Bloody Sunday 1920, the G.A.A. and “Stonewall” Jack O’Reilly

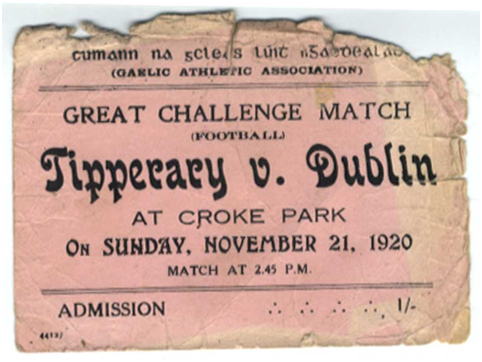

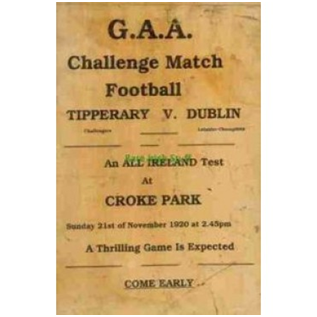

November 21st 1920 will be forever remembered in Dublin as Bloody Sunday. The events of that day were to lead to 31 deaths in the City, and are amongst the most notorious incidents of the era. In a co-ordinated series of early morning attacks the I.R.A. targeted a number of individuals attached to British Military intelligence operations, shooting dead 14 men. Later that day, in a retaliatory attack, British forces opened fire on the crowd at a football match in Croke Park, resulting in 14 deaths – one player, Michael Hogan, and 13 supporters. Three prisoners, unconnected with that day’s events, were afterwards shot dead in the guardroom at Dublin Castle, with a claim they had attempted to escape later discredited. Two were IRA members, while one was an unfortunate civilian caught up in a British army round-up.

The match in Croke Park that tragic Sunday was a challenge match between Dublin and Tipperary. The Dublin team featured a large number of players from the Laurence O’Toole team, based in Seville Place, which would have been our local team. This included “Stonewall” Jack O’Reilly, from number 2 Mayor Street. His sweet-heart (and future wife) Brigid Smith was a spectator, and was also caught up in the attack.

The East Wall History group recently had the privilege of talking to their son, Jack O’Reilly who still lives in the family home in Mayor Street. Jack told us about his parents experience on the day, other incidents that occurred during this period and also about his father’s legendary football career and others on the great Laurence O’Tooles team of this era.

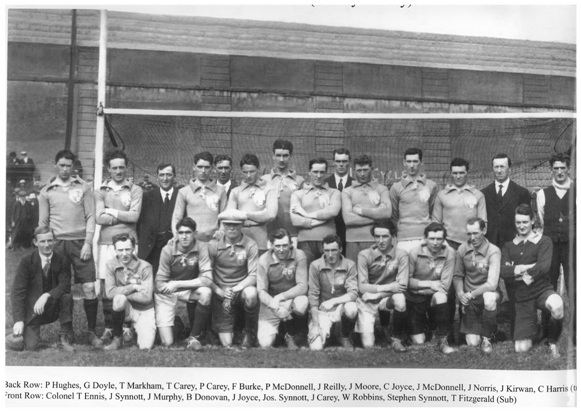

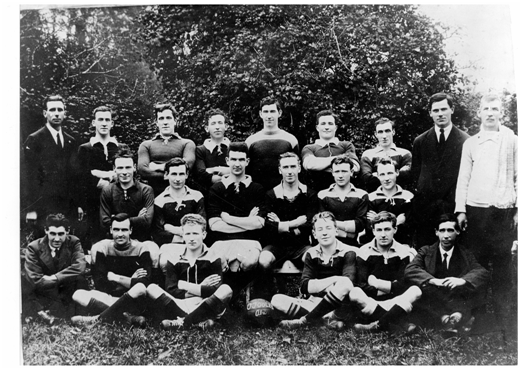

The Dublin Team on Bloody Sunday

Jack started off by telling us why so many local players were on the Dublin team that day:

“That was our local team, O’Tooles, they used to win the Dublin championship year after year, in those days the team that won the championship picked the Dublin team, there was no such thing as selection or anything, the team that won it picked the county team, so that’s why there’s so many of those players there on the Dublin team .You know, I’d say there’s about 8 or 9 of them on the Dublin team.”

