From the Easter Rising to Bloody Sunday and Civil War

On Easter Monday 1916 amongst those who set out to ‘Break the chains with England’ was 14 year old Christy Crothers of the Irish Citizen Army. His Rising would be short lived, as on Tuesday afternoon, due to his young age he was ordered home. His role in the Independence struggle did not end here. He would go on to become a prolific intelligence gatherer for the Republican movement, and claimed responsibility for setting in motion events that culminated in the ‘Bloody Sunday’ attacks against British Military Intelligence across the City in 1920. (The names of many of those involved in the operation that morning are well known. Michael Collins ‘Squad’ is now legendary, and participants like Vinnie Byrne, Frank Teeling and Tom Ennis have all had their stories told. The role of Christy Crothers is being highlighted here for the first time).

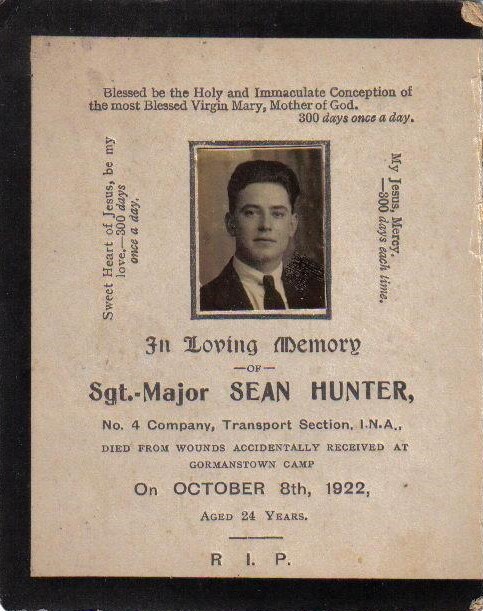

While Christy was a willing participant in the events of Easter Week and marched off to his engagement, for others the fight would come to them. This included Christy’s wife-to-be. The Hunter family of 14 Irvine Terrace are not believed to have been politically active up to this time. The area of the North Docks where they lived was occupied by the British Army, which under the pressure of sniper fire would turn on the local community. Christina ‘Dina’ Hunter, then aged 15, would afterwards join the Citizen Army while her older brother Sean Hunter would also become militarily involved.

This is the story of Christy and Dina Crothers of the Irish Citizen Army, a family at war with an empire.

“Boyhoods fire…”

Christopher Crothers was born in 1901, the son of James and Mary Crothers. His Father was a carpenter, his Mother a house-keeper. At the time of his birth the family were living at Ellis Quay, a two room dwelling on the North side of the Liffey. By 1911 the family were living in the South Dock area of the City, at Eblana Villas. Their fortune had seemingly improved, as even though Christy had been joined by three siblings (Cathleen, John and Josephine) they were now residing in four rooms.

According to family lore his father James had undertaken some work on the interiors of the Titanic. Due to time constraints he was unsatisfied with the quality of his workmanship and hoped to ‘complete’ it once the ship returned from its maiden voyage.

In 1913 the Great Lockout occurred in Dublin, an all out class war between the workers and the employers of the Capital. The savagery of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (D.M.P.) against the workers led to the formation of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA).This was initially a workers defence force, but between the end of the lockout in 1914 and the Easter Rising of 1916 it would evolve into a revolutionary military body, particularly under the leadership of James Connolly. As a schoolboy Christy joined the Fianna and seems to have been part of a group who met for a time at a building in Aungiers Street which they shared with the ITGWU. This was known as the “Jacob’s Branch” run by Bob DeCoeur. When DeCoeur founded the Fintan Lalor Pipe Band in 1913 he recruited young Fianna musicians from this group as members, such as George Campbell, Ted Tuke, Michael Delaney, and Tom O’Donoghue. All would go on to join the ICA, (and like Christy, fight at Stephen’s Green during the rising). Christie was apparently a first class piper and passed this skill on to his daughter Philomena. DeCoeur would remain a lifelong mentor to Christie, however, as his route into the ICA was musical rather than socialist or trade union based there was always some tension between the younger men such as himself and the older strike veterans who formed the backbone of the Citizen Army. At the time of the Rising he was aged 14, a Lieutenant of the ICA Boys section, under the command of Walter Carpenter OC, formerly of Caledon Road, East Wall.

