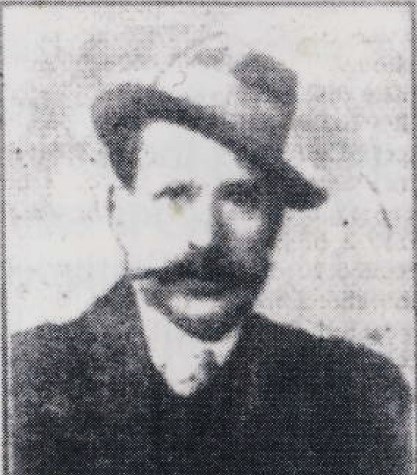

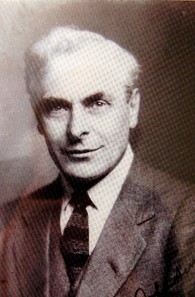

“One of the cheeriest men in the ward, and one of the most particular as to the set of his hair.”

Michael O’Doherty

During the 1916 Rebellion Michael O’Doherty of the Irish Citizen Army was wounded 12 times – 1 bullet hit his right eye; 2 his left arm; 1 his left jaw; 1 the left side of his head; 4 in his right arm; 1 in his right cheek; and 2 in his left arm . Despite his catastrophic injuries he survived, only to pass away just over three years later due his injuries and subsequent treatment. But the story of Michael O’Doherty and his family, does not begin, or indeed end with these events. The family had a record of trade union and political activism in the Docks dating back to the 1890’s, and for years after Michael’s death his family battled to have his Easter Rising participation properly recognised. This is their story:

The O’Doherty’s wore their politics on their sleeves. At a time when it was rare for the Gaelic “O” or “Mac” to be used Michael O’Doherty (senior) used it proudly when he married Margaret McCann in Ballymoney, Co. Antrim, in 1877. Throughout his life he would fight off attempts by well meaning Parish Priests to anglicise his children’s names in the belief that it might give them some advantage in life. The Land question dominated local politics in Antrim throughout the 1870s and Ballymoney Town Hall was the center of activities hosting many meetings and events relating to tenants rights. The O’Dohertys were farming people but Michael senior received a good education and was trained as a Law Clerk. Family tradition suggests Michael senior was politically involved at this time and was probably engaged in agitation for tenants rights. Michael junior was born here in 1879 however it seems his parents had to follow the time honored emigration route and moved to Scotland shortly after his birth. Family lore suggests it may have been due to their political activities. Not surprisingly some thought he was born in the Scottish Industrial heartland of Glasgow. While it’s unclear exactly what Michael senior’s politics were at this time, one tradition being an involvement with the IRB, according to his daughter Lilly, Michael junior, through his father’s influence, was “associated with Republican activities from boyhood.”

By the mid-1880s the family were living in Ballybough at 19 Forster Terrace with Michael Senior working as a law clerk to support his growing family. By 1891 they had moved to Seville Place just as labour problems were about to break out in the Docklands. The Merchants Protection Association had erected steam winches on the docks which alarmed the corn porters who saw the machinery as putting many of their fellow workers out of a job. It soon became apparent that the MPA intended using the situation to change employment conditions, break the various unions who represented the workers, and employ free or non-unionized laborers at whatever rates they saw fit. The members of the MPA had combined with the British Shipping Federation to break the unions and had placed a Mr. Hunter of the Shipping Federation in charge of the unloading of all grain-ships. Hunter had imported laborers from Cork and Belfast who were non-union members and working below the agreed Dublin rates. In June the Dublin grain-workers went on strike with action quickly spreading to the carters and even the ships firemen. Soon over 800 men were out.

