The 25th of April 1916 was the second day of the Easter Rising. After the surprise and confusion of Mondays events the British forces had taking stock and were preparing their response. For the rebel garrison at Stephens Green this response would be deadly. In the early hours of the morning the Green was raked with machine gun and rifle fire from the overlooking Shelbourne Hotel. James Corcoran, was hit in this initial assault and died instantly. He had ‘joined’ the Irish Citizen Army less than 24 hours earlier. This is his story – a North Dock resident, a trade unionist and a late-comer to the Citizen Army, as told by Hugo McGuinness.

The Corcoran’s were small farmers from Brideswell Little, Ballyellis, Cranford, in County Wexford. It has been suggested that there was a family connection with the 1798 Veteran, James Corcoran. Following the Rebellion’s defeat he led a stirring resistance up to 1804 with his small band known as the ‘Babes in the Woods’. Betrayed, they were killed in an ambush by the Kilkenny Yeomanry and Corcoran’s body displayed for some time outside Wexford Gaol as a warning. However it has proved difficult to establish the veracity of this link.

By the late 19th century James Corcoran (senior) and his wife Elizabeth were farming a small holding near Gorey, with James supplementing his income by working as a Blacksmith. There were 11 children in all, two of whom, Bessie and Maryanne both died young. Andrew, the eldest son, followed his father’s profession as farmer and blacksmith and was to inherit the family farm. Two other sons, James and Thomas were to be found professions. James Corcoran, junior, was born in Craanford, Gorey in 1883. Following school he was apprenticed as a Purveyor’s Assistant and by 1901 was working for Michael Byrne, a large scale Provisions Merchant in the Markets Area of Dublin. Byrne was also from Wexford, so the position was probably arranged through family connections. The business had a staff of 7, including apprentices, living over his premises at 25 Mary’s Abbey.

We know very little about this part of Corcoran’s life but it would have consisted of long hours with little freedom available “living over the shop.” His employer was his landlord and his earnings would have been poor, largely consisting of his keep and pocket money. A Grocers Assistants Association had existed since 1863 but they were no match for the more powerful Licensed Vintners and Grocers Association. The Manchester based National Amalgamated Union of Shop Assistants operated in Ireland but it would be 1918 before grocer’s assistants had the type of representation which gave them the confidence to strike for better conditions.

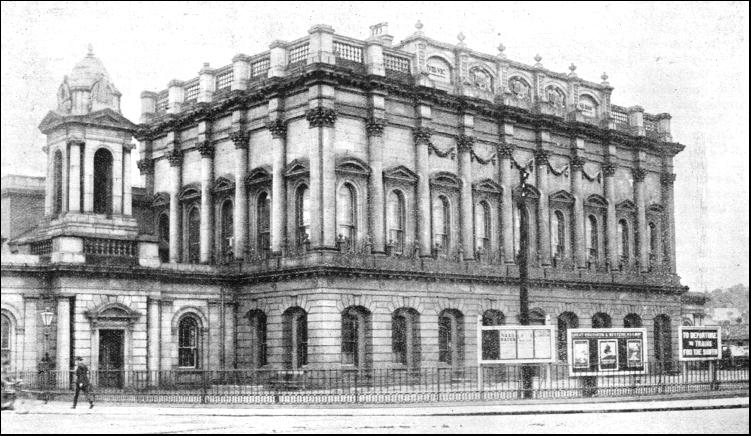

Kingsbridge Station (renamed as Heuston in 1966)

“…wretched conditions of service which existed in Ireland”

