“…renowned specimens of horseflesh got their first lessons in Horseology.”

Joe O’Grady passed away in 1960, and it was in that year that ‘M.A.T.’ an Evening Mail Columnist recalled sipping a pint in the Wharf Tavern with him. Joe was a well-known poet, balladeer, and songwriter, and that evening he was lamenting his changing world. All the landmarks of Joe’s youth were vanishing. Places such as the Middle Arch, the Halfpenny Arch, Madge Mulligan’s Hut, even the Bathing Slip at what is now Alexandra Road, were just memories buried beneath progress. Sass Bollan, the genial headless horseman, hadn’t been seen on Johnny Cullen’s Hill since the 1940s triggering Joe to compose a timely lament. But what caused O’Grady the most regret was the demise of Nugent’s Field and the East Wall greats that once pounded its turf. This was a place where dreams were once made and nurtured and where many “renowned specimens of horseflesh (both draught and racing)” according to Joe, “got their first lessons in Horseology.” Joe knew them, because he’d helped “train” them, insofar as he and Fluther Good used to stack up haybales to teach the horses to jump over them. Among them were an extraordinary trio whom all Docklanders who’ve ever had a flutter on the Grand National should be genuinely proud of.

A British Lancer Regiment

The Nugent family were the last in a line of East Wall horse-breeders and dealers who up to the First World War stocked the cavalry regiments of Europe. Then in its aftermath, facing severe financial constraints, they concentrated on supplying the Sport of King’s, producing three extraordinary Grand National Champions between 1923 and 1931.

Cigarette Card showing Sergeant Murphy winning the 1923 Grand National.

First up in 1923 was Sergeant Murphy a 13 year old 100/6 outsider ridden by Captain Tuppy Bennet and owned by the American “Laddie” Sandford. Bred in Ireland by C.L. Walker, the Sergeant was put through his juvenile paces at East Wall’s Nugent’s Field until inevitably, he was sold on, eventually being bought by the young American undergraduate at Cambridge University who fancied a horse for chasing foxes with the local hunt. Sandford was unable to handle him, so he was sent back to the track and his impending place in history. The Sergeant had fallen at the Canal Turn at the 1922 National but got himself back up to finish fourth. Then teaming up with Tuppy Bennet he won the Scottish Grand National some weeks later. Sergeant Murphy won the 1923 race by three lengths with only six of the original starters finishing as it was run in a thick mist.

Ronald Reagan in the Sergeant Murphy Story

The win caused such a sensation that Hollywood came calling soon after and a movie was made based on the Sergeant’s life starring Ronald Reagan in 1938. The renowned Irish artist Sir William Orpen painted Sergeant Murphy’s portrait in celebration of this win. However , this story of triumph would not have a happy ending. Tuppy, unfortunately got a kick in the head in 1924 from which he died. Because of this all Jockey’s now wear helmets. Sergeant Murphy broke a leg in Scotland in 1924 bringing his racing career to an end.

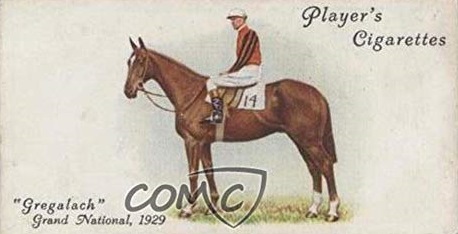

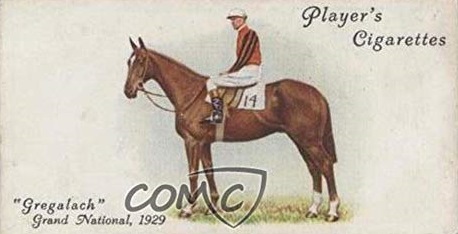

Cigarette Card showing Gregalach winner of the 1929 Grand National.

Next up in 1929 was Gregalach. The 1928 National had been won by 100/1 outsider Tipperary Tim the only horse to finish that year which offered hope for those looking for a jackpot from a complete outsider. Gregalach had fallen eight days previously at Sandown, making him, like Tim the year before, a 100/1 outsider and all the hopeful punters’ favourite for taking the bookies to the cleaners. Ridden by Bob Everett, Gregalach played it clever overtaking the favourite at the second last fence before winning by six lengths. 66 horses, the largest field on record, competed. Born in 1920, (a not insignificant year in Irish history) Gregalach went through his early paces in Nugent’s Field as machine guns riddled Dublin Port and gun battles along the Wharf Road were common. Perhaps it helped give him his edge.

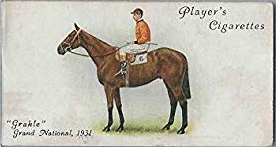

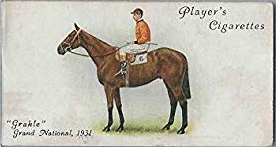

Cigarette Card showing Grackle winner of the 1931 Grand National.

