John Joseph (‘Sean’) Conroy

John Joseph Conroy was barely 40 years old when he died from Tubercolosis on 15th January 1937. A past pupil of both St Laurence O’Tooles on Seville Place and the Wharf Boys School in East Wall, he had served time as an apprentice at the Dublin Dockyard Company. As a boy he had joined the Fianna , and during the revolutionary period he was a volunteer with the Irish Citizen Army, the Irish Republican Army and the Republican Police , and afterwards joined the National Army. In defiance of the effects of a gun-shot injury he showed great courage during the Easter Rising, saving the life of a comrade under fire and was afterwards imprisoned in England and Wales. He enthusiastically participated in the war of Independence until the treaty. Despite his years of membership of the Citizen Army and his obvious bravery and determination during the struggle his funeral was not attended by ICA veterans or survivors of the St Stephens Green Garrison. This is his story :

Faithful Place , Tyrone Street

The Conroy’s were just another one of the migratory tribe of workers who populated Dublin’s North Inner City in the late 19th century. Their fortunes centered around John Conroy’s employment prospects and their constant mobility is traced in the births and deaths of their young children. They lived at a number of addresses along Tyrone Street, John Joseph being born at a lodging house at No. 40 on the 8th February 1896. They later passed through Montgomery Street before arriving at Julia Conroy’s father’s address at 3 Ralph Place, off Oriel Street in the North Dock, at the turn of the century. They are recorded here in the 1901 census, eight of them occupying two rooms of the small tenement cottage. The third room was occupied by the eight members of the Smullen family.

School register entry , Wharf School .

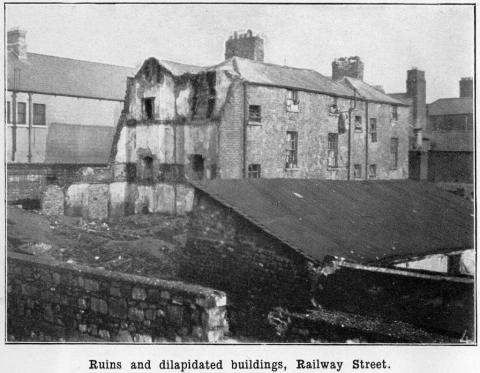

The Conroys were still living in Ralph Place in August 1905 when John Joseph transferred to the Wharf School from St Laurence O’Toole’s. John Senior was working as a Blacksmith’s Helper at the Dockyard but by 1911 they were on the move again, this time to a tenement at No. 2 Buckingham Place. John Conroy was unemployed by this time and of the nine children born since his marriage to Julia Kane in 1889 only three survived. By then John Joseph had joined the Fianna a nationalist organization founded in 1909 to counteract the influence of the British Boyscout movement set up by Baden Powell. The family had moved once again this time to 40 Railway Street which would be their most constant address for many years.

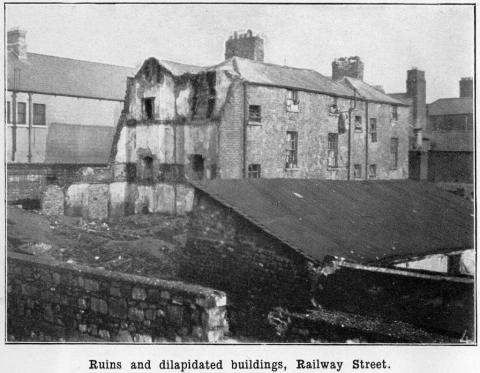

The 1914 Housing enquiry found that 25 of the houses on Railway Street were in ruins with a number of open spaces where buildings had either being demolished or fallen down. However the rent was cheap and in the battle for survival which encompassed daily living in Dublin’s Northside tenements this was important. That same year the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin claimed Railway Street was at the center of a triangle of the worst poverty in the city. Here the Saint Vincent DePaul, through Our Lady of Lourdes Breakfast Committee , instigated free Sunday breakfasts to counteract the free breakfasts already on offer from proselytizing protestant competitors. The Archbishop described this as “a revolting crime against conscience being carried on in the name of Christian charity.” By December they could claim that those attending their competitiors had fallen from 800 to 80 “keeping the alluring bait of the proselytizers from endangering the faith of destitute Catholics.” For the destitute, and there were many, breakfast was breakfast whatever it’s religion.

