“If loving my country through my whole life should make me wretched, I am wretched indeed…I am ready, my lords, for my sentence”

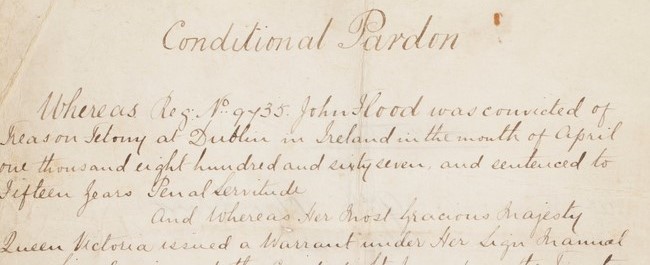

These were the words spoken by Dublin man John Flood on the 21st May 1867 as he was found guilty of ‘treason felony’ and sentenced to 15 years transportation to Australia. Described as the overall leader of the Fenian movement in Great Britain and Scotland, he had been arrested after a near escape and boat chase on the River Liffey. Never to return to his native soil, he would live a long and prosperous life in Australia, and two years after his death in 1909 up to 3,000 people attended the unveiling of a monument at his grave in Queensland. A one time resident of East Wall, this is his story…

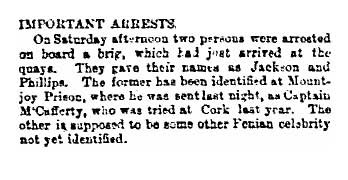

On the 23rd February 1867 the Collier Brig (a coal boat) New Draper sailed up the Liffey into Dublin Port. Its approach did not go unnoticed, as police and troops awaiting its arrival were stationed on the Quay-side North and South. As it made its way along the river, two men dropped overboard into an awaiting Oyster boat and were rowed away. This sparked a pursuit which also involved a ferry and a canal boat before both men scrambled abroad another Collier where they were eventually arrested. They gave their names as William Jackson and John Phillips. They were in fact two Fenian leaders- ‘Jackson’ was the American John McCafferty and ‘Phillips’ was John Flood.

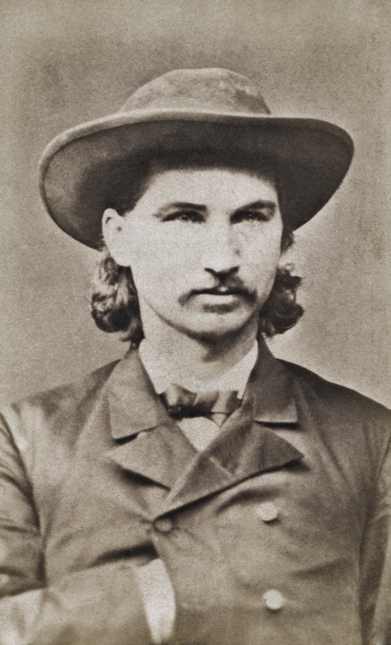

“The clever and dashing young attorney…

… the still more clever and dashing young smuggler”

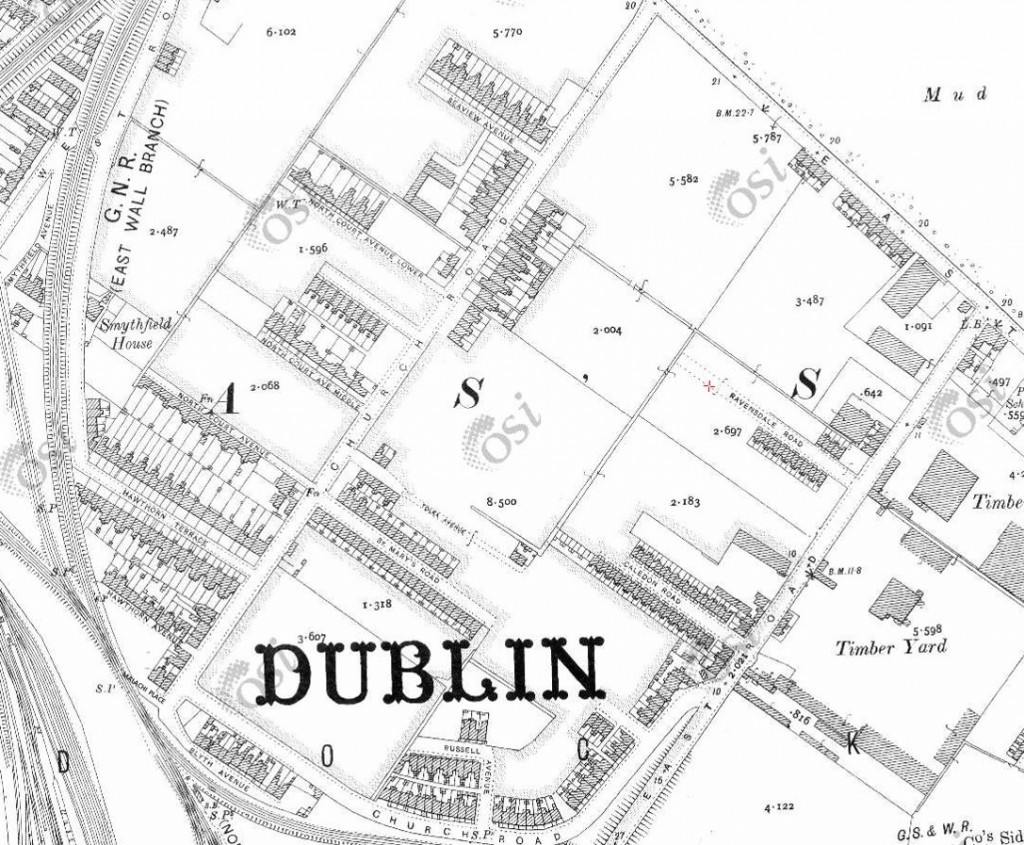

John Flood was born at Sutton in Dublin on the 2nd of May in 1841. His father was the owner of a shipping company .He was educated at Clongowes Wood, County Kildare. Fresh from College he studied for some time under the eminent barrister, Isaac Butt .Details of any other residences during these years are unclear but we do know that by the time he was in his early 20’s he was living at Malachi-Place off Church Road , East Wall. He was employed as a as a clerk or apprentice at a solicitors firm based at number 34 Lower Gardiner Street.

