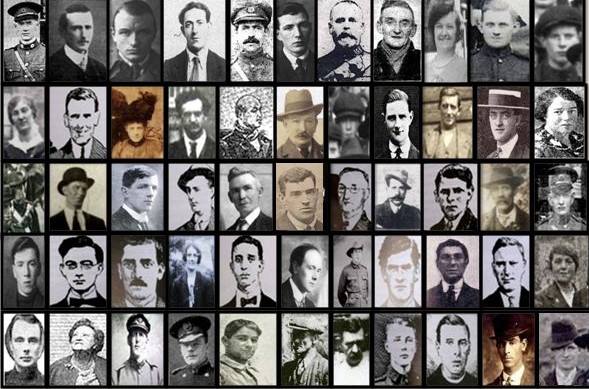

During the Easter Rising Centenary Year 2016 local history groups in the Docklands were busy ensuring that the anniversary was properly commemorated. The East Wall History Group and the North Docks Peoples Voice Project undertook extensive research, held and participated in a number of talks and walking tours. We also published a booklet and numerous articles on-line. On the exact dates of the Rising, each day we published articles recounting what happened a 100 years earlier. This is just a small selection of extracts from thismaterial, recalling some local heroes and events, just some stories from a week in the life of the North Docks at a turning point in Irish history.

The First casualties of the Rising

Anyone examining the 1916 Remembrance Wall in Glasnevin cemetery might be surprised to see the first casualties listed as occurring on 21st April, three days before the Rising began.

Charlie Monahan, Con Keating and Donal Sheehan were members of the Irish Volunteers, dispatched from Dublin to Kerry to assist in the landing of weapons for the Rising. On Good Friday evening their car plunged off the pier at Ballykissane and the men drowned. Belfast born Charlie Monahan had lived for some time at number 70 Seville Place, North Wall. He was a member of the St Laurence O’Tooles Club.

His companion, the Limerick born Donal Sheehan had joined the Irish Volunteers in London, returning to Ireland early in 1916. He was part of the Kimmage Garrison, made up largely of British born volunteers, based in the house of Joseph Plunkett at Larkfield, South Dublin.Also accompanying him was Con Keating. Originally from Kerry, he had also been resident at Larkfield, delivering ‘wireless’ training to volunteers here.

Charlie Monahan, Donal Sheehan and Con Keating were the first casualties of the Easter Rising, 1916.

Monday : From East Wall to Stephens Green

Easter Monday, 24th April 1916. By the afternoon an Irish Republic had been declared and the British Empire had been challenged. But for the people of East Wall, the first indication that this Day was going to be any different was earlier that morning, and occurred at the junction of Church Road and St Marys Road. Sometime shortly after 9 am a group of men gathered here and would soon set about the serious business of revolution.

James Fox had walked the short journey from his home at number 9 Hawthorn Terrace to the rendezvous. He would not have gone unnoticed, for what he was carrying was worthy of attention- a recently acquired Lee Enfield Rifle, which he would put to good use in the days to come. His weapon would certainly have been the envy of many of his fellow insurgents, the majority being equipped with the much inferior and obsolete ‘Howth Mausers’ or shotguns. One would later recall Fox’s activity during Easter Week and comment “prior to which, he on the 19th April, confiscated a Lee-enfield Rifle from a British Soldier at Ballybough, which he later used at Stephens Green”.

But before engaging in any combat, there was other work to be done. Arriving first, a glance down St Marys Road and he would have seen his fellow Irish Volunteers leave their houses and head up to the corner. Tim O’Neill from number 8 , Patrick Kavanagh from number 32 and Christy Byrne from number 45 joined Fox, as did Joseph Byrne from nearby Boland’s cottages (just off Church Road). All were members of E Company, 2nd Battalion, Irish Volunteers, who were based at Father Matthew Park, Fairview. They had received their mobilisation orders the previous evening, and had a very important early morning task to perform. (There may have been a sixth man present).

Under the command of Tim O’Neill, they quickly commandeered two wagons and horses. From where these were taken is unclear, but there were plenty of possible locations nearby. Cullen’s transport was based on East Road, and Nugents stables were located behind Seaview House. However, as Kipples Dairy (with its own yard and sheds) was situated at the junction where they had gathered it is likely to have been from there.