Chrissie Hawkins who grew up in Railway Street recalled it as a tight knit community where people looked after each other. Nobody had any money so they couldn’t help with the rent but for anything else people gave what they had. Survival on the street centered around the pawnshop on Corporation Street on Monday and then you redeemed the goods pawned on Saturday. It was part of the notorious Monto Red Lights district and Hawkins remembered the larger houses on the street being brothels “full of country girls, lovely girls .. an awful lot of them” and “if you were short of anything they would give money to you.” The girls seem to have been particularly helpful when someone died organizing collections for funerals and burials. Timmy “Duckleg” Kirwan remembered it for it’s numerous Sheebeens and Speakeasies with hundreds of these illicit shops in the area, the owners keeping the drink in manholes until required and often the shops doubled as brothels. For children there was money to be made doing messages while their mothers made an extra few shillings cleaning and washing up. Families were large, Chrissie Hawkins remembering one of 24 children, but most died young from the numerous diseases which regularly permeated the district. For many of the owners and landlords of such properties it financed a respectable future in places such as Scotland or Canada but for the ordinary residents it was a part of the daily struggle for survival.

By the time of the Great Lockout in 1913 John Conroy was working as an Apprentice Plater at the Dublin Dockyard. Co-workers included Willie Halpin, Shop Stewart with the United Society of Boilermakers and Shipbuilders and member of the Irish Citizen Army. Halpin was from Hawthorn Terrace in East Wall and like Conroy had also joined the Fianna before transferring his allegiance to the ICA. His father Edwin had run a progressive school at the turn of the century in East Wall, and it is probable that Halpin passed on his idealistic socialism to young apprentices at the dockyard such as Conroy and John Joseph Geoghegan. Other colleagues in the shipyard included Ellet Elmes, Peter Carpenter, Tom Leahy, and the Connolly brothers George, Matt, and Joe. All had strong socialist leanings, would serve in the ICA (although Leahy initially joined the Volunteers) and all participated in the 1916 Rising.

John Smellie, who ran the Dublin Dockyard, was an enlightened employer and as Dublin employers went was very fair in his treatment of his workers. As a Controlled Establishment through the period of the First World War, labour problems were dealt with by Ministry of Munitions Tribunals . Smellie regularly intervened in disputes offering compromises so his workers would avoid harsh financial penalties. But it was a hot bed of radicalism and John Joseph or “Sean” Conroy, as he was then known, was right in the thick of it.

Conroy had joined the Irish Citizen Army in 1913 and was an enthusiastic volunteer. The ICA had acquired a number of old shotguns with hair triggers which were almost as dangerous to themselves as to any opponents. Conroy was at drill practice at Liberty Hall on the evening of the 4th March 1916. Standing too Conroy was talking with John Hanratty, with Richard McCormick and Frank Robbins, nearby. Liberty Hall was packed as Sean McGlynn, an engineer with G Company, 4th Battalion of the Irish Volunteers had been delivering a lecture on the use of explosives. McGlynn worked as a plasterer and was then on strike and making the most of the opportunity to share his knowledge and skills. As part of his lecture his pockets were filled with sticks of dynamite. They failed to notice a new recruit pick up one of those double barrel shotguns and take aim. Not realising it was loaded he fired hitting Hanratty in the elbow and legs and Conroy in the shoulder narrowly missing McGlynn and the deadly contents in his pockets. If it had then the Rising might have had to be deferred if not put off indefinitely. Kathleen Lynn was holding medical classes in Liberty Hall that evening and immediately rushed to see what had happened. Her quick intervention saved Conroy greater complications but for Hanratty the 1916 Rising was over before it had begun. He would spend several months recovering.

Irish Citizen Army , roof of Liberty Hall

The shot had ripped away a large part of the muscle tissue of Conroy’s Left shoulder. Kathleen Lynn treated him at home in Railway Street and undertook 10 separate grafts of muscle tissue to replace the flesh lost to the shotgun blast at her house in Belgrave Square. Conroy recovered but would continue to have trouble with the arm. Despite his ailments it’s probably a sign of Conroy’s commitment that he mobilized on Monday 24th April 1916 for Liberty Hall. Nobody would have condemned him if he had stayed at home due to his injury. When the DMP investigated his case they found that neighbors had noticed that he had left 40 Railway Street in his ICA Uniform that morning. That fact alone almost certainly prolonged his detention after the Rising.

