From mascot to marksman – The story of William Halpin and the 1916 Rising

Easter Monday 1916 was a defining moment in Irish history. At noon of that day, a rebellion against British rule was launched in Dublin City, which was to set in motion a series of events that would shape the Island of Ireland throughout the 20th century and into the current age. On Easter Monday today, Joe Mooney of the East Wall History Group tells the story of William Halpin , an Eastwaller who was amongst those who marched out on that day to ” Break the connection with England“.

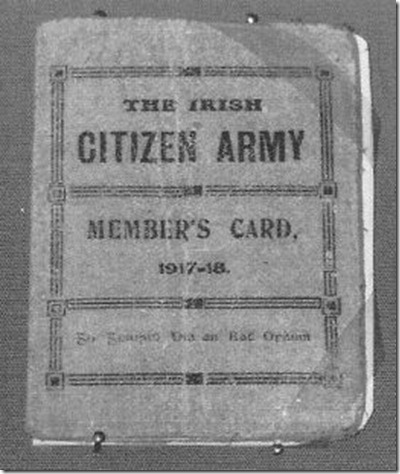

In 1916 Willie Halpin and his family were living at number 6 Valentine Terrace , now incorporated into West Road. Willie ( aged 29) worked as a plater in the Dublin Dockyard, was a trade union activist and a member of the Irish Citizen Army. His wife Tilly (nee Matilda Henry) was also politically active, and was a member of Cumann na mBan .

Hawthorne Tce and Ravensdale Road

The Halpin family had their roots in Wicklow, and the genealogical research undertaken by others contains many fascinating stories and connections , including involvement with the 1798 uprising and even an attempt to rescue Robert Emmet from the executioner! William’s parents were Edwin and Marianne Halpin ( from Wicklow and Wexford respectively). They had married in 1883 and had lived in East Wall for many years. Edwin was a telegraphist and for some time worked at sea. Edwin and Marianne had four children who died, and four who survived. William, the eldest, had been born in Wexford, his sister and two brothers in Dublin. The family originally lived in 26 Hawthorne Terrace, where they were direct neighbours to Sean O’Casey and his family. Edwin is described as being socialist in his outlook, and a Gaelic Revival enthusiast. He encouraged his children – William, James, Cecil and Bridget – to speak both the English and Gaelic languages. It has been claimed that Edwin was an influence on O’Casey – apparently Edwin and Marianne “conducted little theatricals in their home, which were attended by everyone on the street. O’Casey attended and sometimes took part and after the shows were over, stayed behind with others to listen to Edwin talk radical politics”.

Stories mentioned of the family’s earlier years in East Wall recall Edwin receiving a gallantry award, while working as a Marine Fireman, along with 10 shillings and a vellum testimonial from the City of Dublin Steampacket Company for saving Margaret Winter, an elderly female passenger from drowning in the Liffey at Sir John Rogersons’ Quay on the 17th December 1905. His gallantry was later recognized by the Royal Humane Society in February 1906. However, tradition also records “Bailiffs bursting into Hawthorne Terrace and cleaning the house of all its contents”. This may explain the family’s move to 22 Ravensdale Road by 1909. By 1912, Willie, now several years out of his apprenticeship, had moved to 20 Killarney Street and then, remarkably for a single man, acquired 6 Valentines Terrace on West Road in 1913. The following year he married Matilda “Tilly” Henry on the 3rd May at St. Laurence O’Toole’s Roman Catholic Church on Seville Place.

Trade Union Involvement

When John Smellie arrived in Dublin to open the Dublin Dockyard in 1901 almost all the skilled workforce had to be brought over from Glasgow. One of the legacies of this were the houses Smellie built for them on Fairfield Road, East Wall. However, from the very beginnings of the company Smellie had shown a commitment to employing local labour and despite lacking any family background in steelwork, Halpin, like many other local men, received the opportunity of training at the skilled and well-paying profession of Plater under the capable direction of William McMillan, the Dockyard’s Chief Plater and known as “the man who built the Helga.” Having served his time at the Dublin Dockyard Willie was admitted to the Amalgamated Society of Boilermakers and Shipbuilders on the 22nd November 1911.

The Amalgamated Societies were British Unions and popular among Irish workers as their cards allowed employment in Britain, America, Canada, and Australia. Given the ups and downs of employment in engineering industries in Ireland this was an important consideration for workers, as for many, emigration, whether temporary or permanent, was a fact of life. Halpin’s relationship with the Union was volatile, particularly once he became Foreman at the yard. He was expelled on 1st November 1922, readmitted in October 1924, suspended again in May 1927 and readmitted on 2nd December 1930. He would remain a member until his death in 1951.

The road to the Lockout

In 1909, a revolution in trade unionism was to begin, when Jim Larkin left the National Union of Dock Labour (NUDL) and founded the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. The ITGWU, “Larkin’s Union“, represented a new form of organisation amongst the workers of Dublin. Its approach of “One Big Union” and it’s motto of “An injury to One is a concern of All” broke with the tradition of sectional “craft” unions and brought un-skilled and casual workers into the fold. Its tactic of the sympathetic strike found great resonance amongst dock labourers, carters etc Willie Halpin like many locals would have been drawn to its ideals although a member of a different Trade Union. (Over 35% of the Irish Citizen Army were members of Craft Unions rather than the ITGWU , while female members tended to be from the Irish Women’s Workers Union).The militancy of the union, significant victories against the shipping companies, and its growing popularity was not welcomed by all, of course. The Employers’ Federation, led by William Martin Murphy, decided to wipe out the ITGWU. In August 1913, the great Lockout began, an all out class war which pitched the workers against the bosses, with the Dublin Docks being a key battle ground.

“Labour clenches its fist” -The Irish Citizen Army

William Halpin would have witnessed much hardship during this time – the existing hunger and poverty were all made worse by the Lockout. He would have seen the behaviour of the local employers – evicting families from company owned houses at the height of winter, importing scab labour from Liverpool and Manchester and permitting these to carry revolvers, and the use of police and military to act against the striking workers. At the end of August two workers, James Nolan and James Byrne, died after being battoned on the Quays. Hundreds were injured by the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) and Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) on O’Connell Street. They also rampaged through working class districts, smashing up houses and assaulting tenants. While Willie’s Union was not directly affected or involved in these events, it is like that like Fianna member Gary Holohan, a member of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers employed at the Dublin Port Power Station on Alexandra Road, he became involved in the dispute outside of working hours. Many of his neighbours working at the Dockyard were political and would join either the Volunteers or ICA. There was also a volatile group of apprentices such as Frank Robbins (North Strand), Mattie, Eddie, and George Connolly (Lower Gloucester Street, brothers of Sean Connolly), John Nolan (North Wall), Michael Kelly, and Peter Carpenter (East Wall), all of whom were active in the Transport Union and were involved in actions relating to the 1913 strike.

It was against this background that the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) was founded. Jim Larkin announced from Liberty Hall that a disciplined force to defend the workers was needed, and they would “create from among the members of the Labour Unions a great Citizen Army.”