Having procured the two vehicles and horses they were soon on their way. One team made their way to a house in Drumcondra to gather rifles and home-made bombs, while another travelled to a variety of locations around Fairview and Ballybough collecting a quantity of rifles and ammunition. Their ultimate destination was Stephens Green, where they discharged their cargo to Commander Michal Mallin and Countess Markievicz. The East Wall five were posted to a section near the Shelbourne Hotel, where they took charge of the gate opposite Kildare Street.

Also posted in Stephens Green that fine spring day were two other East Wall men, the brothers Patrick and William Chaney from Northcourt Avenue. (Upper, Middle and Lower Northcourt–situated roughly where the Church now stands- were demolished and replaced by the Corporation Houses on Caledon Road and St Marys Road). The Chaney brothers were both aged in their early 30’s, and had been members of the Irish Citizen Army since it’s formation during the lockout of 1913. Unlike their Irish Volunteer neighbours, they had not set out from home that day. They had both been on duty at Liberty Hall since March, as part of the permanent ICA guard posted there, serving on a night shift after their days work a number of nights each week. As the date planned for the Rising drew near, they had also been engaged in the manufacturing of munitions which took place in the building. Setting off from Liberty Hall at noon that day, a contingent of the Irish Citizen Army had marched up Grafton Street, cleared visitors out of the Green and began to erect barricades and dig trenches.

The Stephens Green / College of Surgeons garrison was predominantly Citizen Army, with the five Irish Volunteers from East Wall something of an exception. Throughout the week they were amongst a group which tunnelled through the walls of adjacent buildings. All five would survive the week of intense combat here until the surrender on Saturday afternoon. They would soon be together at Frongoch Internment camp in Wales, where they would also be reunited with their neighbours and comrades who had served at other garrisons across the city. May Kavanagh, the 18 year old daughter of Patrick Kavanagh also served here as a member of Cumann naban , and in later years would recall “when she stood beside her father … and shot it out with British soldiers”.

British soldier dies on West Road:

The picture below shows the Railway signal box on West Road. It was here that at least two casualties occurred on Easter Monday 1916, in the opening hours of the Rising.

Monday afternoon, 24th April 1916. British troops under the command of Major Harold Fownes Sommerville had just engaged in a short but sharp shoot-out with the Irish Volunteers on the Wharf Road (now East Wall road). They had marched from the Bull Island Musketry School and were ordered to take control of the Docklands area. Under fire from volunteers on Leinster Avenue, they had dashed down the Wharf road and turned onto West Road. Some of them proceeded through the streets of East Wall to reach the Docks, while others scrambled up the rail wall to make their way along the tracks.

It was here that John Henry Sherwood of the 2/6th South Staffordshire Regiment was killed. The official verdict records that it was an accidental death, caused by a colleague while cleaning his rifle, however British Army reports we have seen confirm he was shot by members of the Machine Gun Corps. John Henry Sherwood was 19 and from Bilson, near Wolverhampton. Over the next few days he would become the most reported casualty of the Rising in the English Newspapers, reported as being shot by one of his own.

Also shot at this location was Paddy Whelan who operated the signal. He had stepped out to see what the commotion was in order to send a report up the line to Amien Street Station. A bullet hit him in the cheek, though it would not prove fatal. British troops would occupy the signal box and patrol the railway line for the remainder of the Rising.

Nearby houses, such as those on Moy Elta Road and West Road were peppered with bullets. This was only day one of what was going to be a tense and dangerous week for the local residents.

Tuesday: Two North Dock casualties at St Stephens Green

As dawn was breaking on Tuesday morning 25th April (the second day of the Irish Republic) the calm of the day was broken by the chatter of machine gun fire, as British bullets poured into the Rebel positions from the Shelbourne Hotel. James Corcoran from Seville Place was killed in the first burst, hit in the back of the neck. His body would lie where he fell until the following Sunday. Under intense machine gun and rifle fire from the overlooking buildings, the entire body of Rebels was withdrawn to the Royal College of Surgeons. Later that day another North Dock resident would fall victim to machine gun fire, being struck by twelve bullets while on the roof of the college. Despite his horrific injuries, Michael O’Doherty from Mayor Street would survive, only to die as a result of his wounds in 1919. Christine Caffrey, from Abercorn Road, was amongst the group that first secured the college building, having waved her revolver to drive away a hostile crowd that gathered to harass them. She would spent much of the week engaged in the dangerous task of travelling back and forward to the GPO headquarters with dispatches. On one occasion, when approached by a British soldier she started to eat the message and when challenged offered him a bag of peppermint sweets, and got waved on her way.