“Under which flag ?”

April 1916 would see the first steps taken on the road to the Rising with the raising of the harped flag over Liberty Hall .This account of that event is from “The History of the Irish Citizen Army” , by R.M.Fox (1943) :

“In front of the hall itself, the Citizen Army cleared a space and formed up on three sides of the square. Inside the square was the women’s section, the boy scouts corps under Captain W. Carpenter and the FintanLalor Pipe Band.

Captain C.Poole and a colour guard of 16 men escorted the colour bearer, Miss Mollie O’Reilly of the Womens Worker’s Union who was also a member of the Citizen Army. With her were three young girl dancers known as ‘The Liberty Trio’.

The flag was placed on a pile of drums in the centre of the square. Commandant James Connolly took up his position with Vice-Commandant Mallin on his left and Lieutenant Markievicz on his right. The colour bearer advanced from her escort, received the colours from the commandant and turned to face the colour guard. The buglers sounded the salute and the guard presented arms. From the centre of the square came the skirl of pipes, quickening the blood of the hearers and making them feel that, at last, the nation was on the march.

As the colour guard, escorting the colours, reached the entrance of the hall, the flag bearer, holding the colours across her breast, passed into the hall, up the stairway to the roof. More and more people had been streaming to the centre of the city as the ceremony proceeded. Except for the clear space in the centre, Beresford place was packed tight. So was Tara Street and Butt Bridge, and each side of the quays leading to Butt Bridge, and each side of the Quays leading to O’Connell Bridge was impassable. Thousands were unable to see the ceremony in the square but all eyes were fixed on the roof of the massive square building. At last the young colour bearer was seen on the parapet of the roof. She fastened the flag to the staff and, with a pull of the lanyard, the green flag, with the golden harp upon it, went fluttering to the top.

A member of the colour guard speaks of the intense hush over that great throng, just before the flag was hoisted. It seemed, he said, as if they were all wrapt in a great longing, as if they wished and dreamed and hoped but dare not believe. Then suddenly it happened. The flag billowed above their heads.”

From this day onwards there was a permanent group of Citizen Army based at Liberty Hall in preparation for the rebellion. Here they assembled munitions, made bombs and the Proclamation was printed. Christy was part of these preparations. For the three weeks from the 1st until the 22nd April he was engaged in military activity. According to his own account : “Madam Markievicz told me that the fight was coming off” and for the first week “ I was in the hall at night time … we collected ammunition from different centres around the town on a hand-cart” . He then became part of the permanent body based there: “I left home about two weeks before Easter, I took up duty in Liberty Hall and I was there permanently all the time until I went into the fighting in Easter Week. On Easter Sunday and Easter Monday morning I was carrying despatches for Padraig Pearse and I came back to the hall at about 11 or 12 o’clock.”

“…they want nothing less than a Republic”

At mid-day James Connolly and Padraig Pearse marched off to the G.P.O while other bodies of men and women set of for their respective garrisons. Christy was under the command of Michael Mallin and marched off to the South Side of the City. This body included Frank Robbins, Christy Poole, and Bob De Coeur. Also included was Christina Caffrey , who lived at Abercorn Road (a neighbour of Sean O’Casey, whose fascinating story will be the subject of a detailed article at a later date).