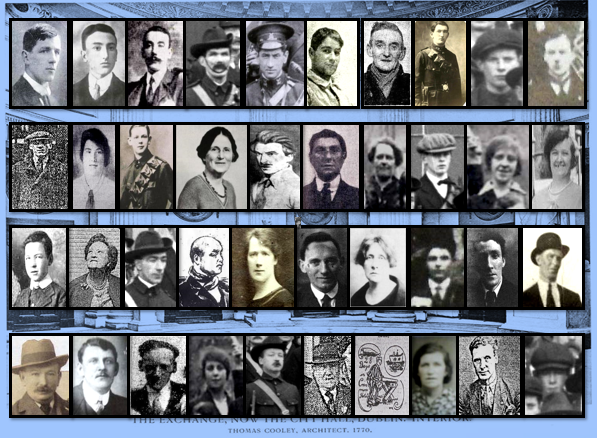

William Halpin was amongst a number of East Wall locals who joined the ICA in 1913. He was later to take up the position of Treasurer on the Army’s Executive on the 14th November 1914. Led initially by Jim Larkin and later by James Connolly, amongst the many prominent names associated with the Citizen Army were Rosie Hackett, Kathleen Lynn, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, Captain Jack White and Countess Markievicz. Sean ‘O Casey was its first secretary. O’Casey was eventually to leave following disagreements with Countess Markievicz, primarily over her connections with the Irish Volunteers.

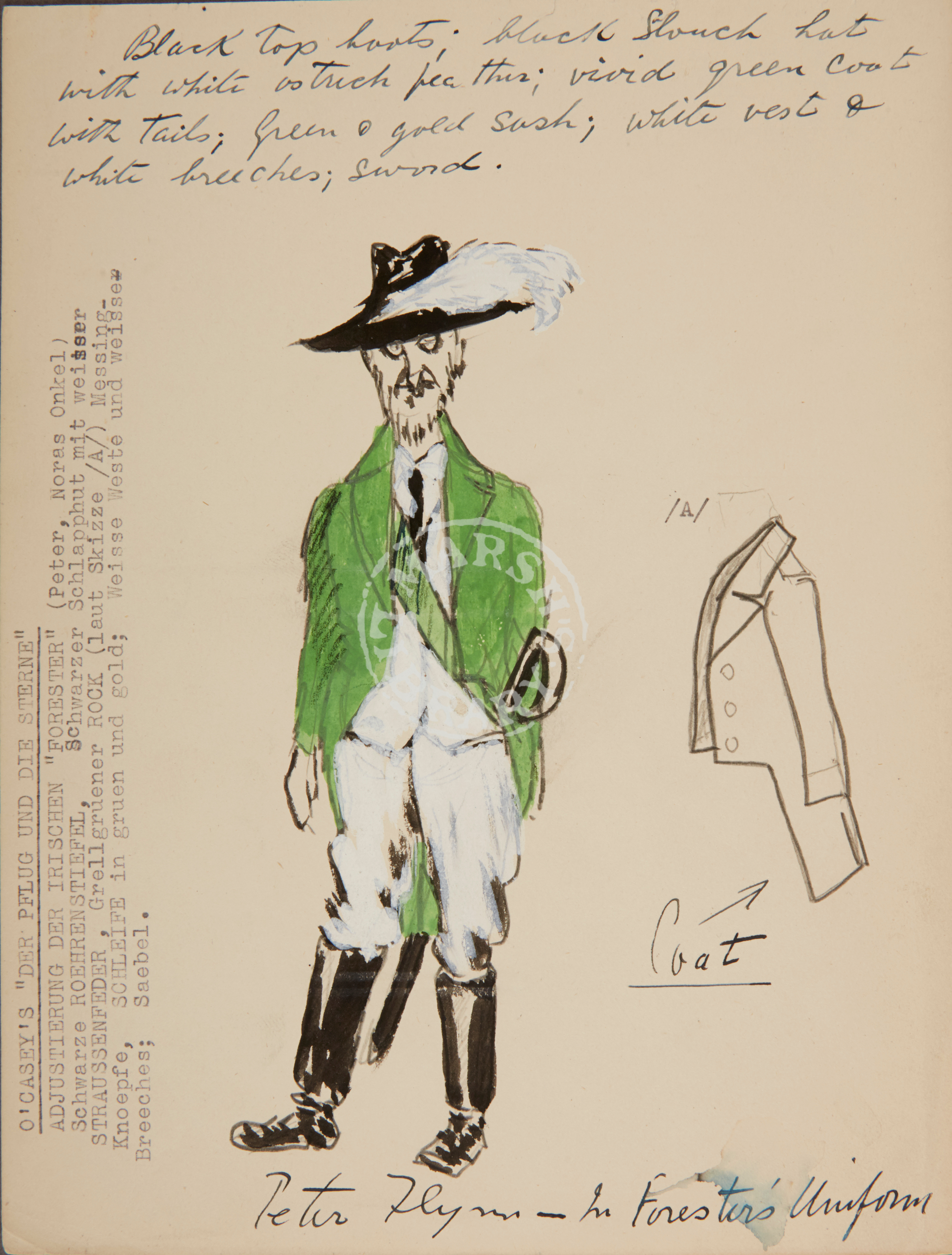

While the role of the ICA during the Lockout was hugely significant, it is its role in the 1916 Rising that it is most commemorated for. However, there was some distance to travel between these two historical events, and it was not always smooth travelling. Jim Larkin left Dublin for America in 1915, and would not return until the 1920′s. According to his own account written in 1919 Sean O’Casey stepped down and was “replaced as Secretary by J. Connolly, and afterwards Sean Shelly, Michael Mallon, W Halpin, and M. Nolan were included on the Executive.” (O’Casey remained very bitter about this period and it is certain that the character of Peter Flynn in his play ‘The Plough and the Stars’ was a satire of Willy Halpin).

The Irish Citizen Army was a workers’ militia – Citizen Army volunteers had to be members of a trade union (“if eligible”) and its goals were unashamedly socialist in nature. Later in 1913 the Irish Volunteers were formed and were led by Eoin Mac Néill. Their goals were nationalist in nature, their support more cross- class than the Citizen Army, including some who would have been indifferent and even hostile to working class and Labour movement ambitions.

The important role played by James Connolly in uniting the two strands was described by Citizen Army member Helena Molony: “The 1913 Strike was a complete rout. Ninety per cent of the workers of Dublin were swamped in debt, and many had not a bed to lie on. The only thing left that was not smashed beyond repair was the workers’ spirit, and lucky they were to have a man of Connolly’s stature to lead them. The ideal of National as well as Social freedom, which he held up to them, gave them a spiritual uplift from the material disaster and defeat they had just suffered.”

At the start of his working life Halpin had joined the Round Tower Branch of the Irish National Foresters Benefit Society. Founded in 1877 to bring Irishmen of all classes and creeds together to aid those who were ill, out of work, or in need of financial assistance for funerals, the organization grew rapidly to encompass 250,000 members worldwide by 1914. While its main purpose was to provide benefit for ill or out of work members it had a strong political agenda and its constitution aspired to “a government for Ireland by the Irish people in accordance with Irish ideals and Irish aspirations”. They also wore colourful gold-braided militaristic uniforms at their parades and meetings which would appear to have had an important influence on the young William Robert Halpin. (The discovery of a number of Foresters uniforms after the Easter Rising , including two in the Docklands area,lead to searches by the British military who mistakenly belived they belonged to rebel ‘generals’ who had escaped. It is likely that Halpin was wearing such a uniform at City Hall and provided inspiration for the Sean O’Casey characterisation of Peter Flynn).