At this time he also had other business interests, on the opposite side of the law:

“Unfortunately for himself, like many young men of an adventurous spirit, he formed a taste for a roving life. He embarked in smuggling transactions…upon one memorable occasion he acquired no little notoriety as a defendant in a prosecution which was instituted against him for breach of the revenue laws”.

Issac Butt would later make reference to him as “Mr Flood the clever and dashing young attorney … Mr Flood the still more clever and dashing young smuggler” and stated that he was “beyond all question engaged in smuggling enterprises- boldly, successfully, and extensively engaged in them”.

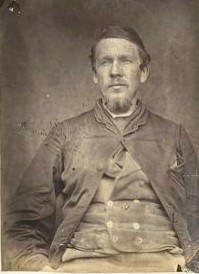

A number of descriptions of Flood emphasise that he was of striking and distinctive appearance: “A fine looking man, of large person, and frank, handsome features, adorned by an ample beard of a tawny colour, his bearing was upright and stalwart” .His twin careers on either side of the law were not his only passion, as “the troublous condition of his native land at this time enlisted his sympathy and he entered with patriotic fervor into the Fenian movement of the ’60s, quickly becoming one of the trusted leaders in the organization”.

“strong manly forms, eyes with hope gleaming”

“John Flood when quite a young man, with a career before him, heard his country call, and he responded to that call in no uncertain note. He gave up a career that would have undoubtedly led him to a pre-eminent position in the legal profession, and took his stand with the rank and file in that great movement known as the Fenian Movement of ’67. Along with Colonel McCafferty and such men as James Stevens, he set himself to get the Irish people to band themselves together and to tolerate the system of tyranny and oppression no longer”

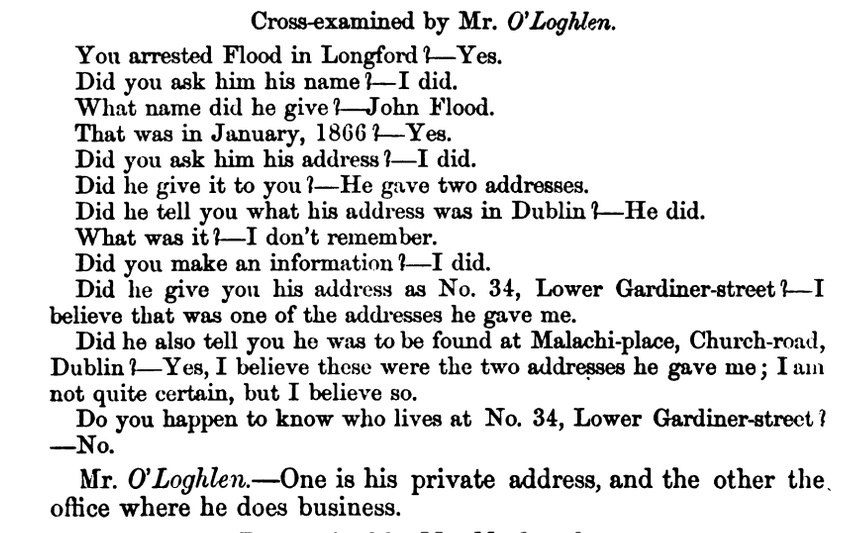

The first ‘official’ suspicions against Flood as a Fenian were probably in January of 1866 when he was arrested in the Longford in the company of known Fenians. Upon being searched a receipt for ammunition (that would ‘fit a French rifle’) was found upon him. Lacking any other evidence he was released without charge. He had given his correct name and two addresses, his home and his place of employment but when asked about his profession was he replied ‘a gentleman at large’.

The Fenian movement was born out of the failed Young Ireland rebellion of 1848. Amongst the participants who fled the country afterwards were James Stephens and John O’ Mahony. After spending time in Paris together Stephens eventually returned to Ireland and from Lombard Street founded the Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B) while O’Mahony travelled to New York and founded The Fenian Brotherhood. Eventually both organisations would unify, with their goal “to make Ireland an Independent Democratic Republic.” The word Fenian would come into common use as a generic term for Irish Revolutionaries. A newspaper The Irish People was founded and operated from Parliament Street, almost in the shadow of Dublin Castle. There was an informer in the office of the paper and in 1865 a developing plan for an insurrection led to it being raided and all those associated with it arrested.

(The informer was Pierce Nagle, a paper folder in the office. He lived for some time ‘in lodgings off Sheriff Street” and was “so remarkably respectable, and in every way so upright and virtuous, that he was selected by the Catholic clergymen of St. Laurence O Tooles Church to fill the office of clerk”. He afterwards fled to England in fear for his life, with good reason it seems as “Some time afterwards his mutilated body was found under the arch way of one of the London bridges, a large bacon-knife, on the handle of which was the inscription, “Death to traitors,” being embedded in his heart.”)

Those arrested included Stephens, but after a short stay in Richmond Barracks his escape was facilitated by Fenian prison guards. John Flood “became specially distinguished by his participation in the arrangements for the escape of Stephens from Ireland. He accompanied Stephens and Colonel Kelly in their perilous journey from Dublin to Scotland. Adverse winds blew their boat into Belfast Harbour with the loss of their tiller; and it was owing to Flood’s knowledge and experience that the party were saved. He received a severe injury in the hand letting go the anchor in the hurry to prevent their being driven too far into the harbour. Flood saw Stephens safe to Paris and after a few days returned to Ireland, and almost immediately took his position as one of the first officers of the English and Scotch organisation”.

