Oct 02

Croke Park CoderDojo – Classes begin

Croke Park Stadium CoderDojo

CoderDojo computer coding classes are held in Croke Park for children aged between 7 and 17 who live within a 1.5km radius of the stadium.

Children must be accompanied by a parent or guardian to each class.

Entry to the class is by ticket only and tickets are made available here on Eventbrite every Wednesday morning for the following week’s class.

Contact Julianne Savage in Croke Park jsavage@crokepark.ie if you’d like more information.

Or see the following event page :

https://www.eventbrite.ie/e/croke-park-coderdojo-tickets-13406221369

Sep 21

EAST WALL YOUTH – CLUB TIMES (from September 2014)

Current club times for East Wall Youth , at St. Mary’s Youth Club :

Drop-in Clubs:

Mondays:

5.30 – 7.00pm ……………………….. Early Club (ages 9 – 12) girls& boys

7.30 –9.00pm ……………………….. Late Club for teenagers (13+) Boys & Girls at secondary school level

9.15 – 10.15pm …………………….. Night Owls Club (ages 15+) Girls & Boys

Wednesdays:

5.30 – 7.00pm ……………………….. Early Club ages 9 – 12girls& boys

7.30 –9.00pm ……………………….. Late Club for teenagers (13+) Boys & Girls at secondary school level

Club facilities include:- games, art & crafts, play station, music & dance room, TV, pool, snooker, fuzz ball, table tennis, new computer room with internet access, Wii and occasional films.

We have new guitars and will soon be offering guitar lessons – watch this space!!

Football Clubs

at St. Mary’s Youth Club Outdoor Pitch

Mondays & Wednesdays:

4.00 – 5.00pm ……………………….. Under 9s Girls & Boys Football Club (free)

6.00 – 7.00pm ……………………….. Under 15s Boys Football Club

8.00 – 9.00pm ……………………….. Under 18s Boys Football Club

All clubs have an entrance fee of €1 (unless noted otherwise)

Sep 13

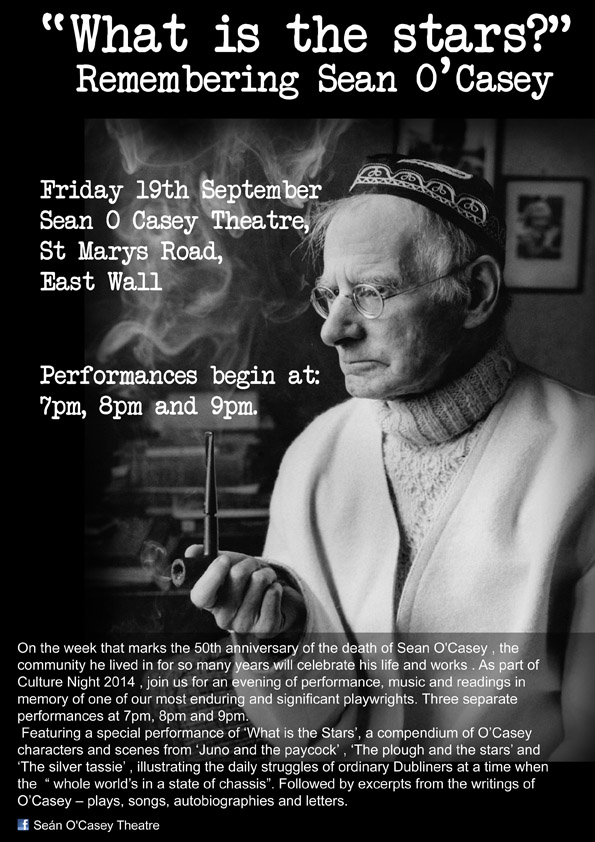

Sean O’Casey , the Hawthorn and the ‘Dung Dodgers’

“I thought that no man liveth and dieth to himself, so I put behind what I thought and what I did , the panorama of the world I lived in- the things that made me.” Sean O’Casey (1948)