In 1909 Fianna Eireann was founded to counteract the British influence of Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout movement placing an emphasis on recruits learning Irish history and culture. Halpin joined the Robert Emmet Sluagh based at 10 Beresford Place, then the HQ of the embryonic Irish Transport and General Workers Union. Nearby neighbours included the Seery family three of whom fought in the 1916 Rising. Many of those in the early version of the Robert Emmet Sluagh would go on to form the Citizen Army Boys Scouts and later join the ICA itself. Gary Holohan, who joined the Robert Emmet Sluagh in 1910 recalled it had about 20 members at that time. His first encounter with the Tri-colour was at No.10 and it was Willie Halpin who introduced him to it and explained its origin and meaning. Halpin remained with the Fianna until the formation of the ICA in 1913.

The Great War- “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity”

In 1914 the “Great War” broke out in Europe, and the British Empire went to war against Germany. The War was seen as an opportunity to advance the cause of Irish Nationalism, but how to do this divided the volunteer movement. Leaders such as John Redmond actively encouraged recruitment into the British Army, in the belief that by doing so Britain would grant Home Rule after the war ended. Others, such as Pádraig Pearse , believed that an armed rebellion was necessary. The Citizen Army, under James Connolly, was opposed to the imperialist war and famously hung a banner across Liberty Hall proclaiming: “We serve neither King nor Kaiser, but Ireland”. They prepared for military action against British Rule. While they were prepared to fight alongside the Volunteers to achieve this, they were conscious of what they saw as the limits of Nationalist ambitions, and Connolly famously stated shortly before the Rising: “The odds are a thousand to one against us, but in the event of victory, hold onto your rifles, as those with whom we are fighting may stop before our goal is reached. We are out for economic as well as political liberty. Hold on to your rifles”. Citizen Army men like Halpin would have been very aware that within the broad nationalist movement there were those who had not only failed to support, but had actively opposed the workers in 1913.

The Great War – A house divided

The difference of attitude not only divided the Volunteer movement, but often divided families too. There were a multitude of reasons why Irishmen joined the British Army – because they believed Ireland would be rewarded with Home Rule, some did feel allegiance to the Crown, and some for purely economic reasons. The pressures of “economic conscription” were felt greatly in Dublin. In contrast to grinding poverty, unemployment and casual labour – the British Army paid well, soldiers wives received a separation allowance and it also offered an opportunity to develop marketable skills and crafts.

William’s two brothers both signed up to the British Army. They were aged only 15 and 16 at the time and lied to recruiters. William travelled to their barracks in Ulster to have them released from service. This failed, and he had to raise the money to buy them out. The pair were ‘bounced and battered’ all the way home. This obviously wasn’t enough to convince them, and both would later re-enlist.

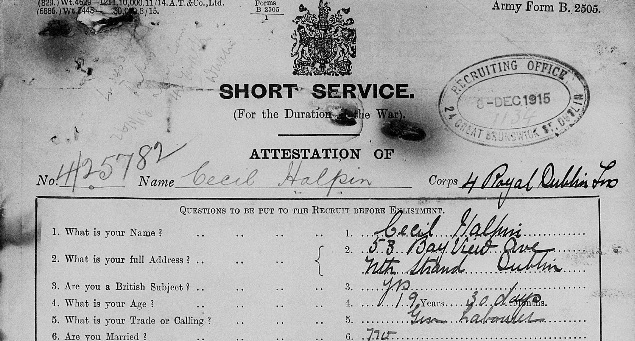

While little information on James army service survives there is an extensive collection of papers relating to Cecil. At his second attempt Cecil joined the 4th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers on 8th December 1915 giving his age as 19 years and 30 days. Cecil had been working as a Blacksmith’s Striker in the Docks and must have known many of his older brother’s friends and associates. At the time he gave his father’s address as 53 Bayview Avenue, but given that Edwin and the rest of the family were still living at Ravensdale Road in 1918 it may have been a false address. He seems to have had a falling out with his father as he would advise the War Office to send all correspondence relating to himself to his married sister living at Stella Gardens in Inchicore.

The 4th RDF were a service Battalion training recruits to be sent up the line to replenish the losses of regiments then fighting in France. Cecil wasn’t sent to France until 18th July 1916 and given his regular outbreaks of psoriasis which required medical treatment it is almost certain that he was in Ireland for the outbreak of the Rising in April that year. The 4th RDF arrived in Dublin on Easter Tuesday and largely served in the North Inner City between Broadstone and Amiens Street. However, units of the 4th were present during the bombing of Liberty Hall and it seems at the attack on the then empty Daily Mail Offices on Parliament Street as the fighting at City Hall was being brought to a conclusion. This may well explain animosity which is believed to exist between Willie and his younger brothers . On the 25th June 1916 Cecil was noted as absent from his regiment which may have been an attempt to contact his brother who was hospitalised in the Dublin Castle Hospital for a number of weeks and subsequently at Richmond Barracks after the Rising. It cost him three days detention in the guardhouse. He made another attempt three weeks later with similar consequences. If Cecil was attempting to make contact with Willie to explain his position in relation to the Rising that conversation never took place and the gap of several years before they would see each other again would have allowed hostilities to fester.

Cecil injured his leg while in Ireland which would eventually see him honourable discharged from the British Army on the 13th February 1918 with a pension of 2/6 per week. It would be ironic if the injury had been picked up during the Rising as Willie would complain of a similar injury sustained at City Hall where he was struck by the butt of a rifle during the fighting.

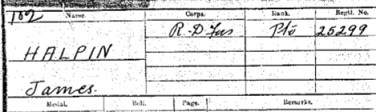

There are few records surviving for James, other than that he served as a Private in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and received the Allied Victory Medal and British War Medal at the end of his service. However, if he had joined the 4th RDF at the same time as Cecil, and potentially found himself on active service in Dublin in 1916, it would explain much of the subsequent difficulty between the three brothers. At some stage James was shell-shocked, suffering from the effects of poison gas and left unable to speak. He spent a considerable period in Leopardstown Hospital in Foxrock before recovering. (James was considered a very proficient marksman, as too was William).

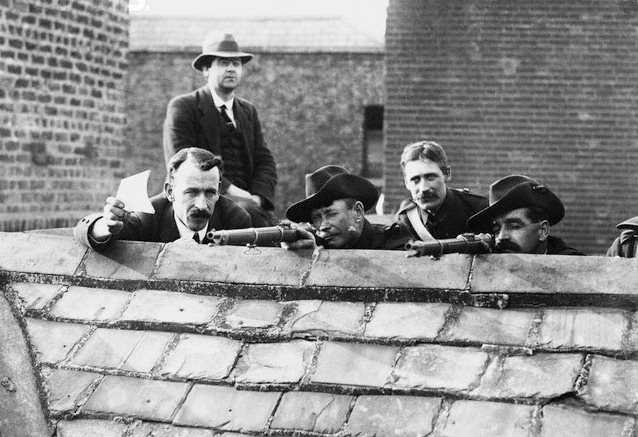

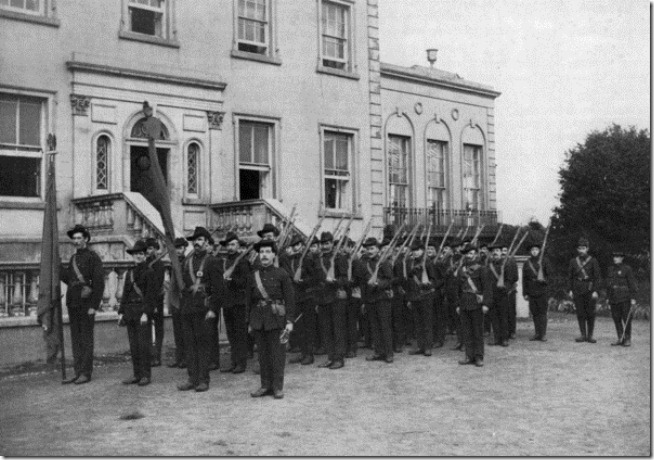

Citizen Army in Croydon Park , William Halpin on right (with sword!)