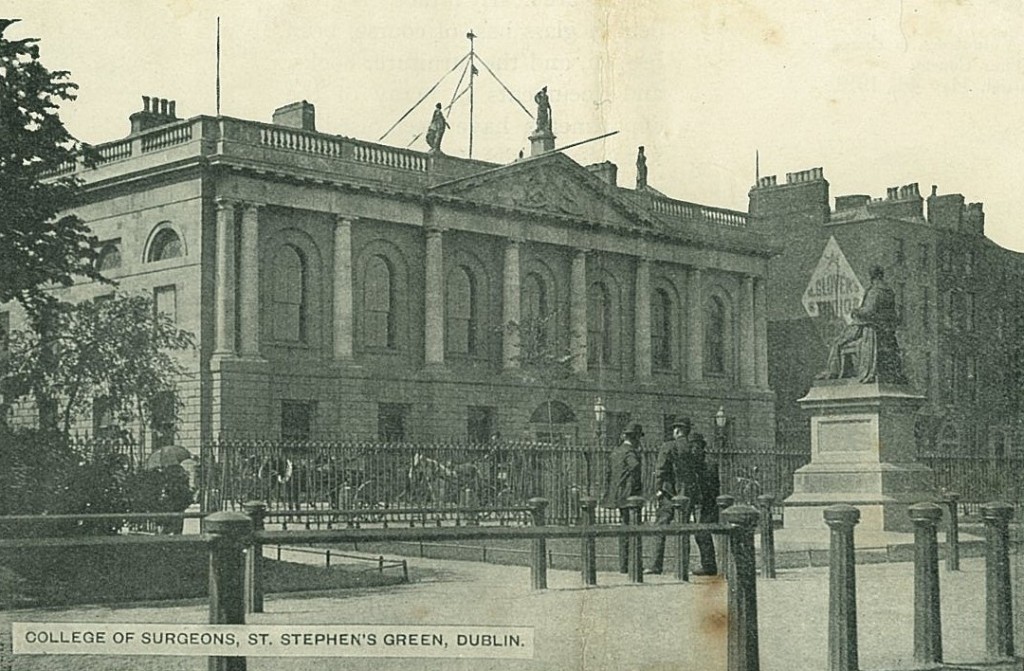

Michael Mallin was responsible for the Stephens Green garrison. The original plans for the insurrection had envisioned seizing the Green and the surrounding area and using the location as a supply depot and staging post for the surrounding garrisons. Commanding a central position in relation to a number of Garrisons (including Jacobs and Bolands Mill) and with a number of key roads connecting here this was a sound military ambition. It was expected to use 500 men to achieve this, but the countermanding order on Sunday resulted in a much smaller body of volunteers than expected and Mallin was presented with an impossible task in carrying this through effectively. One result of the lack of numbers was that buildings overlooking the park were not seized, and this would have fatal consequences. According to Frank Robbins: “The contributing factor which aided the military in this respect was, not as some people foolishly believe to be, lack of foresight on our part to recognise the importance of taking control of this building. The real problem which Commandant Mallin had to contend with was the scarcity of men to occupy all the positions set out in the plans.”

The plan had been sound and thorough – to ensure sufficient time for the seizing and fortification of St Stephens Green (and surrounding buildings) it was proposed that Harcourt Street Railway Station be taken over and that area barricaded to delay British Troops mobilised from Portobello Barracks. As the body of men and women reached the Green, a unit of 45 volunteers under Captain Richard MacCormack was dispatched to carry out this operation, and it was with these that Christy Crothers continued his marching.

As the body of men made their way along Harcourt Street an almost surreal encounter took place: “… the unit sighted a young British officer on horseback accompanied by his orderly, also on horseback. Tension mounted as the distance between the two groups narrowed and Volunteers released the safety catches of their weapons. McCormack ordered his men to remain calm, as any shooting at this early stage could jeopardise their mission and alert the authorities. As both groups drew abreast, Captain McCormack saluted the surprised British officer, who instinctively returned the salute. The pace quickened as the Irish Citizen Army group continued towards their destination. Glancing back, Captain McCormack saw the officer and his orderly gazing after the column suspiciously.”

The Railway Terminal Buildings were quickly seized .Passengers were marched out at gun point, and the men moved to set up barricades outside, seizing carts and automobiles to form their construction. An attempt was made to commandeer a tram (which would have made a formidable addition to the defences) but the driver spotted the group and managed to reverse and get away before his vehicle was taken, ignoring a volley of warning shots. Frank Robbins recalls: “We were furious at the loss of our potential barricade, but we could not but admire the crew’s adroit manoeuvre and their coolness in danger”. As the station was being occupied other volunteers also took up positions on the railway bridge over the Grand Canal and the South Circular Road. A smaller body of men (under the command of Joe Daly were ordered to occupy Davys Public House. Located at the junction of Richmond Street and Charlemont Mall this offered a vantage point covering both Portobello Bridge and Rathmines Barracks.

This group would have the second encounter of the day with the mounted officer and his orderly. Having become increasingly suspicious, they now rode back towards this smaller group: “Daly ordered his men to fix bayonets and spread out on the road and prepare to receive a mounted attack. With discipline and military precision, the men took up positions to receive the attack. The officer spurred his mount towards the Irish formation. A shot rang out, narrowly missing the cavalryman, who reined in his horse, turned sharply and galloped away”.