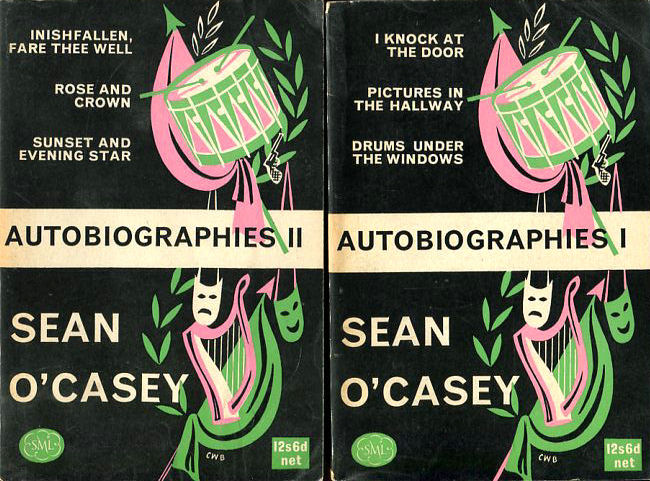

Between 1939 and 1955 Sean O’Casey published six volumes of Autobiography. The first three in particular contain much about his life as a North Dock resident. Throughout this anniversary year, marking 50 years since his death, we intend to present short extracts from these works, concentrating on sections which are most relevant to the area. In this excerpt we find young Sean (Johnny) relaxing and day-dreaming on Hawthorn Terrace (the family lived at number 25). But the peace and quiet is soon interrupted by a visit from the ‘Dung dodgers’ , sending the women folk into a flurry of activity . These events took place in the 1890′s .

“…he hated the smell of beer, and loved the smell of the hawthorn tree. The spice of Ireland, Ireland’s Hawthorn tree. And this grand tree was theirs. Right at the top of the little street it stood for everyone in the street to see. The people of the street were always watching it, except in winter when it was bare and bony, cold and crooked. But the minute it budded, they took their eyes to it, and called it lovely.

Th’ hawthorn tree’s just beginnin’ to bud, someone would say, just beginnin’, and the news would go from one end of the street to the other. Th’ hawthorn’s buddin’ at last. Did yeh hear? No; what? Why, the hawthorn tree’s burstin’ with buds; I seen Mrs. Middleton a minute ago, and she says the hawthorn tree’s thick with half-openin’ leaves, so it is. And the first flower would send them into the centre of a new hope, for the praties were dug, the frost was all over, and the summer was comin’ at last. And no cloud of foreboding came till autumn’s dusky hand hung scarlet berries on the drowsy tree, and all the people, with their voices mingling, murmured, the long dreary nights, the reckless rain, the chilly sleet, the cowld winds, an’ all the hathred in winther is comin’ again.

Johnny turned his thoughts away from the thought of winter, and gazed again at the pearly-blossomed hawthorn tree. Here, some day, in the quietness of a summer evening, in a circle of peace, it would be good to sit here with curly-headed Jennie Clitheroe, nothing between them save the sweet scent from the blossoms above. It would be good, good, better, best, positive, comparative, superlative, an’ God would see that it was good, and would no longer repent that He had made man in His own image.

If he wanted, now, he could easily climb up and break off a branch to bring the scent of the hawthorn tree right into his own home. But all the people round said it was unlucky to bring hawthorn into a house, all except his mother, who said that there was no difference between one tree and another; but, all the same, Johnny felt that his mother wouldn’t like to see him landing with a spray in his hand. It was all nonsense, she’d say, an’ only a lively superstition; but you never can tell, and people catching sight of hawthorn in a house, felt uneasy, and were glad to get away out of it. So it was better to humour them and leave the lovely branches where they were. Leave it there, leave it fair, and leave it lonely. Sacred to the good people, Kelly said; but he was only up a few years from the bog. They, the fairies, danced round it at night, he said, gay an’ old an’ careless, they danced round it the livelong night, and no matter how far away they were, they heard it moan whenever a branch was broken.

From under the shade of the hawthorn tree Johnny looked down the little street, and saw a stir in it. Down at the far end he saw what looked like little hills, one after the other, on each side of the narrow way. Women, opening doors and standing on the thresholds, were gazing about near where the little hills lay. I lift up mine eyes unto the hills.

Suddenly, he heard a call of Johnny Cassidy! Johnnie Cassidy! He turned his gaze to the right, and, a little way down the street, saw Ecret with hands cupped over his mouth to make his voice travel farther, calling Johnnie Cassidy, your mother wants you!

Lower down still, he saw Kelly, with his hands cupped over his mouth, calling out louder than Ecret, Johnny Cassidy, Johnny Cassidy, your mother wants you quick! The dung-dodgers are here!”

“ Johnny hated these dirt-hawks who came at stated times to empty out the petties and ashpits in the backyards of the people, filling the whole place with a stench that wouldn’t disappear for a week. He sighed, and, leaving the shade of the hawthorn tree, hastened as slow as he could down the street to join his mother.

The whole street was full of vexation and annoyance. Women standing at their doors this side of the street were talking to women standing at their doors on the other side of the street, and murmuring against the confusion that had come upon them, upsetting all they had to do till this great fast of the purification had come to an end.