“Napoleon” or “Robert Emmet” – personal recollections of Willy Halpin

Frank Robbins from North William Street was a trade unionist and Citizen Army member who worked for a time with Halpin in the Dublin Dockyard. His statement to the Bureau of Military History is the most extensive first-hand account of the ICA available, and formed the basis of his memoir “Under the Starry Plough”, published in 1977. However, Robbins was little more than a youth at the time of the Rising and while he knew Halpin’s somewhat older circle of Ellet Elmes, Tom Leahy, and Alfred George Norgrove he was on the periphery of much of their activities . Following the 1924 split in the Transport Union he was ostracised by many ICA veterans who had supported Larkin and went with the newly formed Workers Union of Ireland. However, he does give some details of Halpin’s early role, describes his small stature, and recounts a number of amusing anecdotes:

“The supply of arms was very poor. This was, to a very limited degree, countered by some of us who were very eager, and who could afford to see in our hands more up to date weapons than the Howth rifle. (The German Mauser of 1871 was used in the Franco-Prussian War and was named the Howth rifle as a result of the gun-running). We set about organising rifle and revolver clubs; as well as uniform clubs. This was accomplished by paying a subscription of one shilling per week to the rifle club and sixpence per week to the revolver club. By this means a number of us became the proud owners of what was known as the Boer Mauser, which had a magazine of five bullets and one in the breech. We were the envy of our less fortunate comrades whose lack of means prevented them from doing as we had done. The secretary of the club was William Robert Halpin. He was then, like myself, employed in a Dublin Shipyard.”

“On occasions ripples appeared on the water, indicating some little personal grievance amongst members towards each other. I have already mentioned William Halpin. He was small in stature, formerly an active member of the Irish National Foresters. He took it on himself to appear not exactly in the dress of an officer but in something very similar. His uniform evenincluded a sword! … After one of our many parades Connolly asked the usual question “Has anyone anything to say?”Lieutenant John O’Reilly stepped forward to ask Connolly if Halpin was an officer of the Army, and if not why he did not march in the ranks the same as the other men. O’Reilly insisted that this must not be tolerated any longer. Connolly, his eyes twinkling with merriment jokingly replied, “Every regiment is entitled to its mascot”, and so ended the frontal attack on Halpin. Connolly was not the only one who had a sense of humour for such occasions”

“Halpin always endeavoured to impress upon his listeners, off parade as well as on parade, his higher knowledge of things which were happening or supposed to be happening… on various occasions on our way home at night a centre of call was Holohan’s shop in Amiens Street near the Five Lamps, where cigarettes and othernecessities of that kind could be had. George Norgrove and Elliott Elmes prepared many a story for Halpin’s benefit, the rest of our party always ensuring that Halpin was delayed somewhat so that the story concocted for his benefit would be given to either of the brothers Holohan for relay.We would eventually gather together again at the corner of Seville Place to hear our story relayed back to us by Halpin. Elmes was a droll character, small like Halpin, but of better build. He knew Halpin very well and alwaysreferred to him as “Robert Emmett” or”Napoleon”. Many tears of laughter were shed by our little group because of the funny stories told by Elmes, and the way they were told was a treat. All this was fun which Halpin took in good spirit on the occasions when he knew the joke was on him.”

In old Dockland parlance there is a saying that someone is “a bit of a consequence.” The reference is to someone slightly better educated and well-read who not only understood “big words” but used them in their everyday conversation. Sean O’Casey would have been a prime example but so was Willie Halpin. People tended to make fun of them behind their backs but when an official letter arrived in the door or they needed to make an application for something, “the Consequence” would be their first port of call for assistance if their parish priest was unavailable. ICA members might joke about Halpin and lay “traps” to have a laugh at his expense, but they also voted him in as Treasurer in 1914 and onto the Army Council the following year. Unlike the Irish Volunteers the ICA was a democracy and all appointments to the executive were by popular vote of the membership.

As Treasurer of the ICA Willie Halpin not only chased up members for their dues and contributions towards their uniforms and other equipment but he was also involved in financing the buying of rifles from soldiers and sailors quite often from ships in for repairs at the Dockyard. The Dockyard had acquired a repairs contract with the Royal Navy in 1914 and according to Halpin his job as foreman of the platers “gave him easy access to some of His Majesties Boats” and this made it possible to “bring off certain coups.” Joe Good, who met Willie after his capture described him as, “utterly honest” and carried the ICA “war purse” in the run up to the Rising which ran to thousands of pounds for the purchase of requisitions and arms. Good was amazed that he had kept “this large sum in his humble home” as he didn’t trust banks. James Connolly may have playfully described Willie’s eccentricities as being due to his being the ICA’s “mascot” but he trusted him implicitly with the organizations finances. When Halpin returned to the Dockyard after the Rebellion this experience would place him in a central role in implementing the ICA’s importation of arms from Glasgow through Dublin Port using mostly female couriers from 1917.

( William Halpin, Frank Robbins (39 North William Street), Elliott Elmes (32 Leinster Avenue) were all Citizen Army Men working in the Dublin Dockyard, joined later by Thomas Leahy (12 Sheriff St / 3 Abercorn Tce), who was in the Volunteers up to 1916 and afterwards transferred to the ICA).

From Workers’ defence to Insurrectionary force

The importance of Citizen Army men in the Port area has been highlighted in the past – as well as being valuable eyes and ears they also had access to transport and could assist in the movement of men and equipment. Those working in engineering had access to skills, equipment and materials useful to an army preparing for battle. Grenades and bombs were ‘home-made’ and there was even an ambitious attempt to manufacture their own rapid-fire machine gun based on a plan brought back from Mexico by John Hughes of St. Mary’s Road. Having discussed the realities of street fighting, the possibility of knocking through walls into adjoining premises was raised. According to Robbins they recognised

“…the necessity for instruments suitable and necessary to aid in this work. Sledge-hammers were regarded as one of the best instruments and members of the Citizen Army were asked to supply them, and to use their own ingenuity as to how this supply could be obtained. A number of members of the Citizen Army were working in the Dublin Dockyard and other kindred employments, and very often it was found that two or perhaps three Citizen Army men would have their eyes on the one sledge-hammer. I have to confess that I did, without the knowledge or the sanction of the Dublin Dockyard Company, relieve that Company of many of their 7-lbs. sledge-hammers, and for which I had the unwanted kind of prayers of many of my fellow-workers in the Dublin Dockyard who lost these valuable tools. Other articles among the many which the Dublin Dockyard Company lost from time to time were files, pieces of lathes, and borings, the latter being used in the preparation of home-made bombs.”

In fact, so many tools and pieces of equipment were pilfered from the Dockyard that the Foremen became vigilant and began to examine suspicious workers as they left the premises. In later years when equipment went missing the humorous explanation used to be “there must be another revolution coming soon.”