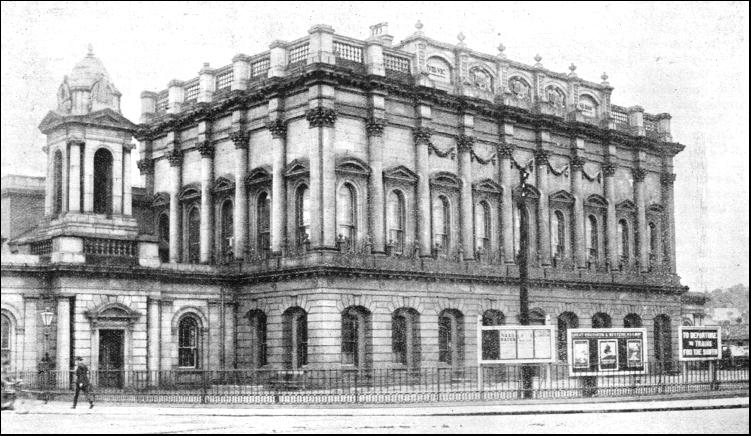

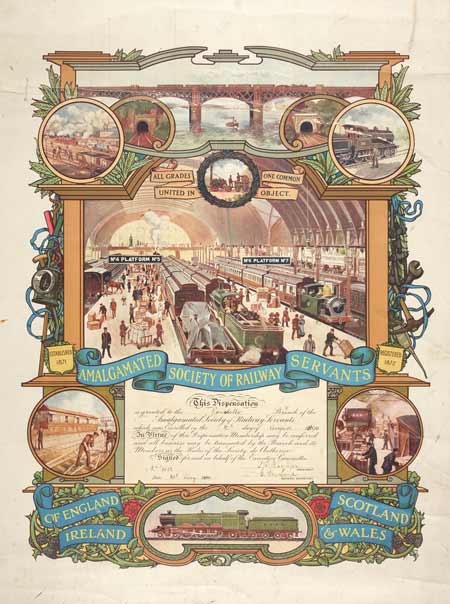

It was probably the chance to earn a decent wage with fixed hours that saw him leave Byrne’s shop and we next encounter him in the records in 1903 when he joined the Kingsbridge Branch of the Amalgamated Railway Servants Union. Corcoran was working as a porter with the Great Southern Railways. It was a turbulent time with the Union taking an aggressive stance against the apathy and indifference of Irish Rail workers. At a meeting at the Trades Hall in Capel Street in July 1905, J. H. Thompson, the Union’s President, spelled out how Irish apathy to the “wretched conditions of service which existed in Ireland” was hampering the efforts of their English co-workers in improving conditions there. He called for a general combination of rail workers pointing out that “all grades of the railway service should join one common union for the benefit of all and for the promotion of the interests of all.” He also pointed out that “they had to consider the safeguard which their children had in the event of the bread-winner being swept away.”

In July 1907 at the Irish Branch of the Union’s AGM in Moran’s Hotel, delegates were gearing up for a general strike over recognition by the Irish Railway companies. While they felt there was room to compromise on hours and wages the unwillingness of the companies to recognise the Union as the representative of the workforce was the cornerstone of all talks. Mr. Murphy of the Kingsbridge Branch claimed that the issue was more with “the interference of under-strappers than of the board of Directors” as it was “almost impossible to get into the Boardroom”. By October the London Daily Chronicle was reporting that the 384 union members, about 90% of the workforce at Kingsbridge were preparing to strike for recognition. It also reported that the members at Inchicore Branch, comprising Firemen and Drivers, were in solidarity with their fellow unionists. The Great Southern Railway Company had begun training Clerks as signalmen in anticipation of the strike but without drivers their operation, as the Union pointed out, was bound to come to a halt. Ultimately the employers gave in and the strike was averted. Corcoran in the meantime had begun working as a carter and left the railways having found employment as a Breadvan driver.

In 1908 he was living at 15 Lower Oriel Street in the North Dock. This was a private house let out in rooms to a number of families. On the 31st August of that year he married Kilkenny woman Margaret Costello. Her recently deceased father, John, had also been a driver, working for the Grand Canal Company. Corcoran obviously had some ambition as he was earning about 35 shillings a week and he moved the short distance to No. 2 Elizabeth Place, off Oriel Street, a 5 roomed house costing 7 shillings per week rent. Some of this was offset by Corcoran’s Brother Thomas (working as a Grocer’s Assistant) and Sister Theresa (working as a house-keeper) moving in with them to share the expense. The Corcoran’s family would quickly grow, with Margaret being born in 1911, James in 1912, and John in 1914. Another child had unfortunately died young.

The strikes of 1911 were international news

“Strikes were in the air at the time…”

1911 saw a series of strikes which involved rail workers and Carters in the North Docks. Troops were stationed on the rail lines and the quays and local school boys were even inspired to strike. Violent incidents including the discharging of firearms occurred in the Sheriff Street and Spencer Dock areas. It was to be an eventful year for Corcoran. On the 26th September that year a dispute broke out between the Operative Bakers and the Master Bakers Association leading to an all out strike in Dublin. Similar strikes broke out in Belfast and London later that year. By October the strike was collapsing and the Unions tried to get as many strikers re-employed as possible but there were no guarantees. Corcoran retained his job but given his union politics and his support for the strike it seems likely that life was difficult for him.

In August 1912 his employment was to change again, this time to the London and North Western Railway. He rejoined the National Union of Railway Servants on the 8th August. The LNWR were a short walk from home, and after the difficulties of the British coal strike and foot and mouth scare earlier in the year, which had seen a major downturn in business, the company was now booming again. Just weeks after he joined, on the 24th of August, the SS Cambera brought in 1000 tourists leaving the cities carmen with a “busy time fulfilling all their engagements.”

LNWR North Wall station

However just over a year later he was to change jobs again, this time to the Midlands North Eastern Railway. This also involved a shift in union membership, to the North Wall branch of the British based National Union of Railwaymen.His membership began on the 11th August 1913, just as the Great lockout was looming. On Saturday 8th September 1913, 180 members of the ITGWU walked out of work at the Midlands Railway at Broadstone and the strike quickly spread to their North Wall depot. The demands were for a minimum wage of £1. Two years earlier in 1911 Irish Railwaymen had struck in sympathy with their English colleagues and it is likely that James Larkin expected that this would be reciprocated, and that the demands of their fellow workers in Ireland in 1913 would be backed. However this support never came. The strike was settled within a few days but by the 15th of the month the company published notices that they would be unable to deliver goods at either Broadstone or North Wall and that customers would have to make their own arrangements due to the unsettled nature of things caused by the general strike. It seems probable that Corcoran was caught up in this as he was dismissed along with other colleagues such as Peter Coates and James Barry, his near neighbours in the North Docks and both members of the Irish Citizen Army. Employment seems to have been irregular but he was working for Lairds, the Scottish Shipping Company at 73 North Wall in May 1914, when his son John was born. Times must have been hard as he was arrested in July 1914 for stealing a pair of boots worth 8/6 and after a week in Mountjoy was released on a fine of 10 shillings.

