“A tough Dock Labourer, pugnacious and voluble…”

On the 16th April 1916 an Irish Republican flag was flown for the first time over Liberty Hall. It was a hugely symbolic ceremony , a message of defiance and a signal of intent by the Irish Citizen Army. Amongst those caught up in the excitement and emotion of the day was Tom Daly. In the second instalment of a two part feature, Hugo McGuinness continues the story of “Blackguard” Tom Daly. ( See part one here -http://eastwallforall.ie/?p=2261 ) A North Dock resident, ITGWU member and Citizen Army volunteer, Daly was acquitted of murdering a blackleg during the Lockout , but jailed for assaulting two scabs. We continue his story in 1915 after he had been released from jail, and was working at Croydon Park, Marino, which was rented by the union.

A poachers luck

Tom immediately threw himself back into the activities of the Citizen Army. Fellow ICA man James O’Shea recalled how Daly would go on poaching expeditions to Saint Margaret’s in Finglas accompanied by members of the ICA. On one of these in 1915 Daly’s group, which included Richard Corbally ( a carter from the North Dock) discovered a Royal Irish Constabulary explosives store in an underground bunker. According to O’Shea, the men “were poaching in a field away from the roads when they came upon a peculiar small building. It had two iron gates. Its roof seemed grass-grown and very little above the level of the field. After looking and examining it for some time a herd came along and told them to make themselves scarce as it was full of explosives belonging to R.I.C. The lads pretended to be scared and cleared out of the field but watched the herd until he went away. They then came back and had a good look and when they arrived in the city they told James Connolly.” This information led James Connolly dispatching a squad (under Mick Kelly) to raid the store. The building was made of concrete and reinforced steel, and despite their best efforts they were unable to relieve it of its contents. According to O’Shea , there was “a great sensation a week after when the R.I.C. discovered that their pet dump had been attacked”.

“A hell of a time from the grim Jim Connolly”

By March 1916 everyone knew Rebellion was in the air. For a number of months William Partridge had suggested the idea of raising an uncrowned harped flag over Liberty Hall. James Connolly was unsure but was eventually persuaded of the symbolism of such a flag flying over one of the most public buildings in Dublin , which Irishmen in the British Army Soldiers would pass as they marched to the docks to embark for the war in France. The pages of the Workers Republic announced that on Sunday the 16th April “the green flag of Ireland will be solemnly hoisted over Liberty Hall as the symbol of our faith in freedom, and as a token to all the world that the working class of Dublin stands for the cause of Ireland, and the cause of Ireland is the cause of a separate and distinct nationality”. Molly O‘Reilly, a young member of the Women’s Workers Union was chosen to raise the flag which Connolly called “the sacred emblem of Ireland’s unconquered soul.” A full mobilisation of the Citizen Army was undertaken at Beresford Place and a huge crowd gathered. According to the account in The Workers Republic:

“All Beresford Square was packed, Butt Bridge and Tara Street were as a sea of upturned faces. All the north-side of the Quays up to O’Connell Bridge itself was impassable owing to the vast multitude of eager, sympathetic onlookers.

Amid the massed ranks of the men, women, and boys of the Citizen Army, Molly entered Liberty Hall, reappearing on the roof and “with a quick graceful movement of her hand, unloosed the lanyard and THE FLAG OF IRELAND fluttered out upon the breeze.” The reaction, according to the report was astonishing. “Over the Square, across Butt Bridge, in all the adjoining streets, along the quays, amid the dense mass upon O’Connell Bridge, Westmoreland Street and D’Olier Street corners, everywhere the people burst out in one joyous delirious shout of welcome and triumph, hats and handkerchiefs fiercely waved, tears of emotion coursed freely down the cheeks of strong rough men and women became hysterical with excitement.”

James O’Shea, among the rank of the assembled soldiers of the Citizen Army recalled “men, old and middle aged, and a lot of women were crying. I knew then that it was not in vain as they all knew what was meant by the hoisting of the flag.” The Citizen Army then paraded to the Railway side of Beresford Place, and then, amid the ecstatic response of the crowd as they were being dismissed, a shot rang out. Tom Daly, overcome by the emotion of the ceremony, had in his enthusiasm, “let fly.” Connolly was livid and instigated the first ever Court Martial within the Citizen Army. In his closing remarks o the Army he had told them “this is your barracks and you will not leave it until you are called to defend the flag hoisted today. “ He was furious at such a lack of discipline. According to O’Shea, Daly got “a hell of a time from the grim Jim Connolly.”