Wednesday: Denis Kelly – a civilian casualty on the Docks:

On Wednesday the 26th April 1916, a North Dock resident Denis Kelly died as a result of gunshot wounds he had received the previous evening. His wounding had taken place on the second day of the Easter Rising, when the docks area was already heavily occupied by British troops, who were being subjected to sniper fire throughout the vicinity.

Denis Kelly, was a goods checker at the London North Western Railway (LNWR) , North Wall. Kelly was born near Rathangan in County Kildare. Moving to Dublin he secured a good position with the Great Southern Railway at Kingsbridge (Heuston) Station about 1896. In December of 1909 he switched his employment to LNWR, where he worked as a checker at their North Wall Railway Station.

The Kelly’s lived at No. 13 North Dock Street. It’s unclear what took Denis Kelly out on the streets on the evening of Tuesday 25th April 1916. Some in the family believe he went out to seek food for his children, which suggests he may have been shot near the shop on Castleforbes Road. Another suggestion is that he was in the vicinity of New Wapping Street when a gun battle broke out and rushing for cover in a nearby shed he was hit by a stray bullet. Whatever the exact circumstances, Denis Kelly was wounded in the shoulder and lost a lot of blood before the ambulance arrived at 9.22pm. He died the following day from a combination of shock and haemorrhaging. Denis Kelly was buried in a mass grave of civilian casualties at Glasnevin Cemetery. His wife was in care, and he had three children. Following his death the children were brought up by relatives in County Kildare.

Thursday 27th April: A TALE OF TWO DEATHS

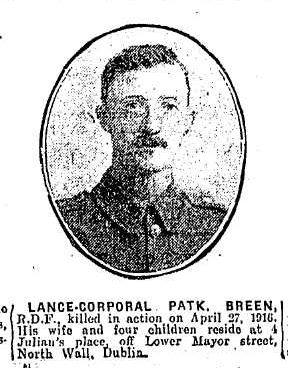

On the 27th April 1916 Lance Corporal Patrick Breen of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers was one of the 338 Irish Men who died in a German Poison Gas attack at Halluch in France. With an address at Julian Place (off Mayor Street) North Wall, Patrick Breen was aged 27 at the time of his death, and left behind a wife and four children.

One survivor of the horrific events recalled: “…the Dublin Fusiliers had been caught unawares and their casualties were very heavy. When it was over, I had the sad job of collecting and burying the dead. They were in all sorts of tragic attitudes, some of them holding hands like children in the dark. They were nearly all gassed and I buried about 60 of them in an enormous shell hole.”

The death of Breen occurred during the week of the Easter Rising. In response to the events in Dublin, German soldiers had placed signs in the trenches stating “Irishmen … English guns are firing at your wives and children”.

On the day that Patrick Breen died , if his wife and children were at home in North Wall they were indeed in extreme Danger from ‘English Guns’ , as their near neighbour Janie Costello from 113 Seville Place would discover when a moment of curiosity caused her death. As soldiers were making house to house searches her curiosity got the better of her and she looked out the window. A soldier taking cover in a doorway spotted the movement and opened fire, hitting Janie through the lungs. “I’m shot! Oh! Katie, I’m done!” were her last words before she fell lifeless to the floor.

The shots were barely audible to her flatmate Katie Lewis, who was beside her as she died. Two bullets had passed through Costello’s lungs, one embedding in the door jamb of the room, the other in the wall inches above a neighbour Mrs. Hanlon who was visiting at the time. The situation could have been far more tragic, with the possibility of more fatalities.

Ironically, two of Jane Costello’s brothers were serving in France with the British Army at the time of her death.

