The Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Factory

Between 1915 and 1919 the Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Factory operated in Dublin Port. It was established by the Scottish born John Smellie, who was already operating the Dublin Dockyard Company since 1902, his ambitious attempt to establish a ship building industry in the City. Smellie has left a lasting legacy on the local community – unable to find suitable accommodation for his skilled Scottish ship builders, he had acquired land and built his own houses. These 20 unique dwellings at Fairfield Avenue (East Wall) were based on a Glasgow design and seemingly replicated nowhere else in the City, and still stand today. The munitions factory employed almost 200 local women and girls. This is the story of this almost forgotten Dublin Dockland Industry.

Troops at North Wall , August 1914

On 4th August 1914 Great Britain declared war on Germany bringing Ireland into the First World War. The reserves were called up and thousands flocked to the colours. Everyone knew it would be all over by Christmas – except Lord Kitchener, a Kerryman and Minister for War, who suggested they may need to make at least a 3 year plan. Christmas came and went and the war wasn’t over. However, by March 1915 Britain was ready to make it’s big move to end the war by smashing through the German lines and outmanoeuvring them. This came to pass at Neuve Chapelle in France where British forces fired more shells than had been used in the entire Boer War, lost nearly 10,000 troops but made little advance on the German lines. The fall out, led by the Irish born Press Baron Lord Northcliff, put the blame on poor ordinance. The Germans were producing 250,000 shells a week to Britain’s 30,000 and those that were produced by Britain were said to be of poor quality. This lead to a huge reassessment of arms production and while Irish revolutionaries such as Patrick Pearse and James Connolly were thinking “Britain’s difficulty is Ireland opportunity” – the same thought was occurring to Industrialists, Politicians, and even many Trade Unionists throughout Ireland. There was very little industrialisation in the country outside of Belfast and many saw the war and the armaments industry being created as the opportunity to finally industrialise the country, backed by government funding, creating lasting skills and industries when the war was over, and employment, as Lloyd George would later state, for over 50,000 people.

Neuve Chapelle , March 1915

Lobbying began with North Dock MP Alfie Byrne claiming Ireland contributed £15 million in war taxes and got little in return. The Chamber of Commerce in Dublin set up an All Ireland Munitions and Government Supplies Committee which undertook a survey of Dublin’s existing engineering workshops between the 16th and 24th April 1915 and suggested what uses they could be adapted for in order to win war contracts. They met a favourable reception in London, however the existing government fell and a coalition was formed. Their first act was to set up a new powerful department called the Ministry of Munitions who would award all war contracts and direct munitions production for the duration of hostilities. In July the chamber set up the Dublin Armaments Committee, “representative of all trades in the city which it was considered could assist” and organised visits to the War Office, Woolwich Arsenal, and arms manufacturing centres in Birmingham and other cities. The same month Captains R. C. Kelly arrived in Dublin and set up the Ministry of Munitions’ offices at number 32 Nassau Street. Kelly had headed up the North Eastern Armaments Committee in Britain and had shown great skill in maximising resources of the various engineering concerns available.( However in November he went on to be appointed head of recruitment in Ireland and managed to double the figures before returning to London in 1916). Initially there was great optimism, the Chamber claiming that this new industry would boost the economy with the employment of “several hundred hands” and the “distribution of thousands of pounds per week in wages”. They also noted that large orders worth thousands of pounds had been placed with Engineering and other firms in the city. However, of the 1369 contracts offered up to August 1916 only 24 or 1.27% went to Irish companies and most of those went to the Harland and Wolfe Shipyard.