– Always comin’ down on a body at an awkward time, managing to present themselves when the families were in the throes of doin’ important things. If they didn’t come on washin’ day, they came when the clothes were flutterin’ on the lines to dhry; an’, if they didn’t come then, they were knockin’ at the door when the few white an’ delicate coloured things a body had were bein’ spread out to be carefully an’ tenderly ironed.

– It’ud vex th’ heart of a saint, said Mrs. Cassidy, over to Mrs. Middleton, an’ she standin’ on the kerb in front of her hall door, comin’ just when me two boys are home for a little leave. They’ll come thrampin’ in an’ go thrampin’ out, leaving the dirt of petty an’ ashpit ground into the floor of the room an’ the hall, an’ the two boys expectin’ everything to be spick an’ span, an’ a special ever-ready attention to them as a little compensation for the constant right turn an’ quick march of the barrack square.

– It’s a rare hard an’ ever-endin’ fight we have, said Mrs. Middleton from her door on the opposite side of the street, again’ the dust an’ dirt we gather around us in the course of our daily effort to keep things in ordher. Here I am, with the youngsters all ready, bar the puttin’ on of their caps, to take them over to me sisther’s I haven’t seen for months, living on a green patch on the side of the Tenters’ Fields, who’ll be waitin’ for our arrival, an’ sthrainin’ her ear for a knock at the door, the time she’s gettin’ ready a pile o’ pancakes for the gorgin’ of the kidgers she sees so seldom.

– An’ the dark row that’ll shine over the whole place, went on Mrs. Cassidy, heedless of what Mrs. Middleton had told her, if as much as a speck violates the tender crimson of the boys’ tunics, issued undher a governmental decree of a spotless appearance, so that no scoffer may be given a chance to pass a rude remark about the untidiness of the Queen’s proper army.”

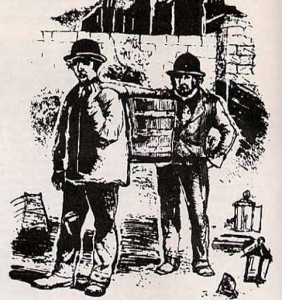

Dublin children from the same era .

Dublin children from the same era .

“ – Now, looka the poor Mulligans, said Mrs. Middleton, meandering across the road to stand on the pavement a few feet from Mrs. Cassidy, watching her trying to pry up the tacks that held the faded oilcloth to the floor, shoving an old knife-blade under the tack heads, and gently forcing them out so as not to make the oilcloth any worse than it was, looka the poor Mulligans, with their four chiselurs down with the measles, two o’ them lyin’ in the room the dung-dodgers’ll have to pass through, with the doctor shakin’ his head over one of them, an’ the mother’s soul-case worn out runnin’ from one to the other, thryin’ to ward off any dangerous thing that may be hoverin’ over their little heads, while the dung-dodgers are busy filthifyin’ the whole place, an’ she only havin’ two hands on her to tend the children an’ clean up the mess when the dung-dodgers are gone, before she dare sit down in the shade of a little less to do.

– Well, we’ll only have to give her a hand when we’re a little free ourselves, said Mrs. Cassidy, an’ save the poor woman from suddenly dhroppin’ outa her standin’.

– An’, went on Mrs. Middleton, looka Mrs. Ecret, aftherpaintin’ her hall door only yestherday, with a tin o’ paint her boy providentially found – when no-one was lookin’, I suppose – an’ varnishin’ it well to finish it off, all afthercomin’ to grief with them tearin’ their baskets of dirt against it, comin’ in an’ goin’ out, refusin’ to wait till the door was decently dhry, an’ leavin’ it lookin’ for all the world like the poor little maiden all forlorn who married the man all tattered an’ torn. Though I’d say sorra mend her, goin’ about like the cock of the south because her hall door was the only one on the sthreet that had had a lick o’ paint on it since Noah first saw the rainbow. But there’s always a downfall in front of them who strive to ape the airs of the quality.

Mrs. Cassidy gazed at the oilcloth she was lifting, and sighed resignedly.

– This is the last time I’ll get this to stand the sthrain, she said. It’s fare you well, me lady, the next time I thry to get it up. You’re perfectly right, she added, turning towards Mrs. Middleton, for it’s a bad thing to allow yourself to crow over worldly possessions, for we brought nothing into the world, an’ it’s certain we can take nothing away.

– Only a good character, murmured Mrs. Middleton, only a good character, an’ God knows it’s hard enough to take that away with us, either. Here’s your Johnny, now, to help you, with a tiny sprig o’hawthorn in his hand. Don’t let him bring it into the house, she said seriously, bending her head close to Mrs. Cassidy, for it’s the same may bring with it the very things we thry to keep at a distance.

– An’ what does it bring into the house with it? asked Johnny.

