“The first high-explosive shell of the long promised second battle of Clontarf has landed on the East Wall Road and blown an Irish firm out of existence and 300 Irish workers out of employment …”

It was a building many associated with industry in the area – some remember it was Wiggins Teape , older residents recall it as Fry-Cadburys . It’s demolition in controversial circumstances in 2001 is still a sore subject for many locals . It was originally known as Virginia House , and this is the fascinating story of it’s early days , one which was tied up with the political turmoil of the day.

On February 16th 1932 Eamonn DeValera led the recently formed Fianna Fail party into government and would retain power for most of the remaining decade. As Charles Dicken’s once put it “it was the best of times, and it was the worst of times,” depending on your perspective and location. Kathleen Behan, then living at 18 Russell Street off the North Circular Road, recalled it as an era of supping “sorrow out of a long spoon.” For her family it was a time of soup kitchens and visits to the pawnshop, with dole queues four deep and winding around the corner from the dole-office on Gardiner Street. She recalled on one occasion, cooking a pincushion stuffed with oatmeal as she had no other food available.

The Eucharistic Congress arrived in Dublin from the 22-26th June 1932 to celebrate the 1700th anniversary of the coming of St. Patrick to Ireland and a rapidly growing Dublin Port soon found itself the location of numerous “floating Hotels” as Harbourmaster John Henry Webb brilliantly improvised in the Docklands area to accommodate Dublin’s lack of tourist bed-spaces. Over a million people attended the closing mass in the Phoenix Park tantalizingly suggesting the potential of a buoyant future Tourist Industry. However, by the end of the month DeValera had Ireland engulfed in an economic war with Britain which depending on what you were engaged in meant a probable boom or bust. For residents in the Docklands this would have mixed results.

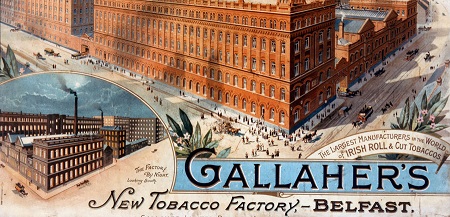

Derryman Tom Gallaher began his career hand-rolling tobacco and selling it from a cart. However, after his move to Belfast, his astute business acumen, would see his company rise to being one of the largest Tobacco producers in Europe and his factory, (spread across seven acres on York Street), was the largest of its kind in the world employing 3000 people by 1907. Twenty years later they were producing 40,000 cigarettes per minute with their Park Drive brand becoming one of the markets leaders. The company opened factories at London and owned tobacco plantations at Virginia in the USA. They were also among the largest buyers of raw tobacco on the global market. In 1908 Gallaher bought the site of the recently bankrupted Dublin Distillery on Pearse Street for £20,000. Interviewed by the Irish Times after the auction he refused to comment on whether he intended producing tobacco products at the location or retain it as an investment. They would quickly develop an unassailable position in the southern Irish Cigarette market and a sizable part of the sales in pipe tobacco and snuff as they developed what an Ulster writer would call “an enormous vogue during the heydays of the Irish Revival movement.”

Gallaher was an enlightened employer, being one of the first in Belfast to reduce the working week from 57 to 47 hours and introduced annual paid holidays. His factory served hot meals at cost price to their staff at lunchtimes and he seems to have been held in high regard by all those who worked for him being described as “courteous, kind, and generous.” He was noteworthy for refusing to bow to sectarian pressure to replace his Catholic workers during tensions in Belfast. However, he could be tough and inflexible when required particularly with Trade Unions as Jim Larkin would learn to his costs during the 1907 Belfast Dock Strike. When Tom Gallaher died in 1927, he left a personal fortune of over £500,000 or about 25 million in today’s money. Lacking a male heir, the role of leading the company fell to his nephew, John Gallaher Michaels, (known as J.G.), who had been manager of the company’s American operations.

