“I thought that no man liveth and dieth to himself, so I put behind what I thought and what I did , the panorama of the world I lived in- the things that made me.” Sean O’Casey (1948)

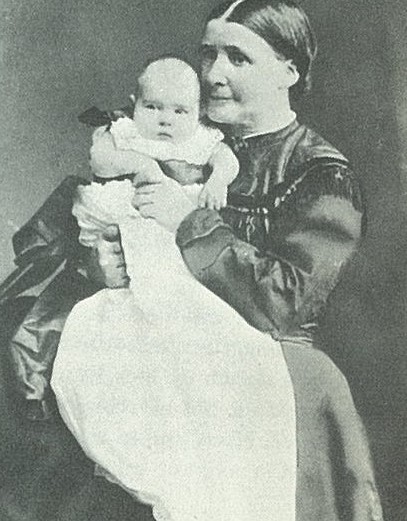

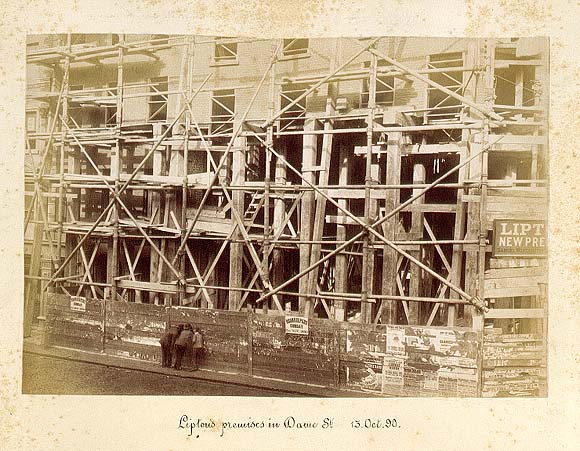

Between 1939 and 1955 Sean O’Casey published six volumes of Autobiography. The first three in particular contain much about his life as a North Dock resident. Throughout this anniversary year, marking 50 years since his death, we intend to present short extracts from these works, concentrating on sections which are most relevant to the area. In these excerpts we find the young O’Casey (Johnny) making a nuisance of himself as a reluctant companion to his mother (Susan Casey) on a shopping trip in the City Centre . In the second excerpt we join them for a purchase in Liptons (of Dame Street) , a quick listen to a street-singer and a bonus for the family when Johnny empties the Kit-bag . We believe that Sean is probably aged around 10 years old at this time , and Susan is in her 50′s (as in picture with Grand-daughter).

“ How he hated the journey, and how tired the walking made him, for there was nothing stirring, nothing in the walk to make his feet light or lift them in a dancing step; often his mother had to tell him not to drag his feet, but to walk like an ordinary human being. Then, without knowing, he’d hang on to his mothers arm till she’d cry out, oh don’t be draggin’ outa me like that; can’t you walk on the legs that God has given you? He’d take his arm away, and journey on through the wilderness of streets, shuffling his feet, and lagging a little behind.

What wouldn’t he give, now, for a good topcoat, an’ he goin’ along Dorset street, facin’ the spittin rain an’ the penethratin’ wind, whippin’ in his face an’ stabbin him right through his coat and trousers, an’ thattered shirt, making him feel numb an’ sick as he dragged himself along afther his mother, protectin’ himself as well as he could be holdin’ the kit-bag spread out like a buckler in front of his breast.

He kept his eye on his mother ploddin’ along in front of him, carryin’ a basket an’ an oilcan, dhressed in her faded an’ thin black skirt an’ cape, her shabby little bonnet tied firmly undher her chin, the jet beads in it gleamin’ out of it as bright as ever; an’ she steppin’ it out, hell-bent for Liptons , ignorin’ all the shops that lined the way , stuffed with all sorts of fine an’ fat goods that God never meant her to have.”

“The shop was crowded, full of white-coated counter-jumpers handin’ out tea an’ sugar an’ margarine as swift as hands could lay hands on them; with men in brown overalls trotting along pushing mountains of tea an’ sugar in packages on little throlleys, moving silently and cunningly through the crowded shop, to fill up the vacancies on the shelves.

They waited their turn to get their seven pounds of sugar, a pound of tea for one an’ six, an’ a two-pound pot of Lipton’s special plum an’ apple jam; Johnny packing them in the kit-bag, while his mother slowly and feelingly put back sixpence change in-to the pocket of her skirt, strengthened with added lining to keep such treasures safe.

-Well, that’ll have to provide us with whatever else we may need for the rest of the week, she murmured, lettin’ the sixpence go at last when she felt it settle in the bottom of her pocket.

Johnny swung the kit-bag over his shouolder, an’ he an’ his ma manoeuvred to the door through the people thronging the shop; pausing to see themselves in the mirrors, looking like fat pigs, bulging cheeks, great round bellies, an’ enormous bodies, showing how great the stuff was that Lipton’s sold; then the pair of them plunged once more into the dark night, the spitting rain, and the biting breeze; Johnny feeling all these trials less when he remembered the egg in his pocket and the bacon in the bag.

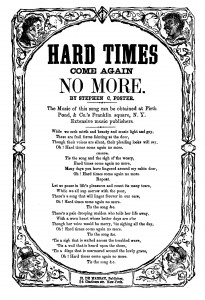

Out in the street, moving forward in the kennel, was an old grey-bearded man, with a creaking voice, singing dolefully to the busy street. The collar of his coat was pulled up, as high as it could go, and his neck and chin were suck down in it as low as they could go to shelter them from the wind and the rain; but when high notes came, the head had to be lifted to get anywhere near them, so the thin neck rose out of its cosy nest, to sink back again when the high notes were over, and the low notes came back. Quite a number of people paused in their hurry, searched in purse or pocket to hand out a penny; and Johnny felt envious that money could be so easily earned be the cracked singin’ of

Let us pause in life’s pleasures, an’ count its many fears,

While we all sup sorrow with the poor,

Here’s a song that shall linger for ever in our ears,

Oh, hard times, come again no more.

‘Tis the song, the sigh of weary,

Hard times, hard times, come again no more;

Many days have you lingered around my cabin door,

Oh, hard times, come again no more!

-Since we haven’t anything to give him, it isn’t fair to listen, said his mother, pulling the arm of the pausing Johnny.

When they got home again, Johnny spilled the sugar, tea, and jam out on the table. Then he put the lump of bacon and the egg right where his mother could see them when she turned round after taking off her wet things.

When she turned, she stared.

-How, in the name o’ God, did these things ever creep into the kit-bag? she asked.

-I fecked them, said Johnny gleefully. When the dhrunken man fell an’ scattered things, I fecked them as I passed.

-A nice thing if you’d been caught feckin’ them, she said, in a frightened voice. Never, never do the like again. D’ye know, had you been nabbed, it ‘ud have meant five years or more in a re-formatory for you? Never do it again Johnny. Remember what you’ve been taught: Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on; for the life is more than meat, an’ the body than raiment; and your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have been of all these things; so keep your hands from pickin’ an’ stealin’, for the future; and she carefully placed the bacon and the egg in the press.

Johnny sat silently by the fire, drying his damp trousers. After a few minutes he saw his mother putting on her bonnet and cape.

-Where you goin’ now, Ma? he asked.

-I’m goin’ out to get a couple o’ nice heads of cabbage, with the sixpence I’ve left, to go with the bacon tomorrow, she said.”

Extracts from “I knock at the door” (1939)

All six volumes of Sean O’Casey Autobiographies, republished by Faber and Faber, are currently available in both print and kindle editions.

If you have a favourite Sean O’Casey extract please bring it to our attention.

Contact us at eastwallforall@gmail.com