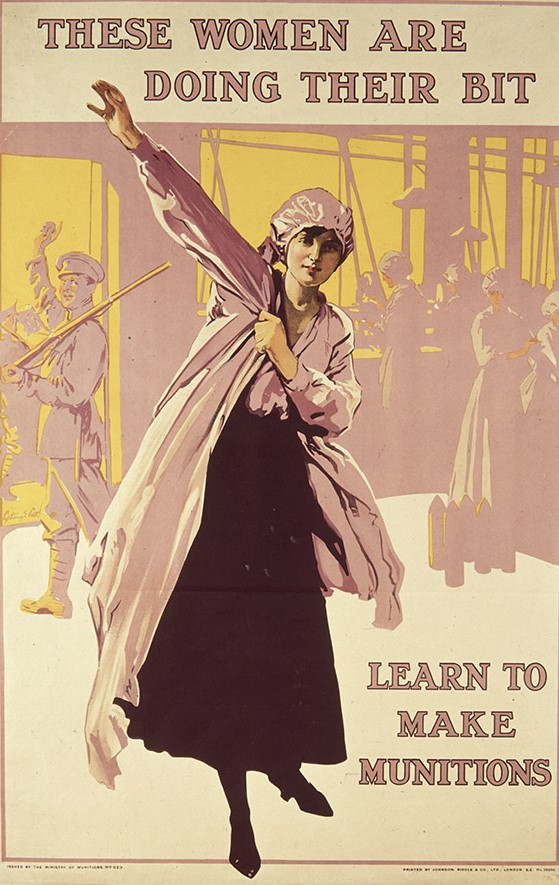

In 1916 The Dublin Chamber of Commerce, commenting on a meeting held with the new ministry, suggested that the results “fell far short of what is due to this country having regard to the expenditure in Great Britain.” Not surprisingly nearly 16,320 Irish people were working in munitions factories in England by 11th May 1917 attracted by persuasive advertising campaigns offering higher wages. Agents of leading manufactures visited Ireland on recruiting drives leading one Limerick writer to comment that local girls believed “money could be picked up on the floors of English Shell Factories as easily as shells on the Irish sea-shore.”

The Ministry of Munitions had the power to nationalise industries which they did with the Irish Rail network in 1917. They could commandeer factories such as breweries for chemical production; they could arbitrate in labour disputes such as the long running strike between the ITGWU and the Dublin Steampacket Company between 1915-’16. They had the power to commandeer raw materials – they bought the entire wool production in Ireland in 1917, they commandeered much of the Irish merchant fleet, and became the largest purchaser of Ulster linen to be used in aircraft manufacture. They were immensely powerful with major powers of compulsion. They also issued licenses to allow workers move between jobs in priority industries. Ordinary labour problems involving individual workers were dealt with during their sittings at the Northern and Southern Police courts in Dublin. However, the Dublin representatives of the Ministry seem to have left a lot to be desired and were a constant source of criticism from Irish business interests. They failed to get a Production Depot operating in Dublin until 1917. This was a central location where Irish made products could be checked locally before being shipped to England, saving enormous expense on shipping if the goods were to be returned as faulty. There was also expert advice available to assist contractors on various aspects of what they were producing. It had been promised in March 1916 but would take a further 12 months to materialise. Curiously enough the Production Depot was located at Oriel House in Westland Row which would play a very sinister role during the War of Independence and Civil War.

For Irish companies War Contracts were survival. As the ministry controlled raw materials, if you weren’t’t producing for the war effort you were likely to go out of business. Building companies adapted to make wooden ammunition boxes, often at break-even prices or at a loss, to avoid bankruptcy. Contracts for a million boxes were awarded to Irish companies after considerable lobbying. Even then manufacturers, having invested capital to secure contracts, and successfully completed orders, often found themselves ignored for further tenders. Others such as the Dublin Dockyard Company found themselves having to pay premium prices for poor quality American steel on the open market the quality of which only became apparent at the end of the manufacturing process. John Smellie, the Scottish born owner and manager of the Dockyard had been astute enough to secure a repairs contract with the Royal Navy as early as September 1914. They were soon producing pontoon bridges, floating targets to train gun crews, fitting ship gun platforms, dept charges, wireless cabins, mine laying appliances, telegraph poles, among other war related work.