(His Australian convict record notes a distinguishing mark as a “Small cut on lower joint of left fore-finger”, a souvenir of the Stephens escape)

“If it had not been for the inevitable traitor…”

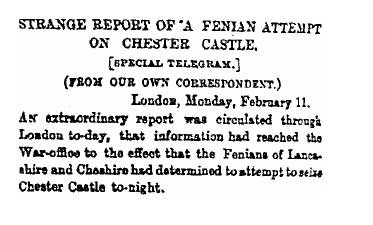

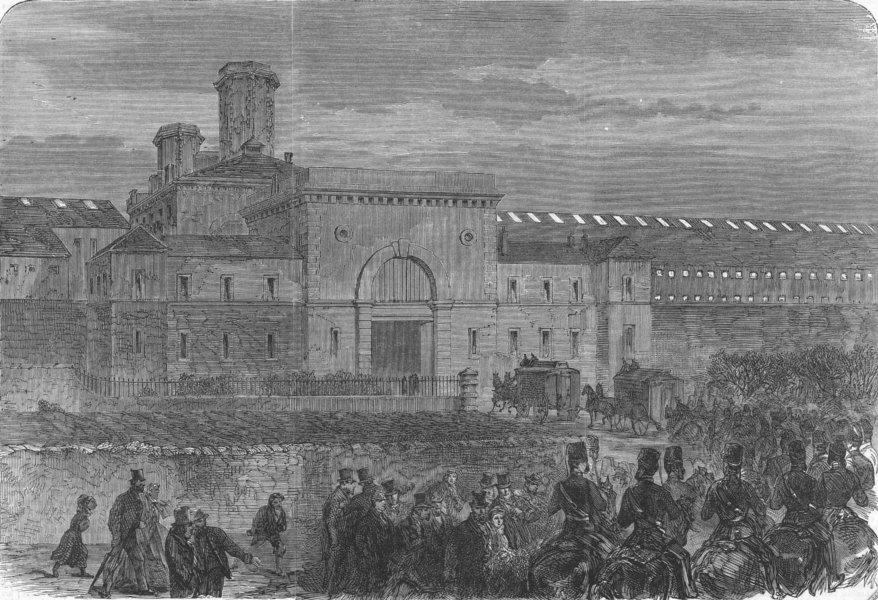

Once again a Fenian rising in Ireland was being been planned, initially for February of 1867 but it was agreed that this should be delayed until March. To help equip the insurrectionists, an attempt was to be made to seize the armoury at Chester Castle. The plan was probably initiated by information from IRB men within the British Army. The intention was that a large body of men would ’infiltrate’ Chester and seize a cache of rifles belonging to the local volunteer corps. These would then be used to storm the Castle which had a standing garrison of just 60 regular soldiers. It arsenal contained 10,000 rifles and 900,000 rounds of ammunition, which would have been an incredible haul for the Fenians. Once successful, the next step would have been to commandeer a train, take the arms to Holyhead, seize a steamer, sail to Wexford and look forward to a successful and well-armed rebellion. The leader of this audacious operation was the U.S. born John McCafferty, a veteran of the Confederate army during the Civil War, who was closely assisted by John Flood. Monday the 11th of February was the scheduled date for the plan to be enacted.

Things did not go as expected, as the notorious informer John Joseph Corydon (who had infiltrated the Fenian leadership) passed on the plans to the authorities the previous day. The rifles of the Chester Volunteers (needed to initiate the main raid) were moved into the Castle, and an additional body of 70 troops from Manchester strengthened the Garrison.

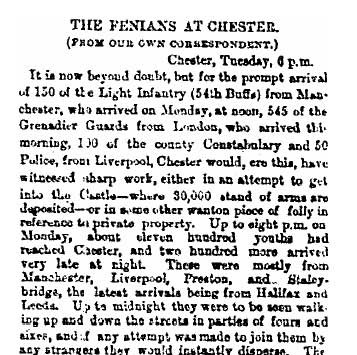

McCafferty and Flood went out for dinner on the Sunday afternoon and realised from the activity they witnessed that their intentions were known. They managed to very quickly disappear, but not before sending a messenger with a countermanding order to other Fenian officers. Despite these efforts to turn their men back, an estimated 1,300 Fenians reached Chester, in small parties from Manchester, Preston, Halifax, Leeds and elsewhere. According to a contemporary report:

“Hundreds of strangers poured into it with an ominous air of mystery, and dispersed silently through its quaint streets. The magistrates, the volunteers, the soldiers and all the guardians of the peace that could be enrolled, were preparing, as in old times, to watch all night, and were on the alert for a sudden attack.”

However, with the raid abandoned, the Fenians discarded the few weapons they had (a small number of revolvers were recovered from a Canal) and melted away. The Times reported that ‘about 2000 Irish roughs passed through the New Ferry Tollbar on their way from Chester to Birkenhead. They came in gangs of 30 or 40, and seemed to be much jaded and dispirited’. The following day a further 500 household troops arrived by train from London. (As there was no longer any threat, it is said that they arrived ‘in time for a tumultuous reception and breakfast at Chester hotels’).

While this was an anti-climactic conclusion to such an ambitious conspiracy, the contemporary press did recognise it’s significance and potential:

“..the mere look of some of the strangers was sufficient to indicate their character, if not their purpose. We must certainly give the Fenians credit for having formed a bold plan, and for having put it into execution with considerable promptitude. If it had not been for the inevitable traitor there is too much reason to fear they would have had at least a partial success”.

The Attorney General was much more direct in his assessment: “If that project had been carried out, it would be impossible to exaggerate the disastrous consequences to this country which might have followed”.

(When the planned rising in Ireland finally took place the following month it was a disaster – the lack of arms was a major factor in it’s failure , but the ever present informers in the ranks , most notably Corydon, had a major impact too. Neither John McCafferty nor John Flood would play a direct role in these events, as by this time they were already behind bars).

After the aborted raid at Chester the identity of McCafferty and Flood was well known, not least because of the actions of ‘Corydon’ .They would have been amongst the most wanted men in Britain and they knew the risks of either staying there or attempting to return to Ireland. But the uprising was drawing near…

A police detective on duty at the rail station claims that while McCafferty and Flood may have initially left Chester and headed to Manchester they returned, and were seen on Monday “in communication with large bodies of working people who were arriving by train”. That evening they left on the Birkenhead train. They avoided the usual passenger routes back to Ireland, but 9 days later they set sail on their return journey.