It was probably because of his ongoing problems with his arm that Conroy was among those assigned to guard Liberty Hall while the final supplies were transferred to the GPO. Conroy was then sent by James Connolly to Stephen’s Green where he fought with difficulty due to his inability to shoulder a rifle properly without considerable pain. He was posted in the Green with Francis O’Brien, an old East Wall colleague from his Fianna days , now with E Company, 2nd Battalion. On Monday evening he was there when O’Brien was shot six times in the neck, shoulder, back, and left side. Without panicking and with some difficulty, Conroy managed to drag O’Brien to nearby St. Vincent’s Hospital which not only saved O’Brien’s life, (he underwent treatment for two months) but ultimately ensured that O’Brien evaded being arrested. Conroy then took part in the evacuation to the College of Surgeons and was placed on guard at the door of the college with Johnny McDonnell for the rest of the week. Although escape would have been easy from here he remained to be arrested during the garrisons surrender on the Sunday.

Conroy was initially held at Richmond Barracks until transferred to Stafford Jail in England on the 1st May 1916. Two days later he was sent to Frongoch the prisoner detention camp in Wales. The DMP placed Conroy in the C category of prisoner, which was minor, but the fact that he left Railway Street in uniform meant he wasn’t released until December 1916. Little is known of his time there but it’s believed that he developed the respiratory problems which would eventually kill him while in Frongoch his obituary stating “his health had been impaired from the time of his internment.” The regime at the Welsh detentions camp was tough. One time Caledon Road resident, Peter Carpenter, while praising his treatment in English Jails, had a simple description for the guards at the Welsh location. “Bastards!” Irish MPs regularly questioned the treatment of prisoners during Parliamentary Debates at Westminster and on one occasion the Camp Commandant was compared with Captain Bowen Colthurst (who murdered Francis Sheehy Skeffington) with an accusation being made that the Commandant was completely mad.

On return to Dublin Conroy was taken back as an apprentice at the Dublin Dockyard. He had rejoined the ICA and once more began to have treatment under the care of Kathleen Lynn who continued to perform the series of grafts needed to build up the missing muscle tissue in his arm. However as the problems continued his apprenticeship was lost as he was unable to swing a hammer in any useful way.Things were moving slowly at the ICA and he seems to have grown close to two others apprentices, Martin and Michael Kelly, who worked with him. Conroy would later marry their sister Emily in 1925. The brothers were both members of C Company, 2nd Battalion IRA, and in 1921 Conroy applied for and was granted a transfer from the ICA to their unit.

Auxillaries at Amiens Street

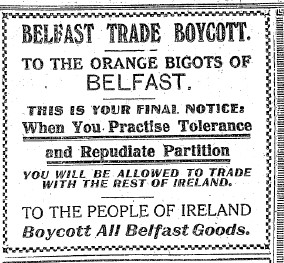

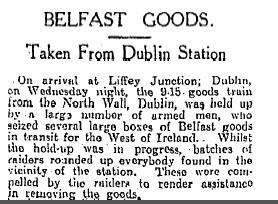

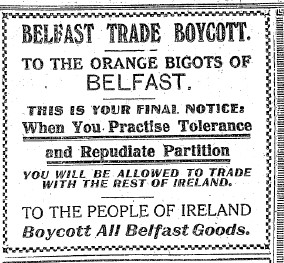

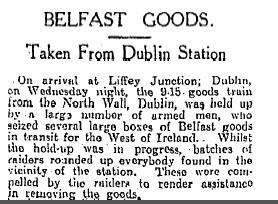

The moved to C Company, then under command of Sean Lemass, saw him immediately into action. Shortly before curfew on Tuesday 5th April 1921 he was part of a team which attacked a Crossley Tender coming down Talbot Street towards Gardiner Street by throwing a handgrenade towards it. Conroy was armed with a Webley pistol but had no chance to use it as they had run away from the scene almost as soon as the grenade exploded. Little damage was caused and the British soldiers immediately began raiding nearby houses. However it was exactly the type of start Conroy was hoping for and more was to come two weeks later. On the evening of the 19th April Conroy was one of a three man team including Frank Cotter and Gerard Murray which held up the 8.30 Belfast Train carrying a cargo of tobacco. The Dail had instituted a nationwide boycott of Belfast goods and throughout the country attacks on trains and warehouses were common and the goods destroyed. It was something of a speciality of the Citizen Army so they were encroaching on their territory. However, the attack and subsequent dumping of the tobacco in Spencer Dock near the junction with the Liffey was quite audacious, particularly as it was five minutes from the London and North Western Railway Hotel then in use as a headquarters by the Auxiliaries.