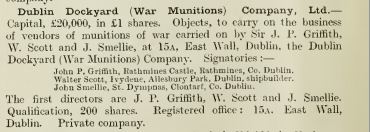

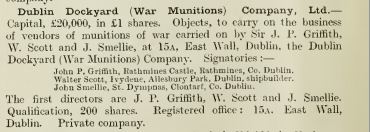

Shell and hand grenade factories had been set up in Belfast early in the war and following all the lobbying efforts it was announced that the government was to set up a National Shell Factory at Park Gate Street in 1915. This was greeted with great enthusiasm and a Captain Fairbairn Downie was brought over to run the enterprise. Downie, from Alnwick in Newcastle, was a skilled engineer and administrator, with a distinguished career in naval and military engineering as well as with Armstrong and Whitworth aircraft manufacturers before the war. Since then he had executed government contracts with various manufacturers in the Far East, South American, Canada, and the USA. He would be promoted to Major before he resigned in January 1918. Progress on the National Shell Factory was slow most of their early employees being engaged in clearing and adapting the buildings. Substantial alterations had to be made to the complex with the provision of shafting and fresh girder work. It took almost a year to hit full production. At much the same time the Lee Arrow Company at Clarke’s Bridge in Cork and the Dublin Dockyard Company independently secured shell making contracts, the Dockyard’s being for 50,000 shells and having raised capital of £20,000 set up the Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Factory at 15a East Wall on a green-field site beside their graving docks in November 1915. The building was wooden in construction with 2 corridors of 4 rows of machines. There were storage rooms at either end for the raw steel bars and the finished shells. The Dockyards had “Priority Establishment” status thus protecting their staff from recruitment; however regulations stated that only 5% of munitions manufacturing staff could be male so 12 girls were recruited and sent to the Vickers Company in Barrow on Furnace for training. They would in turn not only train the rest of the girls recruited for the factory but also the first 50 girls recruited for the National Shell Factory at Park Gate Street.

