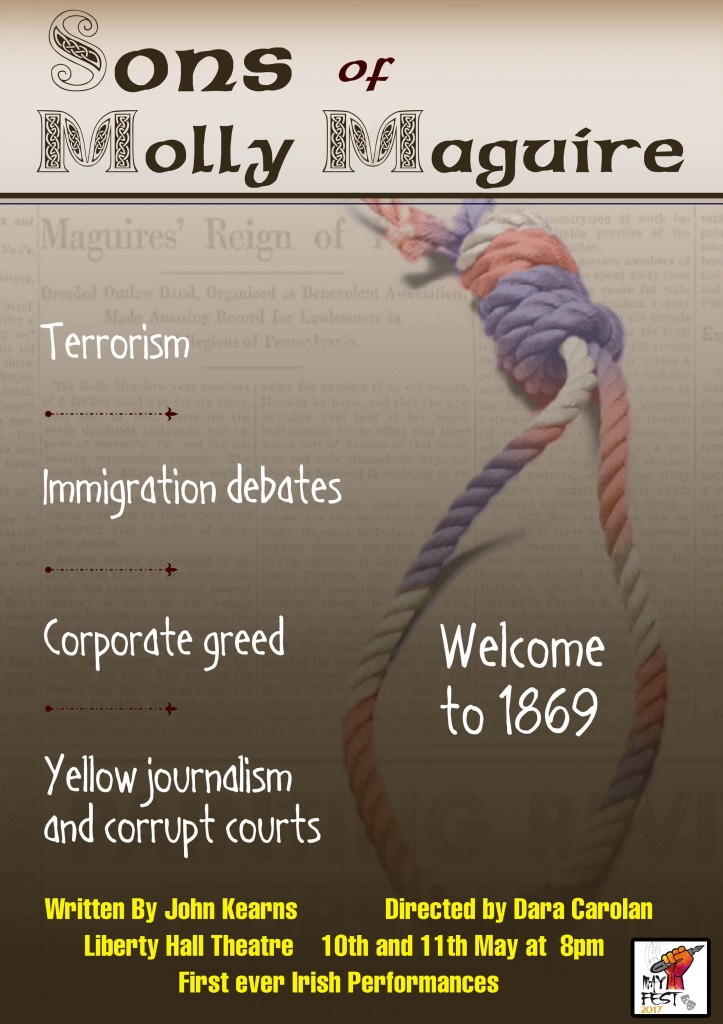

It is remembered as “The Day of the Rope”, when, on the 21st June 1877; ten Irishmen were hanged in Pennsylvania. By the end of 1879 a total of twenty Irish Immigrants had been executed for their alleged role in the deaths of mine owners, foremen and police in the Pennsylvania coal fields. And last year ,for the very first time, their story was told on an Irish stage. As part of MayFest 2017 at Dublin’s Liberty Hall Theatre, “Sons of Molly Maguire” by John Kearns received its Irish premiere on 10th and 11th May.

John Kearns is the Treasurer and Salon Producer for Irish American Writers and Artists (IAW&A). He is the author of the short-story collection, Dreams and Dull Realities and the novel, “The World”, along with plays including “In the Wilderness” and In a Bucket of Blood. “Sons of Molly Maguire” has previously been performed at the Midtown International Theatre Festival in New York, and this is the first production outside of the United States.

While telling a fictionalised version of the Molly Maguires’ story, the play blends realism with pageant, mime and flights of poetry. It also questions the construction of history itself, since the illiterate alleged Mollies left no records preserving their point of view. In this short feature, Joe Mooney of the East Wall History Group explains the historical background to their story.

“Thousands are sailing…”

In the mid to late 1800s thousands of Irish immigrants arrived in America. They had left their homeland to escape famine, land seizures, poverty, religious and political oppression. For many, the dream of a new life in the land of the free was soon to end as they found themselves facing old oppressions in a new guise. Those who settled in the mine fields of Pennsylvania had carried more than dreams across the Atlantic; they also brought the traditions and tactics that had flourished at home. A merging of agrarian revolt and developing proletarian organisation gave birth to the militancy associated with the Molly Maguires.