Grakle’s win in 1931, ridden by Bob Lyall, so delighted his owner, the Liverpool Cotton Broker Cecil Taylor, that he gave a half-crown to every child in his local village. He could afford it as the prize-money was £9,310. Bob Lyall was only in the saddle as Grakle’s regular Jockey had injured himself some weeks before. He was Richard Pigott, father of Lester and Grandfather of Tracey. Grakle was a difficult horse to handle, tending to “pull” when in full flight, and would create a bit of history wearing a customised figure of eight noseband in the race which is still named after this wonder horse. It was his fifth attempt at the National and he set a new course record at Aintree at odds of 100/6 which would have made many of his hard-pressed old friends back in Dublin’s Docklands, such as Fluther Good and Joe O’Grady, very happy with the fortuitous windfall. Born during the Civil War year of 1922, like his fellow East Waller Gregalach, (who came second in the 1931 National), he may well have benefited from exposure to the munitions flying around East Wall and Fairview Park when he was only a nipper.

The Legendary Pat Taaffe.

Although only possessed of two legs rather than four, and something of a “Docklands blow-in”, an honourable mention has to go to the other legend of the turf, Pat Taaffe. Forever tied in song and story to his partnership with Arkle, (on whom he won three Cheltenham Gold Cups between 1964-66), Taaffe’s first serious berth on a horse came in Nugent’s Yard. Born in Rathcoole in 1930, Taaffe spent his holidays in East Wall and his love of the sport and skill in the saddle were first recognized and nurtured by the Nugents in their field off the old Wharf Road. Taaffe, of course, won the National in 1955 on Quare Times, a 100/9 outsider and again with the 15/1 Gay Trip in 1970. Despite all his success Taaffe never forgot where he got his start and was a significant fundraiser for the building of St. Joseph’s Church in the 1950s.

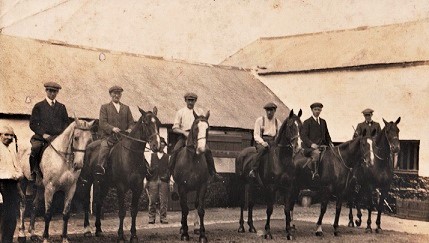

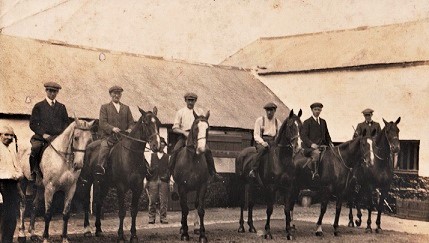

Stables at Nugent’s Field off Church Road.

Today there are few markers of the once great local Docklands industry of horse breeding and training which went back to the eighteenth century, when in 1756, Mrs. Brown announced that the Bay Arab would cover mares at Cook’s stables for 5 guineas and a crown each (about €1,500 today). Financial constraints brought on by the First World War and the Irish Revolution forced the Nugent’s to sell much of their field of dreams for a factory in the 1930s. The same constraints had earlier required the sale of Ledbury, Linden, Pistachio, and Sans Pensee to the Brazilians in 1915. They had little financial gain from the wins of Sergeant Murphy, Gregalach, or Grakle, as their role was to bring the horses to a stage where they were competitive and would fetch a good price with the honour and glory going elsewhere usually in a different country. Grakle was sold for 4000 guineas and Gregalach for 5000 guineas to the owners who would ultimately gain glory with them. The Nugent’s would have originally sold them for a fraction of that. But people in the Docklands knew where these great horses came from and for the likes of Joe O’Grady it was something to celebrate.

The refurbished Seaview House

Today Nugent’s Field lies beneath a number of Apartment complexes. The only horses to be seen in the area are Anto Kelly’s and then they are usually attached to a vintage hearse or one of the thirty or so carriages which form his nostalgic fleet. But Seaview House, built by the Bollans, and lived in by those other great horse-people, the Shiels and the Nugents, still remains and has recently been refurbished to its former glory.

Recalling it from her childhood, Lucy Brennan (nee Nugent) remembered it as “a solid, sprawling house, which in its heyday had three street entries. A high whitewashed wall with a red, latched door in it gave downwards onto a steep cement stairway, at the bottom of which were a rectangle of grass, about four stables and a plain backdoor into the back-kitchen-cum-scullery. There would have been fields behind, where the horses grazed when there were horses: but they had been replaced by houses and industry.” Horse-training may have declined in Lucy’s day, but a somewhat older Joe O’Grady, known to her by the nickname of Pudner, drove a milk cart for a local Dairy and kept his horse at the stables behind Seaview House and occasionally allowed Lucy accompany him as he delivered milk in East Wall and the Docklands.

Beside Seaview House, the pillars of the gateway through which Fluther Good led the likes of Grackle and Sergeant Murphy in and out of Nugent’s Field are still standing and provides a tentative link with a once glorious past through which a small part of the Aintree Grand National will always be linked with the Dublin Docklands.

Corrections , clarifications and further information welcome

eastwallhistory@gmail.com