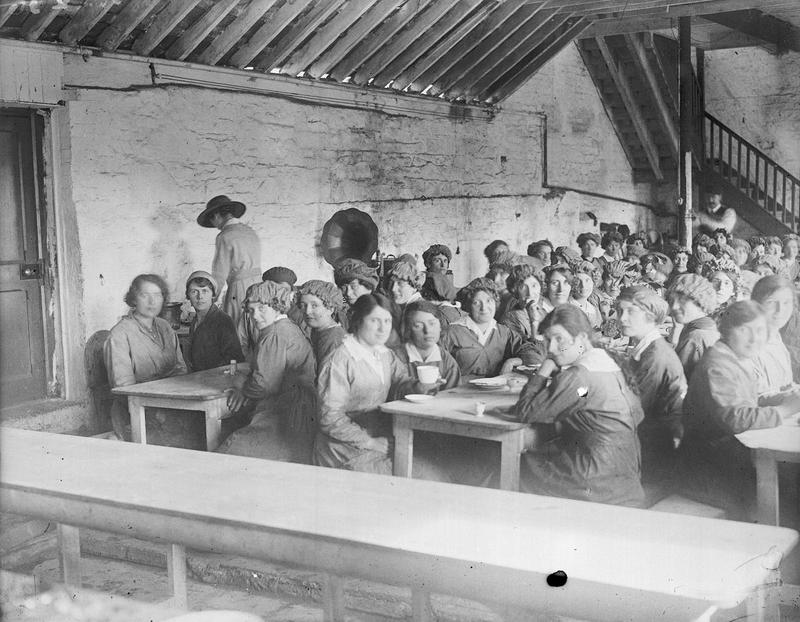

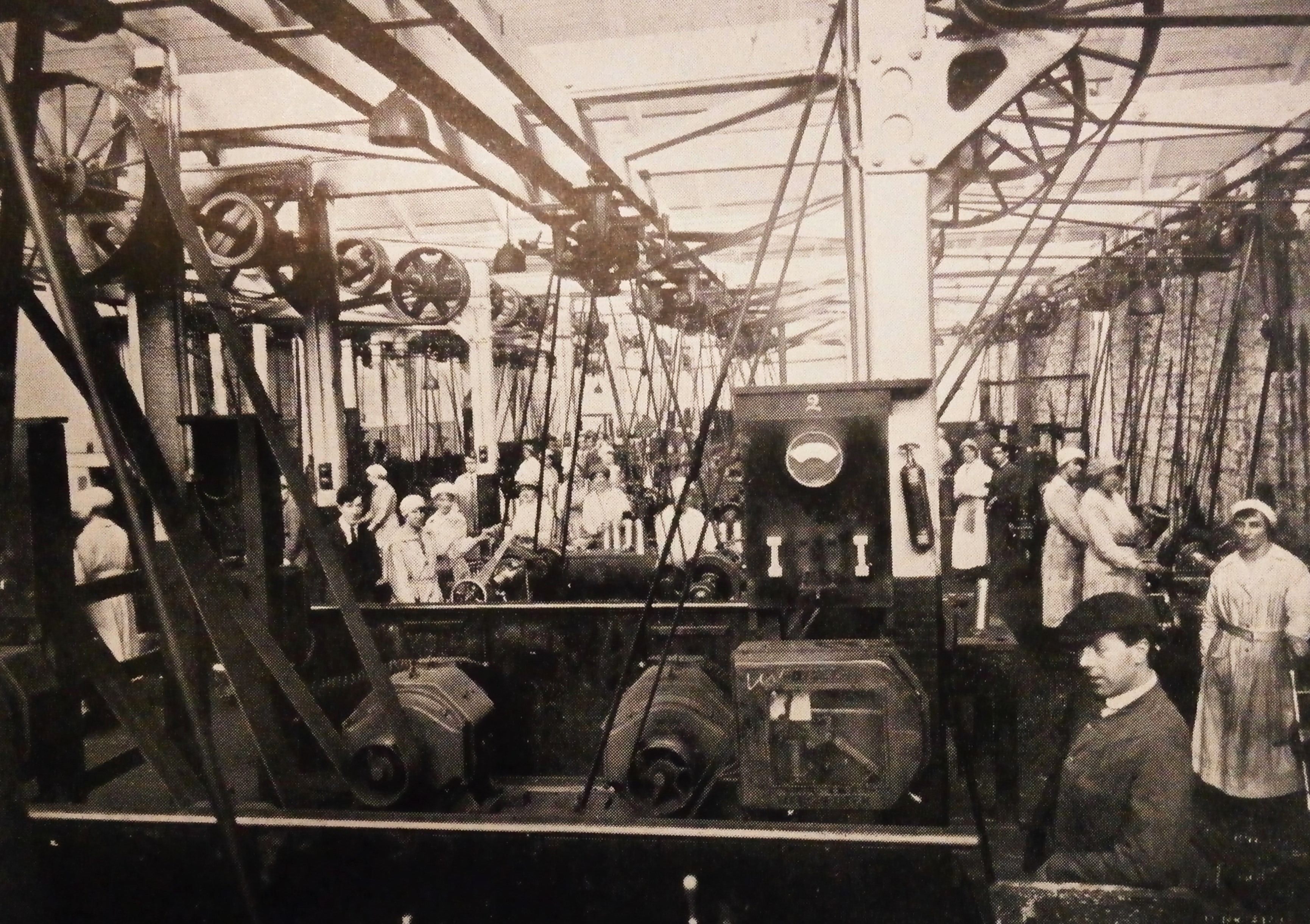

Dublin Dockyard Munitions Workers

While the Dockyard Factory awaited the arrival of the machinery from Manchester they acquired some lathes that were about 50-60 years old and began producing components for the National Shell Factory. The National Factory had ordered machines from Sweden and the USA but as these seemed to take forever to arrive they began a process of commandeering machines from Dublin Engineering works. In particular the Technical Training College at Bolton Street was a major source of equipment, much to the detriment of it’s educational role. The Fuse Factory at the Inchicore Works acquired lathes from the Technical Institute in Cork, leaving a gap in the education of apprentices for several years. The Natioanl factory recruited through the Labour Exchange following a direction from the Board of Trade to relieve some of the 2885 unemployed on the books in Dublin, 1248 of whom were women. The Dockyard Company, on the other hand recruited through personal recommendation, thus most of their girls were local from either the North or South Docks. The National drew staff from a wide area from Dollymount to Chapelizod working 3 shifts in 24 hours. This created great difficulty for them as the Trams didn’t’t start in time for girls on the 6am shift and many had a long walk to work. 20 girls were dismissed in October 1916 for poor time-keeping. The Dockyard Company worked 2 shifts, the recommended standard following experiments at Vickers in 1916, with a target of 2000 shells per week. In a short time they were producing 3000.