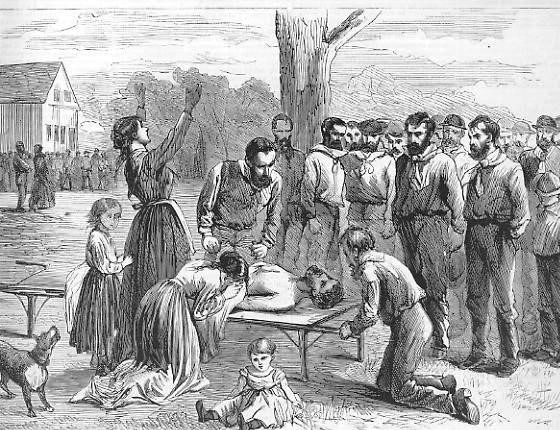

The Pennsylvania coal-fields were booming as Irish Immigrants arrived. Conditions for all workers were appalling, and competition for jobs was fierce, with the companies using immigrant labour to force down wages. The mining bosses often owned the housing the workers lived in and food and other essentials were sourced from the overpriced company store. Children as young as seven were employed. Long hours, a rush to meet quotas, and unsafe conditions led to fatalities and disasters. In Schuylkill County, home to thousands of the Irish, 566 deaths and over a thousand and a half serious injuries were recorded in a seven year period. In one fire 110 miners died as there was no secondary exit available to them. Safety laws did exist, but as the coal companies themselves were responsible for enforcement these were ignored.

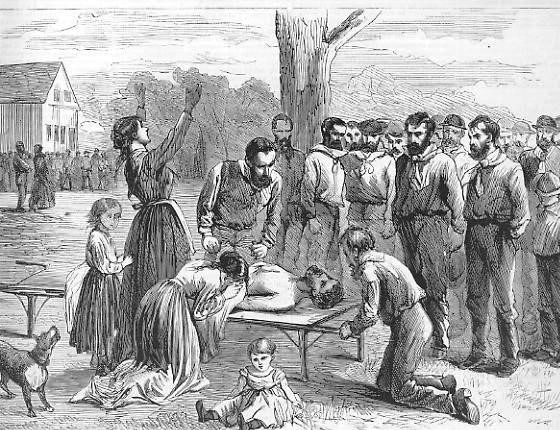

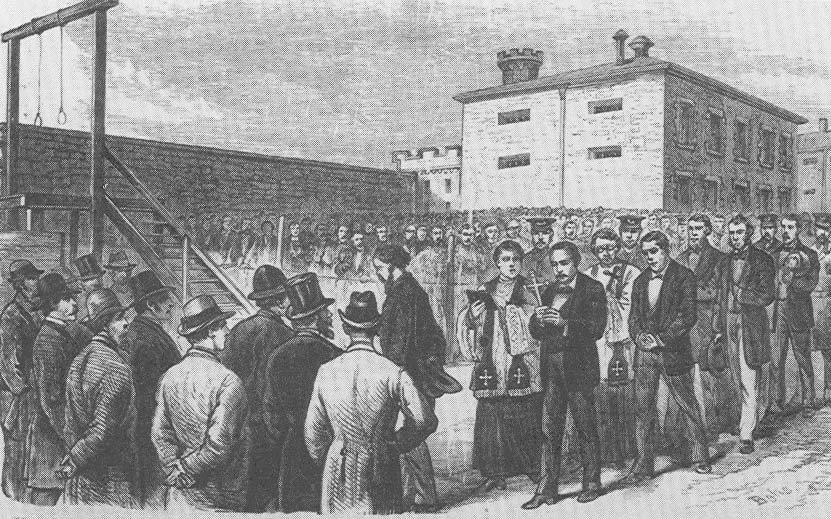

“Friends claim their dead” . Newspaper illustration after death of 110 men in fire disaster