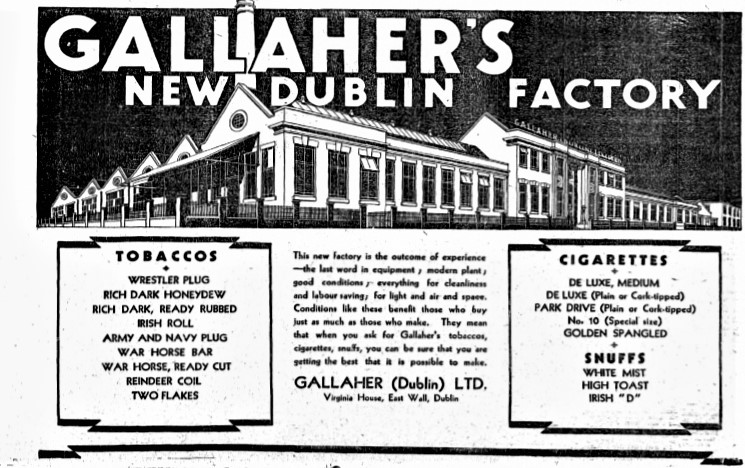

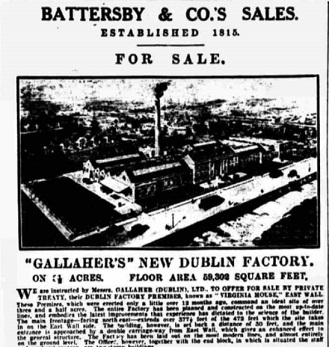

Like his uncle, Michaels lacked a male heir, but it still took people by surprise when he decided to sell all the share capital in Gallaher’s to Constructive Finance & Investment for several million pounds who in turn offered the shares to the public on the open market in 1929. Michaels was struck down with pneumonia in October that year so it may have focused him on his imminent mortality. He would suffer indifferent health up to his death in 1948. That same year Michaels began negotiations with the Saorstat Government regarding the opening of a factory in Dublin. As rumours began to spread it was assumed that Gallaher’s would acquire the recently closed Goodbody’s Tobacco Factory off the South Circular Road. The company had been in business almost 100 years and fell into voluntary liquidation in 1929 with 250 mostly female workers losing their jobs. When the announcement finally came it was that the factory was to be located on a green field site consisting of three and a half acres at the junction of Church Road and East Wall Road. These were badly needed jobs and the factory would, as one writer put it, “form no mean acquisition to a city with a merited pride in its leading buildings.”

The location would probably have been familiar to the management of Gallagher’s. During the recent War of Independence (and subsequent partitioning of the country) Gallaher’s had featured prominently in local attacks during the Belfast Boycott campaign of 1920-21. The Dublin Docklands area had a strong Socialist and Republican tradition , and the local Irish Citizen Army carried out numerous operations which saw boycotted produce , including Gallaher’s end up either in Spencer Dock or the Royal Canal at Charleville Mall. Similarly, the Dublin Brigade of the IRA intimidated local shops such as the Bayview Stores on the North Strand Road, while a Belfast Sales Rep was tarred and feathered and chained to the only public railings in the area at the Ivy Church.One report claims that in September 1921 shots were fired in the direction girls on their way into work at a Gallagher’s premises although nobody was injured. There were similar incidents throughout the country. At the time Gallagher’s virtually dominated the Cigarette market in the southern and western counties which would eventually become the Saorstat or Irish Free State. Ultimately, they were driven from this market. However, they fared somewhat better than their fellow Belfast manufacturers, Murrays, producers of renowned tobaccos such as Erinmore and Yachtsman’s Navy Cut, who had their premises on Talbot Street burnt to the ground in an arson attack.