He then recalled who some of these men were:

“That’s the father there, Jack O’Reilly. There’s Paddy McDonald and Johnny McDonald two brothers, I’m not sure where they lived, it could have been Seville place, I’m not sure .There’s John Synnott, Josie Synnott and Stephen Synnott. They were all local too.90% of them were, all O’Tooles. John Synnott was the man, on that particular day, when all the shooting started, he was up the other end of Croke Park, and he jumped over the wall, swam across the canal and back home down towards Seville Place. Josie, he was the coal man, I don’t know what Stephen worked at. There’s Joe Norris, he was a great friend of my fathers. Tom Carey… There’s Paddy Carey, he mustn’t have been playing that day, but he was there, he was a regular on the Dublin team. I’d know a few of the others. That man there was Joe Joyce, he played for Parnell’s, the team out in Donnycarney. There’s Charlie Harris the trainer, he also trained the Irish soccer team, and he also trained Bohemians as well. There’s another little man…Billy Robbins was his name, he worked down in the Pigeon House… he was another O’Tooles man.”

Brigid Smith, Alice Doran and _?_ Ryan

“There’s going to be trouble up there…”

Jack identified the three young women in the photo:

“There’s a picture of the mother and her two pals. That’s my mother, she was only in her teens there. She wasn’t married at that time, she was only going with the father. That was her friend Alice Doran, they lived around on

He then detailed their experiences in Croke Park on Bloody Sunday:

“Now, to put it in context with what happened on Bloody Sunday …On the morning of the match, on bloody Sunday, the massacre in mount street, when all the British secret service guys were all killed, shot in their beds, well the British were full sure… you see that match that day was between Tipperary and Dublin, and the British were firmly convinced that it was the Tipperary crowd that were after doing it, that business in Mount Street, which they didn’t, but they were fully convinced of it. But anyway, the father knew about it, naturally they heard about it. And he told the mother “You don’t go up to Croke Park today, there’s going to be trouble up there.” … My Mother often told me “ah sure you know the men …you know the men, the way they didn’t want their women there.” So anyway, the three of them went up to Croke Park and they sat on the side-lines, there used to be seats, a little bit away from the grass, and they sat there. The mother said the one thing she remembered about it, just before the ball was thrown in, an aeroplane appeared, you know as if that was a signal for something, just hovered around and disappeared. Anyway, the match started, and I don’t think it was even on ten minutes and then the black and tans came into CrokePark, and started shooting indiscriminately, you know. And they had to duck down on the sideline. That man from Tipperary, he was unfortunate, that man Hogan, he was actually playing that day on the Tipperary team, he was shot. He was the only one player that was shot. They were firing indiscriminately, and apart from that man Hogan there were 13 civilians killed, and some young lads amongst them.”

After the shooting stopped, the ordeal was not over for everybody:

“Anyway, the Mother was telling me, when the shooting died down, they let the women out … but my father told her what happened afterwards. They rounded up the players in the dressing room and they wouldn’t let them out. In fact they were half convinced that some of them were involved in the shooting that morning. I told you about John Synnott, what he did – John ran down the far end of Croke Park , jumped over the back wall , that’s what we’d call the canal end, and swam across the canal and came home then, to Seville Place. I think they let the players out at 8 o’clock that night, they’d kept them in the dressing room all day. A lot of the Tipperary players I heard stayed in houses in Seville Place, up near the Five Lamps, because it was near where O’Tooles had their club, 100 Seville Place. They stayed there overnight.”

The aftermath: anniversary matches , Frank Teeling and Vinnie Byrne

An anniversary challenge match took place in subsequent years:

“After that, every 21st November, that was the anniversary, they used to always have a challenge match with Tipperary and Dublin in Croke Park. They used to gather around the spot where the chap was shot, and they used to have a little ceremony, they’d say the rosary. But, as you can well imagine, year after year, the survivors got smaller, they were dying away, including my own father, he died very young, he was only 45. And gradually, the survivors all went, and that put an end to the ceremony.”

Jack vividly remembered some of the Bloody Sunday events being discussed years later:

“They never really did find out who did the shooting, in Mount Street, that Morning. I saw a man on television years afterwards, about 50 years later, he said he was one of the Dublin Brigade that did the shooting. He was real cool, it’ll tell you what it was like at that time… (the interviewer) asked him, did you feel anything , no he said, I just went in and plugged them. Of course it was dog eat dog that time.”

