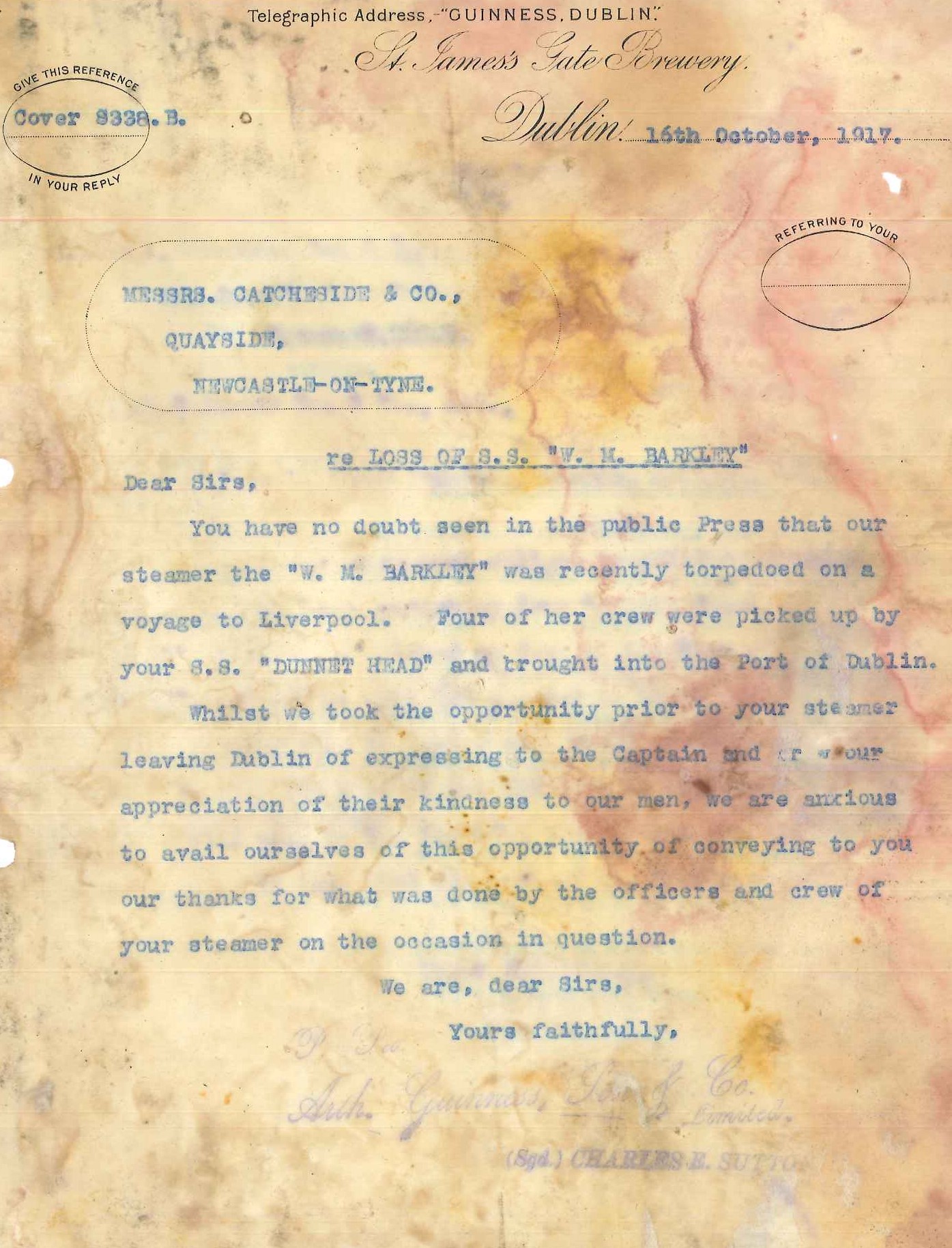

Guinness archivist Eibhlin Roche , with model of SS WM Barkley

On 12th October 1917, the steam ship WM Barkley having set out from Dublin Port just hours earlier was torpedoed just off the Kish lighthouse. Five of the 13 crew members on board were killed, and the others were lucky to survive. Among those to lose their lives was Thomas Murphy of Sheriff Street, who left behind a sick wife and two children. The WM Barkley has an interesting history, being the first vessel of the famous Guinness fleet, and also because there is a vivid first-hand account of the attack, which gives an amazing insight to the terrifying experiences endured by those onboard and so many other seamen. This is the story of the sinking of the Barkley and of its crew- those who lost their lives and those who survived:

