In June 1903 the DMP raided a house at 12 Upper Oriel Street. The object of their attention was the resident of the top floor flat, Daniel Courtney, who was running an illegal sheebeen from the premises. Courtney was a Casual Grain Labourer on the Docks and sought to extend his young families precarious income by some extracurricular home brewing. Tried in the Northern Police Court on the 16th June, he was sentenced by Judge Swift to one month’s imprisonment or a £10 fine for “selling porter without a licence.” This was the equivalent of about a month’s wages – a huge sum at the time. Courtney had no choice – he became prisoner No. 110 in Mount joy Jail. A decade later, he was involved in the 1913 Lockout and evicted from his house in East Wall. In 1916 he was an Irish Citizen Army soldier in the Easter Rising, seeing combat at Annesley Bridge, the GPO and present at the surrender in Moore Street. As we mark the centenary of the founding of the Irish Citizen Army , this is his story, as told by Hugo McGuinness.

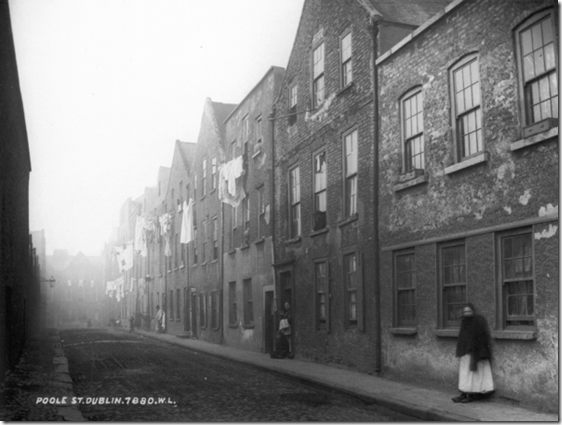

Daniel Courtney was born in the old Weavers district of Dublin at 19 Poole Street on the 18th September 1865. It was a street of cramped dilapidated buildings prone to regular outbreaks of fever and disease. The 1901 Census shows there were five tenements with up to three families living in each. Previously they lived at 10 James Street a seven tenement house where a number of his siblings had been born. While still a child his family moved to Britain Street (now Parnell Street) continuing a nomadic existence familiar to many working class Dubliners. Addresses were linked to employment and loss of a job usually meant a change of home either through an inability to pay the rent or seeking opportunity in a new part of the city. The Courtney’s seem to have spent some time in Britain Street as Daniel would later recall the street as the place of his childhood. Eventually Courtney and his family would come to live in the North Dock district.

Little of his early life is known until he married a County Wicklow woman named Julia Doyle on 16th September 1888. His family were living at 4 Greaves Cottages, Newfoundland Street, while Julia was working as a domestic Servant in a house in Rathgar. Shortly afterwards they moved to 2 Tighes Cottages, Mayor Street, located between the modern Luas line and Crinan Strand. This was an area of high density, cramped housing, with little sanitation. In the 1880s there had been six cottages but more had been added by the time the Courtney’s arrived there. By 1901 the census shows 19 premises housing 29 families. They later moved to No. 9, a small two roomed dwelling, which they shared with the White family, a total of 11 people in two small rooms. Four of the seven children born to Daniel and Julia between 1889 and 1906 would die before they reached their third birthdays. Their second last child, Caroline, died when she was 9 months old.

Not surprisingly as his employment prospects improved the family moved the short distance to 12 Upper Oriel Street. Courtney was literate and his census return shows a neat, confident hand, which may have contributed to his rise with the Merchant’s Warehousing Company to the job of Tally Clerk. This involved keeping account of grain as it was loaded on and off ships and trains and was a position of some responsibility. The family was on the up, comparatively speaking, and their last child, born at Upper Oriel Street, was Julia Mary Love, possibly named as a symbol of their improving good fortune.

