“A very busy evening…not home until very late.”

On Thursday evening, the 8th June 1916, word spread among dockside workers that a very special republican prisoner was about to be deported. As the prisoner arrived on the quays a great cheer went up from the gathering crowd. The prisoner in question was Doctor Kathleen Lynn, chief medical officer of the Irish Citizen Army who had fought at the City Hall in the recent rebellion. For many of those cheering she was the kindly lady who had treated them and their children at Liberty Hall in 1913 during the dark days of the lockout. And afterwards, in August of 1915 she began instructing the ICA women’s sections Ambulance Corps. And it was not just the ‘transport union’ types that valued Lynn and her work. A correspondent , describing themselves as “A Loyalist and Unionist” writing of Lynn’s deportation in the Freemans Journal claimed that for many years she ran free clinics at The Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital and that Dublin “owes Dr. Lynn a great debt of gratitude.“ He went on to say that “as an honourable Christian lady … the present generation has seen few equals of Doctor Lynn, and no superiors.” It was known that Lynn never asked whether you had the money for treatment, only what the symptoms were. In fact it was said she never took a payment from the poor, so much so, that in 1917 Countess Markievicz remarked that “her paying patients must almost all be in the enemy camp!”

Maire Comerford of Cumann na mBan and a lifelong republican, remembered her as the embodiment of the line in the proclamation to “cherish all the children of the Nation equally.” She claimed that Lynn held that “every child was an individual and must know himself, or herself, loved.” Bill Oman of the ICA, many of whose 11 children were treated by Lynn said “to know her was to love her, and one had only to see her attend a sick baby to realise her great love of her profession.” Those who were treated by her remember her powerful diagnostic skills as she probed you with careful questions to discover your ailments. Phil Churchill, treated for TB by Kathleen Lynn, remembers it as if she stared right into your soul. With children, each answer would be responded to with calm all knowing “quite! quite!” Then as if to reassure you, Lynn would summon a second opinion by carefully taking your hand, and reading your lifeline, would confidently reassure you that everything was going to be fine.

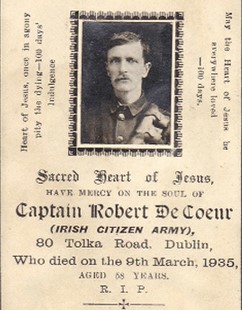

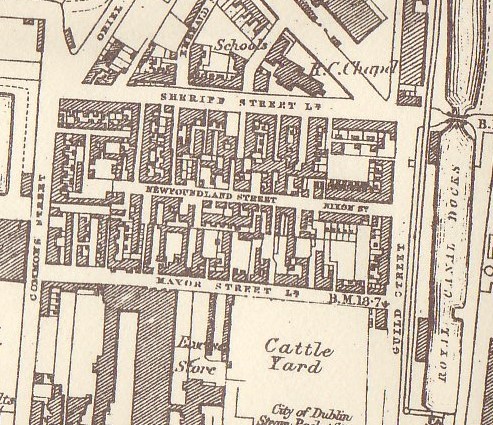

Lynn was a strong believer in the healing powers of good clean air. She commissioned the architect Michael Scott to build a balcony at her home on Belgrave Road, and throughout her life, on fine evenings, would sleep on the Balcony. When she discovered that former Sheriff Street and North Strand resident Bob DeCoeur, an officer in the Citizen Army, was suffering from Tuberculosis, she arranged for him to spend some time with her friend, Dr. Eleanor Fleury, at Manor Kilbride in Wicklow, which almost certainly prolonging his life by several years.

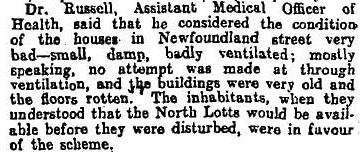

During the 1936 debates on clearing the inner city slums in Dublin Lynn argued that Flats should have “wide balconies where the perambulator can be put out, and the toddler take the air under his mother’s eye.” She further argued that the complexes should not take up the whole space, calling for communal playgrounds and gardens where “little ones could play in safety.” Many of these ideas were to be incorporated in the Charlemont Street development designed by Michael Scott for the Charlemont Public Utility Society in the 1940s although only one block, fFrench-Mullen House was built. (This was a project inspired to some degree by the initiatives of Canon DH Hall of St Barnabas Parish, who was responsible for significant progress in house building in the North Docks).

It was probably Lynn’s influence and championing of ‘fresh air’ which saw the Old Citizen Army Associations charity work include days out in the countryside for young inner city children. She had even extended this passion at one time to the treatment of TB patients at St. Ultans by placing sufferers of the disease on the hospital roof.

It was the same love of the outdoors that saw her leave the cottage at Glenmalure (given to her by Maude Gonne McBride) to An Oige in her will in 1955. It was later extended to accommodate 20 people in three dormitories, with a common room, kitchen, and modern lighting and heating. The children of ICA veterans Christy and Dina Crothers- Phil Churchill and Eilish Lynch recall visiting Lynn at Glenmalure as children.