(This was the now famous interview with Vinnie Byrne, a member of Michael Collins Squad. Interestingly, Vinnie Byrne kept a scrapbook throughout his life, which included the a photograph of the Dublin team, including Jack O’Reilly)

The massacre at Croke Park was not the only impact that the events of Bloody Sunday were to have on Brigid Smith and their family, which would continue to affect them for some time. During the I.R.A. Operations that morning, only one volunteer was actually captured, local man Frank Teeling . Having taken part in an attack at Lower Mount Street he was shot, wounded and taken prisoner by the British. He was sentenced to death, but early the next year he escaped. Jack takes up the story:

“Frank Teeling lived next door to where my mother lived, down in Wall Square, and they used to be down there every second night looking for Frank, because Frank was one of the guys that got out of the jail up at the park, Kilmainham Jail. He was one of the guys that got out the night before they were all shot. The black and tans used to be always around the place looking for him. He was on the run and avoided them all. But sometimes they’d come into my mother’s house, they’d be searching all the houses, it was just a little place, maybe 20 houses, it was just what it said Wall square. There was another night, there was an uncle of mine, that would be my mother’s brother, he was down in the house in Wall Square, that was the family home, and if they ever saw a man in the house they’d arrest him, and my uncle Mick , he hid when he heard them coming, he hid under the bed . And believe it or not he wasn’t discovered you know. So he got away with it that night.”

Love in a battlefield

Wall Square and Jane Place, where Frank lived, were adjacent, and located just off Oriel Street, as explained below. The O’Reilly family home in Mayor Street was in sight of the back of the LNWR Rail Hotel on North Wall Quay (better better known as “the British Rail” or simply “the red building”). During the early 1920′s this was occupied by British Auxiliaries, and a regular target for I.R.A. attacks:

“The Hotel building there, when they had the searchlights on, there were often skirmishes with the I.R.A. and them, and they’d be firing down and all from the hotel. As far as I know nobody around here was killed in that incident. They always kept it, the British soldiers were always there, ’til the thing ended.”

While fortunately nobody was killed, no doubt local people were cautious and aware of the dangers. Not all acted accordingly though, such as Jacks father, who when it came to risking life and limb under military rule was what could best be described as “a fool for love”:

“…you know the hotel down here, the red building, the British used to occupy that, and they had the searchlights going across the bridge. My mother lived down in Wall Square, down the end of Oriel Street… (there at Gerry Fay’s shop)… the very end, beside Jane Place it was. That’s where my mother lived, in Wall Square. So when the father would be down there at night, he had to come back down Seville place, across the bridge down to here, but he used to have to crawl on his hands and knees so the railway wall would protect him so the floodlights wouldn’t catch him, if the floodlights caught him, that was it, they’d just arrest him. There was a curfew then.”

“They didn’t like them…”

Jack also talked about the attitude of locals to the British forces:

“They didn’t like them. Not so much the soldiers, as the Black and Tans, they were the number one enemy, the black and tans, cos if they caught you, that was the end of you. You had some hope with the soldiers you know, maybe they’d march you off to jail but not with the black and tans. That’s who they really hated, the people around here, the Black and Tans.”

And what did his mother think of local men who joined the British army:

“She used to give out sometimes – she’d say they joined the British Army under false pretences…they thought they were going off to fight for small nations… (laughs)… of which we were one you know. But then the British turned it around on them. The thing was mixed, there was always mixed feelings about that.”

There was also an understanding of the circumstances that led to some men enlisting

“A lot of them for economic reasons, just for the money… not many of them lived to collect it. That First World War, they were just cannon fodder.”

“The ordinary Jersey didn’t fit him…”

Having discussed these incidents that occurred during the revolutionary period, Jack spoke at length about his father’s football career, his All Ireland successes, his nick name and how the boys of the family didn’t follow in his footsteps.

“Stone Wall” Jack O’Reilly played in a number of All Ireland Finals, and was part of the team that won the legendary three in a row:

“They won the three, 1921,’22 and ’23.They won the three all Irelands and he was on them teams…. But then, when they’d win the all- Ireland do you know what the big celebration would be… my mother used to weep when she’d see them teams getting sent to New York and getting entertained in the big hotels… they’d walk down from Croke Park , down to 100 Seville place and there’d be a ceili there that night. ..(laughs)… That was it, that’d be the celebration.”

“He didn’t play that long afterwards, up until 1927, he retired. He got too heavy. You can see him in the pictures. He always had a different jersey, ‘cos the ordinary Jersey wouldn’t fit him. He had massive, massive shoulders, and you can see in the O’Tooles picture he had his own jersey. We had that for years, I used to wear that when I was at school ,playing for O Tooles , when I was a kid, and I’d put the jersey on it’d be down to my ankles (laughs) . I thought I was great, putting it on.”

Jack wearing his “own jersey”

“Frank Cahill was a gentleman…”

Jack recalled his school days, where his teacher was Frank Cahill, a name synonymous with St. Laurence O’Tooles and the G.A.A.