“We hereby proclaim the Irish Republic…”

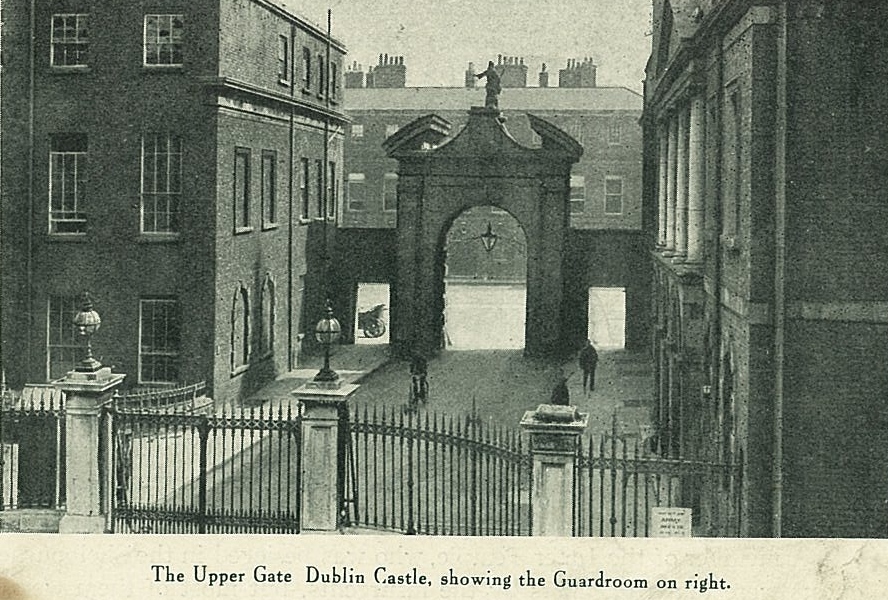

Towards the end of 1915 the Citizen Army was reorganized into sections for mobilisation purposes. Tom Daly was assigned No. 68 and placed in the Gloucester Street, No. 5 Section. The roles of the various units of the Citizen Army in the Rebellion of 1916 had been designated in the run up to Easter Week. Tom Kain, Chief Mobilisation Officer, was to lead a small team, largely composed of the Gloucester Street Section, to take the City Treasurer’s Offices of the Municipal Buildings (now the Rates Office of Dublin City Council). However, on the morning of the 24th April 1916 it was obvious that many ICA members had either not got the call or had failed to respond. The man expected to lead the attack on Dublin Castle failed to show and plans quickly changed. Tom Kain was ordered to attack the Main Guardroom, just inside the gates, and go no further. As the Citizen Army lead by Captain Sean Connolly reached the Castle Street entrance they were confronted by a policeman at the gates who was promptly shot. This sudden violence seemed to cause great confusion, with many of the Citizen Army men opening fire. Kain, urged on by Connolly, then rushed his through the gate and towards the Main Guard. This group included Tom Daly , along with a team of James Seery (No. 188), Philip O’Leary (No. 105), Christy Brady (No. 65) and George Connolly. Seery was in the North Wall Section of the ICA. Christy Brady , from Foley Street, would die from T.B the following year. George Connolly was in the ICA Boys Corps(under Walter Carpenter) and had spent the morning delivering dispatches. Unable to find his section at Liberty Hall he had fallen in with his older brother Sean and marched towards the Castle. The others were all from the Gloucester Street Section.

