Dublin Docklands at War : 1914 to 1918

“The Whole world is in a state of chassis”

Dublin Port in a time of War: 1914 to 1918

“…his Majesty’s Government declared to the German Government that a state of war exists between Great Britain and Germany as from 11 p.m. on August 4, 1914.” With these words Ireland, as part of the United Kingdom at that time would inevitably find itself involved in the global conflict that would continue until November 1918.

The consequences for Cities and Towns across the thirty-two counties would be profound over this period, but for Dublin Docklands and the surrounding community the effects were immediate.

Much of Dublin Port was immediately seized by the military, with the North Wall extension and the Alexandra Quay taken over completely on the day war was declared. There was some easing of this militarisation over time but North Wall Extension remained under military control for the duration of the war. Quay-side sheds were converted for use by troops and built onto, and a section of the boundary wall was removed to allow the rail line to be expanded. Troops, animals, vehicles and equipment would pass through here on the way to the battlefields of France and Belgium.

Just days after Britain entered the war it is reported that 50,000 people gathered on the Quays to wave goodbye to reservists heading overseas “most enthusiastic for England, singing and playing God Save the King, an unheard of thing hitherto”. Troop movement would become a two-way traffic as the injured, the maimed and horrifically scarred would soon arrive back via North Wall. This began as early as September, with the first ship carrying over 600 wounded men. An average of 400 would have been on these ships. A letter writer to the Irish Times in 1915 would ask “Cannot something be done before the next hospital ship comes to Dublin to improve the awful surface of the roadway down the North Wall? Its present condition is a disgrace to our city. The arrangements today at the ships side and at the various hospitals were admirable and worked with perfect smoothness, but the passage from the dockyard gates to Carlisle Bridge must have been an inferno for badly wounded men”.

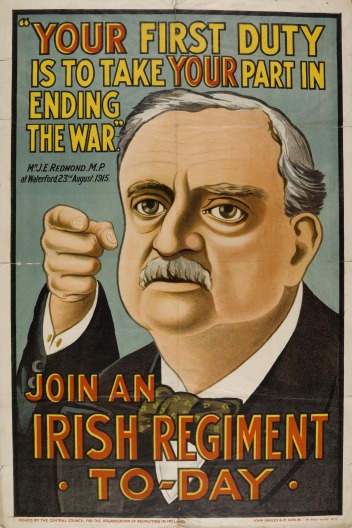

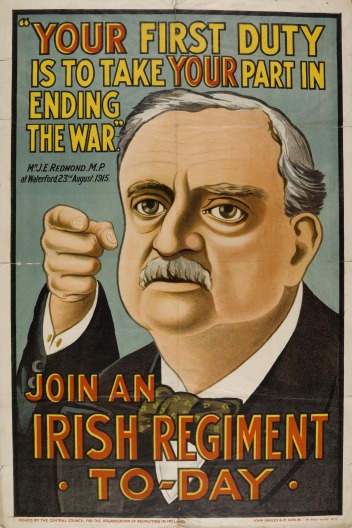

In the early years of the war, within the Docklands (as in other working-class districts) recruitment was high. The motivation for joining up was varied. These propaganda posters are clearly targeted at different potential recruits. Loyalty to the King and Great Britain was certainly a factor for some; while many Nationalist recruits would have hoped that their service would be rewarded with home rule after a British victory. The Docklands suffered from grinding poverty, substandard housing unemployment and casual labour – joining the forces was paid well,dependents received a separation allowance and many employers could be expected to favour former soldiers,so ‘Economic conscription’ was rife.Additionally, some workers remained black-listed after the industrial dispute of 1913. There are some reports of 200 Dockers, apparently known as “The Larkinites”, who joined the 7thBattalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The DMP claimed 2000 reservists from the ITGWU had re-joined their regiments to fight in France at the start of the war and in 1916 Transport Union organiser William Partridge stated that over 8000 had joined up nationally by March of that year.

