“…be buried in the usual place in the usual way.”

The site of Ballybough Suicide Plot currently under renovation.

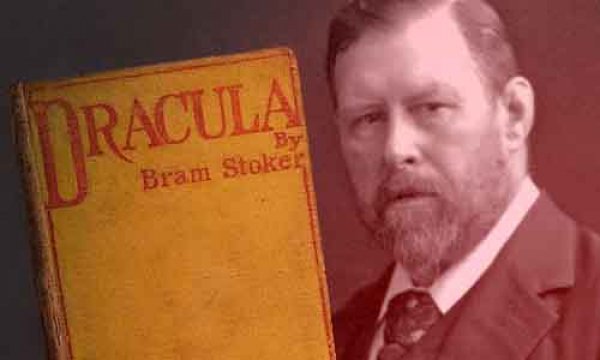

Recent weeks have seen things stirring at the intersection of Clonliffe Road and Ballybough Roads. What was once a derelict piece of waste ground at the site of two advertising posters has now been tastefully landscaped with a pair of benches for weary travelers. The site will be completed in the coming weeks. However, this wasn’t just any old piece of waste-ground, but the location of the infamous Suicide Plot. Often confused with the nearby Jewish Graveyard on Fairview Strand, this historic site is generally believed to have influenced local writer Bam Stoker’s novel Dracula.

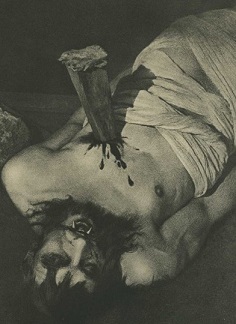

In the 13th century, the English jurist, Henry DeBracton, recorded the ancient common law of Felo de Se (literally Felony against one’s self), which set forth the penalties for those who committed suicide. Under that law, all of a person’s moveable property was forfeited to the Crown and their body was removed to waste lands – unconsecrated ground, near a crossroads, and buried with a stake through the heart. It’s unclear when the law was first implemented in Ireland but dozens of such locations, usually with Cillin or Killeen in their place-name, existed and are slowly being rediscovered by archaeologists today.

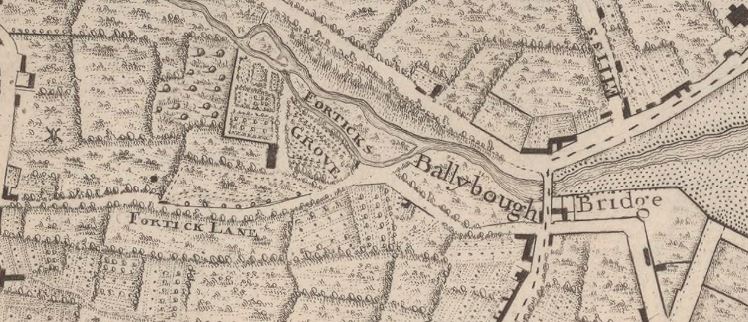

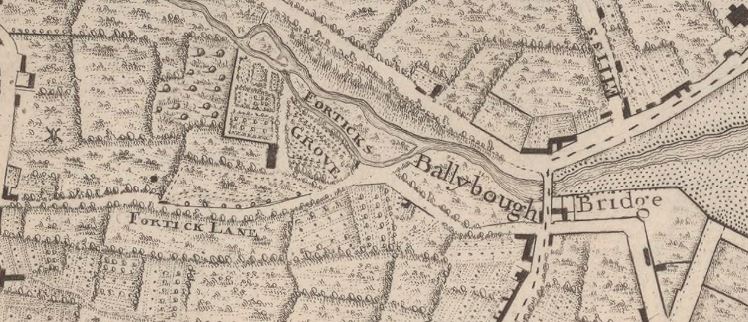

John Rocque’s map of Dublin.