A homemade hand grenade was thrown through the window of the Main Guard room but it failed to explode. However it caused enough confusion to make the sentry on guard panic and run for cover rather than return fire. George Connolly rushed into the building after him and found the occupants lying at ease, some smoking, some on their beds, unaware of what was about to happen. According to Kain, who followed Connolly into the building, they found 5 men with their hands over their heads who had been “scared into throwing down their arms and giving us the signal of surrender.” They then set to digging in and creating a defensive position. Their prisoners, who turned out to be Irishmen in Irish Regiments in the British Service, were tied up, and the small group began barricading the windows with bedding and furniture. One of their prisoners was kept free and tasked with getting the kettle on for some tea – a task he attacked with some relish. Tom Daly and the others then set too to try and dig a defensible position within the building against a possible machine gun attack by breaking up the floor. They had assumed it would be wood but it turned out to be solid concrete. Armed with just bayonets and axes they made little progress. They soon realised the limitations of their position. There was a single loophole from which they could see outside or try and defend themselves from attack. All around them they could hear the sound of machineguns attacking the City Hall. They were unaware that their group had been forgotten after Sean Connolly and his second in command John Reilly had been killed in the first hours of the fighting. By now large numbers of British troops had arrived and the ICA garrison was heavily outnumbered.

No tea or biscuits – Captured !

By evening Kain began to assess the situation. They could hear soldiers and fighting all around them with no idea whether they were friend or foe. Earlier they had secured an exit through a door in a backroom and once they were informed by their tea making prisoner that their water supply had run out they knew their position was hopeless. Shortly afterwards ,the sound of battering rams at the door of the Main Guard could be heard. Kain took the decision to evacuate. James Seery was sent for supplies but was unable to return, while George Connolly was sent out to scout around and find out what was happening. Tom Daly, along with Kain, Christy Brady and Philip O’Leary made their way to a tenement at No. 12 Castle Street. They entered the cellar and immediately set to digging their way through the adjacent buildings, hoping to reach the top of the street where they could exit and join the Jacobs Garrison. It was difficult and dangerous work, as they could hear troops in the rooms above them.

Kain then realised that the mobilisation books of the Citizen Army were in his pocket , and quickly hid them within a pipe in the cellar (Kain and Frank Robbins retrieved them a number of years later, sometime in the late 1920′s). The tunnelling attempt continued until troops above became alerted to their presence ,dug up the floorboards and arrested the four men.