“The local school teacher, Frank Cahill… he started the primary schools football… He was our teacher for years. When we made our communion we’d go up the Christian brothers. We were all terrified, we thought we were going to be killed like, you know. Lucky enough, Frank Cahill … he was still teaching there …those teachers in those days had an awful reputations, Frank Cahill was a gentleman he was …There’s a plaque to him, at the Church, at the side. I think it was in 1957 he died.”

Frank Cahill was aware of the family connection:

“And of course he’d be asking the names, and he asked me my name and I told him, and he said “Do you know I taught your father”, which was true enough you know. He was a very nice man. He was a gentleman”

The O’Reilly brothers did not follow in their father’s footsteps:

“I didn’t play that long. I played ’til I was about 23. Neither of us, either Matt or myself or the brother that’s in Melbourne, Paddy, none of us took after him for the football, and none of us took after him for the size. In those days the football was all what you call catch and kick , there was none of this fancy business of passing and all, and it was man for man, you marked the man beside you , which is completely different than the way the game is now.”

“She was a marvel…”

“Stonewall” Jack O’Reilly passed away in 1942:

“That was always my biggest regret, that he died so young. I’d have lovin’ to hear all the stories about the matches and all, when they were playing down the country especially. He died in 1942, he was only what, 45, that’s all.”

Brigid was widowed at a young age, left with 8 children .But according to Jack:

“I don’t know how she ever did it. She was a marvel you know. And she never complained, I never heard her complaining in her life.”

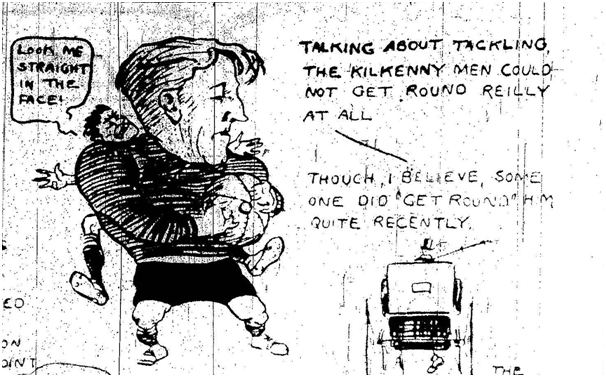

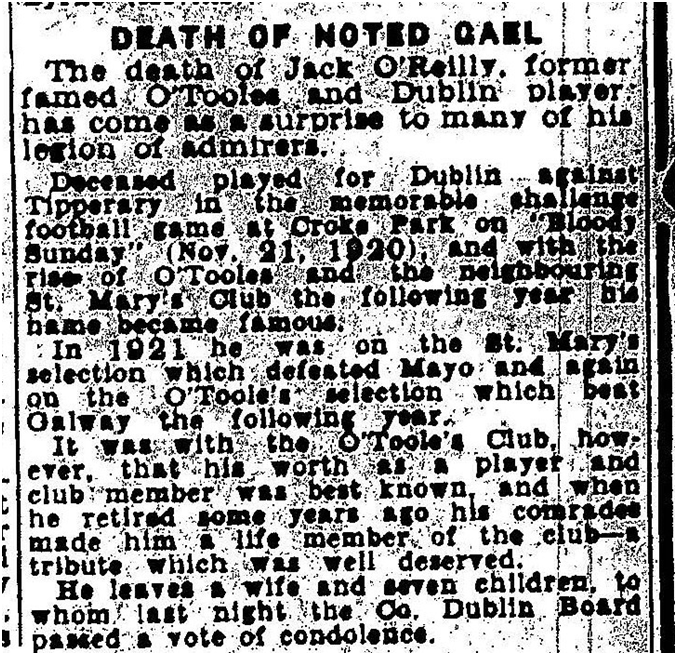

In his chat with the East Wall History Group, Jack also covered a number of other topics about his family and the local community. This includes his own working days , the value of education, the transport of lifestock through the street, travelling across on the Liffey Ferry and the memorable occasion when Gene Autry arrived in Dublin via North Wall and Mrs Bellew became the proud owner of a piece of his horses tail ! These are all stories for a future article. We will end with this wonderful newspaper clipping from 7th November 1922 (almost two years after Bloody Sunday) which captures the legend that was “Stonewall” Jack O’Reilly, shortly after his marriage to Brigid.

“We have an old paper, from that period, and there was a caricature of the father in the paper. Believe it or not they were playing Kilkenny, in football, which was extraordinary, Kilkenny was always hurling as you know … that particular match, they bet them, and they had a cartoon in the paper that said Kilkenny forwards have terrible trouble getting around stonewall jack, that’s what they used to call him, he used to play left half back… underneath it they showed , you know the old horse and cart years ago, they said though the Kilkenny forwards couldn’t get around him ,there was one person got around him , (laughs) that was the mother.”