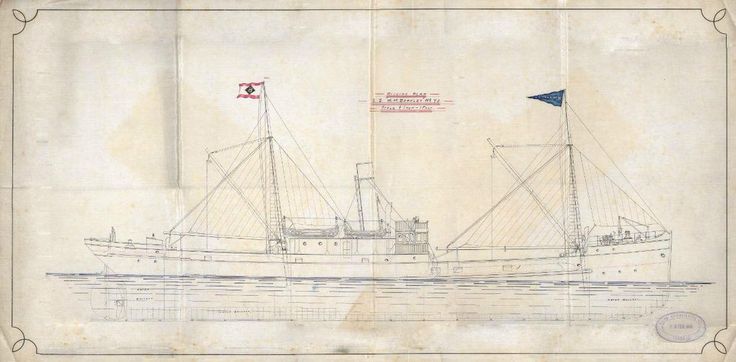

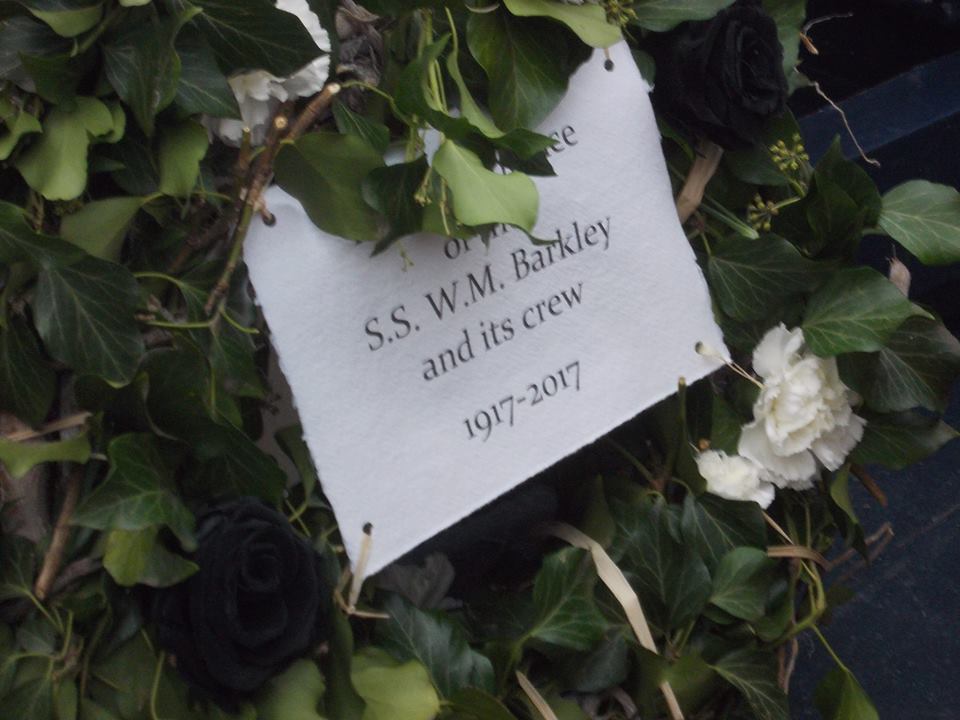

Guinness is the most iconic of all Irish brand names. Manufacturing stout since 1759, in the early years of the 20th century the company was engaged in a busy cross channel trade, contracting a variety of carriers using the Dublin to Manchester and Liverpool routes. During the great Lockout of 1913 the transportation of Guinness was severely impacted. Though the company was not directly involved in the fierce industrial conflict that gripped the city, the disruption of commercial shipping due to sympathetic strike action affected their cargoes. Not prepared to have their business affected by events outside of their control, the company decided to invest in their own ships, and the legendary Guinness fleet was born. Before the year was out the first vessel was purchased, the WM Barkley. Built in 1898, the ship was only in service for Guinness a short time when world events would change her destiny drastically. In 1914 Great Britain and Germany would go to war, and she was commandeered by the British Admiralty. A number of perilous voyages were carried out in this new role, including transporting road building material to France, carrying timber to Britain and iron from Glasgow to Dunkirk. However, the vessel was eventually deemed not suitable for this war work and was returned to the company. Despite now being engaged only in commercial voyages, a German declaration in 1915 that the Irish Sea was “within the seat of war” and “that all enemy vessels found in these waters after 18 February would be destroyed” would seal her fate. In 1917 this policy was intensified and the Irish channel became particularly treacherous.

Coastal waters declared as ‘within the seat of war’

On Friday 12th October 1917 she set out from Dublin Port with a cargo of Guinness destined for Liverpool. She would never complete the journey. Sailings from the Port had been suspended due to the increase of U-Boat attacks, and had only been lifted that very day. Tragically, the restrictions would be re-imposed almost immediately, but for this vessel and her crew this renewed caution would prove justified but too late. Having departed the city at 5pm it was at 7.45pm when her encounter with UC-75 would see the vessel struck by a torpedo and almost immediately break in half.

This vivid account of the attack was written by survivor Thomas McGlue (and published by Guinness in their ‘HARP’ magazine in 1964) -

“I was in the galley, aft of the bridge. I was just reaching out to take a kettle off the fire to make a cup of tea for the officers. When we got the poke, the kettle capsized and shot the boiling water up my arm to the elbow. The galley was filled with steam and I said a few hard words, but apart from that there wasn’t much noise – not a murmur, in fact.