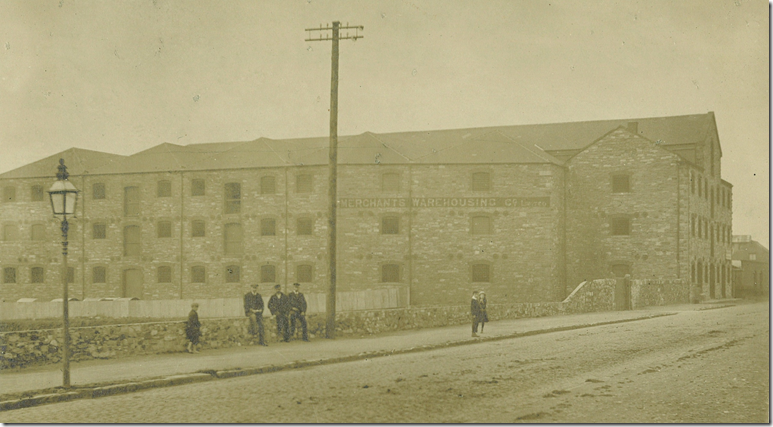

In 1907 the Merchant’s Company began building houses for their employees. Each premises contained two family houses with three tiny rooms each, with rents of 4/6 for the larger upstairs rooms and 3/6 for the downstairs. Writing of these houses in 1913 James Connolly pointed out that having an employer as landlord was dangerous and it appears many of the occupants had been coerced into them. Even long serving employees were aware, according to Connolly, “that if they left their jobs they would lose the shelter over the heads of their families” and were told if they refused to move in they would be dismissed. The Courtney’s soon found themselves the tenants of Number 1 Merchant’s Road.

Unlike many of his future Irish Citizen Army colleagues Courtney was on the electoral register, appearing on the rolls for 1908 at Upper Oriel Street. He may have been doing comparatively well compared to some of his neighbours but having lived the life he had, was aware of how easily it could change. He was somewhat late in joining the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), signing up on the 5th April 1911, Badge No. 4017. He may have been attracted by the fact that having started to unionise the Merchant’s the ITGWU had recently won a 2 shilling a week increase for their members. As a dock worker he would have been aware for some time of Big Jim Larkin and must have heard his fiery speeches as he revolutionised the docklands to improve the lot of the ordinary worker. Whether through his job as Tally Clerk or natural leadership he found himself playing a role with the Tallymen’s Section of the Union, and appeared on delegations to the Number 1 Branch on behalf of members in the Merchant’s Company Section during disputes.

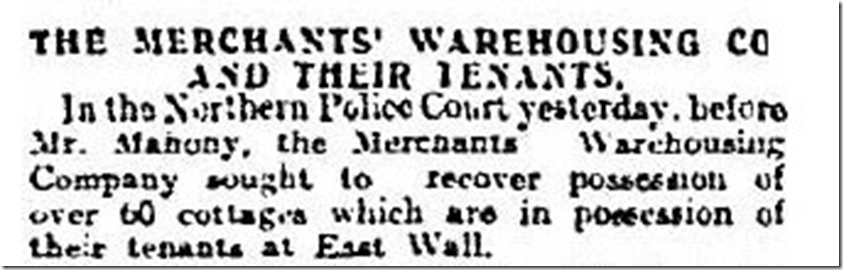

Lack of documentation means we know little of his activity during the Lockout of 1913, however he must have played a part in organizing the sympathy strike that would have such a tragic conclusion. As the men went on strike, Free Labour or “Scabs” were brought in from Co. Meath and Manchester and the Merchant’s Company decided to evict the striking occupants of Merchant’s Road to accommodate them. The ITGWU provided legal representation to the strikers, but eviction notices were issued against 62 workers and their families. On December 4th, sixty of these were served. Julia Courtney was seriously ill at the time that the eviction order came through. The Bailiffs fearing she might die decided to leave the Courtneys to another day. They were one of only two families to survive immediate eviction due to illness but by the New Year they were gone from Merchant’s Road. After nearly a decade of full time employment Daniel was back in the scramble for temporary work as a casual Docker. The family moved to a room at 45 Bessborough Avenue and Daniel joined the 1st Company of the recently formed Citizen Army.

