of the stomach. O’Sullivan had her admitted to the mortuary while awaiting further instructions from the Coroner. It was only while carrying out a post-mortem the following day that he discovered that Carroll had been stabbed with a long sharp blade to a dept of about 6 inches which punctured her right lung. O’Sullivan’s conclusion was that a single blow of great force had caused her death. The blade had been withdrawn so quickly that the blood had rushed into Carroll’s throat making it impossible for her to raise the alarm although it was subsequently discovered that she had attempted to crawl back towards the pub before losing consciousness. This was not death by natural causes. This was murder.

Kate Kenny described the man with Carroll as elderly, about 60 years of age, with white hair and wearing a dark overcoat and hard hat. She claimed to have been no more than 12 yards away and heard no screams or sounds of struggle. Langford was unable to give any description; however, Kenny’s assertion was somewhat verified by a local youth named Michael Lovatt, who would play a role in subsequent events.

Investigating the murder fell to Detective Sergeant Andrew Lonergan. A Kilkenny man, he had joined the DMP in 1891 later transferring to the Detective Section of G Division in 1896. He had recently been promoted to Detective Sergeant and this would be a case that would enhance his growing reputation which would see him finish his police career as a Detective Inspector. Up to then most of his work involved investigating racing frauds, pickpockets, and counterfeiters. He would be particularly noted for his clever employment of forensics in this case which was still a developing science. Lonergan quickly circulated the description of the elderly man given by Kate Kenny who allegedly ran off in the direction of Upper Sheriff Street. However, he quickly detected that the Scottish sailors who had been in company with the women may have an involvement and passed details onto the Police at Glasgow. Within days the Glasgow Police had tracked down the former crew of the Baron Kelvin and brought them in for questioning. It had taken some effort as they had dispersed across Scotland on their return but by the 11th November five of the men had been tracked down and brought to Glasgow under caution.

A sixth man had left word at his Glasgow lodgings that he was visiting friends at Leith near Edinburgh which the police quickly found to be untrue. However, they did find his kit bag which contained the sheath from a dagger and a sweater with what they believed to be three small bloodstains on the sleeve. Their suspicions aroused, after some intense investigation by Detective Inspector Thompson French, they found that he had actually gone a short distance from Glasgow to a house on an isolated road outside Holytown, Lanarkshire, where French effected his arrest. Lonergan, accompanied by 14 year old Michael Lovett, travelled to Glasgow to attend an identity parade of the suspects. Lovett, whose account of events Lonergan would later describe in court as “something of a Fairy Tale”, quickly identified Gillies and M’Donald and arrangements were made for their transfer to Dublin with the other four Baron Kelvin crew members. The murder had attracted a lot of coverage and the court room was packed to capacity. However, when they were brought into the court to be charged, there was something of a shock for those assembled there. Far from being a white haired 60 year old, the man being charged with Mary Carroll’s murder was the 25 year old, brown haired, able bodied seaman, named Thomas Grant.

Grant was from the Shetland Islands and had joined the 147th Battery Royal Field Artillery on 28th June 1901. Army life didn’t agree with Grant and he deserted on the mouth of Christmas 1902. He returned to the service four months later and after a short prison sentence was dismissed “as no longer required.” Since then he had worked for some years on the American Coasting Service before returning to Scotland. Although he would claim to be single it was subsequently discovered that he was married with a wife named Jessie and a young child. As with most of Grant’s statements during the investigation he was consistently economical with the truth unless proved otherwise.

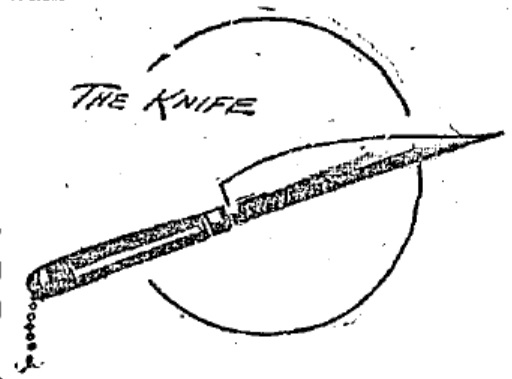

While being examined at Glasgow it transpired that he had purchased an unusual double edged knife from a Spaniard at Algeciras as a present for John Green, grandson of a friend’s mother, at whose house at Holytown, Lanarkshire, he was arrested and the blade recovered. Bizarrely he had produced the knife a number of times on the journey back to Glasgow on one occasion offering it to Neale Gillies to cut bread. He later showed it to a Private George Morrison of the 18th Hussars in the hope of impressing him. The design was unusual and distinctive and seems to have fascinated Grant. Various testimonies at his trial have him fondling it and almost being hypnotised by it. Grant also possessed a small folding pocket-knife, but it was the murder weapon that he consistently produced to show people. It’s distinctive and unusual design was remembered by all who saw it and its shape was consistent with the wound which killed Mary Carroll according to Dr. O’Sullivan. The Doctor described it as a “formidable” weapon.