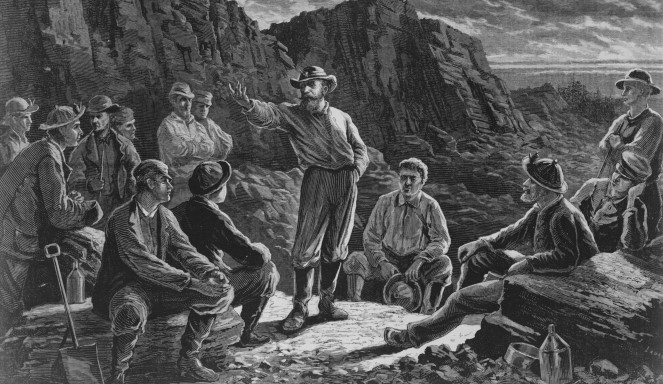

Organise!

In 1868 a miners union, the Workingmens Benevolent Association (WBA) was established to fight for improved pay and conditions. Its Irish born founder John Siney had previous trade union experience in Lancashire. Most of the Irish miners became members of the WBA and were well represented in its leadership.

The WBA was not the only group they joined. Aside from Labour concerns, the Irish again faced racism and religious discrimination. Being rural, Catholic and Gaelic speaking they stood out amongst other immigrant communities. Many had gravitated towards the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), to enjoy the associated fraternal benefits.

And then, of course, there were the Molly Maguires.The Irish in Pennsylvania had come mainly from north western counties, particularly Donegal, associated with agrarian secret societies and land war violence. The tactics of groups such as the Molly Maguires, Ribbonmen and Whiteboys —intimidation, threats, assaults and assassinations —that had targeted landlords, land agents and bailiffs at home were just as effective against mine owners, foremen and the police. New enemy, new battlefield, same response. The origin of the name is uncertain – it had been used previously in Eire, and legend says Molly Maguire was the victim of an early eviction who had sought retribution. The expression “Take that from a Son of Molly” was supposedly shouted before a killing in revenge attacks.

The Coal, Iron and Rail baron

Just as William Martin Murphy is synonymous with the 1913 Lockout in Dublin, one name stands out amongst the capitalists of Pennsylvania – Franklin B.Gowen. He was no friend of the workers, and was determined to smash their organisations – when locomotive engineers had asked for a pay rise he demanded that they leave the union or give up their jobs. During the great railway strike in 1877, he thought himself immune, and bragged that “the men have no organisation, and there is too much race jealousy existing among them to permit them to form one.” They did in fact strike, and ten unarmed people were shot dead by the state militia. He also had many political connections, and a private force, the ‘Coal and Iron Police.’

In 1874 he initiated the Anthracite Board of Trade, an employers’ federation, and instigated a strike by imposing a 20% pay cut. The ‘Long strike’, ended in defeat as workers were starved into submission. Jailings, vigilante attacks and murders took place at this time.

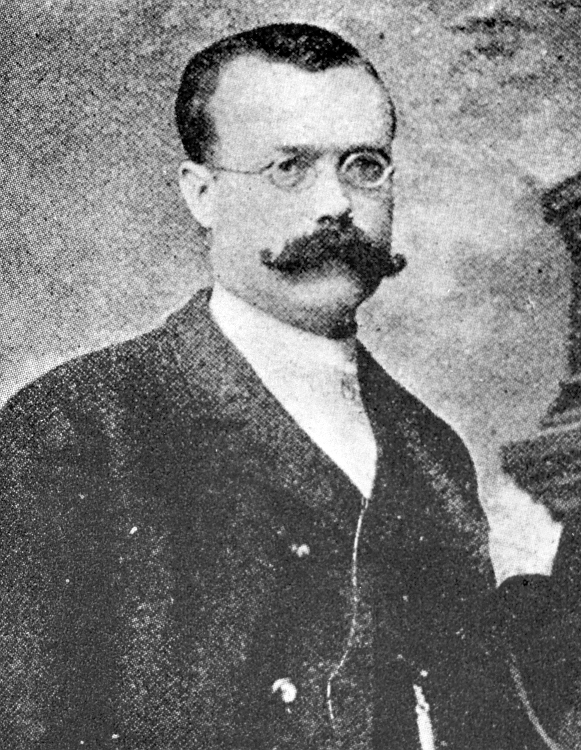

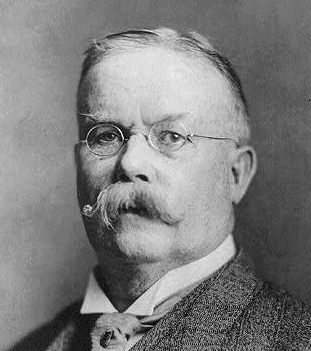

Franklin B. Gowen

“…print the legend”