Arriving at Davys Public house there was another surreal, somewhat comical scene. The door was kicked open by James Joyce, who was employed there (and had last worked there on Thursday). The owner was behind the bar, and shouted to him “I’m giving you a week’s notice Joyce”, to which the reply was “I’m giving you five minutes Mister Davy” and a volley of shots fired into the counter. Mister Davy and his customers were bundled out of the building and the volunteers began securing their position.

According to the local history website,Rebelcharlo:

“Not long after fortifying and barricading themselves in, a Constable Myles of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) happened upon the bridge and was immediately shot at, wounding him in the left wrist.

It wasn’t long before the British Forces were dispatched from Portobello barracks to dislodge the ICA men. Snaking their way up the canal, they set up a machine gun near the La Touché/Portobello Bridge and peppered the place with bullets.

Only after a few hours of spraying the building did the call ring out to cease fire, discovering there was no returning fire from within Davy’s pub; the Irish resistance fighters had long since made their escape.”

Christy recalls his active service during this early part of the day as “taking and defending posts…erecting barricades” and specifically of “taking of Harcourt Street Station, covering retreat from Davies Public House”. Eventually all the units, from Davys and Harcourt Street withdrew to Stephens Green, where the duties of trench digging, fortification and requisitioning supplies continued. However, as Christy recalled: “During the Monday night the British got into the Shelbourne and the commercial club with machine guns and opened them on us. A few of our fellows were killed on Tuesday morning.”

This account is taken from the recently published “When the Clock Struck in 1916: Close-Quarter Combat in the Easter Rising” by Derek Molyneux and Darren Kelly:

“By 3.30 a.m. on Tuesday, Elliotson’s machine gun had been hauled up to the fourth floor of the Shelbourne. Its crew peered cautiously out of the window, and in the half-light saw the rebels still at work on the barricade. Each window facing the park and Kildare Street, of which there were approximately 60, was manned by one or two riflemen. By 3.50 a.m., the entire front of the Shelbourne Hotel bristled with weapons and the Vickers machine gun stood at the ready…The machine gun erupted into life. Strobes of blinding flashes emanated from the facade of the hotel as the trenches in the park were hosed with bullets from both the Vickers and the rapidly firing rifles. The cacophony echoed around the buildings surrounding the park, amplified by the cold early morning darkness.”

In “Shootout – The Battle for St Stephens Green, 1916″ Paul O’Brien describes how:

“The Irish Citizen Army was out in the open, and pinned down by soldiers who now had every battlefield advantage… Within the park, the first indication of the presence of British troops was the burst of machine-gun fire that ripped through the overhanging trees and thudded into the ground. Taken by surprise, the call ‘stand to ‘was shouted throughout the park. Men and women grabbed their weapons as bullets whizzed through the air while they sought whatever cover was at hand. Men threw themselves onto the ground in the firing position, making their bodies as small a target as possible. A ragged fire was opened up on the hotel, but all this seemed to do was attract the attention of the machine gunners, who swivelled his weapon to where the firing had come from…The intensity of the machine-gun fire pinned down many of the men in the park, leaving them with a feeling that they were in a death -trap. All they could do was lie under a rain of fire.”

(One of the first to die was James Corcoran. Originally from Wexford, he worked as a labourer on the Docks and had lived at a variety of addresses in Oriel Street /Seville place. The story of Corcoran will be covered in detail during the coming weeks)

The situation would deteoriate throughout the day, with the British elevated positions making it impossible to hold the Green. On Monday some volunteers had entered and held the nearby College of Surgeons and the entire garrison would be withdrawn to here. The previous military experience of men like Christy Poole was invaluable in achieving this with a minimum of casualties. This garrison would be held until the surrender on Saturday, but Christy Crothers would no longer be here.

“At about 1 o’clock on Tuesday Madam Markievicz came to me and told me she wanted all the boys. I went around and the only boys I came upon were Paddy Butler and Mick Dwyer and I brought them over and Madam instructed us to leave the post and go home as it was too dangerous, we were so young.” Christy left the garrison and returned home as ordered, avoiding injury, death or capture.