– Things that toss in a golden glory to a distant eye, said his mother, and, at the touch of a human hand, turn to withering leaves whirling about in a turbulent wind.

– And, said Mrs. Middleton, things that swing in a merry dance to a silver song that changes, quick as thought, to a dolorous sigh and a thing stretched out in a white-wide sheet in the midst of a keen an’ the yellow flame from a single candle. So leave your little twig o’ hawthorn on the window sill outside, alanna.

– Ay, Johnny, said his mother, leave it there, for though it is only roman catholics who cherish such foolish fables, it’s always safer to be on your guard.”

Extract from “Pictures in the Hallway” (1942)

All six volumes of Sean O’Casey Autobiographies, republished by Faber and Faber, are currently available in both print and kindle editions.

If you have a favourite Sean O’Casey extract please bring it to our attention.

Contact us at eastwallforall@gmail.com

Sep 07

Sean O’Casey, shopping with his Ma, and feckin’ the bacon & eggs

“I thought that no man liveth and dieth to himself, so I put behind what I thought and what I did , the panorama of the world I lived in- the things that made me.” Sean O’Casey (1948)

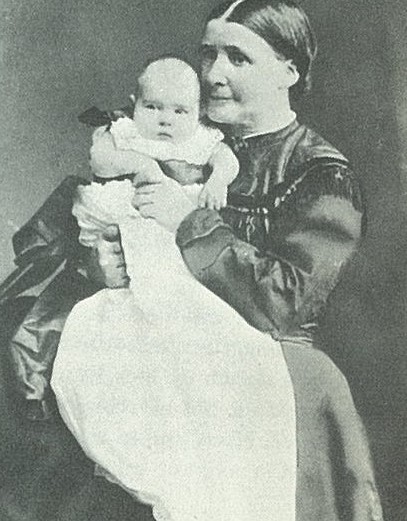

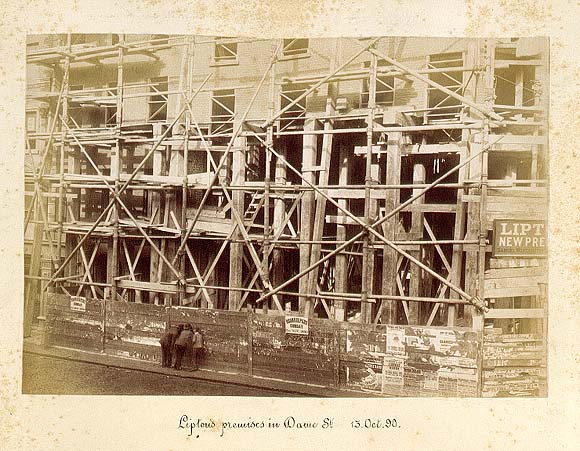

Between 1939 and 1955 Sean O’Casey published six volumes of Autobiography. The first three in particular contain much about his life as a North Dock resident. Throughout this anniversary year, marking 50 years since his death, we intend to present short extracts from these works, concentrating on sections which are most relevant to the area. In these excerpts we find the young O’Casey (Johnny) making a nuisance of himself as a reluctant companion to his mother (Susan Casey) on a shopping trip in the City Centre . In the second excerpt we join them for a purchase in Liptons (of Dame Street) , a quick listen to a street-singer and a bonus for the family when Johnny empties the Kit-bag . We believe that Sean is probably aged around 10 years old at this time , and Susan is in her 50′s (as in picture with Grand-daughter).

“ How he hated the journey, and how tired the walking made him, for there was nothing stirring, nothing in the walk to make his feet light or lift them in a dancing step; often his mother had to tell him not to drag his feet, but to walk like an ordinary human being. Then, without knowing, he’d hang on to his mothers arm till she’d cry out, oh don’t be draggin’ outa me like that; can’t you walk on the legs that God has given you? He’d take his arm away, and journey on through the wilderness of streets, shuffling his feet, and lagging a little behind.

What wouldn’t he give, now, for a good topcoat, an’ he goin’ along Dorset street, facin’ the spittin rain an’ the penethratin’ wind, whippin’ in his face an’ stabbin him right through his coat and trousers, an’ thattered shirt, making him feel numb an’ sick as he dragged himself along afther his mother, protectin’ himself as well as he could be holdin’ the kit-bag spread out like a buckler in front of his breast.

He kept his eye on his mother ploddin’ along in front of him, carryin’ a basket an’ an oilcan, dhressed in her faded an’ thin black skirt an’ cape, her shabby little bonnet tied firmly undher her chin, the jet beads in it gleamin’ out of it as bright as ever; an’ she steppin’ it out, hell-bent for Liptons , ignorin’ all the shops that lined the way , stuffed with all sorts of fine an’ fat goods that God never meant her to have.”