Despite this Tom Gallaher had always prided himself on retaining the Independence of his company from the global conglomerates such as Imperial Tobacco Trust or The American Tobacco Corporation and took delight in featuring the Irishness of his products in their advertising. The above picture is just one example of the type of comely maidens which adorned Gallaher’s advertisements (and would no doubt have delighted Eamonn DeVelera). Despite being in a different jurisdiction after partition Tom Gallaher took a great interest in the industry on both sides of the Irish Border and was an enthusiastic supporter of attempts to grow native tobacco. In 1906 he purchased the entire crop grown at an experimental farm pioneered by Senator Nugent T. Everard at Randalstown County Meath. By 1930 this had expanded through several counties with one enterprising Roman Catholic Priest starting a co-operative cigarette factory using locally grown tobacco at Wexford. In 1923 the politician and diplomat Patrick McArtan had worked on a plan with Tom Gallagher and Irish American financiers to save the native Irish Tobacco industry in the Saorstat from what he perceived as a potential takeover by the Imperial Tobacco Trust. Indifference among members of the Cumann na nGaedheal government ultimately made it impossible and shortly afterwards Imperial Tobacco began to establish a significant presence in the market leading to seven long established Irish companies such as Goodbody’s failing between 1924 and 1930.

The site of Gallaher’s new factory had been part of the lands belonging to the Nugent horse-dealing family. James Nugent had been a substantial supplier of cavalry horses throughout Europe. Following the outbreak of WW1, he felt honour bound to refused to condemn his former clients in the German army, (despite being no longer able to deal with them because of the war), while engaged in a sales meeting with their British counterparts. Appalled the British withdrew from negotiations and Nugent effectively lost the most lucrative part of his business at a time when it was about to boom. By 1922 he needed finance and so borrowed £2,500 from the National Irish Bank placing the land as security. Unable to discharge the debt the Receiver took it over in 1923, leasing a number of plots, and ultimately selling a section to Gallahher’s in 1929. This enabled Nugent’s son Bernard to discharge the family debt. They would then reinvent themselves as trainers in the horse racing industry and play a leading role in developing legendary jockey Pat Taffe.

By any standards this was exactly the type of flagship project that the embryonic Saorstat needed as a confidence building measure. Lever Brothers had led the way with their redevelopment of the old Barrington’s and Dublin Glass Bottle Company site at Castleforbes Works on Upper Sheriff Street. In 1930 Dublin Port announced an extensive land reclamation programme around Alexandra Road. Ship tonnage passing through the port had more than doubled between 1929-30 while the Port had spent £40,000 on new storage areas for tobacco. However, these advances had to be balanced against some of the new state’s largest employers such as Jacobs who had established their Aintree subsidiary as an independent company in 1922 and were now spread over 30 acres at Liverpool. By 1932 they were employing 3000 people over there and warning that any new tariffs on their products would lead to production moving from Dublin to Aintree. In 1933 Guinness began the construction of their Park Royal Brewery near London. They had temporarily moved their HQ there during the treaty negotiations of 1922. The loss of either of these companies to the state, both of whom were significant employers, would have been devastating. Meanwhile long established businesses and large employers such as the Anchor Brewery began to fail or close.

Against this background the announcement by Gallaher’s was to be welcomed . “In these days when the decline of Industry is almost the despair of the Statesman and the Economist and when retrenchment rather than expansion is in keeping with the times, the stimulus of a tonic is afforded by the contemplation of such a magnificent new factory as that just erected by Messrs Gallaher (Dublin) Limited in the Irish Free State Capital” was one writer’s comment on viewing the new building.