The port side of the ship was locked to keep it dark, so I went through the engine room and out on the starboard deck. There was a lifeboat hanging there, hanging by one end to the forward fall. The Barkley was doing her best to go down, but the barrels were fighting their way up through the hatches and that kept us afloat a bit longer – in fact, it’s the reason any of us got out of her.

The master gave three blasts on the siren and then I didn’t see him anymore. I climbed into the boat and a mate gave me a knife to cut the fall and the painter. The boat dropped clear and dipped under a bit and we had to do some fast bailing. The other fellow was all for us getting away while we could, but I said No there’s more than two of us here and they’ll want to come along. Then the gunner came up – we had one gun on the after deck but he wasn’t at it when we got the poke; as a matter of fact, he was in the galley with me, waiting for some hot water to do his washing with. I don’t know where he’d got in between.

The gunwale of the lifeboat had been ripped when we were hit and the gunner gashed his leg on it, getting in. Then another A.B. [Able-bodied seaman] jumped in and that was four of us. We rowed away from the Barkley so as not to get dragged under, and we saw the U-boat lying astern. I thought she was a collier, she was so big. There were seven Germans in the conning tower, all looking down at us through binoculars.

We hailed the captain and asked him to pick us up. He called us alongside and then asked us the name of our boat, the cargo she was carrying, who the owners were, where she was registered, and where she was bound to. He spoke better English than we did. We answered his questions and then asked if we could go. He told us to wait a minute while he went below and checked the name on the register. Then he came up again and said: “I can’t find her.” He went back three times altogether. Then he came back and said: “All right we’ve found her and ticked her off.” We said can we go, but there were two colliers going into Dublin and he told us to wait until they were to windward and couldn’t hear our shouts. Then he pointed out the shore lights and told us to steer for them.

The submarine slipped away and we were left alone, with hogsheads of stout bobbing all around us. The Barkley had broken and gone down very quietly. We tried to row for the Kish light vessel but it might have been America for all the way we made. We got tired and my scalded hand was hurting. We put out the sea anchor and sat there shouting all night.

(Courtesy: Guinness Archive , Diageo Ireland)