(Michael Dwyer, from Buckingham Street, and Paddy Buttner would both continue their activity in the independence struggle, eventually taking differing sides in the Civil War.)

“A lot of the boys got together…”

Immediately following the Rising hundreds of prisoners were deported to gaols in England and ultimately the Frongoch internment camp. The execution of the leaders created a public opinion backlash, and by Christmas of the year most of the prisoners had been released and returned to Ireland. Christy maintained his activities during this period, dedicated to keeping the movement operational:

“A lot of the boys got together, principally the ones who were officers and we decided that we would keep going until the men got out of jail. I was detailed for the south side of the city.”

During this period, and continuing through the years afterwards the procuring of weapons became a key activity of the movement. Christy devoted a lot of his energy to this pursuit, and seems to have grown almost obsessive about this role. Even before the prisoners were home re-arming was taking place, and in November:

“Information was given to me by one of my own lads that there were rifles in a hall in Lr.Pembroke Street. I went up to the hall and after a few weeks I got in and discovered I was in Carsons Volunteers Hall. I got a few of the lads together and two others I could depend on. There were 45 rifles in the place. The majority of them were old mausers and when we got the lie of the place, three of us raided it and got nine rifles.” The home of one of the group, Thomas Dunne, was raided and three rifles recovered. Christy “collected the rest of the rifles and took them over to North Frederick Street, as there was a company of volunteers starting there”.

Other examples recalled by Christy were an occasion when an ex-army officer at Percy Place was relieved of “Two revolvers and some few rounds of miscellaneous ammunition and a few swords”, while on another occasion he “raided the house of another army officer down around Pearse Street. We got only one revolver there”. In 1917 he was part of a group that raided Portobello Barracks to acquire rifles.

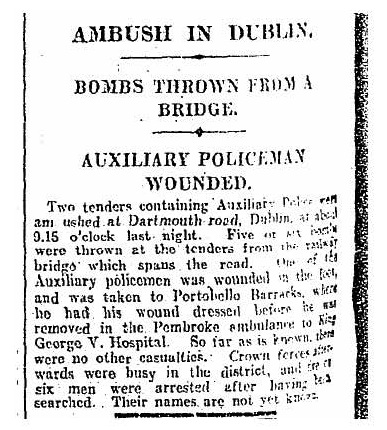

His commitment to securing weapons reached an extreme level during the Tan war, when in 1921 he held up his own boss to retrieve weapons. Christy was an apprentice at Harvey & McLoughlins and the premises was used to stage an ambush on Auxillaries. It had been noted that two tenders of troops passed each evening travelling from Rathmines to Beggars Bush Barracks. A total of 16 volunteers were in two positions to attack, including on the roof of Christy’sworkplace, but on the night in question the troops did not arrive as expected. After waiting for an hour they were preparing to withdraw when the tenders finally arrived and a dozen grenades, shotgun and revolver fire was launched against them. It was believed that four auxillaries were killed, while two volunteers were captured – following the chaotic ambush substantial munitions had been dumped here (“an amount of stuff-rifles, revolvers and bombs”) and were seized by the police. Along with a number of other men, including future brother-in-law Sean Hunter, Christy arrived at the yard where “We went up and held up the police, seized a motorcar belonging to the firm, put all the rifles, grenades etc on it, and took them away”. According to James O’Neill (commander of the Citizen Army after the death of James Connolly) : “They got all the stuff; Crothers ‘stuck up’ his own manager and got away with the stuff. He came down to me immediately it was over and I told him not to go back to work. The result was that he was more or less on whole-time duty then.” He later added “When the truce came on we made arrangements to get him back to finish his apprenticeship, which he did”.

(An unsigned note recording operations he participated in during this period includes reference to “London Bridge Job”, which was an ambush at Bath Avenue, possibly an attack on a Dublin Castle based agent, but further details of his involvement are not listed).

“Common robbers” on Sheriff Street

As Guerrilla warfare raged across the city, both republican and crown forces struggled to gain the upper hand. A curfew was introduced, and ‘normal’ policing was all but abandoned. To address this, (and also as part of the creation of a dual power structure) a Republican Police was established. However, as Padraig Yeates has pointed out, this “merely formalised the situation in large areas of Dublin. Not alone the Irish Volunteers but members of the Citizen Army, such as Larry McLoughlin, had been policing their localities for months. McLoughlin was a big, gruff docker, a veteran of the 1913 Lockout and the 1916 Rising whose beat included the docks, North Wall and the neighbouring community of East Wall.” (From ‘A CITY IN TURMOIL: Dublin 1919-21’).