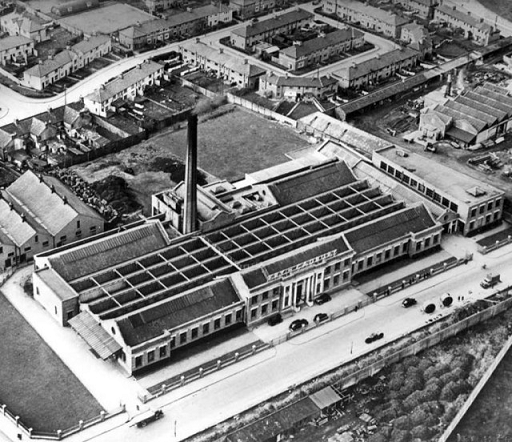

Designed by John Stevenson of Samuel Stevenson & Sons Architects of Belfast, this was conceived as a landmark development which would create confidence in the new state. The main entrance was on East Wall Road extending 377 ½ feet along the 472ft wide site and set 30ft back from the roadway, enclosed by pretty wrought iron railings by J. C. McGloughlin of Pearse Street. The facing of the entire building was in attractive Dolphins Barn brick, and the overall construction, largely using steel frames and reinforced concrete, was built by M’Laughlin & Harvey Contractors of Dublin. In fact, wherever possible, local companies had been used as either suppliers or contractors acting as a showcase of what the Building Industry in the Saorstat was capable of. Not surprisingly organizations such as the Engineering and Scientific Association of Ireland would organize for their members to inspect the project. The overall cost was £100,000.

The main entrance on East Wall Road was through a central revolving door leading into a spacious hall with a large teak horseshoe shaped reception desk. The elaborate polished-plaster walls were interspersed with black marble finished pillars with ionic caps. The passageways leading off this into various offices had black and white terrazzo floors leading to the claim that they offered “every facility for the efficient dispatch of business in the most pleasant and up-to-date conditions and where the atmosphere is such as to generate staff pride in their surroundings.”

The workers entrance was on the Church Road-side of the building as was the delivery area for stocks and supplies. The Timekeepers Office, Cloakroom, Leaf Sample Room and Laboratory, Stockrooms, Wages Office, and Gatekeepers apartments were all located here. Behind these were the Boiler House, Pump Rooms, Air Conditioning Plant, and Snuff Department. The Air Conditioning designed by The Aerozone Air Conditioning Company, was state of the art and not only kept the various tobacco products moist but supplied cool fresh air for workers throughout the building.

At the front to the right of the building was cigarette production with plug tobacco and other products being produced to the left. All were kept on a flat single story level for both efficiency and safety. Management offices and the staff canteen were in a two storey block just off the main factory to the right. A central glass roof over the main production area filled it with an abundance of light making the workplace “bright and cheerful.” Of particular note at the time was the advanced sprinkler system fed by two separate water supplies which would protect the factory from any potential fires.

Central to the production process was a German Machine, described as “one of the wonders” by a visitor on opening day. It could produce 2,200 cigarettes per minute or 132,000 per hour. As tobacco entered one end, paper in reels of two miles long enter at the other and as the paper had the brand logo printed the tobacco was formed into tubes, wrapped by the paper, and came out as a fully formed cigarette. The same witness was impressed by the “intelligence” of another machine which could count the cigarettes into tens, wrap them in tinfoil, slip in picture cards or coupons, and then deliver a finished product for the packaging department. “No human workers could compete with these robots,” he concluded. Like many companies Gallaher’s were using a gift coupon system to promote their products and this witness calculated that in an hour it could produce enough coupons to secure the ultimate prize of a motor car.

Building had been somewhat delayed through the Dublin Building Lockout of 1930-31 which also effected the developments of the new housing estates at nearby Marino and Donnycarney. Initially production was set up at a temporary factory on the Rathmines Road in April 1930. Gallagher’s noted this in their first advertisements when they apologised for delays in delivering their products since opening in February at East Wall “which for the moment we are unable to deal with.” However, they claimed they had had “an outstanding welcome” to the Saorstat market and the patronage they had received would “ensure the success of Dublin’s newest factory.” In his speech at the opening of the factory J. G. Michaels paid particular tribute to the, “competent, efficient and experienced” East Wall staff through whose efforts they had been able to open in just three weeks after the building’s handover and predicted that with their “help and loyalty” they would be just as happy as their colleagues in Belfast. He claimed Gallaher’s “worked with their workers and tried to make them feel that the management studied their interests from beginning to end. They were out to make the new factory one of the happiest in the Free State.”