Dublin Dockyard Munitions Factory

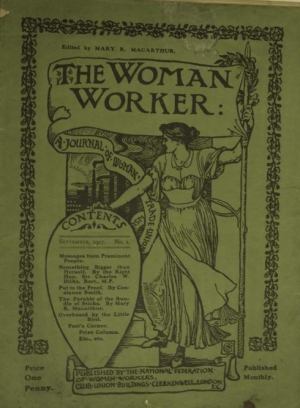

Paper produced by the NFWW

One of the early recruits of the National Factory was Christine “Molly” Maguire. Born in London to Irish Parents, she had been schooled in Belfast, and as labour problems grew in the factory Maguire made contact with the British National Federation of Women’s Workers and began to unionise the shop. The NFWW was aware of the Irish Women Workers Union (IWWU) but they felt (and the IWWU agreed) that they were better placed to represent women in the munitions Industry. Maguire was made National Organizer and spread the Union not only to the Dockyard Factory but also to the National Factories which had opened at Cork and Galway, and the Cartridge Factory at Waterford. She was so successful that she returned to England to work for the Union as an activist there. With the near collapse of the IWWU after the 1916 Rising and with so many of it’s key people in prison, Irish born Helena Flowers, the Assistant Secretary of the NFWW, spent much of 1917 – 18 in Ireland putting the Union on a sound basis, spreading their recruitment into Jam Factories and other poorly paying areas employing women for as little as 4 shillings per week. Aware that there was opposition to British Unions coming across and starting up for workers generally the NFWW claimed that “ a unanimous decision was arrived at with responsible sections of thought in Dublin that the munitions workers occupied a different position from the workers in the ordinary industries and should be organised into a Branch of the National Federation of Women Workers as they felt that without the strength of the Federation behind them, little could be done to secure equality of treatment for the workers in the Irish National Shell Factories.” In March 1916, twelve controlled establishments in Ireland had been referred to the Ministry of Munitions with regard to women’s wages. According to the official Ministry History nothing was done following representations to the ministry by the Engineering Employers Federation in relation to the lower cost of living in Ireland during negotiation over men’s wage increases later that year. In July the ministry specifically exempted 11 Irish establishments thus allowing them to pay below the general British rate. In May 1917 the union secured an agreement with the ministry to place the wages of Irish women in the munitions industry on an equal footing with their British counterparts, an increase from 18 to 24 shillings per week and from 23 to 30 shillings for night shift work. Only two soap factories on the controlled register were exempted. In November 1917 a further increase of 5 shillings was awarded by the ministry and immediately the Engineering Federation lobbied for an Irish exemption. This was refused on the basis that these awards “must apply to Irish firms.” Following a strike and lock out of women at the National Factory in September 1918 they achieved the right to have women shop stewards negotiate on behalf of women workers. Then in 1919 with the munitions factories closing and the IWWU back on it’s feet, they handed their entire operation over to Louis Bennet the new leader of the IWWU.

The Irish Women Workers Union at Liberty Hall

At full production the National Factory employed 809 (of whom 531 were women), the Docklands Company just 200. As the employment of women was somewhat novel, the ministry produced numerous advisory booklets for would be manufacturers which examined such diverse subjects as the nutritional health needs of women workers, factory ergonomics, and guidelines for the efficient design and management of a staff canteen. The Women’s National Health Association of Ireland produced a booklet on “War and the Food of the Dublin Labourer” showing up the deficiencies of the normal diet for industrial work and how to correct it. A report by Dr. Stanley Kent on “Industrial Fatigue” led to the decision that the factories should only work 6 days a week as workers “resting on the seventh” were “capable of longer and sustained effort” and had much higher productivity than those who worked the full week without a break. The Docklands factory was unique in Ireland being the only munitions factory built on a green-field site. The Directors had visited several private operations in England in order to find “the best features of each” which would be incorporated into the Docklands project. The timber design and saw-tooth roof admitted “an abundance of light” and all the starting and stopping gears of the machines were standardised in order to minimise accidents. By the end of the war their most common industrial accident was an occasional finger injury.