Merchants Warehousing , East Wall Road . Note DMP man on street (Photo: East Wall History Group)

Large numbers of police were drafted into the docklands to protect the MPA workers as they unloaded various ships cargoes. By the 8th July the Freeman’s Journal was predicting an “all out Labour War.” Soon the workers of The Grand Canal Company and Gas Workers Union had joined them in sympathy with various other trade societies in Dublin promising financial support. At a meeting of the Trades Council on the 8th July the President called on the men to take “an active part in the struggle” and make their presence felt on the quays. He also noted that while the men might not be paid “their wives and children would be kept with bread and butter in their mouths.” More Free Laborers had been drafted in with the Merchant’s Warehousing Company finding a plentiful supply of country agricultural workers while one Belfast Merchant shipped in his own hands to unload his cargo. While the various speakers called for peaceful protests on the docks, P.A. Tyrrell of the Amalgamated Engineers Society reminded them, that “any man who helped the Merchants in this fight, no matter to what trade he belonged, whether he belonged to his trade or not, was a scab of an unmistakable type, and the name would never leave him.”

Two days later Charles M’Keever, a corn porter working for the corn merchants Brown and Gilmer, was driving a cart down Seville Place accompanied by a number of Shipping Federation employees. E. Donnelly, the corn porters union representative, lived at No. 50, and large crowds of women, children, and striking workers congregated outside his house. Noticing M’Keever the crowd began to chant “Scab!”, and throw stones and other missiles at him. Watching nearby was Michael O’Doherty senior, who given his occupation and what was about to happen, was possibly giving legal advice to Donnelly in relation to the strike. M’Keever went to his lodgings to find the windows smashed and the landlady promptly asked him to leave her house. At this point he was assaulted, kicked to the ground, and cut on the hands a number of times with a knife. The crowd then turned on Cahill and Storey, the Shipping Federation men, who subsequently left Dublin and returned to the countryside.

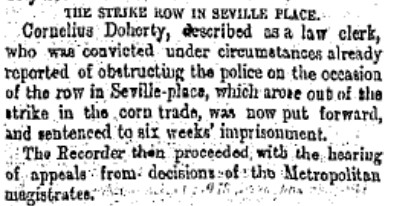

Of the two hundred people involved in the incident, only one, Michael O’Doherty senior, was arrested and indicted for assault with grievous bodily harm of the three men and Constable 109C who attempted to break up the row. M’Keever admitted to having previously seen O’Doherty on a number of occasions, suggesting he was engaged in organising the workers, and which might explain why he was singled out. Several witnesses claimed O’Doherty “took no part” in the affair and ultimately he was acquitted of the assault but was then charged with obstructing the Police in their duty. O’Doherty was sentenced to six week in jail.

The strike ended later that month but flared up again in August. As financial support fell away things reached an inevitable conclusion by mid-November when the strikers conceded the right of the MPA to use steam winches to unload cargos; they agreed to work with whoever the MPA chose to employ whether Free Labourers or otherwise; they agreed to a pay-freeze for at least twelve months. They also accepted that they would be re-employed at the discretion of their employers many of whom were intent on fulfilling the engagements of their imported workers. Facing financial ruin their Trade Union collapsed. The jail sentence seriously effected Michael senior’s health and by the turn of the century much of the burden of supporting the family fell on Michael junior. The British shipping Federation was invited to set up offices in Dublin.

The family moved to No. 10 Mayor Street just as a revival of Gaelic Games was taking place. Michael junior seems to have taken a great interest in the sport but it would appear his role was as more of an organiser than as a player. By 1895 teams such as Rovers (Sheriff Street), Charleville (North Strand), Hawthorns (East Wall) and Saint Laurence O’Toole’s were all making names for themselves in the local leagues. Michael Junior was coming into contact with people like James Nowlan and Dan McCarthy who would become life-long friends, the latter, the first Dublin born President of the GAA, fought in the 1916 Rising, and served as a Sinn Fein TD between 1920 – ’24. O’Toole’s in particular were deeply nationalistic with 51 members of the Club taking part in the Rising. They shared headquarters with the local Gaelic League Branch at 100 Seville Place, and their pipe band had Tom Clarke as it’s president and Sean O’Casey as it’s secretary. O’Doherty’s younger brother Patrick Joseph shared his enthusiasm, so much so, that a spur of the moment decision in May 1905 would have serious repercussions. Patrick Joseph was working as a Docker when on the 14th May 1905 he was unloading goods at the London and North Western Railways warehouse at the North Wall with a neighbor, James O’Reilly from Spencer Street. O’Reilly worked for the company, and examining the inventory, mentioned that there was a consignment of football bladders in the warehouse. They liberated three of them unaware that their actions were noticed by a Detective employed by the railway company. Both received 14 days in Kilmainham for their efforts.