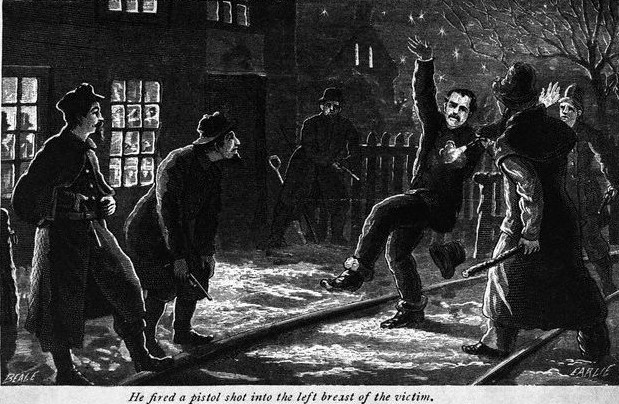

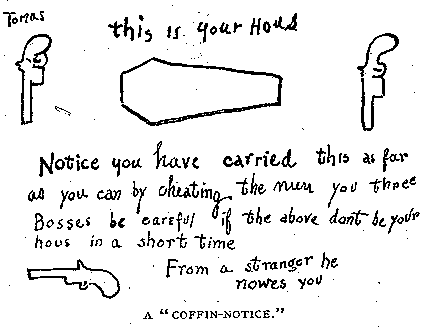

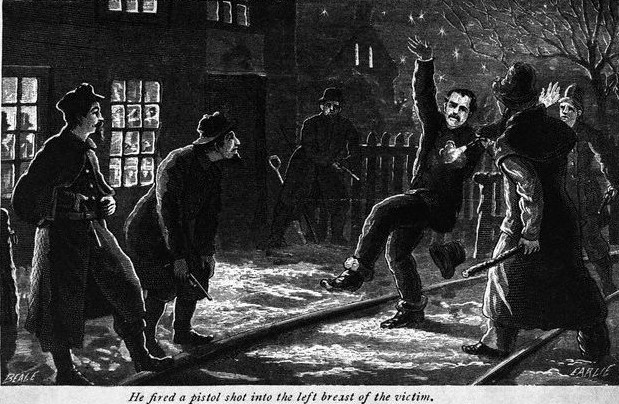

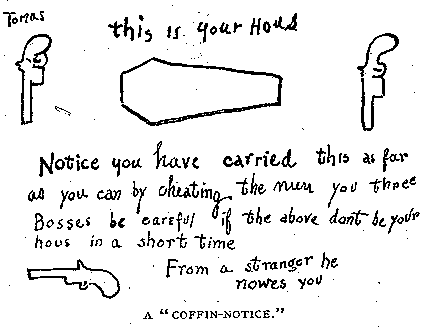

Court cases attributed 16 deaths to the Molly Maguires. The first was a mine foreman beaten to death in 1862, the last a foreman, shot dead in 1895. Other acts associated with the ‘Mollies’ were sabotage, arson, assaults and intimidation. ‘Coffin notices’ – threats with pictures of coffins (or pistols) were posted against enemies, some signed M.M. Many of the actions were carried out by men with painted faces and wearing long dresses, not only as disguise but a theatrical flourish in imitation of their Irish forefathers. This suggests cultural awareness as well as economic necessity in their actions.