Drilling, marching, first aid and weapons training all became common place during these years. Firing ranges were set up by the ITGWU at Croydon Park and in their premises in the basement of Liberty Hall, at Cornmarket, and in their branch offices at James Street. The Citizen Army men took part in a number of competitions with members of the volunteers and gained a reputation for their superior skills. Route marches took place regularly in the City, and under the ever-watchful eye of the police mock attacks on key targets took place. As well as being useful for training purposes, these marches were also designed to fool the authorities, in the hope that when a real attack was planned they would mistake this for a drill. One regular target for these ‘mock attacks’ was Dublin Castle, the centre of British Rule in Ireland. According to one eye-witness account of the Rising this approach had some success in blind siding the authorities, but also led to some confusion amongst rebels who were unsure if this was the real thing and hesitated in their attack.

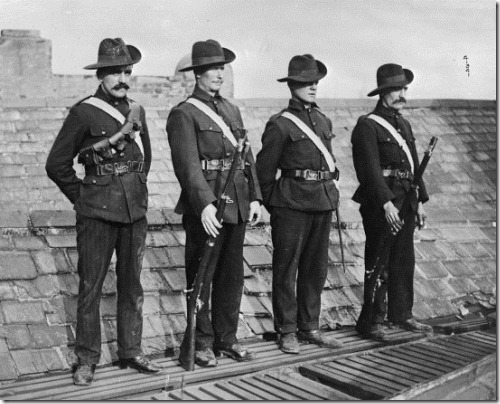

Guarding Liberty Hall

As the date for the rebellion approached Liberty Hall became a centre for preparations and propaganda, with a weekly paper The Workers Republic printed here. At one stage an attempt to seize papers was prevented by James Connolly and Helena Molony who turned away the police at gun point. This led to an urgent mobilisation of the Citizen Army, and the sight of men rushing off the job and heading from the Docks to Liberty Hall has been vividly described:

“Men left their employment under the strangest conditions on that day. Some who were carters and had horses to look after turned them into the stables; others brought them to Liberty Hall. Many black-faced men cut a peculiar figure rushing through the streets of Dublin on bicycles or on foot with full equipment rifle or shotgun, bandolier and haversack etc.”

Citizen Army men in the Dublin Dockyard, including William Halpin, Robbins and Elmes were amongst those who left their workplaces to protect Liberty Hall, and some were afterwards brought before the foreman for their actions. Liberty Hall remained under constant guard from this time, including the days immediately prior to Easter 1916 when thousands of copies of the proclamation were produced on the printing press here.

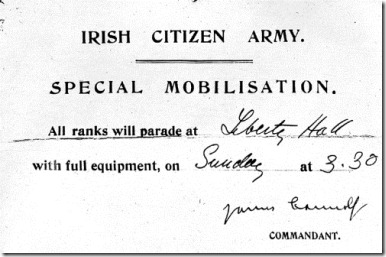

“Are you prepared to fight…?”

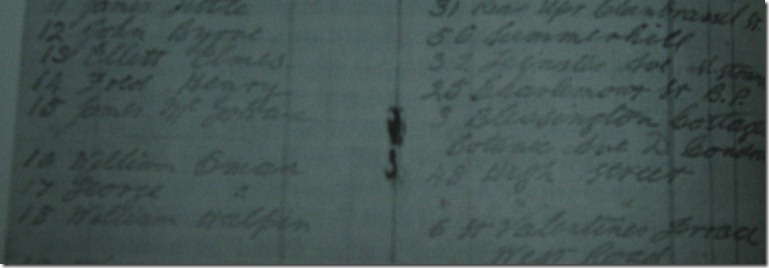

Before the final planning stages of the Rising were entered, James Connolly had been fearful that the Irish Volunteers would not carry through with launching an attack on the British administration. A special meeting of the Citizen Army was held in Liberty Hall. Afterwards, members were taken individually into a room with James Connolly, Michael Mallin and Thomas Kain (mobilising officer). They were each asked three questions: Were they prepared to take part in the fight for Ireland’s freedom, were they prepared to fight alongside the Irish Volunteers, and were they prepared to fight without the aid of the Irish Volunteers or any other military force? If they were agreeable to all three questions, they were given a secret mobilisation number. William Halpin’s was number 18. He had virtually given up home life for several months returning daily to Liberty Hall from work at the Dockyard to prepare for the upcoming conflict.

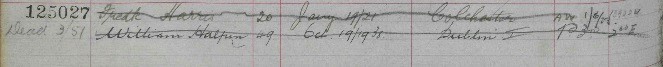

Citizen Army membership list 1916

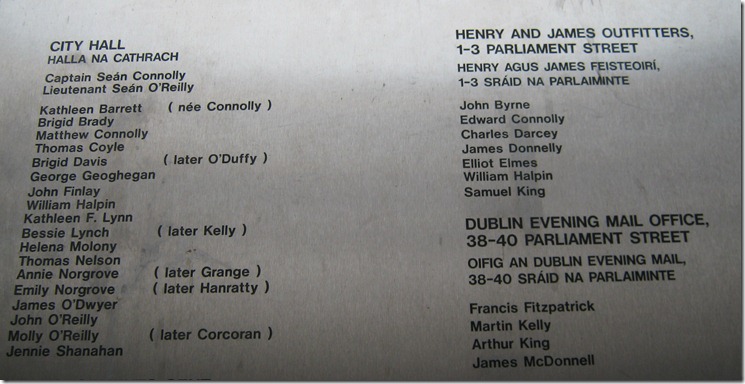

Easter Rising – City Hall

What is now known as The City Hall Garrison was in fact a simple but potentially effective plan of surrounding Dublin Castle with 10 outposts – later reduced to 8, due to a shortage of man-power. (The two locations dropped were to cover the Lower Castle Yard). This would make it impossible for the British Authorities to use the Castle as a point for counteracting the Rebellion and provide a hugely symbolic blow to British Rule in Ireland. It demanded precise timing, something ICA Commandant Michael Mallin suggested the Citizen Army would struggle with, and the main flaw with the plan was the reliance on men from the 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade Irish Volunteers, then at Jacobs Biscuit Factory, to man a strategic number of tenements on Upper Stephens Street which covered Ship Street Barracks at the rear of the Castle, with very little advance notice. The failure of the Volunteers to try and occupy these before 9.00pm that evening was almost certainly one of the main factors in the failure of the plan.

The force consisted of 32 men and 10 women later augmented by two stray members of the Irish Volunteers who had lost their companies. Much is made of the military experience of ICA members, however the full complement of veterans in this group was two, George Geoghegan, a one-time member the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, and Tom Daly, formerly of the Royal Artillery. Geoghegan would be killed during the fighting. Crucially this was the only ICA Garrison whose Commander had never fired a shot in anger.

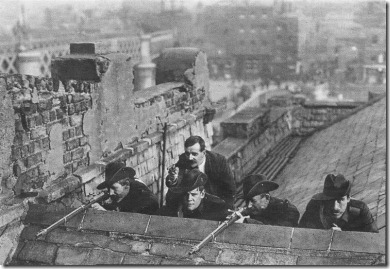

Sean Connolly, Commander of the City Hall Garrison, had cut his thumb badly the night before and worried whether he would still be able to fire a rifle. His force was to be in place by 12.00pm however they only left Liberty Hall at that time and although they were running late the ICA chose to pick a fight with some locals on Dame Street which would see Connolly badly cut in the hand before he could extricate them. Now severely late the precision of the plan was quickly coming undone and may explain why Connolly, under extreme pressure, shot Constable James O’Brian at the Castle Gates. Ironically, Willie Halpin, the first man into the City Hall having broken through the basement entrance on Exchange Court (now the entrance to the interpretive centre), was coming around behind O’Brien from inside the Castle so he could have been easily overwhelmed and captured. The shooting of O’Brien seemed to panic the contingent and some began to open fire at nothing in particular.