St Laurence O’Tooles Pipe Band (including Tom Clarke)

Michael O’Doherty worked for Wordies an extensive carriage and storage company with premises in Beresford Place and East Wall in Dublin. They also had numerous branches throughout the country. Initially he worked in their warehouse and later transferred to the carters section earning £2.10.0 per week much of which went to supporting the family as his fathers health deteriorated. He took a keen interest in politics, both he and his father being on the electoral rolls for the North Dock Ward, when few had the property qualifications necessary. A revolution was on the way in Ireland and O’Doherty, as his Irish Citizen Army (ICA) colleagues would record, did “not shirk his duty when it came to the test.” 1908 saw the entry of James Larkin into Irish Labour affairs. Initially representing the British NDLU, Larkin had arrived like a whirlwind, agitated on behalf of Irish workers, and quickly found that his union had little interest in their Irish members problems. Suspended by the British Executive, Larkin went on to found his own Irish union on the 29th December that year. One of the first members of the No 1 Branch of the ITGWU was Michael O’Doherty junior.

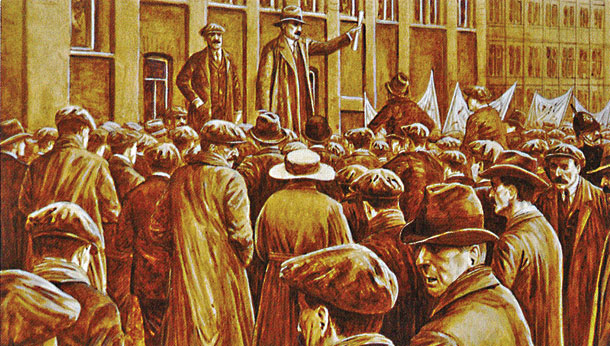

By 1910, Michael’s younger brother Constantine, having completed his apprenticeship as a pork butcher, had set up in business in Belfast with his young family. Michael is recorded in the 1911 census as living there in his younger brother’s house in Salina Street a short distance from the Belfast branch of Wordies at Divis Street. At first glance it seems a strange move. Ellet Elmes, a protestant and O’Doherty’s future colleague in the Citizen Army, moved to Belfast at much the same time to work in Harland and Wolfe shipyard. Elmes found the deep-rooted sectarianism too difficult to stomach and returned fairly quickly to Dublin. Most dockworkers in Belfast were members of the British NDLU. However, in 1910 P.T. Daly had brought members of the Belfast deep-sea dockers into the ITGWU. In May 1911 James Connolly arrived in Belfast as Branch Secretary and Ulster Organizer setting up union offices at 112 Corporation Street. By July 1911 he had 300 dockers out on strike in sympathy with the Seamen and Firemen’s Union. Nightly meetings were held on the steps of Belfast Customs House on one occasion organizing a demonstration using a coffin inscribed with “Shipping Federation” which were attempting to break the strike. The strike turned nasty but eventually the employers offered to recognize the ITGWU and offer an increase of 1 shilling a day. It seems likely that Michael O’Doherty with his skill at organizing and his Ulster background was one of a number of activists such as Ellet Elmes sent up to assist Connolly to establish the union in Belfast.