Corcoran returned to working as a bread van driver, earning £2.10 a week, all of which he gave to his wife to support the family. He seems to have joined the ITGWU at this time and it was union business that brought him to Liberty Hall on the faithful morning of the 24th April 1916. Although Corcoran had several neighbours in both the Volunteers and Citizen Army he isn’t known to have had an association with either organisation. However as he climbed the steps and looked at the mobilisation going on around him it seems he decided to throw in his lot and march behind Michael Mallin to Stephens Green.

“ A cheerful and sad sight”

Initially there was a festive air about the occupation of Stephens Green. Frank Martin of the Royal Irish rifles, recalled seeing the Citizens Army there, but though nothing of it as he assumed they had got permission to camp out over the holiday weekend. Frank Robbins of the ICA describes the first activity carried out here – “With the evacuation of civilians complete, Captain Christopher Poole allocated a company of men to secure each entrance into the Green. While some gates were barricaded with wheelbarrows, gardening implements and park benches, Captain Poole ordered a number of men to dig slit trenches and foxholes covering the main entrances. The company started ‘digging in’, getting out their trenching tools and implements and excavating shallow holes so that they could get below ground level but still have a good firing position.”

Corcoran was involved in digging trenches at the Hume Street end of the park. About midnight on Monday, ICA Private Peter Leddy, stationed at the Bank on the corner of the Green and Merrion Row, noticed a Royal Army Medical Corps Ambulance coming from the direction of Portobello, unloading “men and armaments” into the Shelbourne Hotel. At much the same time Lieutenant Charles William Grant of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers managed to negotiate a machinegun company of the Cavalry Brigade safely through the city to the hotel. It was Grants third trip there that evening. Leddy attempted to make a report to Countess Markievicz “and another officer in the Green but got no satisfaction and was ordered back to his post.” (As this use of the Ambulance was in direct contravention of articles 9 and 10 of the 1906 Geneva Convention it made the medical staff combatants and thus outside the protection of the agreement. At that stage it might have seemed impossible to Markievicz that the British were “not playing the game” and were in breach the rules. However, this turned out to be just one of many such breaches and many eye-witnesses have commented on this. Medical staff were compromised, and this may help to explain the numerous reported attacks by volunteers on Royal Army Medical Corps Staff.)

The British Army view into St Stephens Green

In the early hours of Tuesday morning the attack from the Shelbourne began. Lieutenant Grant recalled it as “a cheerful and sad sight to see the campers scattering and running out the far side of the Green.” As the machineguns barked a number of men fell dead or badly wounded. It’s unlikely that James Corcoran heard the shot which hit him in the back of the neck, killing him instantly. His body remained there until Sunday when he was removed and buried in the poor ground of Glasnevin Cemetery. His body was later re-interred in the Republican plot on the 30th January 1918.

One eye-witness recalls that on Tuesday afternoon “The Citizen Army had evacuated St. Stephen’s Green and a man lay dead over his rifle inside the railings. I was ordered to get back while looking at this man by the British in the Shelbourne Hotel”. He added that Corcoran remained there “…for a whole Week until some charitable men took the body away for burial to Glasnevin on Sunday. I gave evidence of identification in this man’s case for a death certificate.”

“My husband was not taken to any hospital, he was buried from Stephens Green”

Maggie Corcoran was left almost destitute relying on the support of her brother-in-law who still lived at Elizabeth Place and was giving her 30 shillings a week for his keep. She had no immediate family in Dublin and few friends. The American Aid came to her help with a grant of £10 and a weekly allowance of 15 shillings. In 1923 with the advent of the Military Service Pensions Act by the Cosgrave government, Corcoran (as a fatality of the Rising) was classified as an officer and his family received a pension of £90 a year.

Maggie Corcoran and family

James Corcoran was 33 years old when he was killed. His name is recalled in the Republican plot, Glasnevin, alongside Michael Malone, Neill Kerr, and Parick O’Brien on a stone placed there in 1935 by the National Graves Association.

James Corcoran should not be remembered only as a name on a stone. We feel that it is important to put a human face to his story – a story more about working class struggle and trade union activism than simply armed insurrection. There were very many men and women from the North Docks who participated in the revolutionary events in Ireland a century ago. Their involvement was not accidental – it was the reality of their experiences – their working, family and community life- and a desire to change things for the better that motivated them. We are committed to telling these peoples stories in as complete manner as possible, looking at their lives before and after the ‘big events’ of the day. If you have any material that would help with this work – family memories, photos, memorabilia etc please get in touch.

eastwallhistory@gmail.com