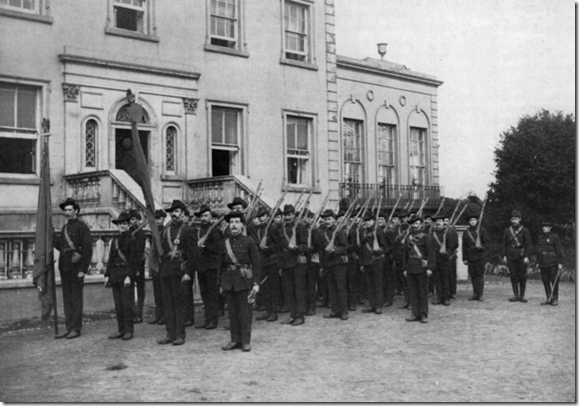

The ICA, founded following James Connolly’s notorious “I want to talk sedition” speech at Beresford Place on the 13th November 1913, was originally set up as a workers protection force against the brutality of the DMP. By 1914 their aims had changed somewhat, and as James Connolly’s influence grew, they veered more and more towards a revolutionary organization aiming for the Independence of Ireland and the founding of a Worker’s Republic. Despite the uncertainty of his employment Courtney continued to play an active role in both the ICA and the Transport Union. The army was a volunteer organization and it’s members so poor that weekly subscriptions were set at one penny. On top of that members had to contribute to pay for their uniforms, rifles, and ammunition for practice at the ranges at Thomas Street, Liberty Hall, or the ball cartridge range at Croydon Park. Camping weekends were organized at Croydon Park for which members had to contribute a shilling to cover a substantial breakfast and entertainment. It was a huge commitment and many fell by the wayside. In 1916 Julia Courtney claimed that Daniel brought home 35 shillings a week on the docks which must have involved an enormous effort by someone casually employed. Yet he still found time to attend ICA training and marches. During the reorganization of the army in the winter of 1915 he was assigned Number 199 and transferred to the 6th (North Strand) Company based at Transport Union Branch Headquarters at 61 Ballybough Road.

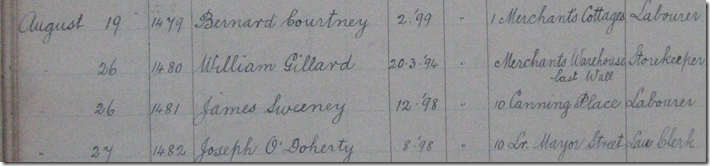

Bernard Courtney was born at No. 9 Tighes Cottages on 21st February 1899. He first attended St. Laurence O’Toole’s school and in August 1907 moved to The Wharf School, East Wall Road. (His registration details list fathers’ occupation as Labourer). He was a pupil here during the school boys strike in September 1911, which was inspired by the railway and related sympathetic strikes occurring locally at this time. Possibly through the influence of his schoolmates Bernard joined the Irish Volunteers in February 1916, but on April 24th, the day the Easter Rising began he initially set out with the Citizen Army. According to The Catholic Bulletin of February 1918 Bernard was distraught when the demobilising order was brought to the Courtney home on Easter Sunday. When orders came for his father to go to Liberty Hall the following day Bernard demanded to accompany him and fight with the Citizen Army. He was assigned to Jacobs Factory on Aungiers Street commanded by Thomas McDonagh.

Daniel first participation in the Rising was at the symbolic taking of the GPO.Later that day he found himself part of a group of reinforcements sent to Annesley Bridge to secure the supply lines from nearby Fr. Mathew Park, the main arms depot of the North Dublin Companies of the Irish Volunteers. Arriving about 4.15pm Daniel’s group quickly applied themselves to setting up barricades and roadblocks across the bridge. A reporter from the Irish Times sent to see what was happening promptly became their first prisoner – briefly arrested as a spy. The Times had never been kind to the ICA.

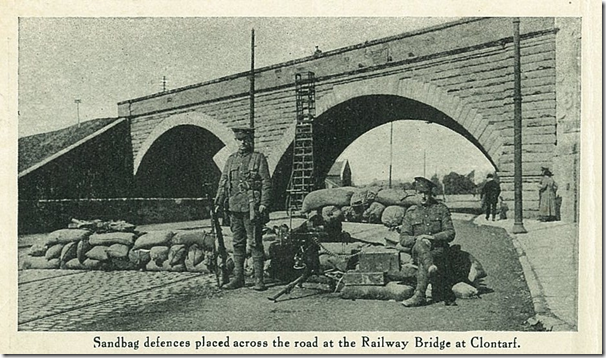

In September 1914 the War Office had commandeered the Royal Dublin golf club at Bull Island to be used as a musketry school. Word quickly came through that the soldiers from the school under Major Harold Fownes Somerville were approaching and the ICA party took up position in the Dublin and Wicklow Manure Company premises along the banks of the Tolka (now Ballybough House). It had been a late decision by James Connolly to occupy the Manure Works (The ITGWU had experienced real difficulties the previous year attempting to unionise the workforce). Volunteers at Staynes Corner (Annesley Bridge House) had launched an attack down Leinster Avenue and across construction sites (now Faith and Hope Avenue), scattering the Musketry School troops marching down Wharf (East Wall) Road. Panicked, they fled towards the protection of the railway embankment at least one of their number being killed by friendly fire and many were wounded. The Independent reported that the heaviest rifle firing “proceeded from the direction of Fairview” and “many fierce conflicts took place in the neighbourhood of the Wharf Road.”