Neighbours shot as Troops swamp area

Jane Costello’s death was just one fatality in what would be a grim day in the Area. Another young woman was shot dead and amongst the wounded were two boys, one who would later die from his injuries.

Julia Crawford was aged 20, married just one year, when she was shot by British Troops at Irvine Crescent, East Wall. Despite the efforts of a British Major to save her live she died at the scene. The same afternoon two young boys were shot – 12 year old Edward Ryan and 8 year old Walter Scott. Ryan was hit in the leg and would recover, while Walter (who was hit in the head) would linger horrifically before dying in July. Walter and his family also lived at Irvine Crescent. It was a harsh year for the Scott family. His father had died after an accident in the Port in February, leaving Anna Scott with a number of children in her care.

Note: Irvine Crescent is now incorporated into Church Road, and is located opposite Johnny Cullen’s Hill.

A week under fire …and fired:

Arthur Hannon from 12 Saint Laurence Street was just 16 years old in Easter Week 1916. He was involved locally at the start of the insurrection, would serve in the GPO Garrison and would be present for the retreat to Moore Street and the Surrender. Though his brother James was a member of the Irish Volunteers and would serve at Jacobs, Arthur was not a member of any of the military bodies which set out to challenge the British Empire that Easter Monday morning .This would not remain the situation for long. Arthur first joined up with the rebels at Annesley Bridge and being youthful and in possession of a bicycle he was dispatched to get details on British Troop movements in the Docks. Recognised at Oriel Street as a rebel, when Biddy Latimer shouted out – “He’s a bloody Sinn Feiner” he quickly came under fire from the troops he had been chatting to, and gathering information from, but luckily escaped uninjured.

His career as an ‘intelligence gatherer’ at an end, he returned to the barricades at Annesley Bridge. He was posted to the Dublin & Wicklow Manure Works (where Ballybough house now stands). Here he was given another choice job- tasked with looking after a group of Volunteers from outside of the city who had no idea where they were. According to Arthur – “They were all from other parts of Ireland. I was the only Jackeen in the group, without me they would never have reached the post office”. Having guided them into the GPO Headquarters on Tuesday, he served from here through the remainder of the Week through to the surrender on Moore Street on Saturday. He carried messages back to Fairview and also the Four Courts, and was dispatched to help prevent the looting in the vicinity.

On armed duty within the GPO, he would decades later recall a significant incident – “The most clear and vivid memory I have of the week was my idol James Connolly leaving the GPO and his being carried back……I opened the door when Jim Connolly took six or seven men to attack the telegraph building and opened it again when he was carried in wounded”.

Reflecting on events surrounding the surrender he would remember that: “I was in some fish shop on Moore Street with the men I had been with since Monday. We stuck together in the Post Office and in the hectic dash across Henry Street and into Moore Lane. We really erected the barricades across Moore Lane .These men were all from Longford and Roscommon”. Afterwards he “spent the night bivouac on the lawn of the rotunda hospital when we surrendered. I spent the next week in Kilmainham barracks. I still stuck to my original group from Fairview”.

Due largely to his age Arthur was soon released. But it wasn’t all good news! During his activity he had been spotted by his boss, a Mr Templeton “who was in the crowd and spoke to me”, and upon his release he was informed that the firm of Hugh Moore and Alexander no longer required his service -“They didn’t want my kind”. Having lost his job as an office boy, he then went to sea to earn a living.

While his military career may have been short lived, he was still prepared to strike a blow for Ireland when the opportunity arose, as this escapade reveals – “I was in Dublin again in 1917 when on a dare (from Daniel McCarthy, boy scout leader) I climbed the ruins of the GPO and burned the English flag and placed the tri-colour of the Republic in it’s place”.

This is just a small selection of stories collected and shared by the East Wall History Group and the North Docks Peoples Voice Project.

The book “All the Brilliance of the Day” by Hugo McGuinness will be published later this year, a detailed account of the events of the Easter Rising in the North Docks.

If you have any family stories, photographs or other memorabilia please to share please contact us at

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

northdockpeople@gmail.com

Details from sketch by Charlie Saurin , Irish Volunteer , a participant in the ‘Battle at Annesley Bridge’ . Image shows combat at building site between Leinster Avenue and East Wall Road (where houses now stand).

Image: Bureau of Military History