James Connolly in Belfast ( Illustration: Sean O’Brogain )

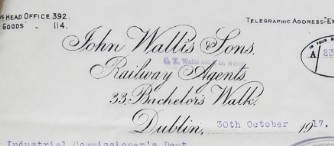

O’Doherty was back in Dublin by 1913. On the 31st July he led over 300 workers from Wordies out in sympathy with the great strike then in progress. Information obtained by the National Graves Association stated that he “took an active part in the 1913 Lockout“, while Jim Larkin called him one “of the fighting old guard of the Transport Union.” Labour News in 1936 recalled that on the formation of the Citizen Army O’Doherty joined up to “defend the workers from the batons of the police during the great lockout.” The strike cost him his job but he quickly found employment at Wallis & Co who described him as a “sober, industrious, and willing worker.“ He continued to throw himself into Citizen army business.

Michael O’Doherty spent most of April 1916 on guard duty at Liberty Hall in preparation for the Rising. On the 24th April he was part of the group which marched from there, under Michael Mallin, to Stephens Green. He was one of a party of four who raised the Tricolor flag above the roof of the college and as he was a good shot, O’Doherty remained on the roof of the College of Surgeons tasked with operating as a sniper if they came under attack. ICA man James O’Shea was also placed on the roof on Tuesday 25th April when the British attack was launched from the Shelbourne Hotel. He recalled it as “hot and heavy” being “unable to stand up under any circumstances.” Bullets chipped away at the masonry and O’Shea was impressed by the ability of the opposing marksman. He had emptied his clip and was about to reload when a colleague tapped him on the shoulder and pointed to a figure on the right. There was Michael O’Doherty casually eating a sandwich as if he were on a picnic. O’Shea tried to shout at him to take cover but before he got the words out he saw the bullets from a machine gun burst rip into O’Doherty and as O’Shea remember it “his face was gone”. Countess Markievicz described him as being “deluged with shrapnel.” As O’Doherty slumped over the parapet of the roof blood flowed onto a white blanket below shocking and freezing his comrades. Joe Connolly, a future Fire Chief of Dublin, bravely raced from the green across to the college and up onto the roof. Together with David O’Leary, who had come over from London for the Rising, they managed to bring O’Doherty down before he could be hit again.

Madeline fFrench Mullen was there when he was lowered and described his as being in “a mangled condition.” It was probably because of Joe Connolly, a serving fireman as well as a member of the ICA, that the Fire Brigade ambulance came for O’Doherty just after midnight and brought him the short distance to Mercer’s Hospital. Two hours later they had to retreat in their attempts to take the body of James Corcoran from the green due to the continuous crossfire. It almost certainly saved O’Doherty’s life. Frank Robbins who opened the door for the crew taking O’Doherty out on a stretcher, noticing the amount of blood he has lost, whispered “you’re a gonner and the Lord have mercy on you.”

Location on roof of College of Surgeons where Michael was shot.

O’Doherty had been wounded 12 times. 1 bullet hit his right eye; 2 his left arm; 1 his left jaw; 1 the left side of his head; 4 in his right arm; 1 in his right cheek; and 2 in his left arm. After 4 days he was arrested at Mercers and taken to the hospital at Dublin Castle. A VAD nurse who treated O’Doherty, having heard “half his face was gone” and looking at his blood soaked bandages, prayed constantly that he might die to relieve his suffering. However a week later, she found out that his “face though frightfully disfigured, had not been blown away” and having made a recovery, she wrote that he became “one of the cheeriest men in the ward, and one of the most particular as to the set of his hair.” O’Doherty was in a bed next to Cathal Brugha who had been shot over 25 times so they had much in common. Another of their nurses held a commission in the UVF and was forthright in what her “boys” would have done to the Rebels had they got the chance. Yet when medical attention was needed she was a thorough professional impressing the Citizen Army and Volunteer patients with her kindness, attention, and skill. In an autograph album collected by a visitor to the Hospital, O’Doherty wrote “sure the great God never planned, for slumbering slaves a house so grand” in recognition of his treatment by the British army medical staff. He also noted that despite his horrific injuries he was “still not downhearted.” One day a soldier of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers came into their ward and putting a bag of fruit on Brugha’s bed, said “thanks!”, then turned around and walked out, to all the patients astonishment.