The Volunteers had attempted and failed to blow up the railway embankment over the mudflats at what is now Fairview Park. This meant the British were able to bring up machine guns which raked the entire Annesley Bridge Road area. A report states that places two miles away from the scene saw bullets “now and again striking off the roofs of the houses“ and several window panes were shattered. Courtney and his colleagues at the Manure Works took the full force of their attack. One unfortunate volunteer who had climbed the Manure Works Chimney to act as a sniper was killed and remained suspended at his post for several days. At Annesley Bridge Road, a visiting Limerick-man named Moore was shot dead, having been seen behind the glass of the front door during a lull in the fighting.

Fearing that the garrison would be isolated the order was sent on Tuesday evening to evacuate to the GPO. Manpower was short and the Garrisons in O’Connell Street needed reinforcing. Ultimately the British took control of the port area and Somerville received a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his efforts, with both his captains being mentioned in dispatches.

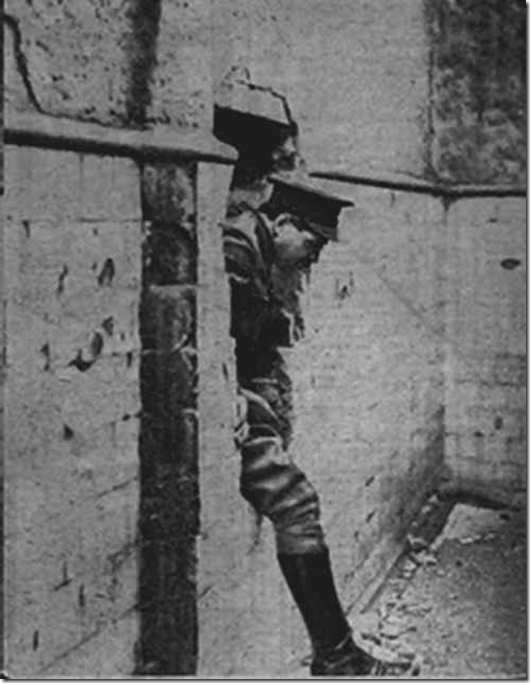

On arrival at the GPO, Courtney and former Caledon Road residents Peter and Walter Carpenter (Commander of the ICA Boys Corps) were sent to link up with Tom Leahy at the Metropole Hotel ( now Penny’s). Leahy, a shipyard riveter and future resident of Church Road, was a crack shot, and set Courtney and the boys to tunnel through the block towards Mansfield’s Shoe shop (now Eason’s) on the corner of Abbey Street. The British had taken most of the abandoned positions on the Eastern side of O’Connell Street and their snipers rained down on the Metropole Hotel. Leahy and ICA man Vincent Poole set about clearing the snipers so that Daniel and the boys could achieve their goal. Mansfield’s was eventually levelled by the British to facilitate an attack on the GPO but the small garrison held their own to the last until ordered to retreat to Moore Street via the GPO about 8.30pm on Friday. Daniel Courtney now found himself part of the famous dash down Henry Place towards Moore Street.