In Dublin there were two sites, The Long Meadow at Islandbridge and the Crossroads at Ballybough Bridge , now the intersection with Clonliffe Road. This was originally known as Fortick’s Lane after Tristram Fortick owner of the Red House which is now part of Clonliffe College. At Long Meadow burials were directed to take place at high tide but it’s unclear if there was a specific time for burials at Ballybough. None of these sites were ever identified on maps. The 1848 Griffith’s Valuation for example, designated the Ballybough Site as part of land owned by the representatives of the Earl of Blessington. However, their common usage was known. Surviving Felo de Se verdicts from the Nineteen Century usually end in the diplomatic direction that the body “be buried in the usual place in the usual way.” In some cases babies who died before being baptized were also interred in such plots as were Highwaymen and thieves who had been executed. In 1806 the notorious Larry Clinch was hanged at a tree near Ballybough Bridge and later buried in the nearby Suicide Plot. During the Eighteenth-Century heyday of nearby Mud Island, gun battles between the Revenue men and the Island’s smuggling community were numerous and bodies were often left strewn along that part of Ballybough Road, inspiring one local balladeer to write “tis a wise man never saw a dead one.” These bodies may also have been buried in the Suicide Plot.

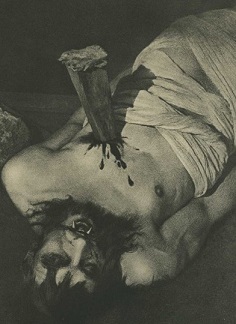

A Felo de Se burial at Midnight.

The only means of avoiding a verdict of Felo de Se was to prove temporary insanity at the time of the “crime.” Because of this the relatives of the wealthy and the famous could usually hold on to the family inheritance courtesy of a competent lawyer or sympathetic doctor. Therefore, it was usually the poor who fell victims of the law and so there is little surviving documentation of cases up to the end of the eighteenth century. However, a surprising number of suicides among soldiers and young women between 1800 to 1823 means we have some idea of how the inquests worked. The latter year saw the first reform of the law, allowing burials at midnight in consecrated ground with a police escort present, but with no religious ceremony permitted. In 1820 members of the regiment from which one unfortunate soldier was found guilty of Felo de Se had attacked the proceedings, rescued the body, and interred their former comrade with full military honors in a local graveyard. The Felo de Se law was finally reformed completely in 1886.

Over time most suicide plots were forgotten but uniquely a rich folklore tradition grew up around Ballybough so that its location remained in the local consciousness. In 1921 Weston St John Joyce would record that local residents in the nineteenth century“would have gone a considerable round rather than pass the unhallowed spot after nightfall.” As late as 1990, the former TD, John Stafford, informed Dail Eireann about the Ballybough location and stated that “it is said that spirits are still in the park beside the Luke Kelly Bridge.” Significantly, the corner location has never been built on probably due to the ever present superstition of the sites contents.

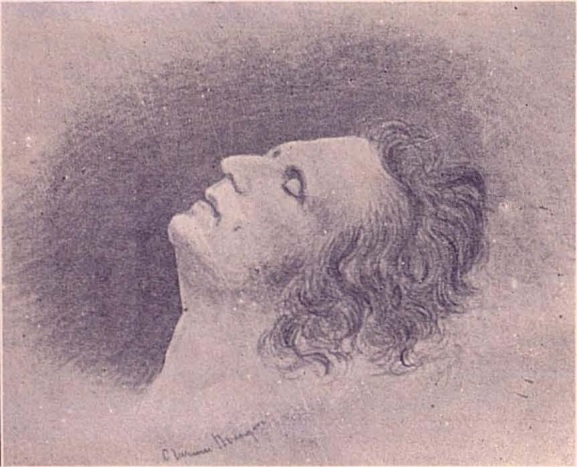

James Clarence Mangan.

Probably its earliest influence on literature came from the poet James Clarence Mangan , most famous for “Dark Rosaleen”. He was part of a literary circle who met at a tavern near the present-day Railway Bridge at No. 23 Ballybough Road.One of Mangan’s earliest surviving works, dating from 1819, was originally titled “Enigma – A Vampire”and was published three years later as “Bleak was the Night” in Grants Almanack. In the poem, Mangan encounters a ghostlike warrior, risen from the dead, of stature “more than a man” clad in “robes of deepest black” with a “blood-red ribbon round his neck,” who by morning light will have returned to a “bloodless corpse.” Mangan often published pieces under a pseudonym, as being “from Mud Island beyond the Bog”, or by “Peter Puff of Mud Island”. A number of his early poems exhibit the same Gothic type of inspirations and imagery.