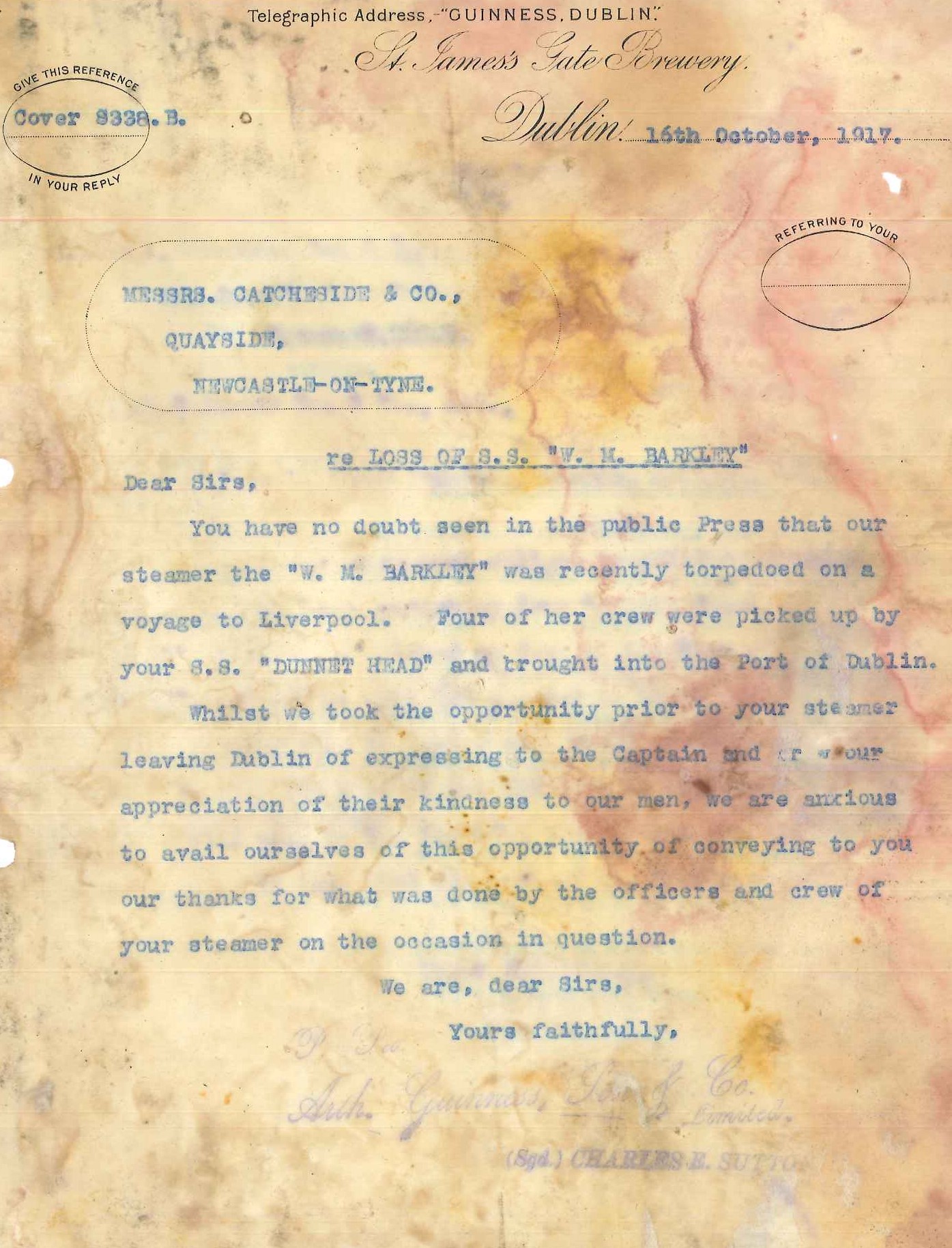

At last, we saw a black shape coming up. She was the Donnet Head, a collier bound for Dublin. We got into Dublin about 5 AM and an official put us in the Custom House at the point of the Wall, where there was a big fire. That was welcome because we were wet through and through and I’d spent the night in my shirtsleeves. But we weren’t very pleased to be kept there three hours. Then a man came in and asked “Are you aliens?” Yes, we’re aliens from Dublin. He seemed to lose interest then, so we walked out and got back into the lifeboat and rowed it up to Custom House quay. The Guinness superintendent produced a bottle of brandy and some dry clothes and sent the gunner off to hospital to have his leg seen to. The rest of us went over to the North Star for breakfast. And later, after I’d had my arm dressed – the doctor said the salt water had done it good – the superintendent gave me a drayman’s coat to wear and put me in a cab.

I was glad to get back to Baldoyle, because I’d left my wife sick and was afraid she’d hear about the torpedoing before I could get home.”

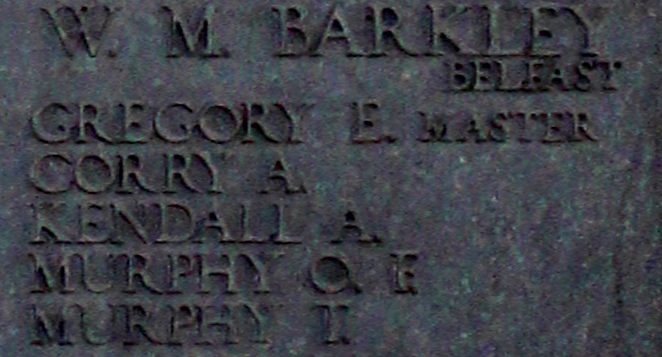

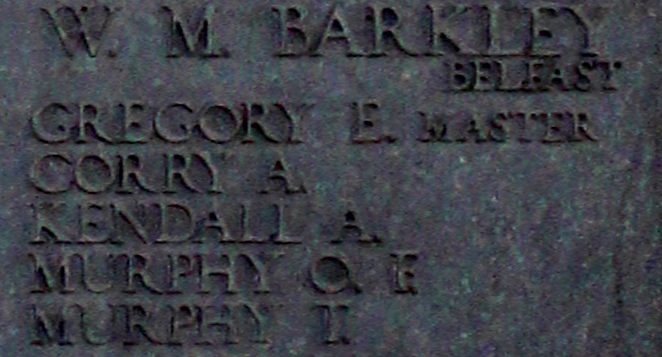

As remembered on the Merchant Seamen memorial , Tower Hill , London.