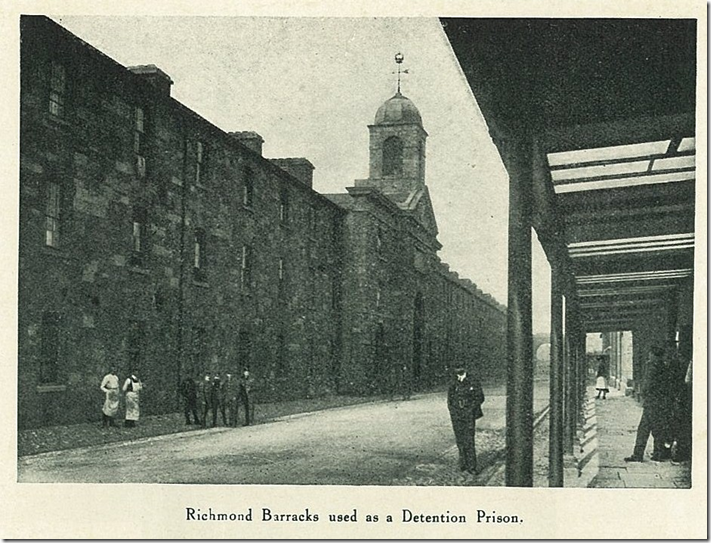

He would then take part in the intense effort to break through the walls and move through the entire street. On arrival at No. 10, Coogan’s Grocers; he was reunited with Tom Leahy, who was tasked with putting together a team to tunnel through the block to make an escape route to William and Woods chocolate factory for a final stand. Leahy, Courtney, and George King, with covering fire provided by Harry Boland, Oscar Traynor, Sean Russell, and Vincent Poole, worked themselves into exhaustion until they reached Miss Matassa’s Ice Cream Parlour at No. 25 at which point they collapsed. Awakening from their first proper sleep for several days they were given the news that their force was to surrender. Devastated at the news, Tom Leahy recorded that many chose to smash their precious rifles, bought with hard save pennies and sixpences, while others chose to bury them in the gardens of the Moore Street buildings. Some carried them out and then destroyed them before the eyes of their captors near the Parnell monument. Having been taken prisoner, Daniel was taken to Richmond Barracks from where he was transferred to Knutsford Prison in England on the 1st May. Later on he was sent to the prisoner of war camp at Frongoch in Wales which would become known as Irelands University of Revolution.

Jacobs had been quiet compared to the other garrisons in 1916. The Volunteers there saw little action other than bringing supplies or sending reinforcements to Stephens Green. Because of his youth Bernard was advised to leave but he refused. The main role of boys his age was acting as messenger to the other garrisons and it was said “he was the first to volunteers for any risky enterprise.” He appears to have been one of the volunteers sent to reinforce the College of Surgeons and appears as such on the ICA Roll of honour for that Garrison compiled in the 1930s. During the surrender negotiations he was persuaded to escape and made his way home safely to Bessborough Avenue. Soon after his health began to fail and was found to be suffering from Tuberculosis. By November he was sent to Crooksling Sanatorium near Brittas for treatment – one of the benefits available through his father’s membership of the ITGWU. Life was difficult for Julia Courtney in 1916. Her health had never been good and her eldest daughter, Catherine, had married in 1911 and moved away. With Bernard seriously ill and Daniel in Frongoch she faced destitution. The family moved to 90 Seville Place and The Irish National Aid Association, set up to help the families of those interned or killed in the Rebellion, came to her assistance with a weekly grant of £1.17.6. Daniel was amongst the last prisoners released from Frongoch, in December 1916. He returned home to find Bernard’s health deteriorating. He was moved to the Hospice for the Dying in Harold’s Cross where he died on 20th March 1917.

Only a short contemporary report of Bernard’s Funeral survives but it was one of the first spectacular events used to show that the Independence movement was alive and well. The Irish Independent stated “the deceased was a member of the Citizen Army which was well represented, as were the Irish Volunteers, Irish Pipers (without pipes), Cumann na mBan and kindred organizations.” A later description states that Volunteers carried the coffin to the hearse which then proceeded towards Glasnevin passing many of the locations such as the College of Surgeons which had been central to the 1916 Rebellion. The Last Post was sounded as he was lowered into the grave.

Daniel appears to have been blacklisted on the docks, only finding occasional days employment, though at the end of August 1917 the Irish National Aid Fund grant stopped, as he could support his family again. (The fund had provided a special grant in June towards the expenses of Bernard’s Funeral).

In 1917 the Transport Union was picking up the pieces caused by recent events. Thomas Foran, the acting president, was attempting to rebuild the organization on sound business lines and attempted to purge the union administration of those who couldn’t make the change such as P.T. Daly. This was seen as an attack on the old Larkin regime, if not an attempt on Big Jim himself, and the old guard decided to fight back. The Citizen Army fronted the attack causing uproar with some awkward questions from John Hanratty at the AGM in the Mansion House in December 1917. Nominations rather than elections were held and Daniel Courtney was nominated as a delegate to the No. 1 Branch by ICA men Owen Carton and John O’Reilly. The nomination was accepted but later turned over on the basis that Daniel was out of financial benefit. The ITGWU minutes for the period describe the episode as a disgrace. However they had passed a resolution earlier in the year wiping out 9 months arrears on men who had been interned due to the rebellion so it was a questionable decision. Courtney’s nomination was reinstated and together with Michael Connolly, whose daughter and four sons had fought in the rising and whose eldest son Sean was killed, went forward for the ballot on the 26 -28th January. Connolly represented the Port and Docks and had lost his job for his politics. He had been involved in the revival of the Women’s Workers Union and was then working at Liberty Hall. Both Courtney and Connolly were easily defeated, polling just 77 and 139 votes respectively. However soon accusations were flying that hundreds of votes had gone missing and was seen as another attempt to crush the Larkinites.