Gowen was determined to smash all threats to his empire, and targeted with equal venom the legal WBA and the outlaw Mollie Maguires. He unleashed a wave of violence using his private police force and vigilantes, and employed the notorious Pinkerton Detective agency to infiltrate the Irish workers. Even amongst his own class some concerns arose about his approach, buthe was a canny propagandist, and he used the newspapers to justify his actions. Soon the press was full of terrifying tales of the savagery in the coalfields, and the WBA, the AOH and the ‘Mollies’ were branded as all part of the same foul Irish conspiracy. These were often accompanied by illustrations depicting the miners as ignorant and often ape-like, familiar racist propaganda. Anti-Catholic prejudice was also invoked, even though the Church of Rome threatened excommunication for belonging to a secret society.

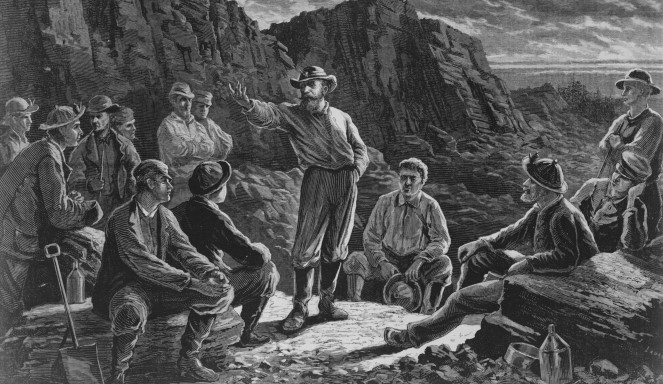

A meeting of the Molly Maguires

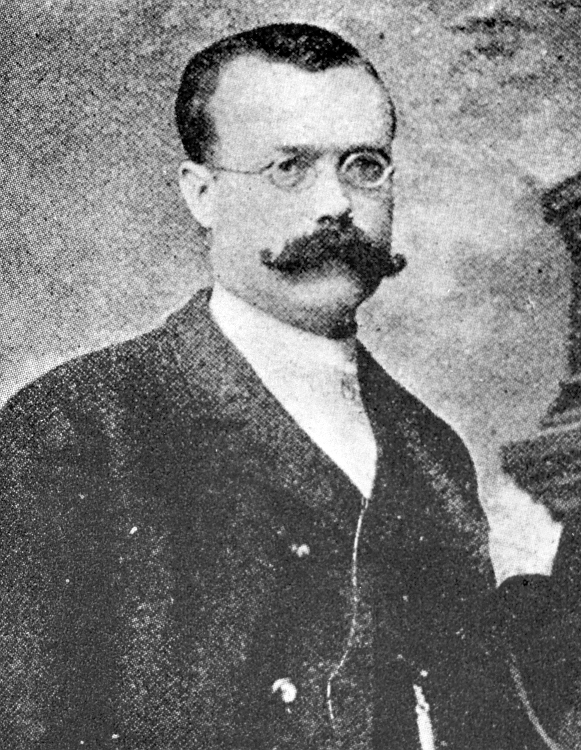

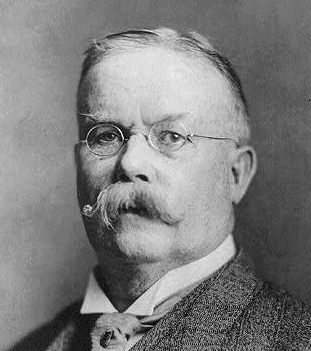

James McParland in the 1880′s

Infiltration and executions

Gowen’s most successful step was the employing of Pinkerton detective James McParland. Using the alias James McKenna, he utilised his county Armagh birthplace to integrate himself into the Irish Community. The majority of the Irish were illiterate and poorly educated, and the fact that McParland/McKenna could read and write gained him access into the local organisations.He became secretary of the local AOH and close to the militants. It later emerged that his two brothers were also involved in this infiltration.His investigation and testimony would lead directly to the trial and execution of twenty alleged ‘Mollies’. During his years of subterfuge, information provided by McParland was used by company vigilantes to identify targets for murder. McParland had no scruples about this, but had a crisis of conscience when the wife of an alleged Molly Maguire was shot dead. In a letter of resignation (soon to be withdrawn) he asked “What had a woman to do with the case—did the ‘Molly Maguires’ in their worst time shoot down women?” and added that “I will no longer interfere as I see that one is the same as the other and I am not going to be an accessory to the murder of women and children. I am sure the ‘Molly Maguires’ will not spare the women so long as the Vigilante has shown an example.”