Those who died during this attack were

1. CORRY, ALEXANDER (age 48), First Engineer from 3, Victoria Villas, Dublin. (Born at Belfast)

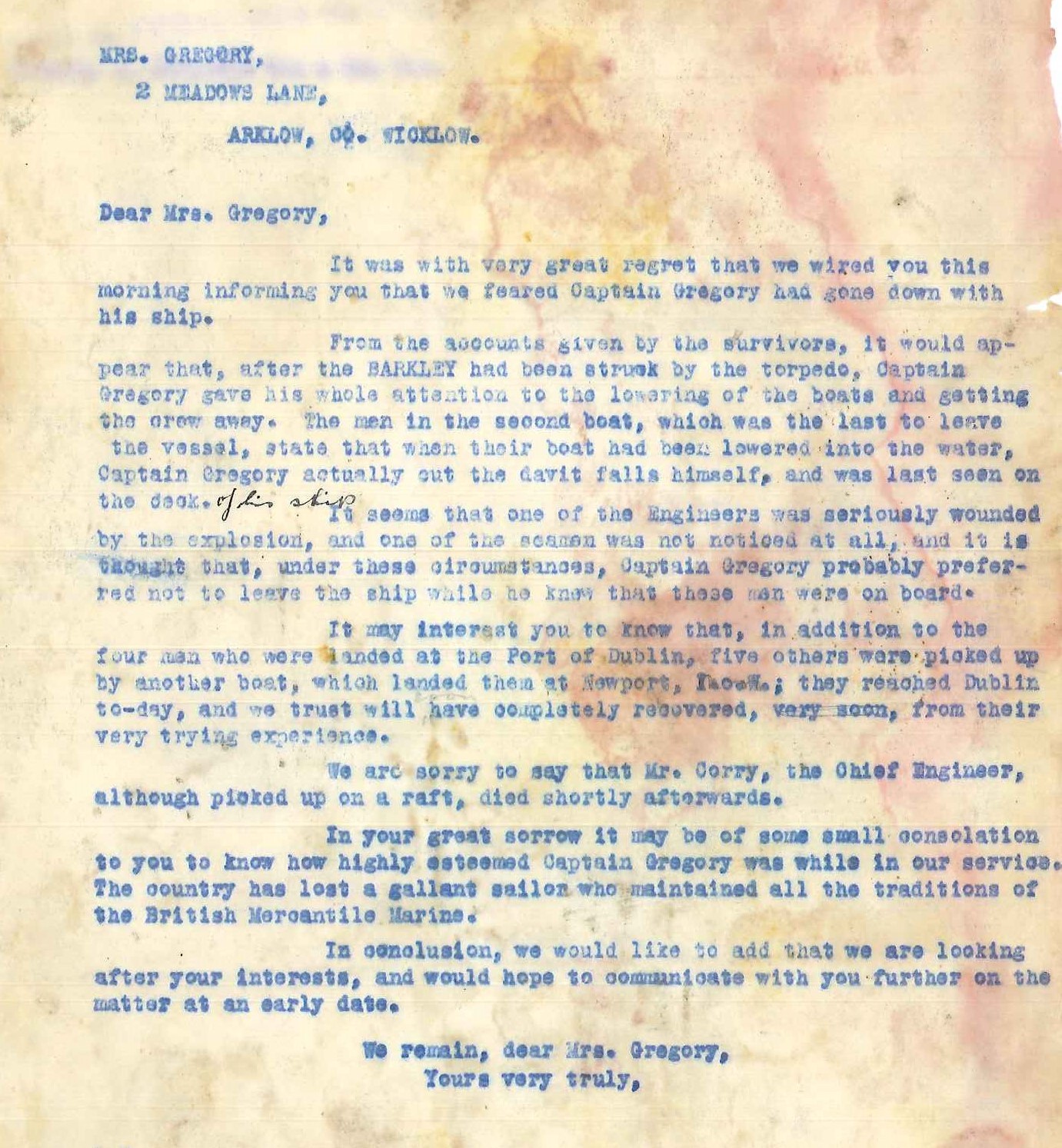

2. GREGORY, EDWARD (age 46), Master from 2 Meadows Lane, Arklow, Co. Wicklow, (Born at Arklow)

3. KENDALL, ARTHUR (age 40), Able Seaman from 3 Meany Place, Dalkey, Co. Dublin. (Born at Falmouth)

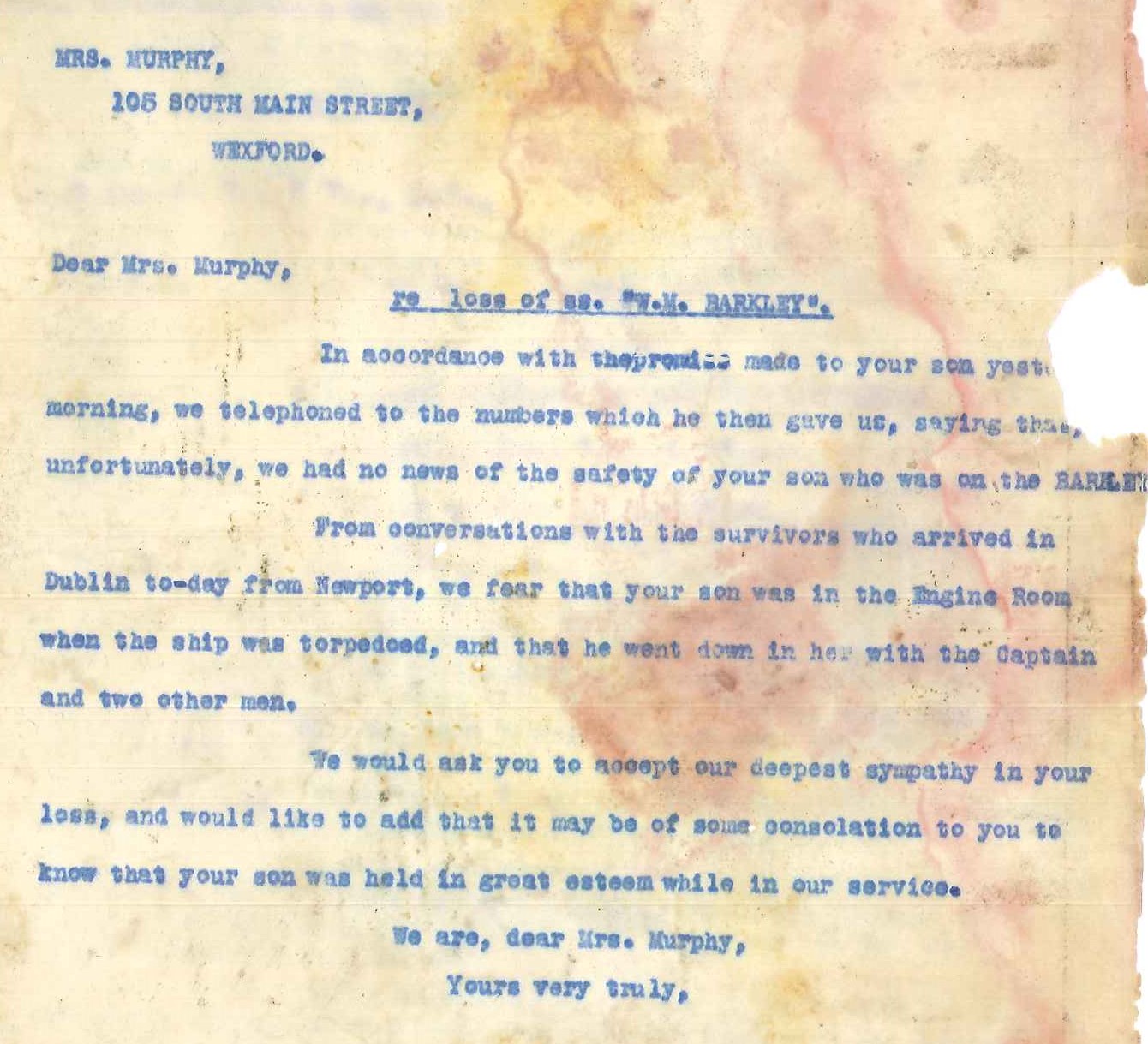

4. MURPHY, OWEN FRANCIS (age 28), Second Engineer from 105 South Main St., Wexford. (Born at Wexford)

5. MURPHY, THOMAS (age 29), Ships Fireman from 36, Lower Sheriff St., Dublin. (Born in Dublin).

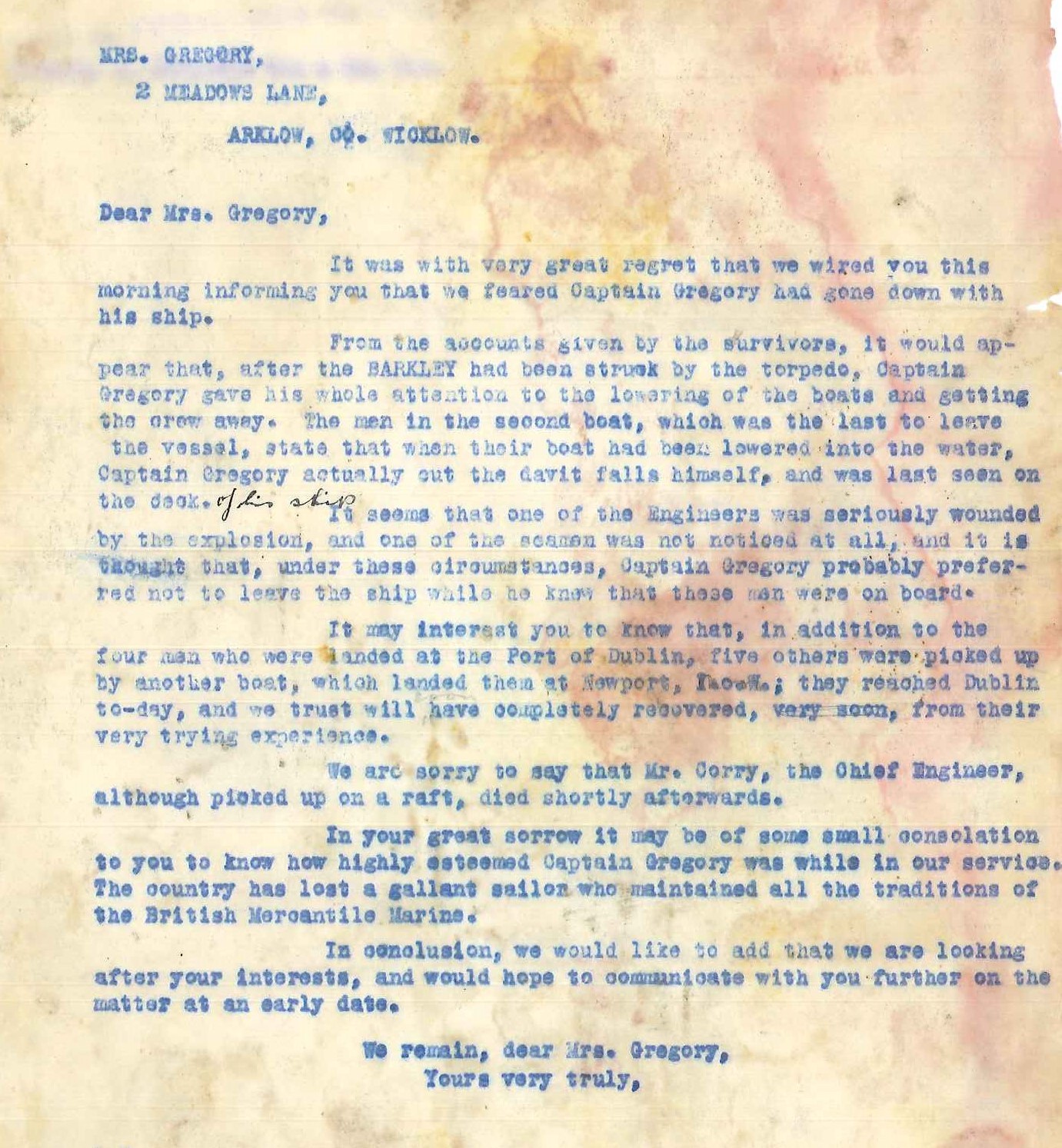

These two letters are heartbreaking, sent by Guinness to the next of kin of Captain Gregory (of Arklow) and Owen Francis Murphy (of Wexford).

(Courtesy: Guinness Archive , Diageo Ireland)

(Courtesy: Guinness Archive , Diageo Ireland)

The youngest man was unmarried, the others each left behind a wife, and a total of seven children, and Arthur Kendalls wife was pregnant. A report by the Guinness Company on the loss noted that the wife of Thomas