Lynn’s Mayo background is believed to have introduced her to the healing powers of herbs and although a brilliant medical student she never lost her interest in the medicinal nature of plants. Interestingly, Bridget Dirrane, one of the first nurses employed at Saint Ultan’s in 1919 was an accomplished herbalist from the Arran Islands having learned that skill from her mother. A generation of children from Rathmines and beyond would remember with horror and embarrassment school lunchtimes consisting of parsley sandwiches while their classmates tucked into more substantial fare. For others it was the exotic healing powers of garlic and milk which was prescribed. The Crothers children still remember with horror Saturday morning excursions to Baggot Street and the only Italian shop in Dublin where this rare and disgusting tasting herb was to be found. However, in compensation, their Father also brought them to the little shop at Liberty Hall where Rosie Hackett could be relied on to provide free bars of chocolate as an antidote. Their mother, Dina Hunter from Irvine Terrace, had trained under Lynn in the ICA at Liberty Hall and also served alongside her at ‘The battle of Dublin’ in 1922. Their father Christy Crothers would lead the honour guard of ICA veterans at Lynn’s funeral in 1956.

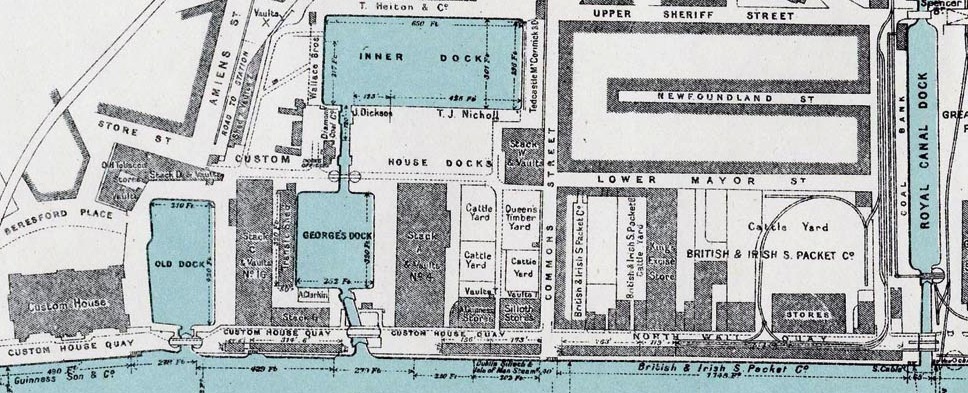

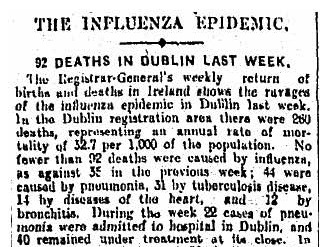

It was the same Rosie Hackett who remembered a “midnight mobilisation” of the members of the Irish Citizen Army in late 1918 for a special operation in Charlemont Street. Rosie got the call about 10.30pm and over the next hour and a half all who were called on came without hesitation because, according to Hackett, to obey Lynn’s command was “not a burden but a privilege.” Some months previously as the Flu Pandemic raged throughout Dublin, Lynn, released from her second deportation following the intercession of Dublin’s Lord Mayor, and armed with a large consignment of vaccine, had organised to inoculate the same Citizen Army members at Liberty Hall undoubtedly saving many of their lives. Rosie Hackett and Brigid Davis organised the kitchen, Stephen Murphy organised the men, and together they proceeded to put what would became Saint Ultan’s Children’s Hospital in order. The building work necessary to adapt the premises was carried out by one time “back of the church” resident James O’Neill and his Irish Citizen Army building crew in between the refurbishment of Liberty Hall. Ironically their first patient was Citizen Army man Bill Oman who collapsed with the flu shortly after his wedding. His progress to recovery is chronicled in the pages of Lynn’s diaries.

One of the early recruits to work at Saint Ultan’s was Fly Caffrey from Abercorn Road. Fly had literally been born on the dockside, as his mother gave birth on a ship while being transported to England. Normally, under such circumstances, someone would have simply wrung Fly’s neck. Thankfully, Mick Caffrey took a shine to the infant, he was spared this grisly fate and Mick took him home and reared him. Fly was a lamb, who promptly grew up believing he was a dog and behaving accordingly. To the delight of local children he took them for rides on his back and joined in their childhood games on the street whether invited to or not. Local children would knock on the Caffery’s door to ask if Fly could come out to play and often returned minutes later crying “Mrs Caffrey Fly chased me and knocked me down.” Fly obviously had a winning personality because Lynn also took a shine to him, and he eventually took up residence and employment at St Ultans.It was a wrench to the family and a great loss to a generation of Abercorn Road children but for a number of years the grass of Saint Ultan’s Garden was kept in peak condition by this one time popular North Dock resident. Christine Caffrey had served under Lynn in the Citizens Army and was a veteran of the Stephens Green Garrison in 1916. To the Caffrey’s, presenting Fly repaid a debt long overdue.

Back row, from right to left is Christine Caffrey, Brigid Davis, Maire Ryan and Rosie Hackett (partly obscured).