His conscience didn’t trouble him for too long. His actions would lead to the deaths of twenty alleged men ,including John Kehoe (also known as ‘Black Jack’), branded as ‘King of the Mollies’. Aside from McParland’s testimony, paid informers and pardoned criminals provided the ‘evidence’, and Gowen himself had been appointed special prosecutor.

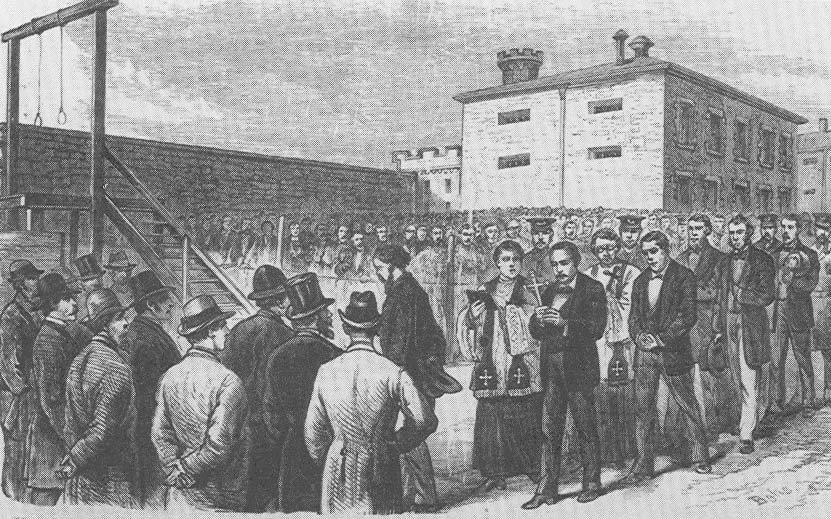

Execution of John Kehoe

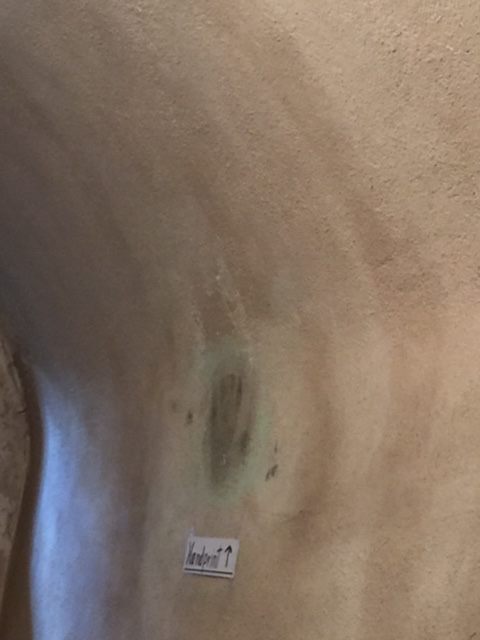

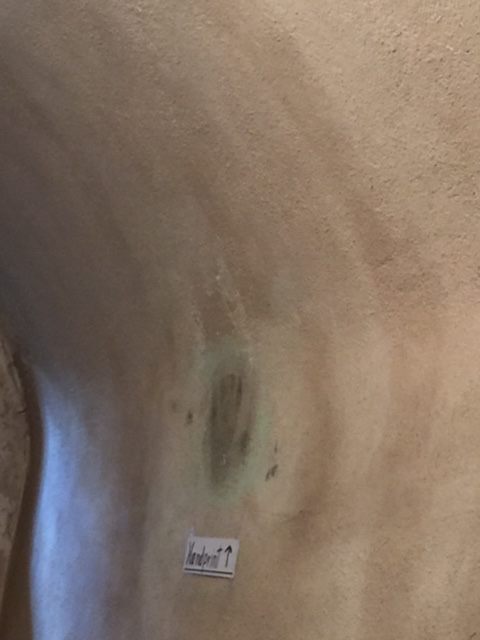

Many of those executed proclaimed their innocence until the end. Alexander Campbell slapped a muddy handprint on the wall of his cell and promised that “It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man”, and can still be seen today. A century after his death, John Kehoe received a posthumous pardon from the Pennsylvania governor Milton Shapp in 1979.