Under guard at Dublin Castle hospital (ICA men , group does not include O’Doherty)

After three months in hospital Michael was sent to Knutsford Prison and later the detention camp at Frongoch. He’d lost an eye and an ear and the use of his left hand. The military guards at Frongoch tried to make fun of O’Doherty’s disfigurement. His reply was “see that eye and this hand – while I have one eye and one hand to fight with, no one will ever stop me fighting for Ireland.” Released from Frongoch in December 1916 O’Doherty initially rejoined his ICA colleagues. Kathleen Lynn organised to have him fitted with a glass eye but according to Countess Markievicz “the hardships and unsanitary conditions of the camp were more that his shattered body could resist and he just grew thinner and weaker.” O’Doherty made light of it and rarely complained. He was unable to work because of his disability and by 1918 had vanished from both Labour and ICA circles. Things were moving fast and according to Markievicz “in the rush of events no one had taken the time to find out where he was or what he was doing.” He was dieing, “dieing slowly from the effects of his treatment at the enemy’s hands”

O’Doherty passed away on the 22nd December 1919. His funeral was large and Countess Markievicz who attended has left a moving record of the events.

“So we his comrades in the fight, gathered to pay our last tribute and respect to a brave soldier and a loyal comrade. He lay so thin and tall in his brown habit with the crucifix in his curled hands and we thought how it softened death for him and for us all. … The atmosphere in the little house was electric with one thought, that he who lay there was true to Ireland, you heard it on every lip. His old mother sobbed out how Mickey had died a true martyr for Ireland, but how sorry he was to go before the fight was over and soon, sisters, brothers, friends, all paid the same tribute. He was a true Irish soldier and to Ireland he had given his life.

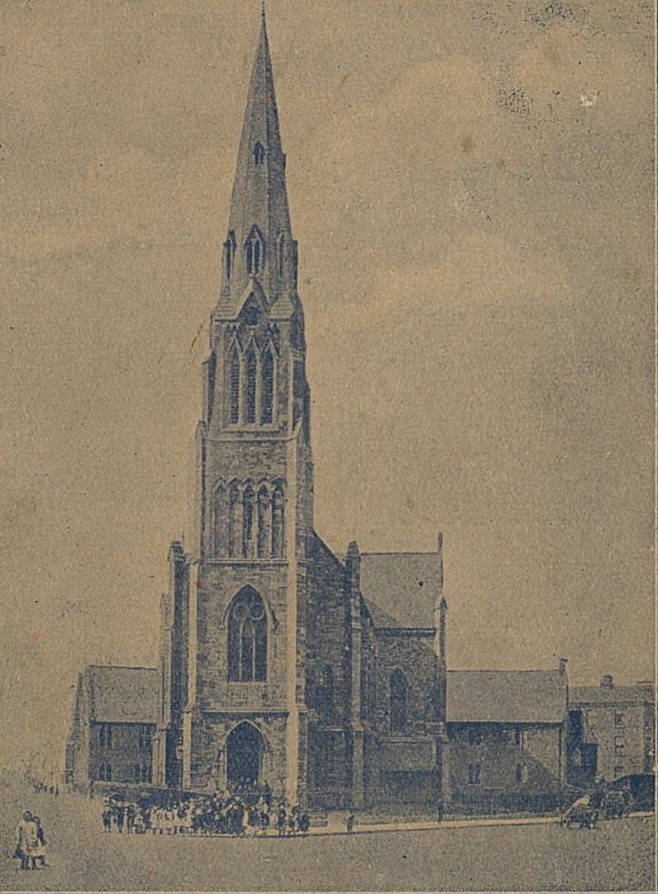

After a while his comrades placed him in the coffin and it was borne to Saint Laurence O’Toole’s Church as he would have wished, his soldier comrades marching behind him, taking turns to carry the coffin on their shoulders. His coffin was covered in the tricolor flag that he loved and under which he fought; behind him marched a piper playing an Irish hero’s funeral march on the bagpipes and … marching in military order were the Irish Citizen Army guarding him. He went to his last rest in the way he would have wished, a soldiers way, in spite of England’s armies, her tanks, and her machine guns.”