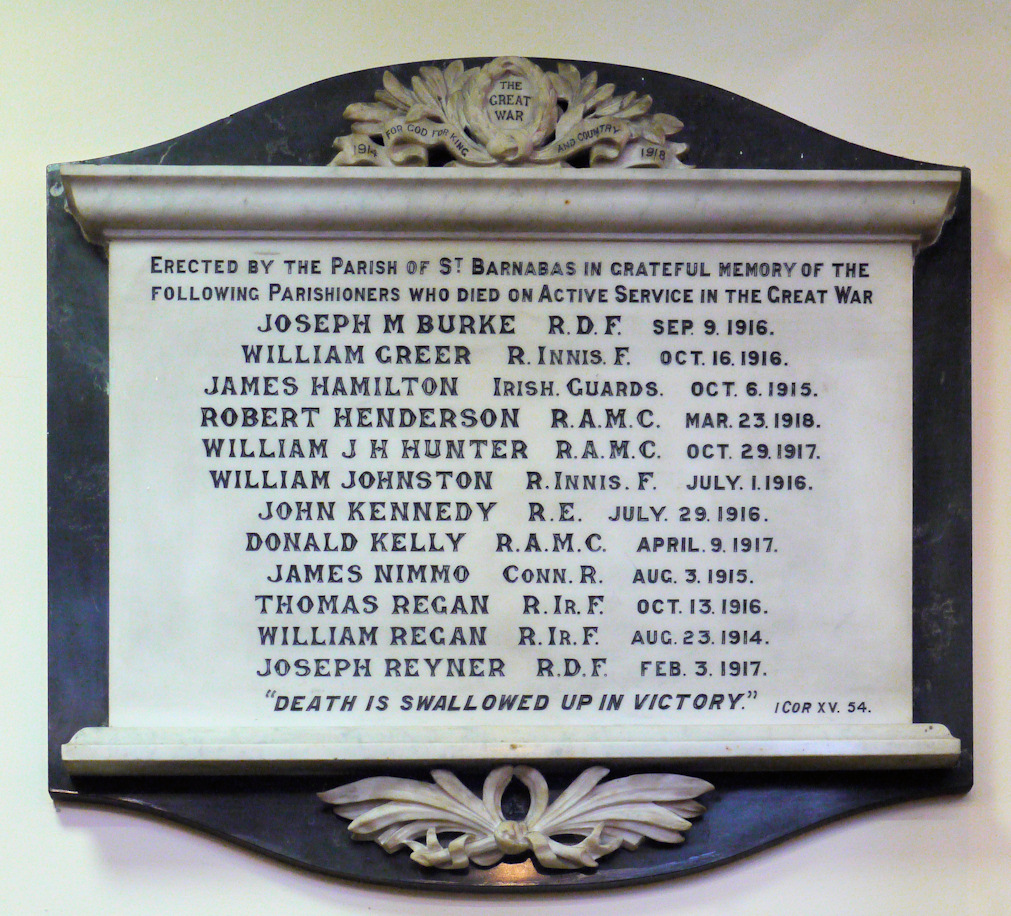

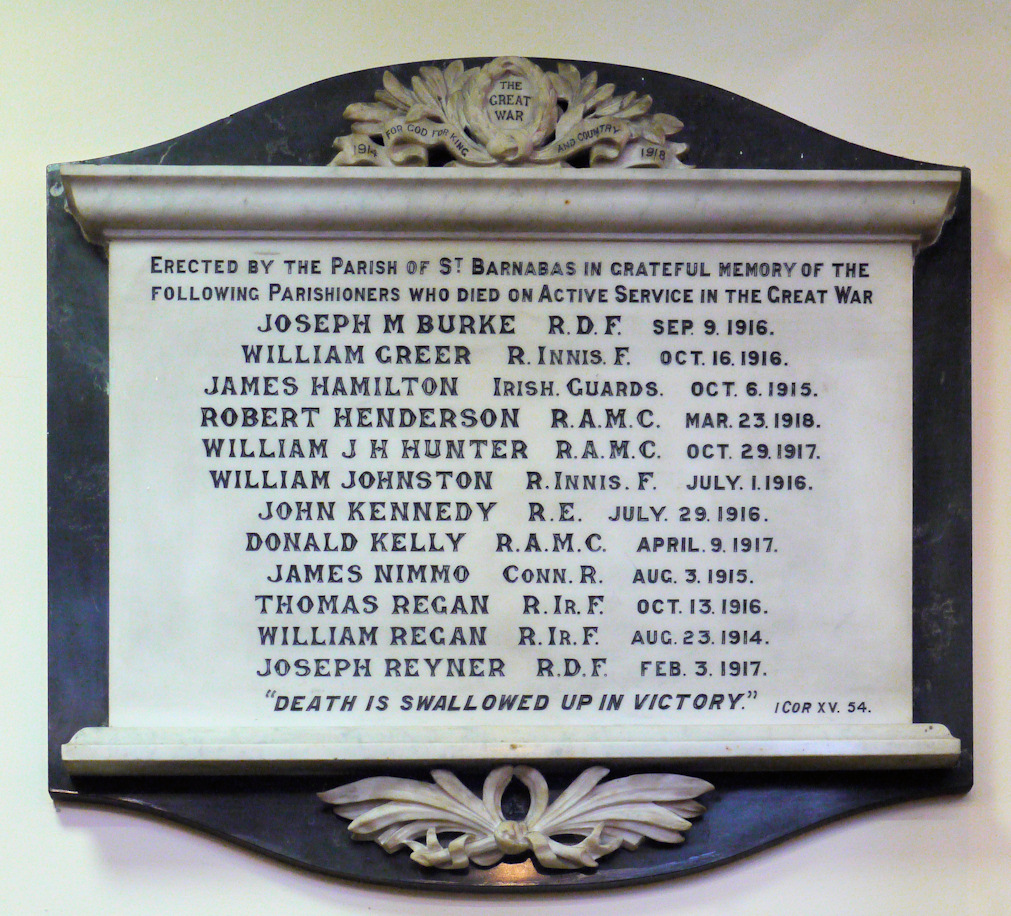

The earliest casualty from the Docklands we are aware of is 22-year-old William Regan; just three weeks after hostilities began, on 23rdAugust 1914. On this day, the Royal Irish Fusiliers lost 350 men at the Battle of Mons, Belgium, one of the first major engagements of the War. (Originally hailing from Cork, just over two years later his brother Thomas would die at Ypres,also serving with the Fusiliers).Many local employers enthusiastically supported the war effort. The London North Western Railway (LNWR) lost 13 staff associated with its North Wall Depot, killed in Europe.

While military control and restrictions remained in place for the duration, commerce continued, and for some local industrialists, business would be booming. In 1902, the Scottish born ship builder John Smellie was part of an endeavour to reinvigorate the industry here. He established the Dublin Dockyard Company and by the outbreak of war this had developed into a major local employer. A repair contract with the Royal Navy was signed as early as September 1914. They were soon producing pontoon bridges, floating targets to train gun crews, fitting ship gun platforms, depth charges, wireless cabins, mine laying appliances, telegraph poles, among other war related work. They would eventually be repairing torpedo damaged ships following U-boat attacks.

While military control and restrictions remained in place for the duration, commerce continued, and for some local industrialists, business would be booming. In 1902, the Scottish born ship builder John Smellie was part of an endeavour to reinvigorate the industry here. He established the Dublin Dockyard Company and by the outbreak of war this had developed into a major local employer. A repair contract with the Royal Navy was signed as early as September 1914. They were soon producing pontoon bridges, floating targets to train gun crews, fitting ship gun platforms, depth charges, wireless cabins, mine laying appliances, telegraph poles, among other war related work. They would eventually be repairing torpedo damaged ships following U-boat attacks.

Smellie had an ambitious plan to develop an aircraft manufacturing company here, but while he received the necessary licences he had difficulty acquiring a landing strip and abandoned this scheme. Instead he established the Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Company. Between 1915 and early 1919 the factory employed 200 women (mostly local) producing 648,150 shells during this period. Other local industries would also benefit from the conflict – such as T. &C. Martin’s, Timber Merchants, who would manufacture boxes and crates for military use.