“The shop was crowded, full of white-coated counter-jumpers handin’ out tea an’ sugar an’ margarine as swift as hands could lay hands on them; with men in brown overalls trotting along pushing mountains of tea an’ sugar in packages on little throlleys, moving silently and cunningly through the crowded shop, to fill up the vacancies on the shelves.

They waited their turn to get their seven pounds of sugar, a pound of tea for one an’ six, an’ a two-pound pot of Lipton’s special plum an’ apple jam; Johnny packing them in the kit-bag, while his mother slowly and feelingly put back sixpence change in-to the pocket of her skirt, strengthened with added lining to keep such treasures safe.

-Well, that’ll have to provide us with whatever else we may need for the rest of the week, she murmured, lettin’ the sixpence go at last when she felt it settle in the bottom of her pocket.

Johnny swung the kit-bag over his shouolder, an’ he an’ his ma manoeuvred to the door through the people thronging the shop; pausing to see themselves in the mirrors, looking like fat pigs, bulging cheeks, great round bellies, an’ enormous bodies, showing how great the stuff was that Lipton’s sold; then the pair of them plunged once more into the dark night, the spitting rain, and the biting breeze; Johnny feeling all these trials less when he remembered the egg in his pocket and the bacon in the bag.

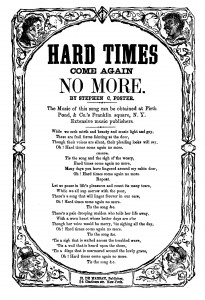

Out in the street, moving forward in the kennel, was an old grey-bearded man, with a creaking voice, singing dolefully to the busy street. The collar of his coat was pulled up, as high as it could go, and his neck and chin were suck down in it as low as they could go to shelter them from the wind and the rain; but when high notes came, the head had to be lifted to get anywhere near them, so the thin neck rose out of its cosy nest, to sink back again when the high notes were over, and the low notes came back. Quite a number of people paused in their hurry, searched in purse or pocket to hand out a penny; and Johnny felt envious that money could be so easily earned be the cracked singin’ of

Let us pause in life’s pleasures, an’ count its many fears,

While we all sup sorrow with the poor,

Here’s a song that shall linger for ever in our ears,

Oh, hard times, come again no more.

‘Tis the song, the sigh of weary,

Hard times, hard times, come again no more;

Many days have you lingered around my cabin door,

Oh, hard times, come again no more!

-Since we haven’t anything to give him, it isn’t fair to listen, said his mother, pulling the arm of the pausing Johnny.

When they got home again, Johnny spilled the sugar, tea, and jam out on the table. Then he put the lump of bacon and the egg right where his mother could see them when she turned round after taking off her wet things.

When she turned, she stared.

-How, in the name o’ God, did these things ever creep into the kit-bag? she asked.

-I fecked them, said Johnny gleefully. When the dhrunken man fell an’ scattered things, I fecked them as I passed.

-A nice thing if you’d been caught feckin’ them, she said, in a frightened voice. Never, never do the like again. D’ye know, had you been nabbed, it ‘ud have meant five years or more in a re-formatory for you? Never do it again Johnny. Remember what you’ve been taught: Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on; for the life is more than meat, an’ the body than raiment; and your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have been of all these things; so keep your hands from pickin’ an’ stealin’, for the future; and she carefully placed the bacon and the egg in the press.

Johnny sat silently by the fire, drying his damp trousers. After a few minutes he saw his mother putting on her bonnet and cape.

-Where you goin’ now, Ma? he asked.

-I’m goin’ out to get a couple o’ nice heads of cabbage, with the sixpence I’ve left, to go with the bacon tomorrow, she said.”

Extracts from “I knock at the door” (1939)

All six volumes of Sean O’Casey Autobiographies, republished by Faber and Faber, are currently available in both print and kindle editions.

If you have a favourite Sean O’Casey extract please bring it to our attention.