John Anderson had seen Grant alone in a doorway on Fish Street “as if waiting for someone” shortly before Kate Kenny discovered Mary Carroll’s body. Tackling him on the voyage to Scotland he claimed Grant had shown him the knife and said that Carroll had attempted to “get through him” a euphemism for attempting to pick his pockets. However, the lack of evidence of any struggle cast some doubt on this. Anderson told him that he’d found her dead body on Fish Street to which Grant replied, “It was me, don’t tell anybody.” When Grant’s address at Glasgow was searched his kitbag was found within which was a sweater with three small red stains. It was difficult to say if these were blood stains, and professor M’Weeneys investigations would subsequently prove they were not, but it motivated Lonergan to have the Spanish Blade examined by experts. John Green, the child who had been given the blade as a present, had cleaned it with emery paper, removing any potential external evidence of its use in the murder. However, a cutler on taking the blade apart found traces of what he believed were blood corpuscles under the two sides of the handle. On examination under a microscope by Professor M’Weeney it was confirmed that it was human blood stains and that they were recent. No less than five or six weeks old. M’Weeney claimed they were preserved by Grant keeping the blade in his pocket. Grant’s defence would claim that the blade was second-hand, and that Spaniards used blades the way “Irishmen used their fists”, but this evidence was damning.

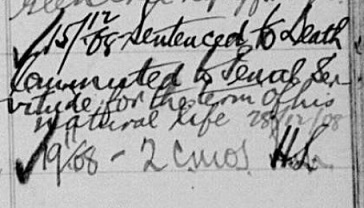

Ultimately the case came down to whether the jury accepted John Anderson’s account of Grant’s confession aboard the SS Olive or the Statement of Kate Kenny who said she had never seen Grant before when asked to identify him in Court. Fanny Langford’s inability to provide any description also created doubt in the jurors’ minds. Anderson, aged 19 at the time, having been arrested at his home in Ardrossan, believed he was going to be charged with the murder and gave a statement to the Glasgow Sentinel Newspaper implicating Grant. It was only after he entered the dock at Dublin that he found out he was there purely as a witness. After some deliberations the Jury brought in a verdict of wilful murder with a recommendation towards mercy. In Passing sentence Justice Wright advised Grant that he would not give him any false hope of a reprieve and somewhat emotionally passed the sentence for Grant to be hanged at Mountjoy Jail on the 12th January 1909. Grant seemed unable to comprehend the implications of Wright’s sentence.

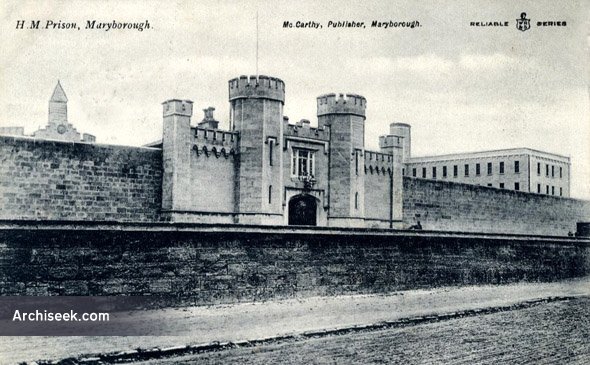

Almost immediately Grant’s defence council, J.G. Lidwell, instigated an appeal for mercy announcing that he was preparing a memorial for the Lord Lieutenant and requesting members of the public to sign it at his offices on Ormond Quay. Having submitted five separate memorials on Grant’s behalf Lidwell receive confirmation on the 28th December 1908 that Grant’s sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life with the sentence to be served at Maryborough [now Portlaois] Prison.

In January 1909 Grant began what should have been a life sentence at Portlaoise Prison. He seems to have been a model prisoner and was recommended for special privileges during his time there. It’s probable that with the excessive amount of drink taken that Grant had killed Mary Carroll in a moment of madness which he later regretted. On 25th April 1917 after only serving eight years of his sentence Grant was released under license and returned to Scotland.

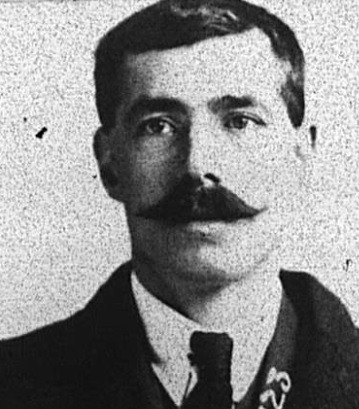

Having been released Grant set about putting his life back together returning to the Merchant Navy and serving as an able seaman for the remainder of the First world War for which the above photograph was taken. There is something haunting about the image as if the life has been drained out of him. Given the amount of alcohol consumed by all parties it’s likely that Grant would be charged today with manslaughter and possibly have served much the same amount of time as he did in the early 20th century. The swiftness of the blow and absence of any evidence of a struggle suggests it was a momentary reaction carried out without any thought or premeditation. While its commendable that so many Dubliners supported J. G. Lidwell’s memorials on Grants behalf, it was also symptomatic of the class system of the time which saw the likes of Mary Carroll as worthless or as the Irish Independent described her, “a miserable outcast.” She consorted with prostitutes and thieves who had records for robbing customers in the brothels they worked in, so Carroll was seen as more of the same even though there was no evidence to suggest she was guilty of either.

Today all the protagonists in the story have faded from memory. At the time it had been widely reported not just in Ireland but had received extensive newspaper coverage throughout Britain where it was often described as “The Dublin Tragedy.” While that title was appropriate, the sordid story of illicit sex and murder lingered long in relation to the area. Fish Street and that part of North Wall Quay would acquire an unwarranted reputation largely based on the infamous murder on the night of 7th November 1908 when three women seeking a quiet drink encountered some Scottish sailors awaiting a Laird Line ship. In 1924 local merchant John Hughes would organize to have the name of Fish Street changed to Castleforbes Road thus wiping out the last link with the infamous murder and restoring the reputation of the street which he felt it deserved.