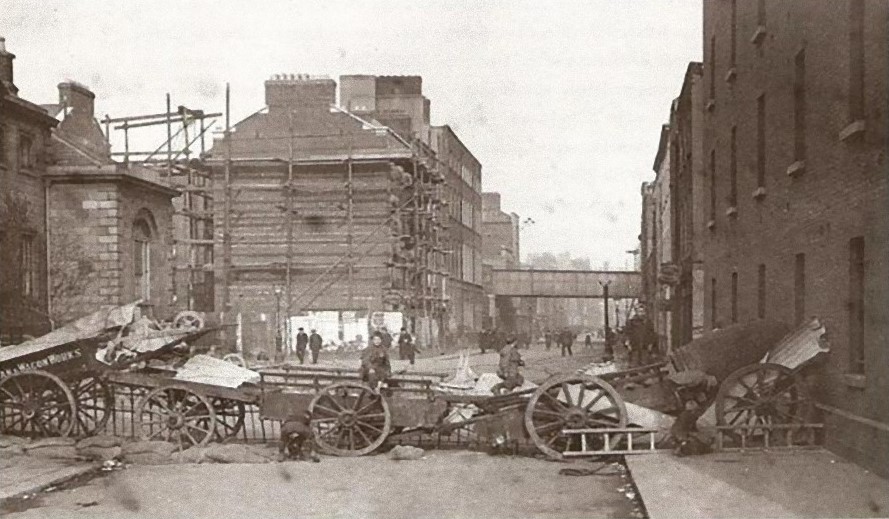

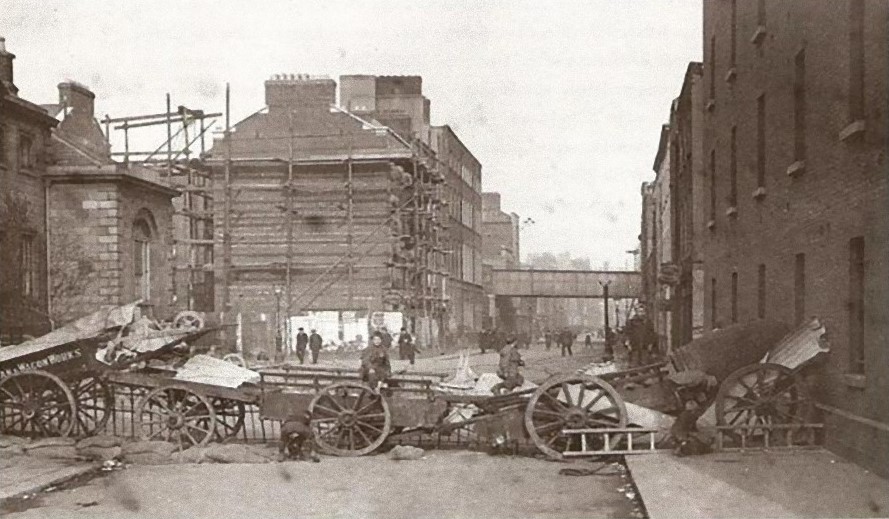

Easter 1916, the capital itself became a war zone, and Dockland residents would get to witness the horrors of combat first hand. Much of the North Dock was placed within a military cordon, and sniper fire and deadly machine gun bursts would become a daily threat. South of the River, Boland’s Mill was one of the main rebel garrisons, and some of the most intense combat of the week took place near to Mount Street Bridge. A small number of artillery shells were fired into both Grand Canal Quay and East Wall, and some tenements on City Quay shook so much from the booming guns on the Helga that they became unstable and dangerous to inhabit. Civilian casualties were significant in Ringsend, Pearse Street and in other residential areas on each side of the Liffey. The Dublin Port and Docks harbour master himself would have a narrow escape when his driver was shot beside him.

One of the other significant consequences of the war for Ireland and the Dublin Docklands was the use of submarine warfare. ‘Britannia Rules the Waves’ was no idle boast, and once war was declared Britain’s superior sea power was immediately put to use. A naval blockade of Germany was implemented , and by November the North Sea was declared to be a War Zone, with any ships entering doing so at their own risk. A British designation of food as ‘contraband of war’ was controversial, giving them greater opportunity to challenge merchant vessels and also signalling a clear intention to starve Germany into submission. Germany would soon respond in kind. Britain, as an Island nation was more vulnerable to such a tactic. However, they had anticipated their blockade would restrict the Kaisers fleet, and while this was the case for surface vessels, it was the aggressive deployment of U-Boats that would almost be their undoing.

This led to Germany formally declaring a policy of ‘unrestricted warfare’ on 4th February 1915. “Germany now declares the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, to be comprised within the seat of war, and will prevent by all the military means at its disposal all navigation by the enemy in those waters. To this end it will endeavour to destroy, after February 18 next, any merchant vessel of the enemy which presents themselves at the seat of war above indicated, although it may not always be possible to avert the dangers which may menace persons and merchandise”