When the factory opened 300 staff were employed, of whom around 200 were mostly adult women. 50 of these had previous experience having worked for Goodbody’s as did many of the Clerical and management staff. However, an Evening Herald reporter who visited the factory just before production commenced was told that this was only the beginning and that the project could eventually employ up to 600. While initially many of the key personnel had come down from Belfast to set up at Rathmines Road by the end of the first year of trading these had been replaced by local workers many promoted from the shop floor. Wages for the women were above the industrial average and by 1932 the company had begun to discuss the introduction of a productivity bonus in the future. However, when the ATGWU (Amalgamated , Transport & General Workers Union) applied for an increase for the male workers towards the end of 1931 they were told they would have to wait until the company was better established. In a show of how Gallaher’s treated their workforce on the 3rd April, 150 staff from the Belfast factory were taken to Dublin and after lunch and a tour of the city were brought to East Wall to showcase the new factory and meet the Dublin staff. Then in a novel idea, courtesy of Bohemians FC, both sets of workers headed to Dalymount park for a “challenge” match between teams from both factories.

Throughout 1931 Gallaher’s proceeded with one of the largest and most aggressive advertising campaigns which had ever been seen on the island of Ireland up to that date. Regular advertisements were placed in the National Daily and Sunday Newspapers while all the major city-based papers around the country were also targeted. It was at an unprecedented level at which none of their competition could compete. The largest local producer of tobacco products was P.J. Carroll of Dundalk who also offered a coupon scheme which you could collect and convert into luxury items. Gallaher’s had a similar scheme from day one but with that tantalising top prize of a motor car. Not surprisingly they would claim that their total investment in the Saorstat project by 1932 was £200,000.

Carroll’s factory in Dundalk was one of the Saorstat’s flagship companies and in 1930 was described as “the largest and most up to date cigarette factory in the Irish Free State.” From early beginnings in a humble, grocers shop it had grown into a substantial employer in the County Louth region. Much of their marketing success was down to their coupon scheme, available with Sweet Afton cigarettes which could be collected and exchanged for prizes. Where possible these were of Irish Manufacture thus showcasing the resources of the Saorstat. Numerous shops around the country contained window displays showing the luxury goods obtainable through the scheme. Gallagher’s not surprisingly copied the idea but offered extraordinary top prizes such as the motor car.

As early as 1923 Imperial Tobacco had begun to court the Cumann na nGaedheal government then in power. W.D. & H.O Wills opened a factory at Glasnevin in 1924 on the back of announcements the previous year by John Players and William Clark’s that they were looking for suitable sites for factories in Ireland. All of these companies were members of the Imperial Tobacco Trust. For J. J. Walsh, T.D. and Postmaster General in 1923, this was another attempt to “kill off the opposition” after which “the combine will retreat to their English base and exploit from there.” Walsh had little long term hope of large scale employment from the “foreign” tobacco industry. Despite this employment in the Industry had increased by over 1200 jobs between 1922 and 1930 largely due to the English companies creating an Irish operation. The failure of Goodbody’s seems to confirm Walsh’s prediction and then Imperial Tobacco, alarmed at the rise of Carroll’s share of the market, began to threaten customers with a withdrawal of their seller’s bonus unless they removed the Carroll’s displays from their windows. Imperial’s deal with retailers allowed for 50% of all available window space to be devoted to Imperial products however they were not prepared to give over the other half to the opposition. Few tobacco dealers could afford to give up their seller’s bonus, let alone popular Imperial Tobacco products, so that in February 1932 the magazine Honesty would report that only one location in Dublin still displayed Carroll’s gifts and that was the Restaurant of the Savoy Cinema. In January 1931 the magazine accused the then Minister for Industry and Commerce of standing by while Carroll’s were either put out of business or forced into the Imperial Tobacco family of companies.