Alexander Campbell handprint as photographed by Playwright John Kearns

Failure follows success

It is possible that some of those hanged were involved in militant activity, but it was for the ‘crime’ of self organisation that they were really ‘guilty’. Gowen later promoted a similar conspiracy relating to the Knights of Labor but was unsuccessful. He died from a gunshot wound to the head in 1889. It would be wishful thinking to accept the theory that this was an act of Molly vengeance; it seems most probable that he committed suicide.

McParland also continued his crusade to undermine the growing trade union movement in the rail and mine industries,including attempts in Kansas, Colorado and Idaho. He took on the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Despite placing an agent on the unions legal team,he failed spectacularly in a trial aimed at securing the execution of the WFM leaders. All were acquitted, including Big Bill Haywood. McParland was now notorious, and one labour leader characterised him thus: “He will do anything, no matter how low or vile, to accomplish his purpose”. He died in 1919 of natural causes.

James McParland in later life

Myth versus truth

The full truth of the Molly Maguires is probably lost to history. The fact that the Irish men involved were mostly illiterate, (and in a secret society), means that they left no accounts of their own. Sensationalist journalism, propaganda, detective reports, trial testimonies and popular ‘histories’ published by the Pinkerton Agency all exist , but tell the story from the other side.

Some believe that the ‘Mollies’ were a fiction, playing on anti Irish/Catholic bigotry to justify the smashing of the WBA and A.O.H, two lawful organisations. There are good reasons to believe this – any union was anathema to a robber baron, and Jack Kehoe , a community leader, intelligent, and willing to throw his hat into the political arena, could have very easily created a power block among the Irish miners.

However while the ‘Molly’ threat was undoubtedly exaggerated and manipulated by Gowen and McParland, it is not credible to state that no such organisation existed. Whether as an oath bound secret society or a loose association of militants, linked or not with other organisations, there is no doubt that they existed in some form and engaged in violent action. Creating the impression of an ever present and all powerful movement would have been an appropriate tactic to adopt.Given the circumstances of the time and district, it is clear that those involved in ‘Molly’actions would also be members of both the AOH and WBA, which does not mean that all were part of one unified grouping.