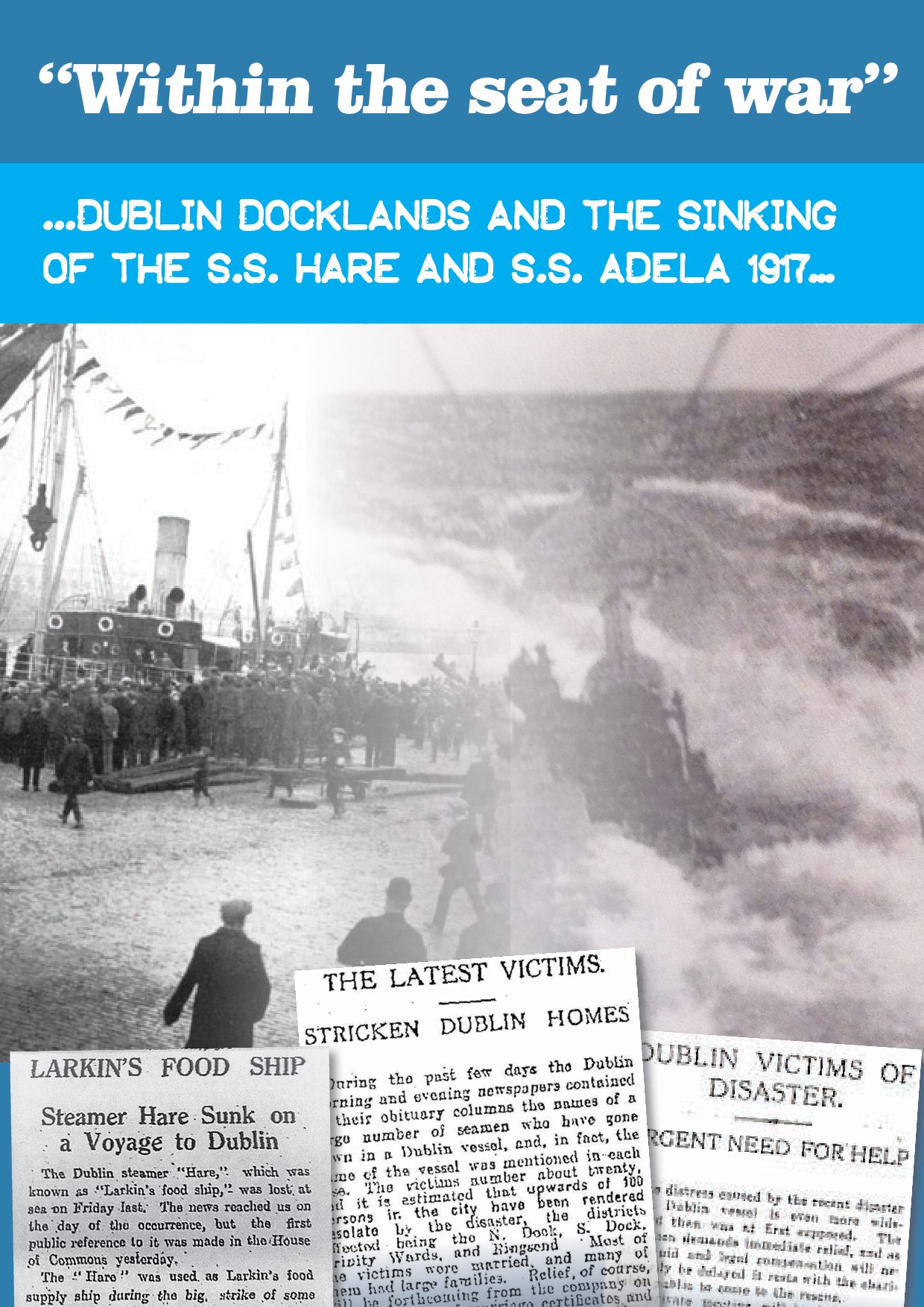

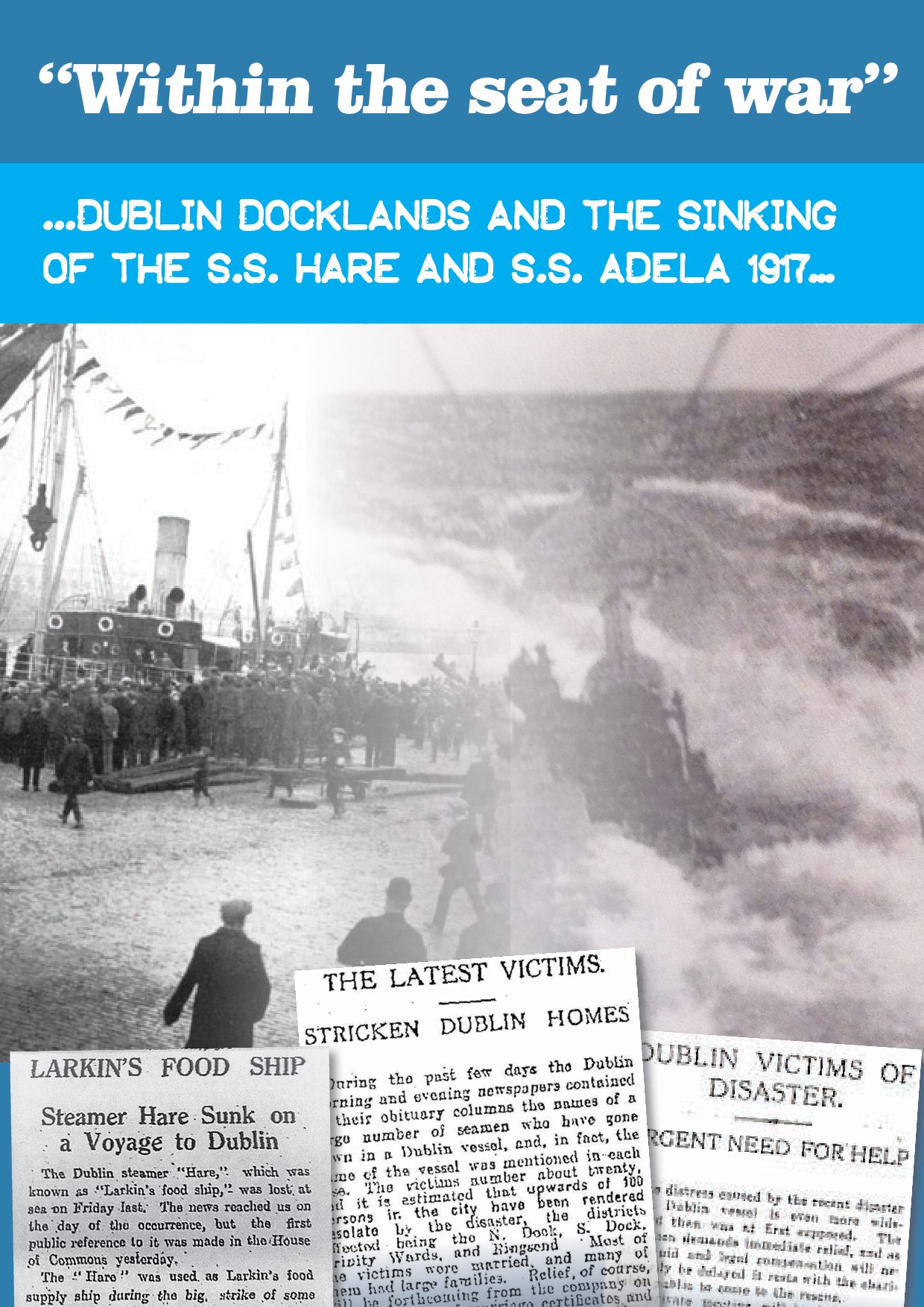

It was in the context of this policy that Dublin Port ships were targeted. These attacks intensified in 1917. Among the vessels lost that year was the WM Barkley, the first of the famous Guinness fleet . On the 20th October, just hours after it had set out destined for Liverpool it was sunk with the loss of five crew members , including Thomas Murphy from number 36 Sheriff Street.

It was almost three and a half years after the declaration of war that the attacks on the SS Hare and SS Adela would occur. Of the thirty-six souls lost during that tragic Christmas season of 1917, seventeen of them came from the Dublin Dockland communities. This means that this period represents the single biggest loss of life locally during the Great War.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information, corrections, clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

While military control and restrictions remained in place for the duration, commerce continued, and for some local industrialists, business would be booming. In 1902, the Scottish born ship builder John Smellie was part of an endeavour to reinvigorate the industry here. He established the Dublin Dockyard Company and by the outbreak of war this had developed into a major local employer. A repair contract with the Royal Navy was signed as early as September 1914. They were soon producing pontoon bridges, floating targets to train gun crews, fitting ship gun platforms, depth charges, wireless cabins, mine laying appliances, telegraph poles, among other war related work. They would eventually be repairing torpedo damaged ships following U-boat attacks.

While military control and restrictions remained in place for the duration, commerce continued, and for some local industrialists, business would be booming. In 1902, the Scottish born ship builder John Smellie was part of an endeavour to reinvigorate the industry here. He established the Dublin Dockyard Company and by the outbreak of war this had developed into a major local employer. A repair contract with the Royal Navy was signed as early as September 1914. They were soon producing pontoon bridges, floating targets to train gun crews, fitting ship gun platforms, depth charges, wireless cabins, mine laying appliances, telegraph poles, among other war related work. They would eventually be repairing torpedo damaged ships following U-boat attacks.