The main fighting force should have occupied the Rates Office, the roof of which is a natural fortress, but as one soldier’s rifle jammed he ran back to the City Hall for cover and others seem to have followed him leaving Jack O’Reilly and John O’Reilly (no relation) as the sole occupants. Several went walkabout in the Upper Castle Yard astonished that they were standing there under arms.

Roof of Rates Office. A natural fortress and the only roof to overlook the Bedford Tower. (Photo: Hugo McGuinness)

Poor intelligence would see Thomas Kain’s group unable to penetrate from the Main Guard to the Bedford Tower and they inadvertently barricaded themselves out of the fighting. The failure to occupy the Bedford Tower would be crucial and contribute to the high casualty rate sustained by the ICA during the fighting.

The Synod House group at Christ Church Place had been told that British troops would stop and take cover once they opened fire on them. They didn’t, and the three men in occupation, Tom Healy, John O’Keeffe, and Pat Byrne, were all wounded as Grant simply urged his men past them.

Running late, Bill Oman’s small group of three was quickly reduced as one of them fell and injured his back climbing the wall of St Werburg’s Graveyard to access the rear gate viaduct of the Castle at Ship Street. It soon became apparent to Oman that his other companion, Pat Williams, was shell shocked from the encounter with O’Brien. Left with home-made bombs which failed to explode, all he could do was abandon the post as the 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers under Lieutenant Charles Grant walked into Ship Street Barracks. Meanwhile another company of Royal Irish Fusiliers under a Colonel Tighe, having come under fire in Castle Street, simply walked down the Castle Steps and around the corner through the Ship Street Gates.

The British entered the Castle taking possession of Ship Street Barracks and then the Bedford Tower shortly before 2.00pm. Snipers were spread around the Castle complex and shortly afterwards Sean Connolly was killed, according to Bridget Brady, by a sniper at a window in the Castle Hospital. Jack and John O’Reilly then left the Rates Office to cross to the City Hall and both were shot in Exchange Court, Jack O’Reilly, 2nd in Command of the Garrison, being killed outright. In quick succession several of the attackers on the roof of the City Hall, John Finlay, Tommy Coyle, and Thomas Nelson, were picked off and Mattie Connolly, having witnessed his brother’s death was in shock.

The British snipers now targeted the women still on the rooftop. Seeing Helena Molony dressed in what appeared to be a green military uniform Lieutenant Grant opened fire on her leading to the evacuation of the women to the lower levels of the building. The remaining defenders must have quickly realised that they were on a roof that was indefensible.

Nearby, Charles Darcy, on the roof of Henry and James on Parliament Street exposed himself to British fire and was also killed. William Thomas Halpin, a butcher from Dominick Street, was Shell Shocked early in the fighting at Henry and James and went to the G.P.O, and over at the Mail Office Frank Fitzpatrick fell from the roof and had to retire for treatment. By 4.00pm only 3 outposts were left operational and for those on top of City Hall it must have dawned on them that this building, with its mass of roofs and lack of defensible positions, all overlooked by the Bedford Tower, was now a killing field with its defenders waiting to be picked of.

On City Hall – series of roofs (overlooked by Bedford Tower) with few defensive points and impossible to defend. (Photo Hugo McGuinness)

Lilly Stokes, a VAD Nurse in the Castle Hospital heard a commotion in the hallway and on investigating was told by the snipers operating there that they had killed the first Rebel Commander (Sean Connolly), then killed his replacement (Jack O’Reilly), and they had now identified the new commander of the rooftop fighters and were going to kill him. Stokes was shocked, but the celebrations continued and for the next 24 hours the “new man” would be the main target of the British as they retook control of Dublin Castle.

The new “man in charge” according to John Nolan and Molly O’Reilly was Willie Halpin, who organized getting the remaining women off the roof, set up some type of defence to counteract the snipers in the Bedford Tower, and generally brought some sense of organization to the chaos which was ensuing until a small group of reinforcements under Alfred George Norgrove arrived. Effectively this made Halpin the closest thing to the last Commandant of the ICA at City Hall. Unfortunately, Halpin’s eccentricity and fondness for ostentation on his uniform, had seen him adorn it with gold braid and as usual he was “accoutred with a fine sword.” According to Joe Good he was “the picture of a very little chocolate soldier.” From the British point of view, he was easily identifiable and as the Garrison struggled to defend itself, Halpin became the attacker’s number one target.

The rear of City Hall where the British blew a section of wall out to attack the building. The damage is still visible. (Photo: Hugo McGuinness)

By 9.00pm the British, backed up by machines guns, were ready for their final assault and blowing a hole through the rear wall, they flooded the ground-floor Rotunda with machine gun fire killing Louis Byrne instantly. Shortly after this the Garrison in the lower part of the City Hall fell. Given a signal from Alfred George Norgrove, Dr. Kathleen Lynn, the ICA’s Chief Medical Officer, stepped out from the darkness as British soldiers poured into the building and surrendered the Garrison. Being a woman, this caused confusion among the officer in change and almost certainly saved the lives of many of the occupants as the British paused to figure out what to do. Some quick thinking by Jinny Shanahan convinced them that it was too dangerous to go up onto the roof and this greatly slowed down their advance. Halpin and his small remaining band of defenders had a sleepless night on the rooftop before being overwhelmed the following day suffering from exhaustion and incapable of offering resistance.

According to family tradition Halpin had paid £5 for his rifle and was reluctant to just hand it over so easily. Before the rooftop was overwhelmed, Halpin decided to hide it and hopefully retrieve it later.At the far, left hand corner of the building, you can reach out and touch Dublin Castle, there being just a small gap between the two buildings. Mattie Connolly, having gone into shock at the death of his brother Sean, had been brought down from the roof and sedated and placed in an office giving access to the City Hall’s Roof. On realizing the British were invading the building he grabbed his equipment and returned to the rooftop. He described hearing shots in the distance but on the rooftop there was “an eerie silence in the vicinity” the only light being “a strange surreal blueish light” from the arc lamp at the Daily Main Office across the road. He was unable to see any of the remaining fighters on the roof and it is likely that at this stage Willie Halpin may have chose to dispose of his rifle as the British were otherwise distracted. Remarkably the section at which the rifle is said to be have dropped, while not visible from the Bedford Tower is overlooked by the Birmingham or Record Tower accessed from the Lower Castle Yard. However, there is no evidence of the British using positions in the Lower Castle Yard to engage the City Hall Rooftop.

Section at rear of City Hall Roof where Halpin is said to have dropped his rifle over. (Photo: Hugo McGuinness)

.

At this point the though must have struck Willie that given the nature of his uniform and the fact that he had been targeted for the previous 24 hours by British snipers, that if he were captured he may well have faced a Courts Martial and the potential aftermath of an execution by firing squad. Being slightly built he managed to crawl into a chimney in the building and would remain there until Thursday.

From his hiding place Willie could hear British soldiers “lamenting the men they had lost in battle” so he was reluctant to come out. Exhausted and dehydrated through lack of water he was finally forced to surrender himself and was taken from the chimney with his sword scabbard dangling behind him. Nearly unconscious, a kindly soldier took a flask from his pocket and put it to Willie’s lips. The flask contained whisky, and Willie, a teetotaller, tasted the spirit for the first time in his life. He immediately went into shock and the Soldiers panicked. Gathering him up they took him to a room where a number of the Rebellion’s leaders were being held. Throwing him on the floor they shouted “here’s your Brigadier General!”