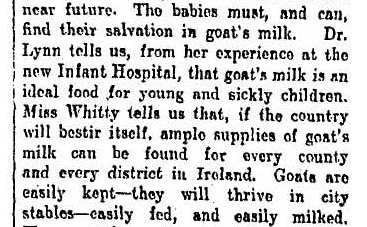

Fly wasn’t the only animal to make an appearance at Saint Ultan’s. The annual reports on the state of public health in Dublin list fines imposed by Sir Charles Cameron on unscrupulous Dairy owners who purveyed what Lynn called “poison” on an unsuspecting public. There had been over 1100 of them in Dublin in 1886 and over the next forty years Cameron’s campaigning saw them reduced to 224 by 1914. Diluting milk with water and increasing the salt content were part of unsanitary production practices. This essential beverage often carried tuberculosis and typhoid contributing greatly to the infant mortality rate in the city. Lynn’s plan to circumvent this was to acquire a small herd of goats for St Ultan’s guaranteeing a constant supply of pure nutritional milk for the infants in their care. Fly Caffrey kept his new companions in check. Following his sad death they regularly wrecked havoc in the hospitals grounds as the gardener struggled to exert control of this most useful but unruly crew.

During the Rising, Michael O’Doherty from Common Street was shot 14 times at Stephens Green. He was a prominent Trade Unionist with the ITGWU and had a degree of vanity about his appearance. In a 1913 photograph of Larkin speaking in O’Connell Street he can be seen with his hat tilted upwards to the left with a similar pose seen in the ICA photo outside Liberty Hall with the “Neither King nor Kaiser Banner” unfurled. O’Doherty was taken to Mercers Hospital and later the military hospital at Dublin Castle. A VAD nurse there was so concerned for the extent of his wounds as she watched the blood seep through the bandages covering his head that she daily prayed that he would die. However he made a full recovery although his face was horribly disfigured, but vain as ever, he simply looked for assistance to comb his hair and proceeded to inspire all the patients both rebels and soldiers undergoing treatment. These included Cathal Brugha in the bed beside him who had been shot over 20 times. O’Doherty lost an eye, an ear, and his face was badly distorted from where his cheekbone had been shattered. While the various doctors “did their bit” to patch him up, it was Kathleen Lynn, aware of O’Doherty’s vanity, who arranged to have a false eye fitted at her own expense. O’Doherty died in 1919 and had a spectacular funeral from Laurence O’Toole’s Church organised by Countess Markievicz. Despite his ailments he had some semblance of normality in his final years due to Lynn’s kindness.

During the battle of O’Connell Street in 1922, Maire Comerford recalled Lynn being everywhere, syringe in hand, treating the wounded. When Cathal Brugha’s luck ran out it was Lynn who tried in vain to save his life. Brugha asked that a mass be said for him which she agreed to. It was later asked of a priest on the missions in China to say the annual mass for many years. In gratitude, generations of Chinese boys were christened Cathal Brugha in memory of the Irish Republican.

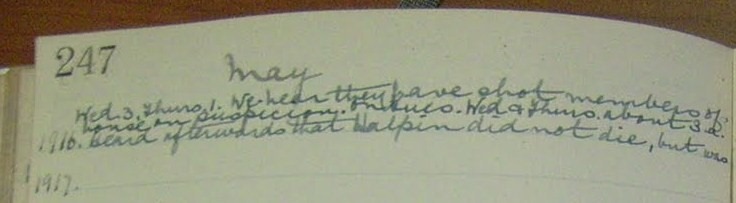

Lynn’s diary, a very under used source for the revolutionary period, begins just before the occupation of City Hall in 1916. It records her capture and imprisonment in Ship Street Barracks where she immediately set out to improve the conditions of her fellow female prisoners. Then over a number of pages she records the progress of Willie Halpin of Hawthorn Terrace including the rumour that he had died in the Castle Hospital on the 27th April. Halpin was Shop Stewart of the United Society of Boilermakers and Shipbuilders at the Dublin Dockyard and Treasurer of the Citizen Army. Willie had hidden in the chimney of the City Hall to evade capture and was close to death when he was discovered. Lynn immediately intervened with the British Army Medical Officer on his behalf which probably saved him.

However, Joe Good, a London born member of the Irish Volunteers, also gives credit to a British soldier for his contribution to Willie’s return from the grave in an amusing anecdote. Willie, although a private in the ICA, had a fondness for wearing a sword and elaborates braid on his uniform. Cruelly his ICA comrades christened him “Napoleon Halpin.“ For Easter week he had invested in so much gold braid that Good described him “as like a chocolate soldier.” Halpin didn’t drink alcohol but a kindly British soldier poured some whiskey into his mouth to revive him, which, according to Good was “the first drop in his abstemious life” and “all but killed him.” The soldiers then carried Willie, “half choking on whiskey, with his scabbard dangling” into a room where several of the condemned leaders of the Rebellion were being held. Then dropping him on the floor, an officious sergeant announced to the assembled leaders “here’s your brigadier general!”