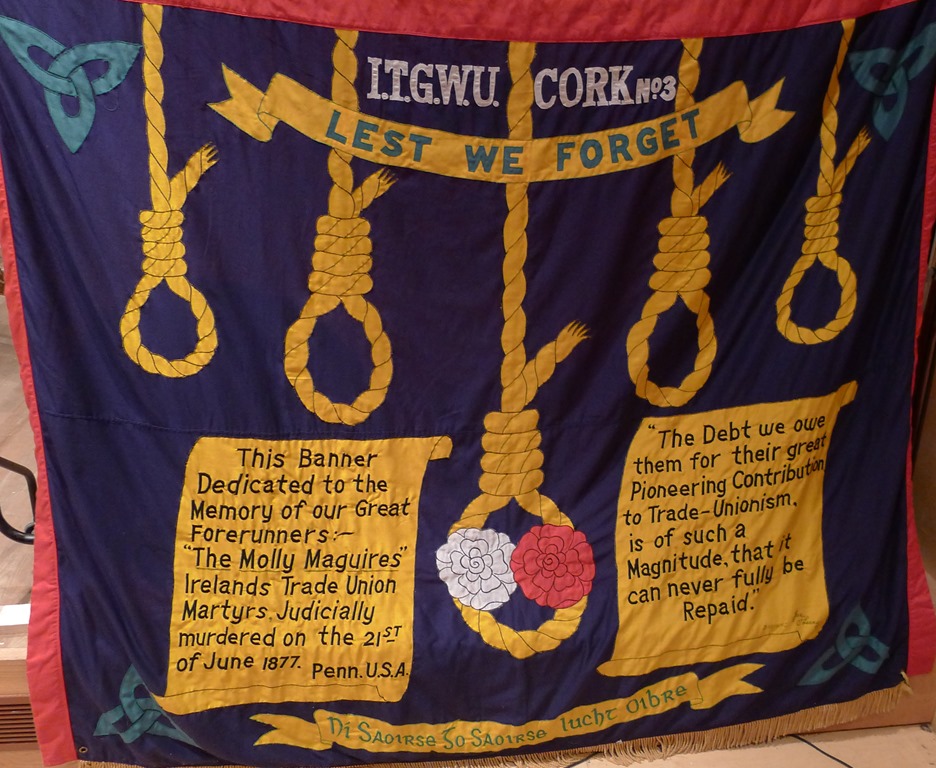

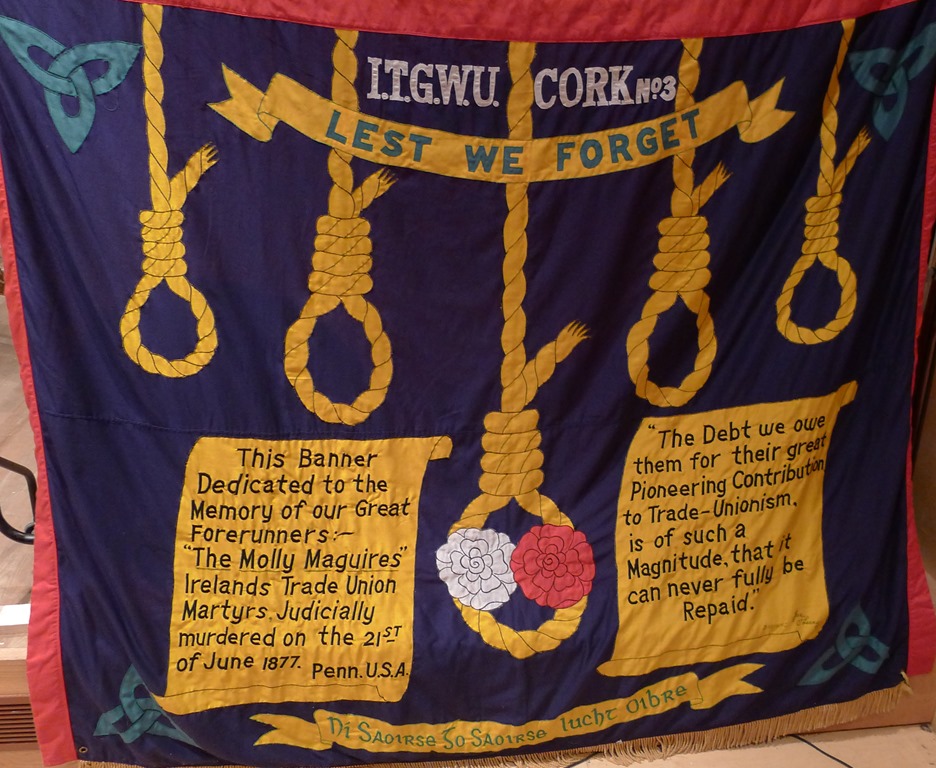

Remembered by the Irish Trade Union movement

Martyrs to the cause of Labour

The Irish immigrants were thrown in at the deep end of the industrial revolution, part of the new proletariat and combatants in a bitter class war. They responded in a manner consistent with their own traditions and history of struggle.

No matter which way we interpret events or judge those involved, we must remember that twenty men were hanged. They were casualties in a class war and are rightly recognised as working class martyrs both in Ireland and America.When Kehoe received his pardon in 1979, Governor Shapp said all Pennsylvanians should pay tribute to “these martyred men of labor.”

Powerful statue at Molly Maguire Park , Pennsylvania

“Sons of Molly Maguire” , written by John Kearns and directed by Dara Carolan received it’s Irish premiere as part of Mayfest 2017 at the Liberty Hall Theatre on Wednesday & Thursday 10th and 11th May @ 8pm .

Two additional performances also took place at the Sean O’Casey Theatre , East Wall on Tuesday & Wednesday 16th and 17th of May @ 8pm .