‘two persons of suspicious appearance’

“The New Draper arrived in the river here on the 23rd February, towing up an oyster boat. She came near her berth at the Custom House, but before she reached it these two men, Flood and McCafferty, dropped from the stern of the vessel into the oyster boat, and were rowed towards Carlisle-bridge. They were pursued by the police, who had been informed they were coming over by this vessel, and were on the look out for her; indeed, one of them had followed her all the way from Pigeon House. They were called on to surrender, which they did not do, but sought to escape by jumping into a canal boat, and from the canal boat into a collier. They were there arrested, and gave false names.”

Charles Smith, Captain of the New Draper out of Whitehaven, normally engaged in the Coal trade,had agreed to give the two men passage to Dublin, leaving on 20th February. They reached their destination three days later, and in the Bay a tug steamer took the vessel in tow and proceeded up the river. Throughout this time they were under constant observation, as the authorities had been made aware that ‘two persons of suspicious appearance’ had sailed aboard. Near the pigeon-house a small boat (described as a row boat, but with a small mast) approached and a rope was thrown down to pull it alongside. The New Draper was due to berth at Georges Quay on the South side of the River opposite Custom House. As it was preparing to dock the two passengers made their exit onto the small boat and were rowed away. As they left, one of them politely addressed the captain with the words “Goodbye, I’ll see you again”.

Thomas Reilly, a police Sergeant based at College Street was one of those awaiting their arrival, positioned on Sir John Rogersons-quay. As they made their way up the Liffey he could observe those on deck and ordered his men to proceed along-side, moving as far as Creighton Street / City Quay. Here he climbed aboard a Collier to gain a better view and witnessed the wanted men make their way into the small boat and be rowed away by two men, towards the other side of the river. He rushed along onshore and accompanied by another constable commandeered one of the Liffey Ferry boats and gave pursuit into the centre of the river. They shouted a command to surrender but were ignored. Flood and McCafferty leaped from their boat into a canal-boat and from here scrambled aboard another coal-brig.

Police constable Michael Rowland was located at the Point of the wall (on the North Side of the River) when the New Draper was towed past. He crossed over on a ferry-boat and on the way he witnessed the two men climb into the smaller boat. Having reached the South Quay he joined Sergeant Reilly in the pursuit aboard the commandeered Ferry boat, and afterwards onto the canal-boat and finally onto the coal-brig.

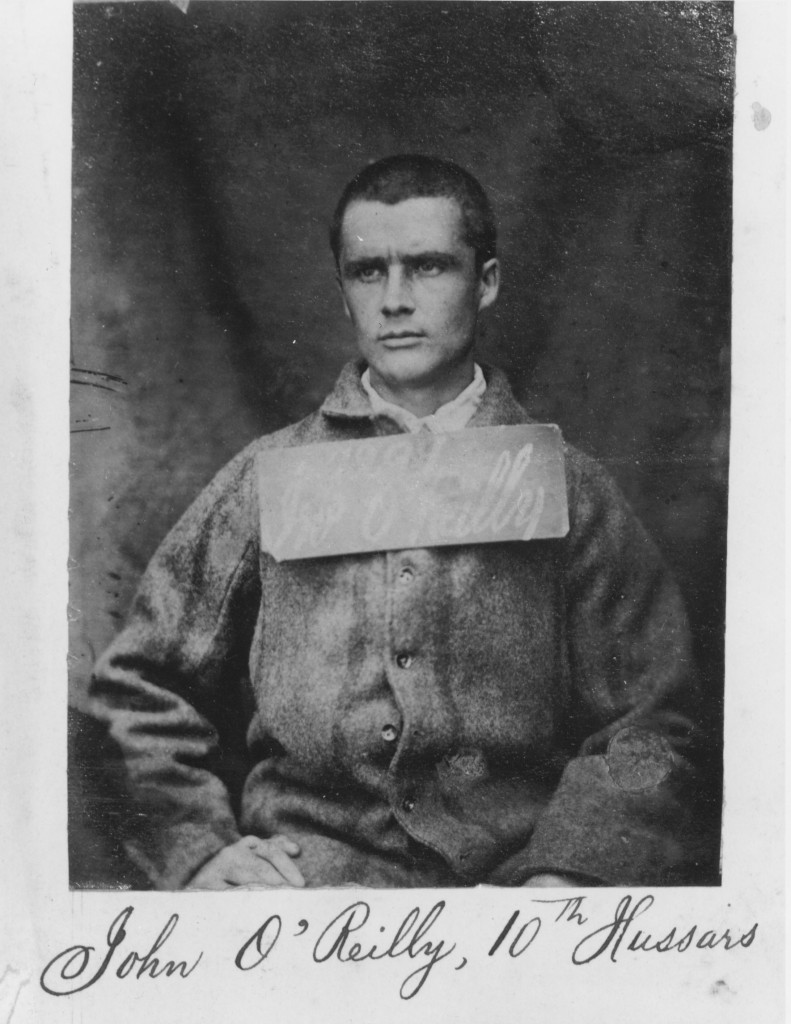

It was here that O’Reilly and Rowland arrested the two men. Identifying themselves as William Jackson and John Phillips, they were initially returned to the New Draper before being taken to Mountjoy Prison later that evening.