Contact us at eastwallforall@gmail.com

Sep 01

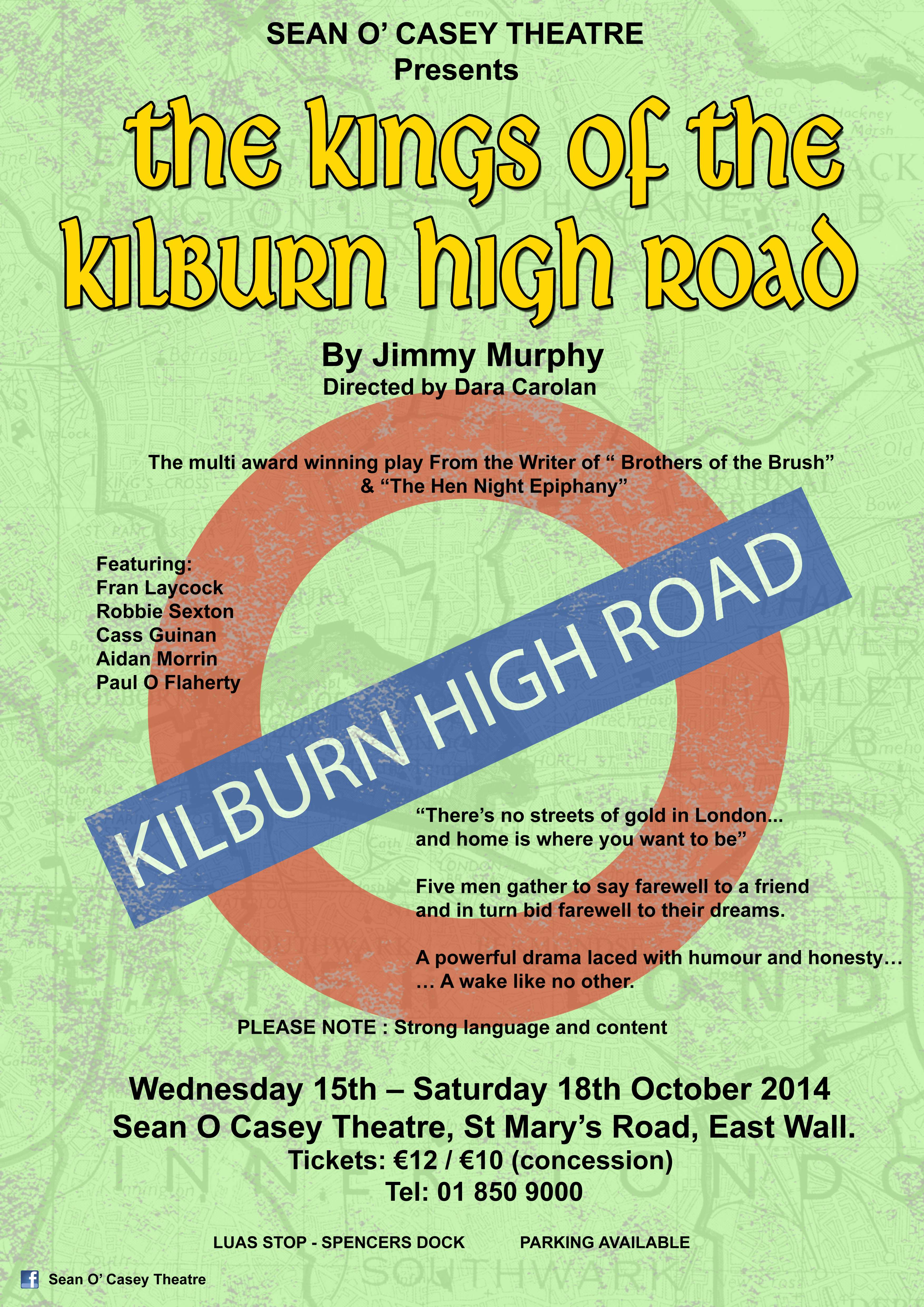

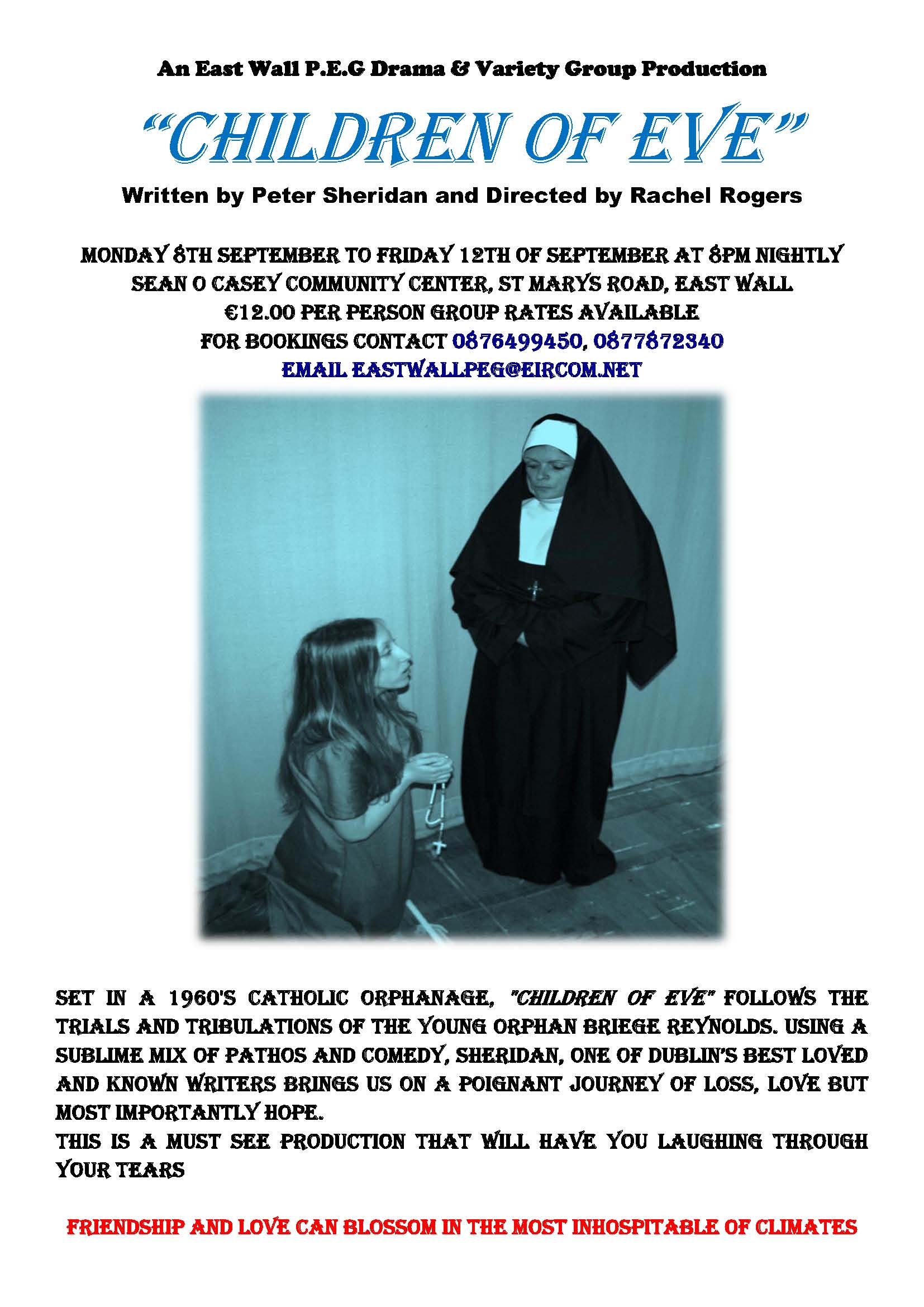

“CHILDREN OF EVE” – A play by Peter Sheridan .

The East Wall P.E.G variety and Drama Group are excited to present the brilliant play CHILDREN OF EVE written by Peter Sheridan and directed by Rachel Rogers.

The East Wall P.E.G variety and Drama Group are excited to present the brilliant play CHILDREN OF EVE written by Peter Sheridan and directed by Rachel Rogers.

First performed in 1989 in conjunction with the Abbey Theatre, and set in a 1950′s catholic orphanage, Peter Sheridans “Children of Eve” follows the trials and tribulations of the young orphan Briege Reynolds. Using a sublime mix of pathos and comedy Sheridan, one of dublins best loved and known writers brings us on a poignant journey of loss, love but most importantly hope. This is a must see production that will have you laughing through your tears. Friendship and love can bloom in the most inhospitable of climates.