There was much anticipation and speculation about Fianna Fail’s first Budget delivered on the 11th May 1932. As Labour TD William Norton commented it was in some degree a “Budget for the plain people” insofar as it made a “substantial advance” in the provision of housing and had a “note of sympathy for the unemployed.” However, for many TD’s this was a budget designed to lengthen the Dole queues. One of the most controversial taxes was on the new tobacco factories developed in the Saorstat post 1922 who would have a special tax of 7d per lb of tobacco used in their manufacturing. Effectively this would only apply to companies owned by multinationals from outside the Saorstat and give a distinct advantage to the old native firms. Part of the thinking behind this seems to have been influence by the actions of Imperial Tobacco against Carrols and Fianna Fail decided to take action to protect native tobacco companies. However, as one tobacconist writing as “snuff” would claim, Irish companies would be better off sending their sales staff round the country rather than getting protective duties from the government. He only stocked Imperial products as they were the only companies whose reps visited him. He had never had an Irish Company’s rep call at his shop.

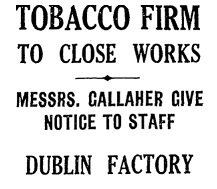

At the beginning of June 1932, J.G. Michaels issued a statement to the staff in East Wall.

“It is with the greatest regret that we have to inform all our employees that owing to the heavy losses sustained by us as a result of the differential duty rate imposed by the recent Budget it is now impossible for us to carry on our business. We have made every effort to secure equal treatment with our favoured competitors. But with no success.

We are, therefore, most regretfully compelled to give our employees one week’s notice expiring on the 8th June 1932, from which date they will be employed from day to day until our factory duty paid stocks are exhausted. Any employees finding other employment will be released on request.” Regarding the workforce Michael’s said that the situation was tragic, and in tribute to them stated that they had “at all times given us of their very best and have worked faithfully and well.”

During the 1907 Belfast Dock Strike, Tom Gallaher, who had played a crucial role in the development of Belfast Port, was threatened by James Larkin that he would spread a sympathy strike into Gallagher’s tobacco factory on York Road. Gallaher’s answer was that he would shut the factory down and move the entire production to London making the 3000 staff redundant. Larkin backed off. Faced with what he felt was a similar situation J.G. Michaels announced the imminent closure of Virginia House and the loss of all the recently created jobs. He wouldn’t be bullied or treated, as he saw it, unfairly.

It seems unlikely that Fianna Fail had contemplated the severity of Michaels’ reaction. Soon rumours began to be leaked to the press that they discriminated in the employment of workers on the grounds of religion which was emphatically denied by the East Wall Factory Staff. It was claimed that Fianna Fail supporters had offered jobs to 70 of the girls but there was no sign of them materialising. An English company was in negotiation to set up a car assembly plant on the site which never happened and would not have employed women anyway. Naively it was suggested that the factory be seized and run as a workers’ co-operative. Then suddenly stories appeared questioning exactly who were the real owners of the parent company Gallaher’s Tobacco Ltd. The local company had been registered in the Saorstat in 1929 but none of the key shareholders were residents. There had been a flurry of activity on the London Stock Market throughout 1932 and soon people were suggesting that there may have been more to the closure than the Saorstat’s new tariff on tobacco.

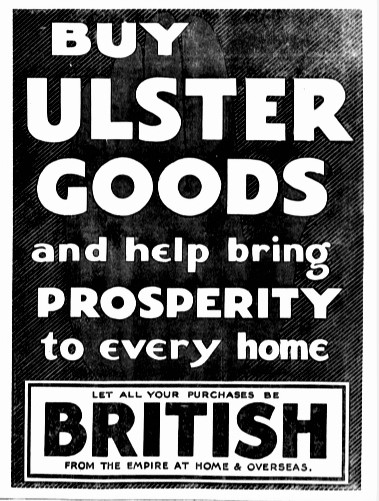

While it is difficult to say how much influence events in Ulster may have had it is interesting that an attempt was afoot to encourage Ulster citizens to Buy Ulster or Empire produced good which was directly aimed at imports from south of the border. This may have had some influence on Fianna Fail intransigence. The rumours of the senior company’s recent share sales also seemed to have impacted on many TDs. Behind the scenes the American Tobacco Corporation were attempting a hostile takeover bid and in order to counteract this, 51% of the shares in Gallagher’s were sold to Imperial Tobacco for one and a half million pounds.