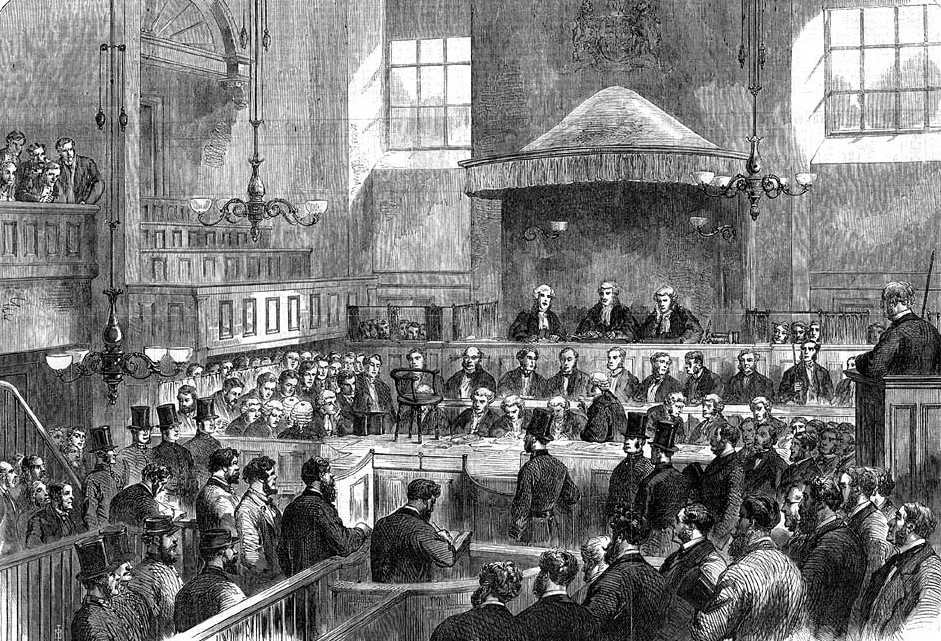

“…never was our country so humiliated in an Irish Court of Justice”

The Special Commission held at Green Street Courthouse began on April 8th, with 265 men accused of High Treason and Felony Treason. McCafferty was tried separately and on his own. On the 15th of May Flood faced trial alongside Edward Duffy and James Cody. Amidst the general treason / conspiracy accusations, Edward Duffy was specifically named for ‘seducing men away from the army’, and Cody with being head of ‘an assassination committee’ which was tasked with killing ‘any man who should be found giving information to the authorities of the movement of Fenians’.

The informer John Joseph Corydon gave evidence against all three and many of the others on trial. His testimony was the most substantial and damning against Flood. Civilian witnesses confirmed that Flood had been in Manchester very regularly during the previous year but made no claims to any criminal or conspiratorial activity on his behalf. Likewise he was identified as present at various locations in and around the time of the Chester raid. This was all corroborative to Corydons accusations. Aside from the informer, the most detailed evidance regarding Flood and Fenian links came from a Dublin Detective.

Launcelot Dawson, Police Constable,gave evidence of his special duties in 1864 and ’65 when he had been engaged in watching Fenian meetings and Drill assemblies. He described his time observing one particular large store-room (near Island Street) where drilling took place. He described those who attended as ‘of the labouring classes generally’, and entrance was gained by knocking or giving a ‘peculiar whistle’, with the two men posted as ‘sentinels’ granting admission.

“These persons generally went there about seven o’clock, or between seven and eight; and continued to go in there in batches of twos and threes up to nine o’clock, or half past nine”. He stated that “fifty or sixty, and sometimes up to eighty…” used to assemble on these occasions.

He “procured a key , and got access to the premises after they had all left” . It was ‘a very extensive place’ which he believed to be a former wool-store .Paraffin lambs hung around the walls ‘secured by nails’ and the windows were “boarded up , so that no one could see what was going on inside from the outside” . It also contained ‘some basket hilted sticks such are as used for the broad sword exercise” and no seating at all.

He claimed that he had first noted John Flood in December of 1864 at Burkes Public House on Dame Street and afterwards observed him entering the store on at least three separate occasions when drilling was taking place. Each time he only stayed ‘perhaps an hour, or sometimes not even half an hour’.

He did not know Flood at this time, but said he had seen him ‘about town’. When cross-examined ‘Do you know everyone about town?’ he explained “No; but he is about the class of man who would attract my attention”. He added that he had “Met him in several parts of the city …the principal place I met him was down about the North Strand”. At the drill hall, he had taken down a description of Flood, the clothes he wore and ‘the colour of his whiskers’ but did not know his name, and afterwards did not see him until he was in custody at Mountjoy.

As stated, the most substantial evidence against Flood was from the informer John Joseph Corydon. His background and role was fully detailed in court – he was a former lieutenant of the Federal Army of the United States who had joined the Fenians in 1862. He came to Dublin in 1865 and knew the key figures such as James Stephens and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. He lived first at Summerhill and then at Buckingham Street. In 1866 he began passing information to the authorities. That year he moved to Liverpool, and was based here during the planning of the insurrection and the Chester Raid. He was the most significant and high ranking informer in the ranks, betrayed the rising and gave evidence against many of the leaders in subsequent prosecutions.

He first met Flood in 1865 , and described him as “the principal leader, or head- centre in England and Scotland in the absence of Stephens”, and that “Liverpool was his headquarters”. He attended meetings with Flood, McCafferty and American Fenian officers including the planning for the Chester raid.

He described a meeting in Edgeware street in Liverpool prior to the events in Chester at which Flood and McCafferty gave the orders regarding the proposed raid, capture of weapons and transportation to Ireland and provided finances (£20) to enable members to make their way there. He also detailed meetings with American Fenians (who were to be officers on the raid) and his own traitorous activities to prevent the plan being enacted. Issac Butt, a one time legal mentor to Flood would now take charge of his defence against the serious accusations he now faced.

It was questioned whether such a conspiracy ever actually existed, or if it was just an invention of the informer Croydon to improve his own value:

“How easy to pervert some intended prize fight, some gathering of a trades union into an alleged treasonable attack, and elevate himself…”

“…not one single human being has been prosecuted in England for participation in that treasonable design. In the centre of one of Englands most peaceful and prosperous districts of peaceful and loyal England, hundreds of persons assembled in that quaint old city of Chester to raise the standard of open rebellion, to make war upon the Queens troops , to seize upon one of the strongholds of the nation in open day. They came in troops from every quarter; they filled the streets of the town; and disappear as mysteriously as they came. And of all the crowd that met there in the broad sunlight- if you are to believe the story- in an act of open and audacious rebellion, not one has been prosecuted or brought to account… a rebellion passed off as a matter of course- and at this hour no single individual has been made amenable to justice for being in Chester with that party of traitors on that day”.