Helena Molony was later to comment: “Halpin was as brave as a lion. He did not surrender.”

“He had a very hard time up the chimney …”

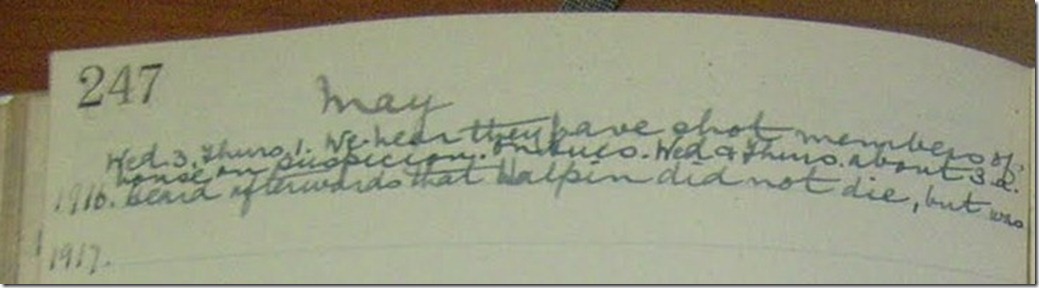

For a number of days Halpin’s comrades had feared him dead. A record of these concerns can be found in the diary of Kathleen Lynn, (doctor, ICA member and founder of St Ultan’s Children’s Hospital), which was written during the Rising. She originally noted his “death”, but on the 3rd of May she wrote “Heard afterwards that Halpin was alive and recovering slowly in Hospital”.

In her account of the Rising written years later she recalled: ” He was so small that he had tried to escape by hiding up a chimney in the City Hall; and down he came and was found afterwards. He certainly was black with Soot. He had a very hard time up the chimney, but he got alright afterwards.”

Following his near escape, eventual capture, and during his recovery period Halpin continued to worry about Tilly’s well-being. Father Aloysius, who administered to the rebellions leaders before their executions referred to Halpin in notes he took at the time:

“Again it is a pleasure to acknowledge goodness whenever and wherever it is met, and I must here record another act of humanity and kind-heartedness on the part of Lord Powerscourt. Meeting me at the Castle on the occasion of one of my visits to James Connolly he asked me if I could visit or get one of the Fathers to visit the wife of one of the prisoners – Wm. Halpin of the Citizen army. The poor fellow, he said, was anxious about the wife as she was in a delicate state of health when he was leaving home. Halpin, he told me, had been taken in an exhausted condition from a chimney and it would be a help and comfort to him if we could reassure him about his wife’s health, I undertook to visit Mrs. Halpin and Powerscourt said I could see the prisoner afterwards and at any time I wished.”

In good company

Following his recovery Halpin was transferred to England along with hundreds of other rebel prisoners. Documents from the time record that Halpin (listed as shipbuilder) was amongst a group of 25 prisoners “removed from Richmond Barracks on 15th June and lodged in Knutsford Detention Barracks”.

The paths of Citizen Army men from the Dublin Dockyards would cross briefly, before they all finally ended up together in Frongoch Internment camp in Wales.

Thomas Leahy,amongst the first prisoners sent to England, recalls these reunions of sorts:

“One morning, the last of the wounded prisoners arrived from Dublin Castle; this would be somewhere in the month of July, and I was very much surprised to find that two of them were very close pals and next-door neighbours. All three of us had started our apprenticeships in the same firm William Halpin ship plater; Elliott Ellems, driller. We did not get much time to make any arrangements for the future or enjoy our new-found company, due to the fact that I with others was ordered to pack up all our belongings and be prepared to be removed to an internment camp in North Wales, called Frongoch. We did not get the chance of saying goodbye, but we did meet again some weeks after at the camp.”

Amongst other prisoners Halpin spent his time with in Frongoch was Peter Carpenter whom he had known in East Wall and was also an ICA member. Peter had seen action alongside Thomas Leahy at Annesley Bridge and in the G.P.O before their capture. Peter’s brother , Walter was o/c of the Citizen Army Boys Corp, and had narrowly avoided capture himself at the G.P.O. (Their father was the Walter Carpenter of Caledon Rd , jailed in 1911 for insulting King George).

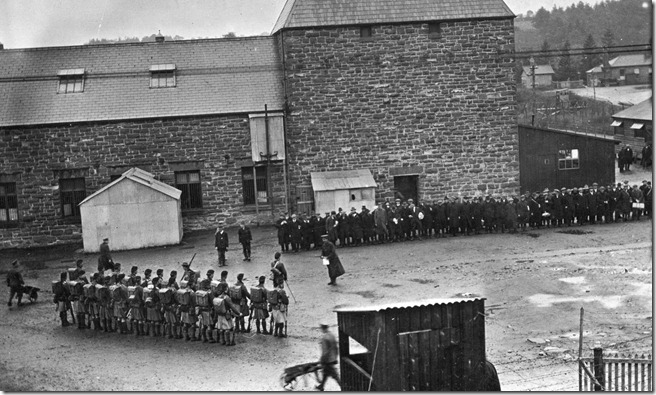

Frongoch later became known as the “University of Revolution“. Granted prisoner of war status, the men implemented their own command structure and used the opportunity of their incarceration to drill, train and engage in intense political education and debate. It was here that the organisation that was to prove so effective against the British Authorities between 1919 and 1921 took roo

Frongoch internment camp

“…towards the struggle to come“

William Halpin was freed as part of a widespread release of Republican prisoners. Back in East Wall by early 1917 he was to continue his activities as a trade unionist and also his involvement in military activity against the British administration.

These accounts by Thomas Leahy of his own his post Frongoch experiences can be reasonably assumed to be a similar story to Halpin’s and reflect a similar mind-set:

“After a week or so, I got employment in my old firm, The Dockyard Co… I was pleased to see the new spirit in the people. No time was lost in putting into practice the lectures, instructions and what had to be done, as laid down in the prison and camps. All of the year 1917 was taken up with reorganising, recruiting and taking part in all events towards the struggle to come… We also had to find work for our men. The young men had become more interested than formerly, and were joining the Volunteers and Citizen Army, which was a good sign. They never spared themselves or thought time too long when asked to work for any purpose connected with the fight for independence. Many hard nights were spent by them in the Dockyard and railway shops, together with drilling and learning the use of arms or raiding for them, the political side was still looked after by the leaders, and meetings, lectures and concerts were organised for funds and, in many,cases, broken up by the police. Arrests were quite frequent for the simplest act, or for helping in any way.”

“The work went on making train wrecking tools, hand bombs and everything that would be handy and useful when required. Several British naval vessels came to the Dockyard for repairs as the firm was on the Government list for such and several raids were made on these vessels for arms when most of the crew were ashore. Any other ships we thought had arms were searched also.”

“…a shower of sods ” on Church Road

During 1918 crucial elections took place, which saw Sinn Féin win a resounding victory across the country, seen as a legitimate mandate for Irish Independence. In the North Dock Ward the candidate was Phil Shanahan, who went up against Alfie Byrne (who had been a hate figure for Larkin and the ITGWU years earlier). During the election campaign street violence broke out in East Wall -

“During one of our meetings down the Church Road, or East Wall, we met with a very hostile crowd who were mostly all Scotch people working in the Dockyard, and the followers of Alfie were also strong there. When I rose to open the meeting and to introduce Sean T. O’Kelly and Jim Lawless, also Phil Shanahan, we were met with a shower of sods and Union Jack Flags waving all around us, but it did not last long, as the precaution was taken before hand for this, and acompany of 2nd Battalion Volunteers were near at hand and, with batons, cleared the place of the objectors in quick time. We were allowed to hold our meeting without interruption after that. After the election was over and results known there was great rejoicing in the North Wall camp and a great blow to Alfie Byrne and his followers.”