After the initial excitement Conroy had few opportunities to engage in action, C Company’s activities largely centering on patrols in their area around Talbot Street. Conroy attended training camps in places such as Kilmore and Santry which on one notable occasion included members of the Active Service Unit. His cousin Herbert Conroy, a member of the first Squad who carried out the Bloody Sunday attacks on British Intelligence, was heading up A Company of the Irish Republican Police .Once again Conroy sought and was given a transfer, enabling him to join up with his cousin. Again he saw little direct action, the IRP’s duties in Dublin largely consisting of patrolling the streets, imposing curfews, and implementing directives from the Dail. Much of his time was taken up with training at the Clann na hEireann Hall at Fairview and twice weekly drills at Marino. On the day of the attack on the Custom House, Conroy’s role with the IRP saw him engaged in patrolling the nearby streets away from the main action.

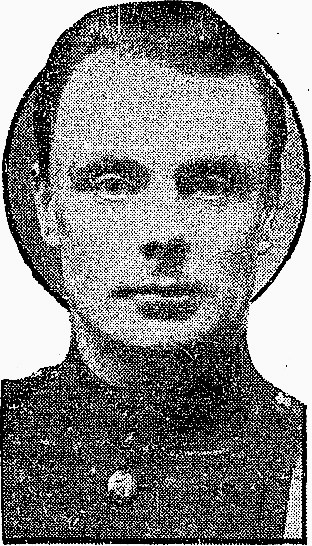

Herbert Conroy , Republican Police

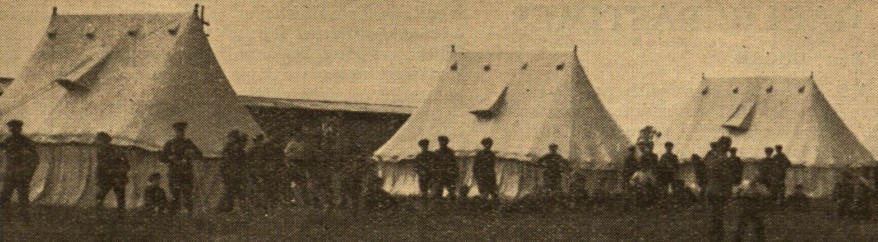

National Army , at Beggars Bush

With the advent of the Treaty Conroy joined the National Army signing his papers at Beggars Bush Barracks on the 8th March 1922. After seeing service at Portobello Barracks and at Kilkenny, Conroy was posted to Gormanston Camp then being used as a detention center for over 1000 anti-treaty prisoners. The ICA had overwhelmingly taken the anti-treaty side and although Conroy was serving with D Company, The Machine Gun Corps of the 37th Battalion, he must have regularly encountered the dozen or so of his former colleagues then imprisoned at the camp. Ultimately his problems with his arm caught up with him and he was invalided out of the army on 28th July 1923 as medically unfit having served for just over one year.

Gormanston Camp 1923

Conroy applied for a wound gratuity under the 1923 Army pensions Act and after a rigorous series of examinations was turned down. While the board accepted that he had lost power in his left shoulder and hand-grip it was not deemed serious enough to grant him an award. Interestingly Kathleen Lynn was the only member of the ICA to support his application and that was to acknowledge the medical treatment she had undertaken following the accident at Liberty Hall. Conroy again applied under the amended act of 1925 for a military service pension and this time he was more successful receiving a pension of £45.15 shillings per year or less than £1 per week. Again only one colleague from his ICA days gave him references that being Patrick Lawlor who like Conroy had joined the National Army and was at that time a Lieutenant based at Limerick. Unable to work at his trade he faced long periods of unemployment and following his marriage in 1925 he emigrated to the USA living at a succession of addresses in New York between 1929 and 1932. Experiencing continued problems with getting his pension sent to the right address Conroy returned to Ireland that year and worked as a house painter while he attempted to settle his affairs. With failing health things seem to have been difficult Conroy attempting to get an advance on his pension in 1936 presumably to pay the fare back to the United States. John Conroy died of TB on the 15th January 1937 at 26 Carleton Road the house of his wife’s parents.

Conroy’s funeral was large with a strong military presence at Saint Vincent’s Church on Griffith Avenue and at Glasnevin Cemetery. Numerous members of C Company, 2nd Battalion who had joined the National Army were there, as were many then serving members of the armed forces. In a sad reflection of the divide caused by the Civil War not a single former member of the Irish Citizen Army or representatives of either the Old ICA or Stephen’s Green Garrison were present. The only connection to his former comrades was the presence of the wife of Sean Connolly (killed at the City Hall in 1916), who was a relative of Conroy’s wife.

Daring Raid Conroy participated in .

For clarifications, corrections or further information please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com