The fact that the trial was taking place in Dublin was highlighted and the question asked (and answered): “why was not Flood tried in Chester where the treason was committed? There is but one reason which can be assigned. They dare not submit to an English jury the evidence on which they ask you to convict”.

The character of the informer Croydon was of course brought into question, and no hyperbole was spared: “Ireland has been subject to many insults; she has borne many humiliations. But never was our country so humiliated in an Irish Court of Justice, as when this degraded ruffian was spoken of by the Queens Attorney-General as ‘Mr. Croydon, the saviour of his country’…

The evidence that Flood had been in Chester was irrefutable, with many witnesses to his presence there. The tactic of the defence was to throw doubt on his reasons for being there, even invoking his reputation as a ‘Clever and dashing young smuggler’ to full advantage – “Where is the direct and manifest proof that his presence in Chester was connected with any treasonable purpose whatever? Can you say that he is provably attained by any overt act or deed? If you cannot you must acquit him. He may have been at Chester for a thousand purposes of which you and I know nothing. He may have left it clandestinely for a thousand reasons we cannot divine. He may have been engaged in some smuggling transaction. He may have been assisting McCafferty to get away. Everything is conjecture, and upon conjecture you cannot bring in a verdict of guilty…”

John Flood was found guilty of Treason Felony as were his co-defendants. On Tuesday 21st May he gave his speech from the dock, which defiantly stated:

“The Attorney-General has alluded to me repeatedly as that wretched man. If loving my country through my whole life should make me wretched, I am wretched indeed; for I tell you now, and I tell the world that I not only abhor assassination, but I would rather go to my doom than be guilty of the moral assassination that has been practiced against me. I am ready, my lords, for my sentence”.

He was sentenced to fifteen years penal servitude. His expectations were probably worse. Tried separately, John McCafferty had already been convicted of High Treason and sentenced to death, though this was afterwards commuted to ‘penal servitude for life’.

After the sentence had been pronounced the convicts, who had been held in cells beneath the court, were conveyed to Mountjoy Prison, escorted by mounted police and two troops of Ninth Lancers. Five months later Flood had been brought to Britain and facing transportation to the far side of the world, a journey of almost 10,000 miles.

To Australia with ‘The Wild Goose’

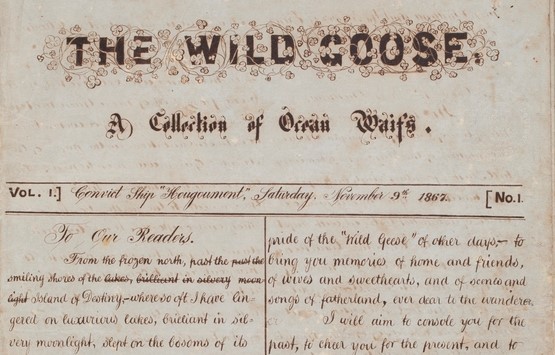

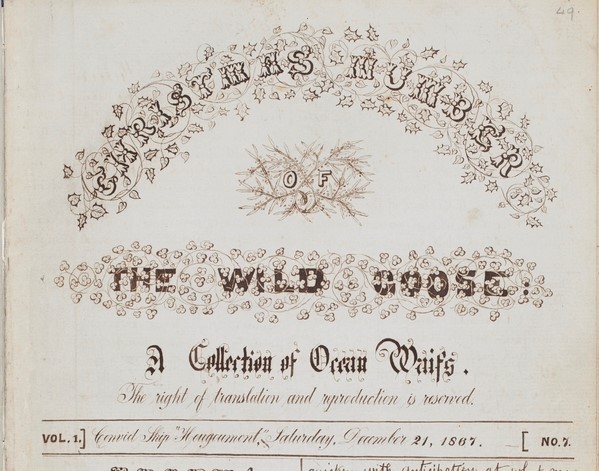

In October of that year Flood was aboard the ship Hougoumont which set sail from Portland in the South of England, bound for Freemantle, Western Australia. A three month journey, this was the first such transportation in almost 20 years (since the Young Ireland rebellion) and it would be the last such voyage of a prison ship. Aboard were 280 convicts, and amongst these were 62 Fenians. A plan was proposed by some of the Fenian prisoners for the seizing of the ship and sailing her to America,with John Flood as the navigator. A lack of support and concerns about how the two hundred plus criminal convicts would react led to the plot being discarded. As a result the voyage was generally uneventful, but remarkable in that for much of its passage the Fenian prisoners produced their own weekly paper.

In a letter sent to his parents from Australia, Cork man Eugene Lambert detailed the journey:

“We enjoyed a tolerable passage and arrived here on the 9th January, making the voyage in 89 days. Really I was heartily sick of life on board ship, the journey was so long. I managed one way or other to while away the time. Myself and my exiled friends lived very agreeably during the passage. We were kept separate from other prisoners and placed in a good part of the ship nearly amidships. We published a written newspaper on board, entitled “The Wild Goose”. I was a copyist on it and it was edited by J.Flood, he that was tried with Capt. McCafferty….Only half the voyage was over when ‘twas thought of. It was our greatest delight to have a read of it…”

Denis B. Cashman, a Waterford Fenian kept a diary which was later published. His entry for November 5th 1867 records

“a meeting held to see if we could start a newspaper. Meeting composed of Con Mahony, J.Flood, Duggan , O’Reilly, Cody, Casey, Noonan and self…J. Flood appointed editor…”

As Irish patriots bound for foreign shores, the appropriate title “The Wild Goose” was chosen. The Chaplin aboard the Hougoumont was Father Bernard Delaney of Dublin, who was friendly towards the Irish prisoners. He provided the necessary paper and ink for the task.