Murphy of 36 Sheriff Street was “currently dying in hospital” and “who leaves in addition two children”. According to the company – “Arrangements have been made for dealing suitably with all cases”.

Thomas Murphy lived with his wife Mary (nee O’Rourke) at 36 Lower Sheriff Street. According to the 1911 census, at that time he was living at number 4 Leland Place with his parents Anne and John (a gas labourer), who had come from Meath and Kilkenny respectively. Thomas was already employed as a ships fireman and two of his sisters were also employed -Catherine (a factory girl), Mary Ellen (a box maker), with the remaining siblings still at school – Martin, John, Lusia and Nicholas. His older brother, Patrick (a labourer) had moved on by this time. As was unfortunately common place in Dublin, three other siblings had died. By the time of his death onboard the Barkley in 1917 his mother had already died.

The company were of course also interested in protecting their commercial operation. In light of the loss of the WM Barkley they had written to the Transport Department of the Admirality requesting the return of another of their steamers that had been requisitioned for the war effort “to enable us to cope with the present trade conditions”.

In a strange sequel to this tragedy, reports of casks of Guinness being discovered floating or being washed ashore continued in the following weeks.

The SS Hare, (best remembered as ‘Larkins food ship’) though never part of the Guinness fleet had regularly transported the black stuff across the Irish Sea. The Hare was torpedoed just over two months later, on the 14th December, very close to where the Barkley was targeted. 11 of it’s crew would perish. Though it was not carrying any Guinness produce at the time, in what was a very generous gesture, the company was prepared to offer financial assistance to the families of those lost when the SS Hare was destroyed. This was deemed unnecessary, as a public fund raising committee was incredibly successful. Guinness as a company contributed to this fund, as did the coopers seperately. The fund was administered by, among others Lord Mayor Alfie Byrne and Canon Brady of St Laurence O’Tooles parish.