St Laurence O’Tooles , Seville Place (Photo: East Wall History Group)

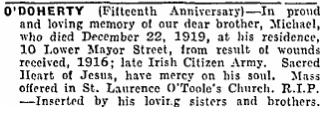

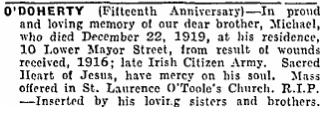

In the death notice placed in the Freemans Journal on the 23rd December 1919 Michael is described as “Irish citizen Army 1916.” For nearly two decades afterwards the family placed memorial notices in the papers on his anniversary which recorded his role during Easter Week. However, according to the family a well-meaning Doctor Dolan from Amiens Street, who treated Michael before his death, anxious that they should avoid any repercussions from the British military, had given the cause of death as stomach cancer. On 29th November 1919, Johnny Barton, the notorious Detective Sergeant of G Division, of the DMP, had been shot dead by The Squad. An attempted ambush on Sir John French, Lord Lieutenant and Chief of the army in Ireland had been carried out near Ashtown on the 19th December. According to family tradition the DMP made several visits to the O’Doherty home at this time and it was believed that their house was being watched. O’Doherty’s ICA comrades called on the family to have a military style funeral, such as had been given to ICA Stephen’s Green veterans Bernard Courtney in March 1917 and John Byrne in June 1918. Both had been large spectaculars, Courtney’s funeral touring the sites of the city where he had fought while Byrne’s consisted of four companies of the ICA marching from St Laurence O’Toole’s Church to Glasnevin. Lilly O’Doherty claimed that they were anxious “for the safety of the poor boys and did not wish to have any publicity” as times were “far from quiet.” Doctor Dolan, in keeping with the families wishes, had, according to Lily, left gunshot wounds off the death certificate. It was also for this reason that Michael was buried in the family plot at Glasnevin rather than in the Republican Plot as many of his comrades wished.

With the advent of the 1923 Pensions Act Michael senior applied on behalf of the family for a pension in recognition of his sons service . In doing so he had been upfront in admitting that the Irish National Aid Association had given them a grant in 1917 of £400 in acknowledgement that he “was the sole support of his family.” At that time Dr. Matthew Russell, who examined Michael, claimed that the wounds were so severe that he would be disabled for life. They also admitted that part of the aid money left to Joseph, Michael’s disabled younger brother, had been used to buy a grocers shop at No. 1 Mayor Street. The application was rejected on the basis that death happened outside the three years limit laid down under the 1923 Military Service Pensions Act. The family made appeals, to no avail, however by 1924 questions were being asked the result of which was an extension of the period of death allowed from three to four years after being injured which brought Michael O’Doherty’s case within the remit of the amended act in 1927. Once more Michael O’Doherty applied and again he was rejected on the basis of the death certificate provided by Dr. Dolan. The official verdict given on the 28th February 1928 was “your son’s death was not attributed to service.”