The Sean O Casey Theatre , St. Mary’s Road ,East Wall ,

September 8th to September the 12th @ 8pm nightly

Admission 12euro group rates available

for bookings contact 0876499450, 0877872340

Aug 28

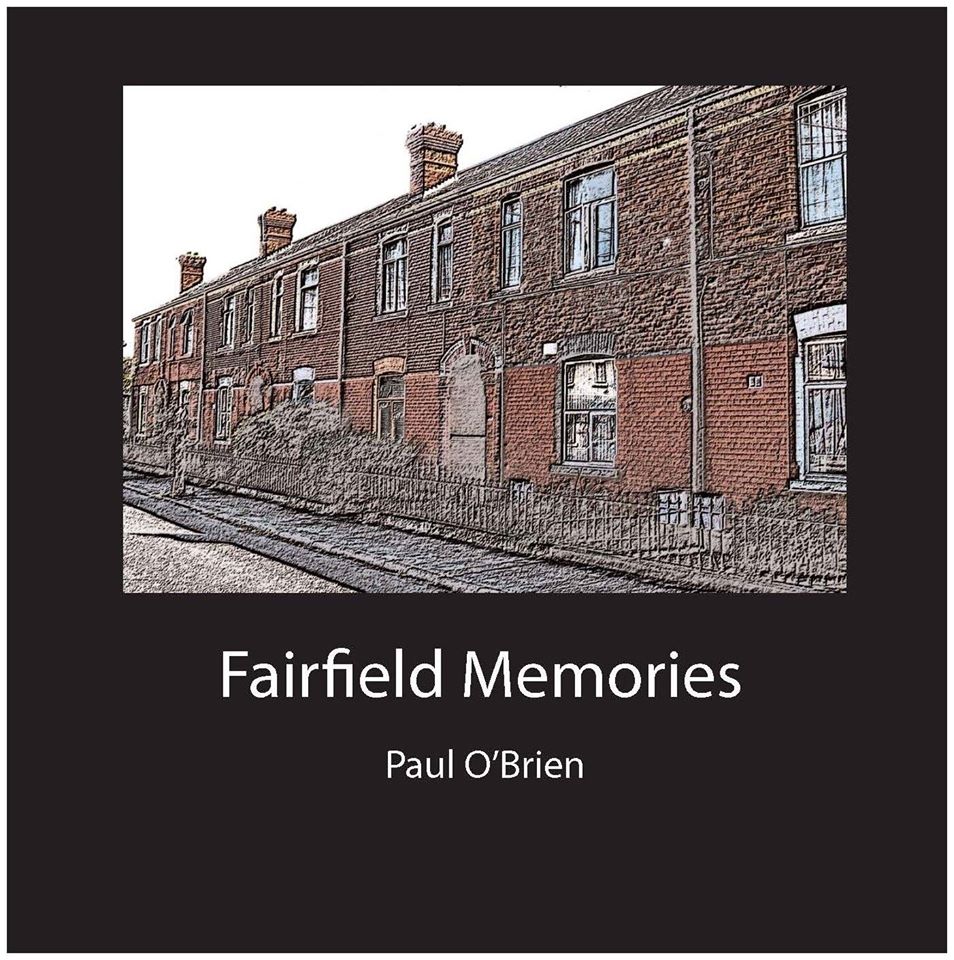

“FAIRFIELD MEMORIES” – CD launch at The Ferryman

“FAIRFIELD MEMORIES ” is the latest CD from Paul O’Brien , and will be launched this Saturday (30th August) at the Dublin Dockworkers Preservation Society heritage event at The Ferryman, Sir John Rogersons Quay, 8.30pm).

Paul will be well known to many of you , not just as ‘the local lad with the guitar’ but also as the musician behind the wonderful “Songs from the North Lotts” and “Port to Port” collections . Paul explains the importance of this latest work -

“I would like to let you all know a little about my latest CD “Fairfield Memories” When I was born my parents lived in a rented downstairs room on Fairfield Avenue and this is where I spent the first year of my life. They then moved to a house around the corner on the West Road, beside McArthur’s ‘wee’ shop. As a child I played on the Fairfield football team in the local street leagues and many of my school pals lived there, it was also part of my paper round. I was fascinated by the first twenty ‘apartments’ or flats on the avenue, small and very unusual for the area, indeed for Dublin. They are known locally as the ‘Scotch Buildings’. These apartments were built at the beginning of the twentieth century to house Scottish immigrant workers who came to work in the Dublin Dockyard ship building company, though I was not aware of that then. I felt, and still feel, an attraction to this part of the street perhaps simply because it is so unique and in a way represents my childhood. I visit the avenue regularly to wallow in the memories of the boy I was when that area between the railway and the sea was my whole world.”

”This is a collection of songs that are linked to this area and to my family members. Some I wrote many years ago, some more recently. All of them are based in one way or another on the feeling I get whenever I walk along Fairfield Avenue. The older songs are songs that I have not previously recorded but I had regularly played with my brother Gerry, who passed away in 2013. I felt it was time to make them available to all.”

“I’m glad you took the time

I’m glad I went along

I’m glad that I could make you cry

With the words of a song

You filled me in on all the things

That have happend in ‘Our Gang’s” lives

How some have dissappeared

And some ar friends for life

You said you hated changes

But that’s the way it is

And I’m sure that things were changing

Even when we were kids

How the freight trains

Made way for the Dart

And when they shut the lanes off

How it broke your heart “

Lyrics from “Fairfield Avenue” by Paul O’Brien

(“The forgotten history of the Dublin Docks” is a heritage event organised by the Dublin Dockworkers Preservation Society. Saturday 30th August, The Ferryman on Sir John Rogersons Quay, starting at 8.30pm. Will feature a short talk on a forgotten hero of the docks, and Paul will be performing some old favourites and material from “Fairfield Memories”. Dock workers memorabilia including coal shovels, dockers hooks etc. will be on display. All welcome to this FREE EVENT).