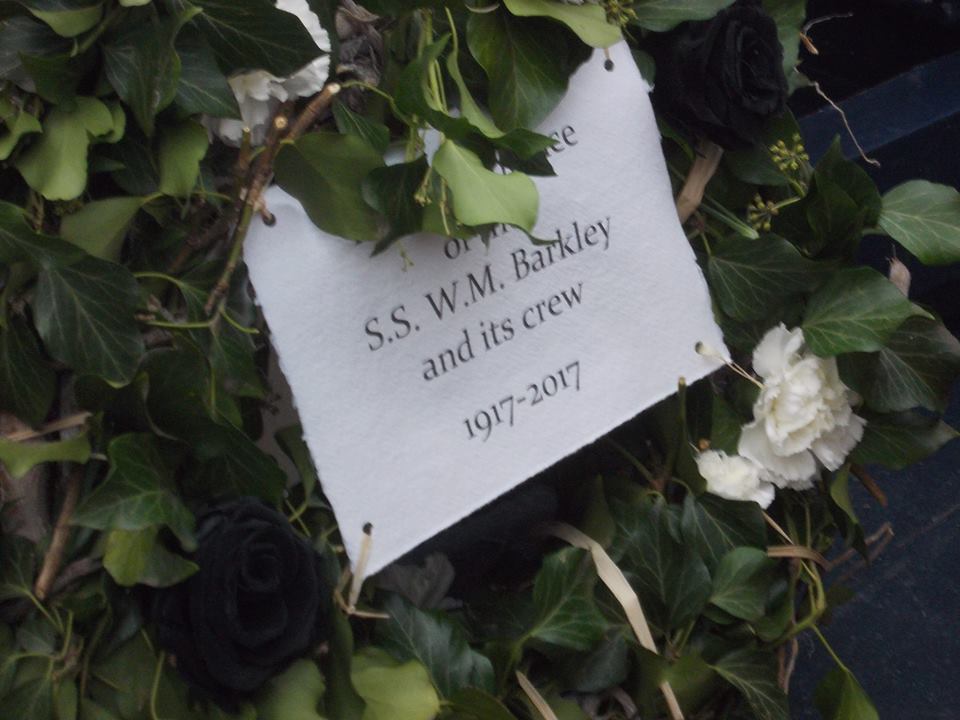

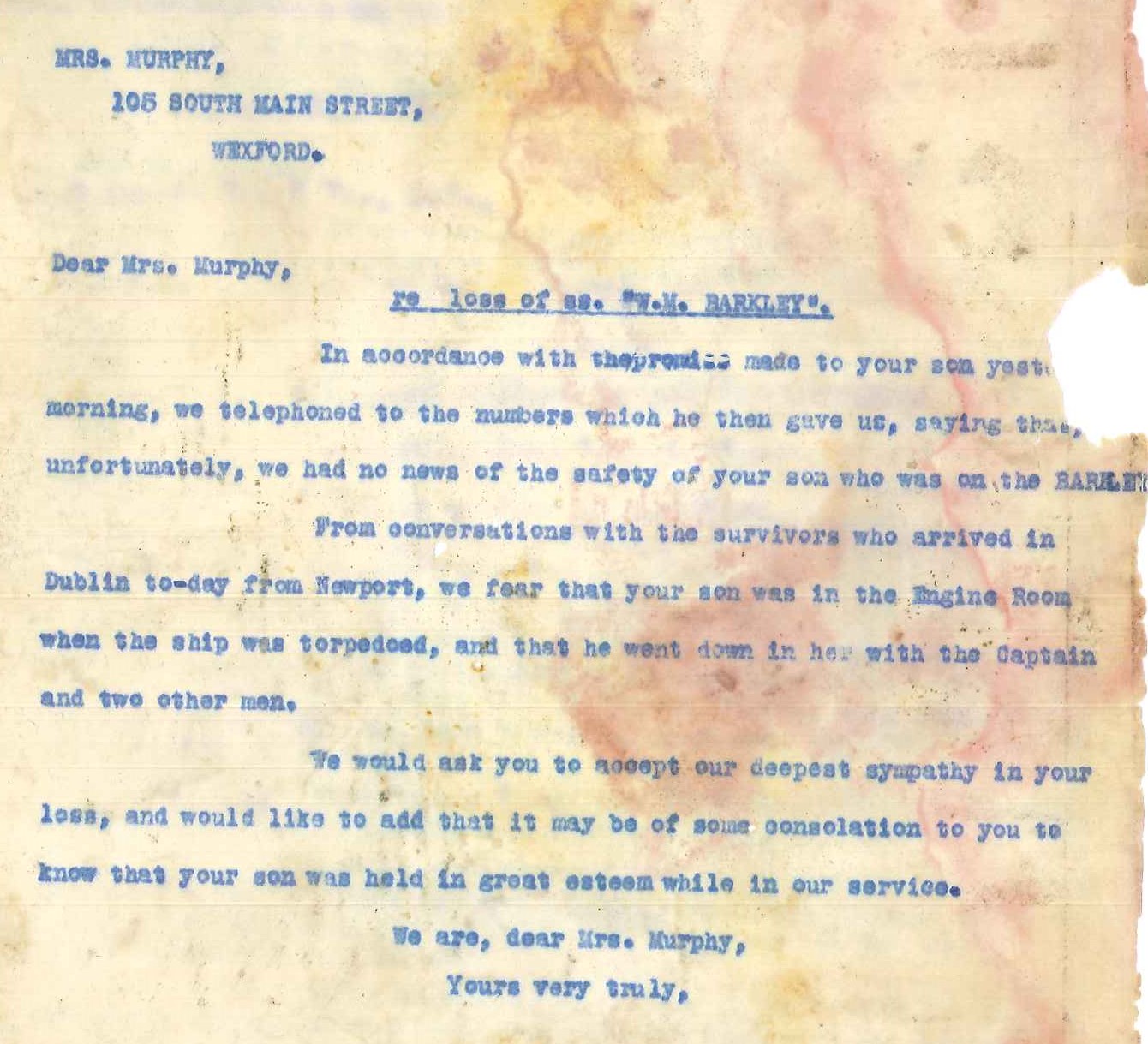

On the 30th September 2017 a commemoration event took place to remember those lost onboard Dublin Port ships due to U-boat attacks in 1917. Family members of the crew of the SS Adela and SS Hare set out into Dublin Bay aboard the St Brigid (operated by Dublin Bay Cruises) to place wreaths in the waters their families had sailed a century before. The Guinness ship was also remembered, with Fergus Brady of the Guinness Archive representing the company.

(Courtesy: Guinness Archive / Diageo Ireland)

A painting and model of the WM Barkley can be seen at the Guinness Storehouse.

For further information , corrections or clarifications please contact : adelahare1917@gmail.com

With thanks to Fergus Brady .

(Images courtesy Guinness Archive / Diageo Ireland , used with permission)