A vivid reminiscence of preparing the paper was provided by John Boyle O’Reilly: “We published seven weekly numbers of it. Amid the dim glare of the lamp, the men at night would group strangely on extemporised seats. The yellow light fell down on the dark forms, throwing a ghastly glare on the pale faces of the men…”

A total of seven weekly issues of “The Wild Goose” were produced, which included a double sized Christmas edition of 16 pages. Saturday was publication day and the Fenians would look forward to gathering in one of the ship’s holds and having the paper read aloud by the editor John Flood or his assistant, John Boyle O’Reilly .The content was not overtly political, but was designed to be diverting and morale building. It featured stories and poems, history pieces, memoirs of home and a fair bit of humour. It set out its ambition on the front of the first edition “I will aim to console you for the past, to cheer you for the present, and to strengthen you for the future”.

One contribution rejoiced in the memory of a spectacular Fourth of July celebration spent in Chicago. It concluded with a patriotic ambition -

“Thus do the Americans commemorate their country’s natal day. That night, sadly contrasting the position of my own country with that of the proud American republic, I fervently prayed that a happier day might dawn for my own native isle of the sea.”

John Flood contributed poetry under the name Binn Éider (The Gaelic name for Howth is Binn Éadair ). A total of eleven of his poems appeared across the seven issues, all described by later commentators as of good quality.

“Amid scenes that lie, oh! so far away

From my prison home to-night –

By the lovely shores of sweet Dublin Bay

And Ben Eder’s crowned height,

Behind whose hills oft I have seen thee rise …”

(“My Star” 10/12/1867)

One in particular “Cremona” recalled the battle in the 1700’s when an Irish Brigade fought alongside the French against the Austrians. It is not hard to imagine the emotion Flood might have felt when he penned the lines

“A curse upon the traitor wretch who to the wily foe

For sordid gold the town betrayed! “

Amongst the bumper crop of material appearing in the final edition , the double sized Christmas special, were two contrasting poems by John B O’Reilly .“Christmas Night” described the circumstances of an Irish prisoner in an English gaol on the feast day , quite clearly based on his own incarceration in London the previous year.

“And thus he spoke as he onward sped-‘truly every heart is light;

In merry England from east to the west, no mortal is sad tonight!’

But now in his path stood a gloomy pile, ere the cheering thought had passed:

A prison, all massive, and silent, and stern, its darkening shadow cast.

The air grew cold and his boisterous mirth was struck with a sudden chill;

For tho’ keen are the frozen blasts of the North, there are others more piercing still.”

But the paper was designed to be uplifting and morale building , and another Christmas verse was more light hearted and cheery –

“Then, brothers, though we spend the day

Within a prison ship,

Let every heart with hope be gay, a smile on every lip.

Let’s banish sorrows, banish fears,

And fill our hearts with glee,

And ne’er forget in after years

Our Christmas on the sea”.

The Hougoumont reached its destination on the 9th of January 1868, the last vessel to carry convicts and political prisoners to those shores. When John Flood set foot on Australian soil he was in the land that would become his home for the next four decades, until his death in 1909.

(Incredibly, copies of the ship-board newspaper have survived. A century after the convict ship Hougoumont arrived in Fremantle the original hand written manuscripts of The Wild Goose were donated to the Mitchell Library in Sydney by Sheelagh Johnson the great granddaughter of John Flood.)

“He was a friend of whom anyone might be proud”

He had been sentenced to 15 years penal servitude, but after only a few years of his sentence he was released, on the condition that he would not leave Australia or attempt to return to England or Ireland. Now a free man (at least on one continent) he set out to make a new life for himself.

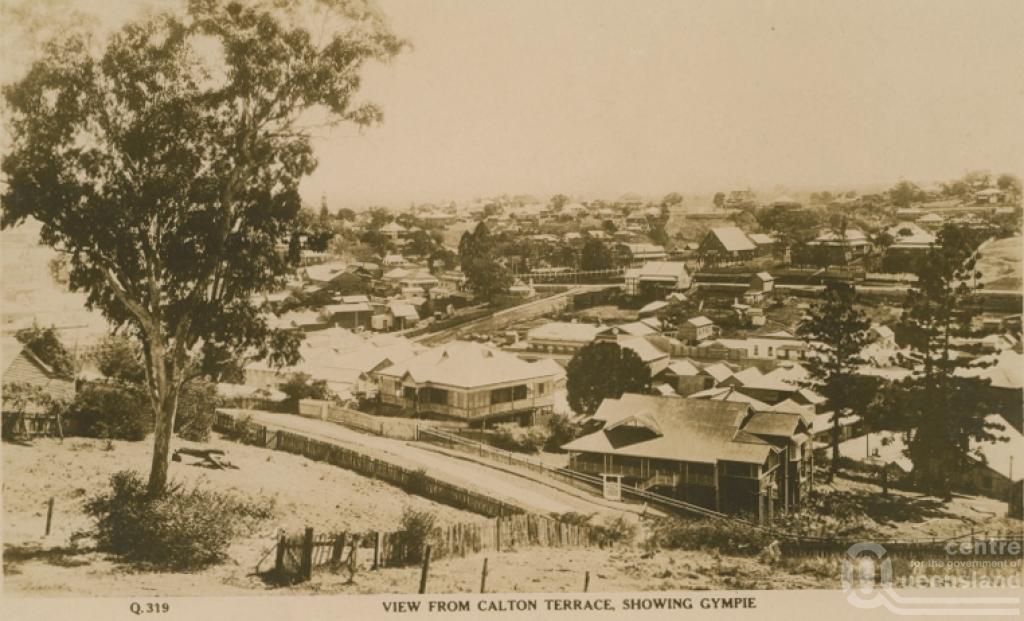

Perhaps inspired by his journalistic endeavours on the ocean, he would become a ‘Newspaper-man’, and also become involved in the thriving goldfield and mining industries. Having proceeded first to Tasmania, he then went on to Sydney, where he established his own paper called “The Irish Citizen” in December of 1871. This bore the imprint “Printed and published by the proprietor, John Flood, at No. 6 Park-street, Sydney.” and would run until August of the following year. In 1873 there was a gold-rush on the Palmer River in the Northwest, which attracted him, but he still had ink in his veins, as he soon became editor of a paper in nearby Cooktown, (Queensland). He would also spend some time on the ‘literary staff ‘of the “Brisbane Courier”. In 1881 he arrived in Gympie, another Gold-rush town in Queensland, setting up “John Flood and Co.” establishing himself as a mining secretary. But the ink beckoned again, and in 1888 he set up the Gympie Newspaper Company Ltd. and acquired the “Gympie Miner” daily. He maintained his role in the company as a managing –director and also in its ‘journalistic control’ until the early 20th century.