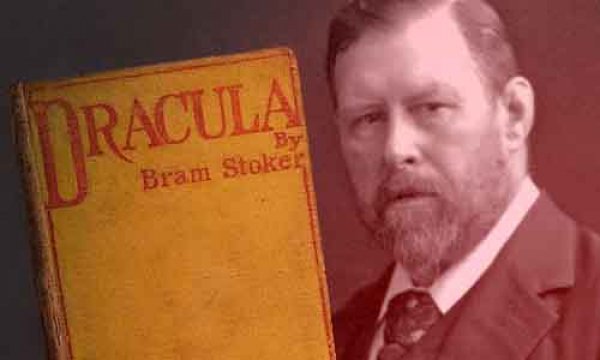

The 7 year old Bram Stoker.

Of Course, the most famous association of the Ballybough Suicide Plot is with Abraham “Bram” Stoker, author of Dracula, who was born at No. 15 The Crescent, Fairview, on the 8th November 1847. Between the age of three and seven Stoker was struck down with a mysterious illness and was bed-ridden for that period. His mother, Charlotte, had a vivid imagination and had grown up in her native Sligo during the 1832 Cholera outbreak. She told her son stories of people burying sick visitors alive in hastily dug pits so as to avoid catching the disease and of her family home being attacked by cholera victims during which a terrified Charlotte apparently cut off an outstretched arm with a single blow of an axe. Dublin had also been affected by the outbreak and stories were current of priests visiting the fever hospital to ensure that their parishioners were actually dead before being buried. A long- standing tradition states that the Suicide Plot was used for Cholera burials during these outbreaks. The Cholera accounts by his mother certainly influenced Stoker’s short story “The Invisible Giant.”

Mummified bodies at St. Mican’s Church, Church Street.

It’s been suggested that Stoker’s first encounter with the “undead” came through visits to the vaults of St. Mican’s on Church Street. At one time many of the mummified bodies were exposed and it was considered good luck to shake hands with “The Crusader” and feel the leathery skin of “The Nun.” There is also a tradition that Charlotte brought him to see the Suicide Plot. Given her fondness for folklore and the macabre and the short distance from their various homes during Stoker’s youth it seems inevitable. The lurid tales of happenings at the Crossroads only minutes from their home would have been an enticing attraction. In the 1850s the Ballybough Road was far superior to that of the North Strand, one writer claiming it was among the best in the country. For many journeys it would have been the most efficient way to where they were travelling and would have brought him past the spot and there was no shortage of locals who could fill him in on its history, no doubt, with plenty of embellishments.

An 1882 newspaper report of Stoker’s heroism.

In 1882 shortly after Stoker and his wife Florence moved to London he leaped from a steamer on the Thames to try and save an elderly former soldier who attempted suicide. Stoker brought him to his home and sent for a Doctor to try and revive him, but he expired on the dining-room table.Stoker now found himself a key witness at a Salo de Fe inquest albeit one which would not conclude with a stake through the heart. However, the various tales he had heard as a child must have come flooding back to him.His wife, who had grown up in No.1 The Crescent, told him she would never live in their Chelsea home again; so they moved. Perhaps, like her husband, she was aware of the stories of the nearby Ballybough Suicide Plot and the Spirits who allegedly roamed near it at night.

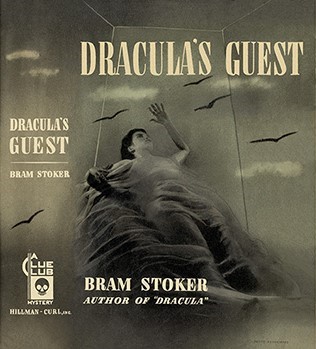

In 1875, while still living in Dublin, Stoker had contemplated a story about a man thinking of suicide but who changed his mind when someone attempted to murder him. His short story, “Dracula’s Guest” published two years after his death in 1914, is believed to have been a chapter from Dracula which he had excised from the final book. In it Stoker specifically refers to the process of a Felo de Se burial, the unnamed hero recalling “the old custom of burying suicides at crossroads”without ceremony and with a stake through the heart.It unequivocally shows he was conversant with the punishment long before he read Emily Gerard’s Transylvanian Superstitions which gave him the added element of garlic for his most famous work. Felo de Se was something which he had first encountered while still a child back home in Dublin when his imagination was fired during rambles around Ballybough.

For comments , clarifications and corrections contact

eastwallhistory@gmail.com