At a special debate on the matter in the Dail, Richard Mulcahy of Cumann n nGaedheal had outlined Gallaher’s “Irishness” and pointed out that it was impossible for them to come into the Saorstat in 1922 or ’23 given recent history. He also pointed out that their annual Rates bill paid to Dublin Corporation was £700 in 1931. Fianna Fail had argued that the new tariff was actually below that paid by tobacco companies in Britain. Mulcahy demolished this argument demonstrating that only certain luxury types of tobacco paid more tax in Britain while most general types of tobacco, used in the more popular products, were below the new Irish rate.

As the Irish Women Workers Union represented the largest number of workers at the factory, Louie Bennett led a delegation to Belfast in August to negotiate with Michaels in the hope of saving the factory. The talks were inconclusive, but Gallaher’s agreed to hold off from selling the equipment and machinery at East Wall as she attempted to find a solution. Just before this another bombshell landed as Jacobs announced they were laying off 100 girls and moving those jobs to Aintree. Fianna Fail had also placed a tariff on materials used in confectionary.

From a socialist point of view, it was asked whether the Fianna Fail Government could really argue that Gallaher’s weren’t an Irish Company. Tom Gallagher had always seen himself as Irish (although not necessarily a Nationalist) and it was questioned whether Fianna Fail were now saying that Belfast was no longer an Irish city. The United Irishman newspaper argued that the party was re-enacting the War of Independence through its actions against what was generally seen as a model employer :

“The first high-explosive shell of the long promised second battle of Clontarf has landed on the East Wall Road and blown an Irish firm out of existence and 300 Irish workers out of employment. Mr. Lemass and Mr. McEntee, the blind gunners of Fianna Fail are quite pleased with the work of their heavy artillery. They care nothing what they hit so long as they destroy something. The wreckers of 1922 are still the wreckers in 1932.”

Writing in the trade union paper ,The Watchword, Louie Bennet, of the Irish Women Workers Union (IWWU) stated:

“It may eventually be possible to get the young girls absorbed in other industries, but the prospects for the older women are of the worst, especially for those who have been ten or more years in the industry. Mr, Lemass must surely understand the difficulty of training adults in a new industry, and the practical impossibility of adapting to new processes, workers who have spent years in the same occupation. If Gallagher’s factory goes the more senior employees will have to face a poverty-stricken future. The first casualties in Mr. Lemass’s war.”

Sean Lemass announced that the Government were working on getting alternative employment for the workforce although he couldn’t guarantee that it would be on the type of terms on which they had recently been employed.

[ For a lucky few, jobs would be had at the Cadbury’s Chocolate Factory when it opened on Ossory Road in 1933. Lever’s at the Castleforbes Works, with what was described as “the best jobs in the Docklands” were expanding, but they had a full workforce. The remaining local options for women were far from great. Goulding’s Fertilizer Company had a sack factory on Alexandra Road which employed women. The hours were long and the work back-breaking. Lil Fagan who worked at Goulding’s at a later period remembers it as a “great laugh” because of the camaraderie but they only employed about 12 girls. Lil had previously worked in another sack factory, Smiths on Common Street, with her friends Bluebell Murphy and Dinah Proctor where she “classed” the sacks. She developed TB which meant she constantly had chest problems so she only lasted 6 months in Goulding’s.