In Cooktown he had married a Tasmanian woman, Miss Susan O’Bryne, and they had a number of children. Three of these would die at young ages over a reasonably short time span – Valentine Patrick in 1889 (aged 6), Kathleen in 1890(aged 9) and John Oscar in 1892(aged3) His wife died in 1897 at the age of 44, and at the time of his own death in 1909 only two of his children were still alive.

A monument “placing on record the life of John Flood”

During his years in Gympie he was a prominent citizen, who “always took an active part in local affairs”. In relation to his native land, he was “especially recognized as a leader in all movements having reference to the Irish National question. On these matters he was consulted by those connected with the Irish Home Rule movement in all parts of Australia, and maintained a continuous correspondence with his native land. When Messrs. Redmond, Dillon, Davitt, and other members of the Irish National Party visited Gympie they were his guests”.

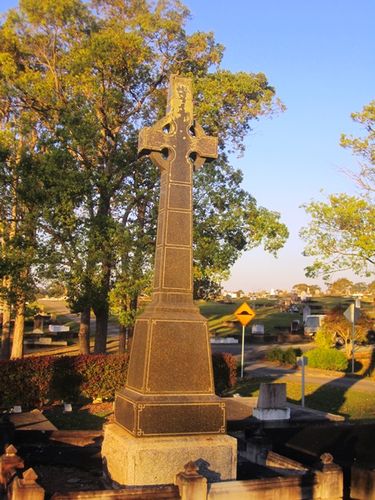

His status amongst the Irish population of Australia was confirmed two years after his death with the erection of a monument to his memory on the 24th September in 1911. These extracts are taken from an extensive account published in the Gympie Times newspaper –

“The hour fixed for the ceremony was 3 p.m., and by that time an assemblage estimated at between 2000 and 3000 persons had gathered round the memorial erected over the grave. The monument which stands 14ft. high is a handsome Celtic cross in polished Aberdeen granite on a Bohn base of unpolished local granite. It is set on a solid base of concrete and the walling and enclosure are Helidon freestone. On the face of the monument are engraved the round tower, wolf dog and national harp of Ireland, with other emblematic designs… A lorry was drawn up on the right hand side of the memorial, on which was placed the handsome banner of the H.A.C.B. Society and with this as an appropriate background the various speakers addressed the large audience from the lorry…”

The chairman of the memorial committee began “today they were unveiling a monument to the memory of one of the most earnest, enthusiastic and patriotic Irishmen that ever lived. (Hear, hear). The late Mr. Flood, as they knew, was prepared to lay down his life for his country, and up to the moment of his death he had never lost his enthusiasm for the cause of Ireland. For his enthusiastic support, he had suffered the penalty of banishment from his native land. Of all the friends, of the late Mr. Flood, he (Mr. Power) living alongside him had a better opportunity of judging his character and know something of his inner life, and, apart from his patriotism and love of country, no better father ever lived. He was a friend of whom anyone might be proud – courteous, cultured, and straightforward, never saying one thing when he thought another”.

Amongst the guests was William Archer Redmond MP, son of John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. “MR. REDMOND who was heartily received, said that cold indeed would be the heart of any Irishman if it was not moved and inspired by the spectacle in the cemetery that afternoon, a crowd assembled in thousands to do honour to the memory of a great Irish patriot and an esteemed fellow townsman... In this truly Irish monument erected by the people of Gympie, they expressed their deep appreciation of and lasting admiration for the sterling qualities of their late townsman, John Flood, and for his self-sacrifice and his unswerving devotion to the cause of his native land and its people.”

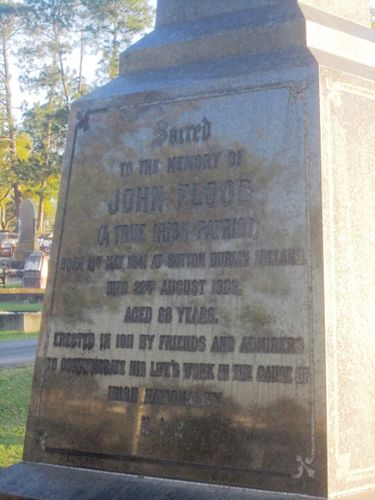

The inscription on the memorial stone reads:

“Sacred to the memory of John Flood (a true Irish patriot) born 2nd May 1841 at Sutton Dublin Ireland. Died 22nd August 1909 aged 68 years. Erected in 1911 by friends and admirers to commemorate his life’s work in the cause of the Irish Nationality. RIP”.

Any corrections, clarifications or additional information please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Sources include:

“The Fenian conspiracy :Report of the trials of Thomas F. Burke and others, for high treason, and treason-felony, &c., at the Special commision, Dublin, held at the Court-house, Green-street, Dublin, commencing 8th April, 1867.” By William G. Chamney. (Printed by A. Thoms, Dublin 1869)

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

State Library of Queensland

www.gympietimes.com.au

www.convictrecords.com.au

www.monumentaustralia.org.au

Fenian Diary.Denis B. Cashman on Board Hougoumont 1867-1868

(Edited and introduced by Dr C.W. Sullivan III)

Voyage of the Hougoumont and Life at Fremantle: The Story of an Irish Rebel

By Thomas McCarthy Fennell

Irish Political Prisoners, 1848-1922: Theatres of War

By Seán McConville

(Dedicated to Belinda , a finder of lost things and a great contributor to the work of the East Wall History Group. )