The O’Doherty family opposed the Treaty and according to tradition a number of Michael’s sisters were in Cumann na mBan. On the 1st November 1923 Michael senior was in the shop at No. 1 Mayor Street when he saw 6 men walking to his houses at No. 10. Following them he found their leader, a former CID man named William Kean inside the house threatening his son Joseph. Michael identified himself and then he asked them if they were CID and what their authority was. Keane produced a pistol and stated that it was his authority and “if you don’t shut up I’ll put the contents into you.” It appears they were looking for someone they believed was in the house but not finding him they left. Michael followed them to Guild Street where he found a policeman and gave their descriptions. They were arrested a short time later. However at the trial Kean produced a number of good character witnesses who testified to his excellent service with both the CID and Protection Corps and seems to have won over the jury with a case of mistaken identity. He was found not guilty of intimidation. It’s difficult to assess just how much incidents such as this may have affected the family’s quest for recognition of Michael junior but it may well have been hovering in the background of their numerous pension applications on behalf of their brother. This incident certainly suggests that they may have been active on the anti-treaty side and that their home may have been used as a safe-house for activists on the run.

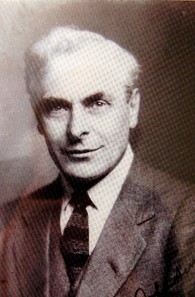

Thomas Johnson , Labour Senator.

The fight for recognition of Michael O’Doherty’s service took a heavy toll on the family. Joseph, who had never had good health, died on 26th November 1924. Margaret, Michael’s mother, who, according to Lily had never recovered from her son’s death, died on 16th August 1926. The house at No. 10 Mayor Street was sold that year. Michael Senior, finally worn down by all his efforts, died on 19th January 1932. Lilly O’Doherty now took up the fight. In an intervention on her behalf by Labour Senator Thomas Johnson, it was stated that despite whatever the “formal documents” might say, that “there is not the smallest doubt that he died from wounds received as a soldier of the Irish Citizen Army on active service during Easter Week 1916.” Matters were further complicated by the fact that Dr. Dolan who had treated O’Doherty, was now dead. While there was a willingness to understand that this was a special case, under the terms of the act, only a dependent under 21, or who was an invalid, could benefit, and as Lily, the latest member of the family to apply, was neither, her case was again rejected. Theresa O’Doherty, who had suffered from spinal troubles from 10 years of age next applied. According to her Dr. Dolan had only examined Michael once the day before he died and wouldn’t have been in a position to diagnose cancer of any kind from that examination. In her supporting evidence, the Rev. Canon Flood, former Parish Priest of St Lawrence O’Toole’s stated that O’Doherty was so badly wounded, that “his living so long was considered almost a miracle.” The O’Doherty’s would continue to fight for recognition of Michael up to 1961 with the authorities continually claiming that his death had not been caused by wounds received in Easter week or a disease caused by Military Service.

George Plunkett at unveiling 1936.

What recognition the family did receive finally came through the National Graves Association in 1936. In November that year the NGA unveiled gravestones to Sean Healy, Dan Murray, and Michael O’Doherty at Glasnevin. In keeping with the times, while the gravestones were unveiled by George Plunkett, the actual speeches or graveyard orations had to be held in nearby DeCourcy Square as it was seen as a political event. The rules of Glasnevin prohibited political speeches at Funerals.

The final fight for the O’Doherty’s came in 1973. At that stage the three remaining sisters had a shop at Summerhill Parade over which they lived. A number of local residents still remember them with great warmth and affection. Shortly after 11.00pm on Sunday 1st January 1973 a number of young men who had been drinking nearby decided to break into the shop to get more drinking money. Alarmed at the noise the sisters decided to defend themselves. It was probably not the wisest course of action but given their background and history it seems unlikely that they could have chosen to act differently. Kathleen, then aged 73 was badly beaten and cut around the eyes and face, while Theresa, then 75, had her leg broken during the assault. Lily, by then an invalid, had to be treated for shock. There was a total of £10 in the till. Lily died on the 1st January 1974.

“The Fighting Old Guard” : Michael O’Doherty at ICA parade

Our thanks to Con O’Doherty for assistance with Family background and traditions. Jimmy Wren for assistance with the history of the GAA in the North Dock area. The Irish Military Archives, The National Archives, National Library, and Dublin City Archives for material in their care used in this piece.

For clarifications, corrections or further information please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com