The East Wall Packing Company described by one staff member as one of the “Fianna Fail sweat packing factories” employed 52 girls at wages from 4s 9d up to 10s 3d per week packing various products by hand. Other girls were on piece work packing sachets of Epsom Salts at a rate of 2s 6d per ½ cwt (25kg) although this was reduced by 3d in 1934. Six girls were fired when they suggested joining the Irish Women Workers Union. ]

Bennet sought assistance from William Norton, the Labour Party leader in the Dail, whom she hoped might give raise the situation and be a voice of influence in parliament. Norton refused to meet her delegation as the WWUI were non-affiliated to the Labour Party. Gallaher’s had been emphatic- either the tariff went, or the Factory went. Running out of options Bennet achieved a type of deal during a meeting with Lemass. The government would give Gallaher’s an exemption, but Gallagher’s would have to sell 51% of the Irish Company to Investors living within the Saorstat so that it effectively became an “Irish” Irish company. The share sale was to be completed by 1st February 1933, however Lemass noted in Cabinet on the 5th September 1932 that finding the type of capital needed might not prove easy. Throughout the year Newspapers had commented how the wealthy and their capital were fleeing the Saorstat. Two weeks later it was announced that Red Abbey Tobacco in Cork had acquired much of the machinery from the East Wall Factory. A similar announcement heralded the remainder of the machines going to Donegal. The advertisements, first published in June, for the sale of the factory reappeared.

Both Gallaher’s factory and 300 good jobs were lost to East Wall. The company had operated for just eighteen months. Women’s employment just wasn’t a priority for political parties in 1932. In a final effort Bennet tried to extract an agreement from Lemass that the East Wall workforce would get first options on any jobs which became available if and when the factory was reopened under new ownership. She was told there were no jobs for them as companies wanted young inexperienced girls just entering the job market for the first time.

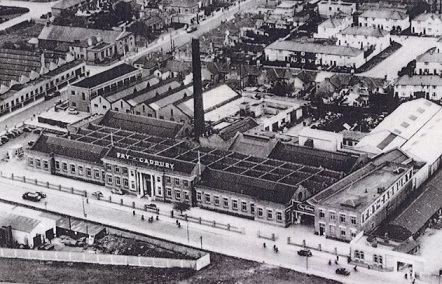

In 1939 Fry Cadbury’s were looking to expand and seeing an opportunity at the vacant Gallaher’s factory promptly moved from Ossory Road. Renamed Alexandra House, the chocolate factory would be one of many East Wallers favourite memories both as a great employer and for the quality of its products often brought home by parents and neighbours for lucky children. Local legend suggests that it’s proximity inspired local chip shop and Ice Cream parlour owners, the Andreucetti’s, to invent the 99 Ice Cream Cone or choc ice. Cadburys remained on the East Wall Road until the opening of their current factory in Coolock in 1964. During the redevelopment of the site a few years ago, Owen O’Flynn, one of those who worked on the building site recalls that the delightfully pungent smell of cocoa was still everywhere.

In 1932 Gallaher’s were the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer in Britain. In 1934 they acquired Peter Jacksons, followed by Robinsons in 1937. Over the subsequent years they would acquire J. Freeman & Sons in 1947, Cope Brothers in 1952, and the prestigious Benson & Hedges in 1955. The alliance with Imperial had been to stave off a hostile takeover bid by the American Tobacco Corporation. However, they retained their managerial independence as part of the deal. In 1963 Gallaher’s once more opened a factory in Ireland at Ayrton Road, Tallaght. Four years later they contacted the IWWU to discuss a new shift system which would facilitate young married women with families remaining in employment.

*********************************************************************************************************************************

This is part of our series of features on industries, premises and public houses in the North Docklands . If you have any material of interest – photos, documents , personal or family recollections then please get in touch .

Any corrections, clarifications or further information please contact us:

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

***********************************************************************************************************************************

Epilogue : By the end of the 1930s Kathleen Behan and her family were living in a house on one of the Saorstat’s new housing estates at Crumlin. Isolated and lacking any facilities, her son, the future writer Brendan, described it as being like arriving at Siberia.