Jim Lawless was also a significant figure and the local support for the independence struggle is illustrated by the men literally putting their money where their mouth was:

“When the Dáil Loan was floated, I was instructed to collect for it in my firm and right well it was taken by the workmen, who bought shares from £1 to £10, paying up weekly. I handed over all monies every week to Jim Lawless, who was responsible to Mick Collins, Minister for Finance at that time.”

British troops at junction of O Connell St. and Abbey St. in 1920

War of Independence –

In purely military terms, the 1916 Rising was a failure. However, the rebellion and subsequent events created a dynamic which were to lead to were to lead to the War of Independence, the treaty of 1921 and the establishment of the Irish Free State.

Thomas Leahy commented following the establishment of the first Dáil in 1918: “Shortly after that event we of the Citizen Army kept in touch with the Volunteers and came to an understanding for co-operation in all orders that might be issued.” The Citizen Army maintained a separate identity to some degree, but the Irish Republican Army emerged as the military challengers to British Crown forces.

The years 1919 to 1921 saw Dublin City suffer greatly, with Guerrilla warfare fought out on its streets. Black and Tans and auxiliaries terrorised the population, ambushes and assassinations by Republican forces were common place and gun battles were regular and a source of great danger to civilians. The Dock area witnessed much of this, with the British military based at North Wall Quay and particularly infamous incidents such as the burning of the Custom House. Between February 1920 and July 1921 a strict curfew was imposed,the impact of which is described in Padraig Yeates A City in Turmoil:

“There were some unexpected complications arising from the enforcement of the curfew in Dublin Port. Thick fog hampered operations on the quays, although the Port and Docks Board had its own power supply for lighting. An even bigger problem was the refusal of dockers to work late if it meant they would be stranded in the port during the curfew. They absolutely refused to berth ships between midnight and 5 a.m., regardless of the tide. As a result the time for turning around a vessel frequently doubled. The average delay experienced by colliers rose from 12 hours to 26, exacerbating the coal shortage in the city. The movement of herds for export also required careful timing now that the cattle market could not open until 6a.m. and animals could not enter the city and be driven through the streets to the docks only when the curfew ended.”

**********************************************************************************************************************************

(This section is due to be extensively extended based on new research)

***********************************************************************************************************************************

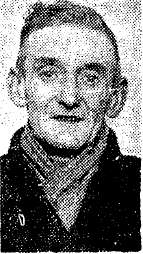

Treaty , Civil War and afterwards.

Halpin opposed the treaty of 1921, on both socialist as well as republican principles as did many in the Citizen Army. He fought on the Republican side during the Civil War and was injured by a Bomb during an attack in Bolton Street. After recuperating he went on the run and continued with the Anti-Treaty Forces up to the cessation of activities in 1923. In subsequent years, he had his own way of commemorating those he had fought alongside. It has been said that every Easter his family would gather around a flagpole in the front Garden and honour the fallen of 1916. One of his daughters was named Constance, after Countess Markievicz – Citizen Army officer and the first Minister for Labour (1919-22). He also served with the ARP (Aghaidh Aer-Ruthar or Air Raid Protection) Corps as a Warden during the Emergency 1939 –‘45. Given the events of the time it is possible he assisted in the rescue operation following the North Strand Bombings . He maintained his trade union involvement and was a representative of fitters in Dublin Port, with his son also being active. William Halpin died in 1951.

Brothers in arms .

As detailed earlier,Williams’s two brothers took a different path, joining the British Army during World War One. Both survived, though James was shell shocked, gassed and unable to speak for a considerable time.

Cecil went on to join the Free State Army in 1922. However, he deserted after a short time. He was enraged by taunts of “taking the King’s Shilling” and particularly by what he saw as the disrespect shown for those who fell on the battle fields of Europe, many whose deaths he would have witnessed.

Cecil, accompanied by James, “called out” some men he felt had showed this disrespect in a city centre pub and ended up brawling with them. This left both as marked men which led to Cecil’s desertion and him taking the boat to England. James stayed and was prepared to challenge those involved. It is likely that William used his own position and good standing in the Republican movement to protect both his brothers, and Cecil eventually returned to the City.

Cecil became a professional entertainer, specialising in song and dance routines. When work became scarce in Dublin he again moved to England. Here he pursued his entertainment career and eventually became a bit player in the British film industry. The wonderful picture below shows Cecil, on left , with Jean Kent in the 1949 “Trottie True”. Also known under the title “The Gay Lady”, two future screen legends Roger Moore and Christopher Lee had early roles in this comedy/musical.

Cecil died in England in the early 1960’s, while James died in 1975.

Cecil Halpin (left) with “The Gay Lady” in 1949

image- Halpin Family / Rootschat

“There’s a uniform that’s hanging…”

The house on Valentine Terrace remained in the Halpin family until the late 1960′s. At that time its current resident Lar ‘Lagger’ Redmond moved in. Lar remembers shortly afterwards he found a Citizen Army Uniform and military belt behind a dresser. According to Lar “the uniform was all threadbare, but the belt was in perfect condition”. He also commented on the flag-pole attached to the front of the house, “It was about 10 foot tall” that a tri-colour used to fly from. As far as Lar remembers, Valentine Terrace was officially renamed as part of West Road sometime in the 1970′s. William’s Grandson, Colm Halpin lived in St. Mary’s Court, Church Road for many years , and was an active socialist until his death in May of 2016.

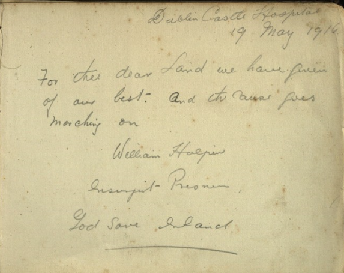

We will leave the last word to William Halpin himself , who on 19th May 1916 wrote from the Dublin Castle Hospital :

“To thee dear land we have given our best and the cause goes marching on.”

Sources:

There is no first-hand narrative by William Halpin of his activities available to us. Histories put on record by Frank Robbins and Thomas Leahy, fellow Citizen Army members and Dublin Dockyard workers, were invaluable.

In relation to City Hall garrison, we used an official state record of the rising (compiled in 1945), and the eye witness accounts of participants including Helena Molony, Kathleen Lynn and William Oman, all of the ICA. Groundbreaking and extensive research into this garrison has been carried out by Hugo McGuinness and the East Wall History Group.

Photos of City Hall rooftop and surrounds courtesy Hugo McGuinness .

Details of William Halpins Civil War and ARP service, plus later photo, were provided by Hugo McGuinness.

For non-military background,we drew on the extensive and fascinating genealogical research undertaken by the extended Halpin family. We also interviewed Williams Grandson, and East Wall resident, Colm Halpin. The 1901 and 1911 census were also consulted, as was the St Josephs school archive.

(Like much of our local history research, this project should be considered as a ‘work in progress’. Any further information, corrections or clarifications would be most welcome. Further information on East Wall/North Wall/North Strand Citizen Army members is being compiled. Also, any assistance or suggestions for other topics we should cover will be gratefully received.)

Contact: eastwallhistory@