Gaining the “Blackguard” nickname

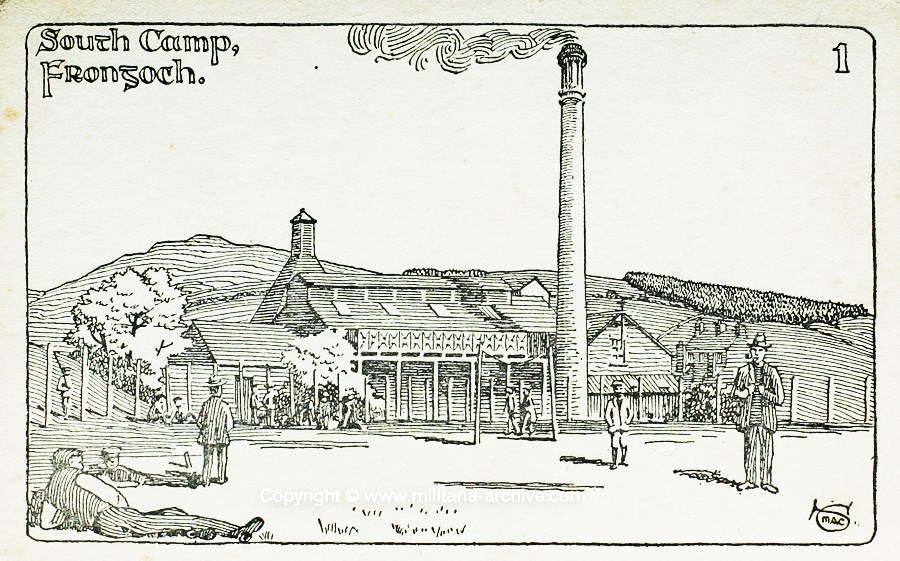

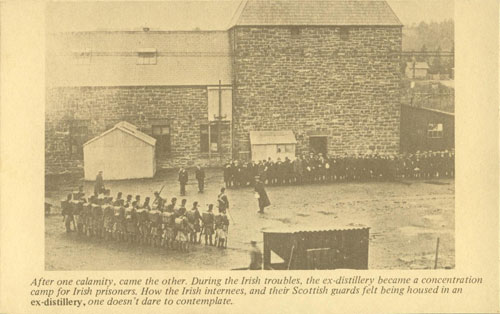

After some time at Richmond Barracks Daly was deported to Lewes Prison in England on the 20th May 1916. Some weeks later he took up residence at Frongoch internment camp in Wales as prisoner No. 100 in the Southern Camp. Joe Lawless (an Irish Volunteer , who had fought at Ashbourne) knew Daly at Frongoch ,describing him as “a tough Dock Labourer, pugnacious and voluble.” For Thomas Doyle, an IRB organizer from Enniscorthy, Daly was “a hard top.” He recalled how no matter how cold the weather was Daly could be found walking about with nothing on him but his shirt and trousers held up by a belt. Daly seems to have done his best to lift the spirits in the Southern Camp. He had a good sense of humour and Joe Lawless recalled an incident involving one of the prisoners who was an artist in the camp. Several inmates had set up a painting studio and it was common for prisoners to wander in to have a look at their paintings. One day Daly dropped in on his way back from the mess hall after dinner and stood in the doorway “in open-mouthed wonder” at the artist’s skill. Conscious of Daly’s presence the Artist asked him for his opinion, whereupon Daly handed him his enamel dinner plate and said “here, would you paint me a bloody steak on that?” It seems to have been from this period that he got the nickname “The Blackguard Daly”, although according to Joe Good it was a term always used with affection.

Chief RAT CATCHER for a prison camp

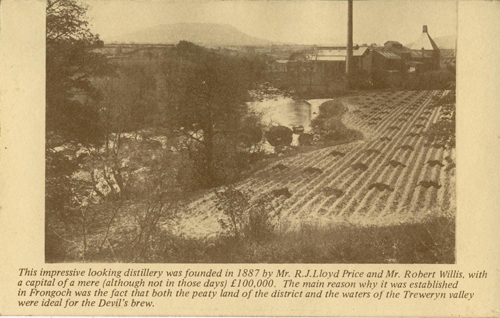

It was a constant source of irony to the inmates that the Welsh name Frongoch was pronounced the same as the Gaelic Francach meaning a rat and the old brewery which contained the Southern Camp was full of them. Daly soon (became the unofficial rat-catcher of Frongoch. On occasions he would take one under his shirt when he went for a stroll around the yard and on seeing the Camp commander’s dog, call it over, and give it the rat. The Guards found it disgusting and tended to leave Daly alone so it may have been a ruse to pass on messages or carry contraband. Usually he would place the rats in an old sack and then gas them using sulphur candles and cremate them in the boiler-room. However he developed a bizarre form of entertainment which was known as Daly’s Circus in which his freshly caught rats were the stars. It seems when he caught large rats they were held back and then he would form a circle of benches in the mess hall to make an auditorium and with the assistance of one of the inmates place the rat in an old sock and tie it’s tail to a piece of string. The rat was then let loose under Daly’s shirt and after some time he would pull the rat out and reveal it’s bite-marks on his chest. He had razor sharp teeth described as “Dracula-like” and on releasing the rat from the sock he would bite it’s head off and let the blood drip down his chin.

“No work today! We are Trade Unionists… “

Many of the Trade Union leaders in Dublin had been arrested after the Rising including William O’Brian who was interned for a time at Frongoch. A policy of non-compliance by the prisoners was instigated in the camp in relation to any work outside of cleaning out their own quarters. Because of its isolated position there were no proper roads into the camp, and it was decided to use the inmates to build one. The Prisoner Executive decided to protest but a new law had come in which meant prisoners could receive an extra 10 years on their sentence if they refused duty. O’Brien was approached to see if he could persuade the Citizen Army men to refuse to work on the road as the Volunteers were afraid of the consequences. Noticing Daly in the yard, O’Brien remembered him from the Thomas Harten Trial and decided he was the right man. The following morning when the road building team was called for Daly and 5 other ICA men stepped forward. Then Daly announced “No work today! We are Trade Unionists and we demand Trade Union wages in future.” Frongoch was now officially on strike. Daly and his team were given 4 days in the guardhouse on bread and water but the road-building scheme was dropped.