The Dublin Dockyard shipbuilders – with steamer in Graving dock

Shipyard – looking towards Alexandra Basin .

Perhaps the best compliment to the early success of the Dockyard Factory was that the Port and Docks Board, seeing a downturn in business decided they needed to shed 200 jobs. They sought to channel these into munitions production. The Board felt that their engineering works could be easily converted to shell manufacturing and arrangements were set up to visit the National Factory in Parkgate Street as well as the Fuse Factory at the Inchicore Works and George Watt’s Engineering Works at Bridgefoot Street between February and March 1916. The ministry found that the Port and Docks Plant was “unsuitable for munitions work”, however the Board subsequently offered to supply the floor space and electric power from their power station at “a favourable rate” if the ministry would supply the plant and machinery. This was turned down. The board had already given a similar deal for power supply to the dockyard factory. By the end of 1916 they found to be hugely underestimated the cost involved and began renegotiating the arrangement towards the end of that year.

A contemporary description of the docklands factory described how the girls appeared to enjoy their employment. The writer claimed that modern machines required “delicate handling” or “skill rather than muscle” and the girls being of “superior order” had taken an “intelligent interest” in the work they were turning out. Smellie himself recalled that “the 200 girls employed soon became highly efficient, and were quick in adapting themselves to machine work, and to all the engineering operations of shell turning, including working to gauge limits of but one or two thousandths of an inch.” He Claimed “It was perfectly amazing to note with what deftness of hand and eye a cut was made so accurate in judgement as to satisfy forthwith the limit gauges without resort to the usual trial and error of cut upon cut.”

Labour problems at the National were constant with several strikes over non-payment of war bonuses and conditions. Captain Downie was known for his diplomacy and skill in labour problems and seemed to have a real bond with the women workers. His resignation early in 1918 came as he was increasingly frustrated by elements at the ministry in London in his attempts to promote and increase Ireland’s contribution to the War effort. He was attempting to establish an aircraft manufacturing plant at Celbridge when he resigned. Emmet O’Connor claims this was due to Unionist and British employers conspiring to “freeze nationalist Ireland out of lucrative war contracts” However there may have been a more sinister element to their labour problems. Joe Good, one of a number of members of the IRA including Sam Reilly and Joe Leonard who would work at the National Factory in 1918, claimed it was their policy to “get the greatest possible amount of wages whilst doing the least possible amount of work – without getting fired.”

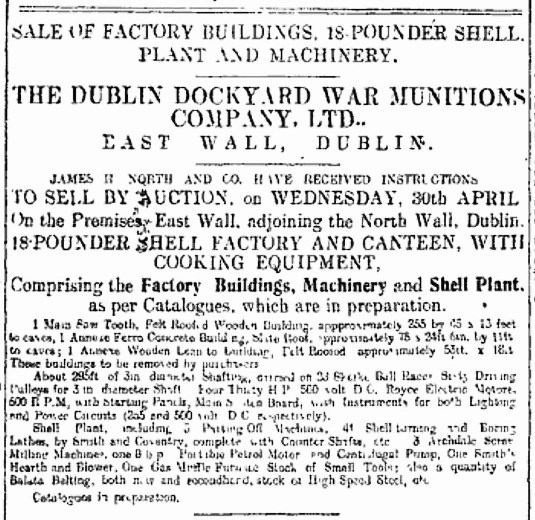

Canteen at National Shell Factory , Parkgate Street

Canteen at Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Company , Dublin Port

The National’s canteen was run by a mix of volunteer and paid labour and rarely functioned during the nightshift leading to claims that workers couldn’t even get a cup of tea during their shift. At least 5 workers died in work related accidents, whereas the Dockyard Company was only affected by one strike and that was an illegal one involving 15 apprentices who seemed to have poor records in time-keeping. The Ministry of Munitions intervened before it could spread and effect production among the munitions workers. The most serious accident experienced by the dockyard factory was when a single girl lost a finger when it was caught in a lathe. The streamlined design meant there was a minimum handling of the shells and a steady flow towards the end of the production line.