A war of words would erupt between the union factions. Accusations started spreading from the Larkinites that Foran, a member of the original ICA Council, who had regularly marched with them (pictured above), was alleged to have chosen the Fairyhouse Races rather than the GPO and James Connolly. Another story was that P.T. Daly, a favourite of the Larkinite faction and head of the Insurance Section, had been thrown out of the Irish Republican Brotherhood for embezzlement and had been denounced as a spy by James Connolly hours before the Rising. Courtney and Connolly may have failed to be elected to the Committee of the Union but among the Larkinites they were names to be reckoned with. Together with Mick Mullen they wrote to the newspapers. Mullen, from Abercorn Road, had been organizer of the agricultural labourers in North County Dublin and had served several terms in jail for union activities. Soon the letter pages exploded with accusations and counter accusations with even Sean O’Casey joining the debate. Courtney, Connolly, and Mullen were suspended and hired a lawyer to fight for re-instatement. The episode dragged on for several months until finally a court found in favour of the trio. But it had damaged the ITGWU and would eventually lead to the split and formation of the Workers Union of Ireland after Jim Larkin returned from America.

Other events were to intervene in Courtney’s life. Following meetings with Michael Collins and Cathal Brugha, the Citizen Army, then commanded by James O’Neill, agreed to provide intelligence and back-up to the volunteers. Bob DeCoeur, Chief Intelligence officer with the ICA moved to 48 Upper Sherriff Street and the Docklands was to play a significant role in the intelligence battle throughout the War of Independence. Troop movements were watched, as was the Auxiliary HQ on the quays, attacks were launched on black-listed goods, raids were made for arms shipments, and back up provided for Volunteer operation. Courtney played an active part and seems to have worked in conjunction with companies of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade. He took the Republican side in the Civil War until the untimely premature death of his wife Julia on 27th January 1923 brought his military career to an end.

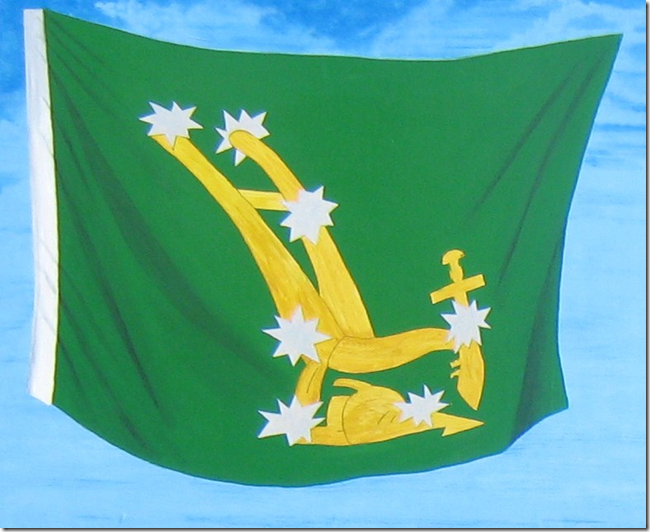

Courtney’s last major public outing was on Sunday 23rd October 1938 at Croke Park where veterans of the GPO Garrison were once again united for what is now a famous photograph. In keeping with the times, the session had to be delayed to accommodate a number of veterans then resident in the South Dublin Union. Throughout this period he was active with the Old Citizen’s Army Comrades Association and prominent in their annual Children’s Charity events at Christmas. Courtney had moved to No. 10 Upper Stephens Street within a stones throw of Dublin Castle where he died on the 24th August 1943. His funeral was one of the last major outings by the dwindling band of ICA veterans of the Rising. The honour guard included Walter Carpenter, Vincent, Christy, and Patrick Poole, James Joyce, Bill Oman, Joe Whelan, and Fred Henry. A delegation from the 1916 Veterans Associations was present as were veterans from the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade. True to the end his coffin was draped in the Starry Plough of the Irish Citizens Army and a firing party saluted him as the Last Post accompanied the lowering of the coffin. He was the oldest surviving member of the original ICA of 1913 and affectionately known as the Grandfather of the Citizen Army. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Hugo McGuinness

Sources for Images include: Tarlach O’Briain, Curtis Collection, East Wall History Group and Dublin City Libraries.(Union badge and Starry Plough from Merchants Road mural , painted by Arthur Kavanagh)

For comments, clarifications and/or further information contact: eastwallhistory@gmail.com