“Whatever you say, say nothing”

Many of the prisoners in Frongoch were part of the Kimmage Garrison – second generation Irishmen born in London, Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow. Because these men would have come under the conscription act and been liable to serve in the British Army it was decided that nobody would answer to their name and identify themselves in order to protect them. This was known as the “No name no numbers Strike.” This was to have heartbreaking consequences for Daly . His wife, Rosanna died on the 17th November 1916. Tom was one of those involved in the strike and had not been answering to his name when called, so cruelly a notice was simply pinned to the notice board of the camp. Under normal circumstances, a prisoner would be permitted to send a telegram to his family, and Daly would have been liable for parole to attend the funeral. A Telegram signed Daly was presented by one of the men with instructions for Dalys brother to make the funeral arrangements and take care of the children. The Camp commandant refused to send it as Daly did not hand it in personally and identify himself. Joe Good, a london born member of the Kimmage Garrison, recalled Daly’s “extraordinary loyalty.” Despite encouragement by Michael Collins to “assert his identity and take the privilege of returning to Dublin” he remained steadfast in his refusal. He told Good he feared it might “weaken us in any way so he would not do it.” Volunteers such as Patrick Colgan would recall being impressed and inspired by Daly’s ”character” during the episode. Irish MPs Alfie Byrne and Laurence Ginnell took up the case asking questions in the British House of Parliament which were to lead into an investigation by the Home Secretary Sir George Cave. On the 24th December Daly was released from Frongoch and finally returned to Dublin as part of the general release of prisoners. His stoic refusal to give his name having made some contribution towards their release.

Return to East Wall

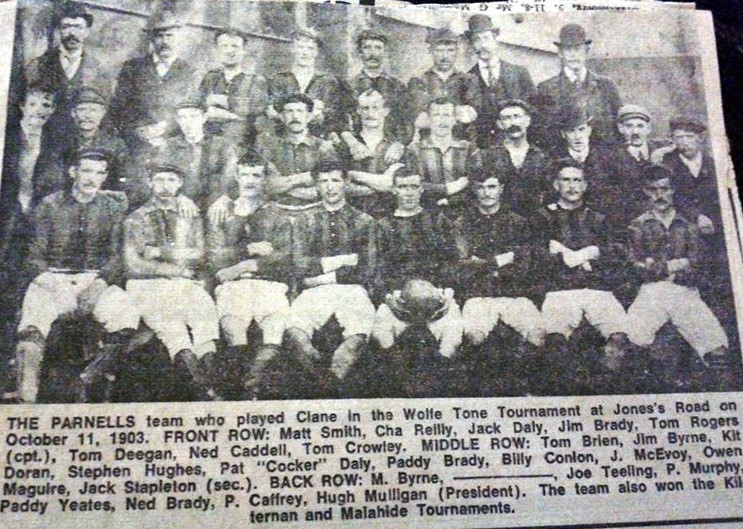

On his release from Frongoch, Daly returned to his brother’s house at Church Road, East Wall. Patrick, known as “Cocker” Daly was a legendary three time All Ireland winning Gaelic Footballer, and had taken his brother’s children in after the death of their mother. On the 16th April 1917 Tom re- married a widow, Margaret Moore, and returned to working on the Docks. He never rejoined the Citizen’s Army, however his brother “Cocker”, who also worked on the Docks, was involved in the procurement of arms in raids on British Naval Ships, with Tom Leahy recalling him as “very daring in that line” and that many rifles “were brought that way into Phil Shanahan’s shop in Foley Street.” Tom Daly may have assisted him. Tom Daly lived a quiet life, occasionally going for a pint in the Wharf Tavern, where in a throwback to his Frongoch days, local residents recall him pulling a pet mouse out of his pocket and dropping it into his pint to discourage it’s theft any time he left the bar counter. He died in 1941 and unlike his brother, whose funeral is still remembered as the largest ever seen in East Wall, Tom’s was modest, his role in the revolutionary period having faded by that time.

Since the original publication of this article we have received clarification on the death of Tom Daly which has now been been included.We would particularly like to thank Dario Reggazzi for information on his Great Grand-Uncle and the history of other members of the Daly Family.

For clarifications , corrections , further information or other comments please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Photo credits – The majority of images were sourced by Hugo McGuinness . ( Guardroom photo from material donated to East Wall History Group by the family of Irish Volunteer Richard Roe , Jacobs Garrison 1916 ).