Economics was probably the main motivator for the Munitions Factory girls. While there was a feeling that Irish workers should be cheaper than their English colleagues and women work for less than men, the English rates had been widely reported in the media and created a sense of expectation among would-be recruits. The basic rate was £1 per week for girls over 18 (reduced to 15s if work was stopped for reasons such as air-raids etc). After a four week qualifying period a complex productivity scheme kicked in. For most girls the economic freedom this brought was life changing. The sudden increase of disposable income among the Munitions Factory girls was enough to attract cosmetics companies such as Pomeroy Skin food, Ven Yusa Oxigen Face Cream, and the Oatine Company to distribute their products, targeted at munitions factory workers, in Ireland. Sean O’Casey also found the local impact of the factory significant enough to mention it in his play “The Silver Tassie”, where one character is said to have plenty of money she earned working there.

John Smellie, manager of the Dockyard, claimed that many of the girls had fathers, uncles, brothers, or neighbours, serving at the front and had read letters sent back home telling how shells had exploded in the hands of gun-crews due to poor manufacture. For many it was personal, the high standards of their work, would keep their families alive. During the Easter Rising the girls at the National Shell Factory all reported for work and despite heavy fighting produced 800 shells during Easter Week. Mrs Ryan, a district Nurse writing in the State of Public Health Report for 1916 claimed that many women nursing new-born babies chose to work in the shell factories to stretch family incomes and meet the extra expenses involved. However, a curious case involved 20 Irish girls working at a shell factory in Hereford in England in 1917 saw them dismissed and sent home for destroying moral at the Factory. The girls sang Sinn Fein and republican songs all day long and cast aspersions on the “Tommies” at the front. The English girls began to wear Red and Blue colours to which the Irish girls responded by wearing green, white and orange. The episode culminated in a pitched battle at the local train station one Friday evening and the Irish girls were shown the door in order to restore peace and productivity. Some echo of this can be seen in a photograph of the National Factory where what appears to be a Republican Flag sits beside a Union Jack to inspire the female workers. Interestingly, Fianna member Gary Holohan, who worked in the Power Plant at the Docks, stated that many who lost their jobs at the Docks after the 1916 Rising found employment at the Dockyard Munitions Factory afterwards.

A harp flag can be seen here at National Shell Factory Parkgate Street

Unlike the National Shell Factory, the operation in the docklands was shut down during the Rising. As the British Army took control of the area they dismissed all but essential staff needed to operate the port. The electricity supply, provided by the Docklands Power plant, appears to have been sabotaged during the Rising so it would have been impossible to work anyway. The infamous police undercover agent ‘Chalk’ had reported in April 1916 that four members of the Citizen Army were working at the National Shell Factory in Parkgate Street as labourers. These would appear to have been members of the Kimmage Garrison Joe Vize, Matt and Joe Furlong, and another volunteer named Moloney who had all come over from London. About a week before the Rising Vize walked into work smoking a pipe which he refused to put out. He was instantly dismissed. The others then walked out in sympathy with him. They were surrounded by armed guards but were not intimidated by the bayonet’s being thrust at them, and they simply continued out of the factory. The soldiers didn’t’t know what to do next. All were called up before a munitions employment tribunal but the Rising intervened before any action could be taken. Significant numbers of Volunteers and Citizen Army men worked in the Dublin Dockyard Company and Dublin Port generally so it’s likely that there was a similar infiltration of the Dockyard Munitions Factory in the run up to the Rising, though we have yet to see evidence of this.

A total of 648,150 shells were produced by the Dockland Company with much of the component parts coming from smaller workshops in the Dublin area. Each of the girls at the Dockyard Factory was on a personal bonus and according to the directors took a personal interest in maintaining high standards of production. For girls such as Florence Lea from Sandymount it was life changing. She went from a Dress-makers apprentice on 2 shilling per week to a munitions worker earning 50 shillings for a 48 hour week by 1918. Similarly 16 year old Mary Johnson from St Mary’s Road, East Wall, not only found earning a man’s wages gave her independence but allowed her to make a significant contribution to the family household budget as the cheap nutritional meals provided at the Dockyard factory significantly contributed to her disposable income. During World War II when times were bad in Dublin she moved to Birmingham to work in munitions as an experienced veteran along with others from the community. (Perhaps it was a new sense of economic freedom during these early years that saw her pursue a career as a Tivoli dancer also too).

Mary Johnson (to right of photo)- Munitions Worker

Mary Johnson – Tivoli dancer

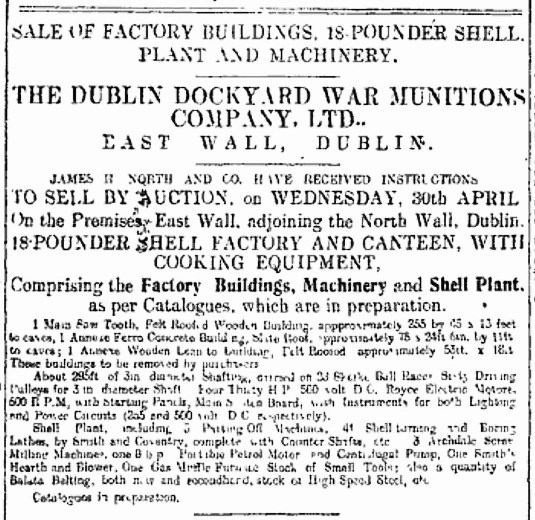

In April 1919 with the war at an end the Dockyard Factory closed, the girls were laid off, and the factory and it‘s contents put up for auction on the 30th April. The other factories in Dublin, Cork, Galway, and Waterford followed over the ensuing months. Attempts to buy out the factories as going concerns were rejected and the equipment sold off piece by piece at auction. Smellie had actually tried to offer his factory as a going concern but there were no takers. The machinery was sold as scrap for £1,600, about a tenth of their cost. The Factory itself was withdrawn for sale and broken up to be recycled. The inventories of the National Factories were widely advertised throughout Lancashire, Yorkshire, and other counties in Britain and much of the machinery left the country. Despite all the lobbying and arm-twisting by Irish Politicians and Business Groups the munitions industries impact on the Irish Economy was short-lived. As the Secretary of the All Ireland Munitions and Government Supplies Committee, Edward J. Riordan put it, “the eyes of Irish Businessmen were opened to the hopelessness of their expecting to receive anything like fair-play from English officials either high or low.”

For John Smellie, whatever patriotic motives he may have had, the munitions factory guaranteed the survival of his shipbuilding business during lean times. As the only privately built factory in Ireland, he was prepared to take on new practices to make the business work. But he wasn’t sentimental. For all the innovation in his wooden saw-toothed factory, it was easily dismantled and sold off or reused and the land handed back to the Port and Docks Board. His was the first factory to close and his plant and machinery sold off before the National Factories had shut their doors. He was a realist and didn’t look around for alternative uses.

Aside from the women who for a few brief years saw their working status enhanced and their right and ability to represent themselves recognised, the main beneficiaries of the short-lived munitions industry were arguably the IRA who used the factories as a training ground for operations such as the underground bomb and hand grenade factory set up at 198 Parnell Street in 1919, a number of whose staff were also employed at Parkgate Street. The training and experience they had received would prove extremely useful as the War of Independence got underway. Even some of the equipment used at Parkgate was bought by the IRA during it’s closing down sale to equip their deadly new enterprise.

Inside the Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Company

If you have any clarifications, corrections or additional information please contact us. We are particularly anxious to hear from family members of women (or the small number of men) who were involved with the Munitions Industry. All contributions or assistance will be fully acknowledged and credited.

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

We would like to thank all those who helped compile this feature, including the Dublin Dockworkers Preservation Society, the Sean O’Casey Theatre and the Ringsend and Irishtown Community Centre who helped us host two public talks on the topic. Thanks to the Pat, Paul and all the O’Brien’s for the family material on Mary Johnson, and to Ronan Waide for sourcing an important detail relating to the equipment sell off. Much appreciated.