Christy recalled an occasion when

“…there was a shop in Sheriff Street held up one Saturday night and all the money taken- I succeeded in securing the arrest of the fellows. They were common robbers. They were tried by the Army Council and told to leave the country”.

Christy would also later on take exception to the behaviour of some Citizen Army men, and claimed he spearheaded a re-organisation in the early 1920’s– “ Before the dump arms I had discovered that a certain officer and certain men had disgraced it’s name by highway robbery. When the other officers came out of jail this thing became information generally, as a result the citizen army ceased to exist under the officers who were in existence at the time this thing happened. I then approached the officers that I knew and they gave me sanction to carry on. I carried on. I re-organised the Citizen Army and I became the commandant. That was after the ceasefire order.”

In the shadow of St Barnabas

Christina ‘Dina’ Hunter was born in 1901. At the time the Hunter family were living in a one room tenement at number 7 McGuinness Court. Her father was a coach painter, while her mother, Sarah was a house keeper. They already had a two year old son John. They would later move to number 25 Townsend Street, another one room tenement, and the family would expand to include Sarah, Liziebeth and Jane Frances. The family would soon move North of the Liffey to 14 Irvine Terrace, and in time would continue to grow in number with Annie, Patrick and Edward arriving in subsequent years. A number of the younger children would attend the Wharf School (which is now St Josephs Co-ed on the East Wall Road). Her father now had a business based in the locality: “…his workshop was in a coach-house at the end of one of the big houses in Seville place.” Young Johnny would follow in the family tradition, but not working with his father: “Johnny was apprenticed to a coach builder because you never took on your own son”

It was at Irvine Terrace the family were living in 1916. During the rising the British military set up camp in St Barnabas Church (Upper Sheriff Street) , which overlooked Irvine Terrace and the small enclave of surrounding streets. In his autobiography “Drums under the Window” Sean O’Casey recalls how on Wednesday of Easter Week:

“all the lusty men of the locality were marshalled, about a hundred of them… and were marched under guard (anyone trying to bolt was to be shot dead) down a desolate road to a great granary. Into the dreary building they filed, one by one; up a long flight of dark stone steps, to a narrow doorway, where each, as he came forward, was told to jump through into the darkness and take a chance of what was at the bottom”. Johnny was amongst those caught up in this sweep, and the family recall: “he was pulled in by the British and they were all put in sheds down along the quays, and that’s how he got involved in the movement.”

During this period the women and children of the area were interned within St Barnabas Church. A number of civilian casualties also occurred in the vicinity, and O’Casey himself and his mother had narrowly avoided death when the British opened fire on their house from the bell tower of the church on Tuesday. It is most likely these events (and possibly the large numbers of labour and republican activists in the area) that encouraged brother and sister into the movement. By the next year Johnny would be in the Irish Republican Army. (See the story of Sean ‘Johnny’ Hunter here – http://eastwallforall.ie/?p=2542 )

‘Win the women to your cause and your cause is secure.’

Dina joined the Irish Citizen Army in 1917. She immediately began receiving training in first aid under Kathleen Lynn and instruction in small arms. Her first activity is listed as “Easter Monday 1917 fight with police at Tallaght”. Later in the year she was in attendance at the funeral of Thomas Ashe. During the rising Ashe had led the volunteers in Ashbourne Co. Meath, successfully capturing police barracks and seizing weapons and ammunition. He was sentenced to death for his role, but this was commuted and he was released in the summer of 1917. However, two months later he was back in jail for making “speeches calculated to cause disaffection”. In Mountjoy he went on Hunger strike to demand ‘political status’ and died here following brutal force feeding. His funeral to Glasnevin attracted 30,000 people and was a major show of strength for the republican movement. The Citizen Army was mobilised and significantly the firing party at his graveside included both ICA and volunteers. (Amongst the firing party was John Whelan, who would afterwards live at Seaview Avenue, East Wall for 25 years).

Continuing through 1918 and into 1919 Dina’s small arms training continues, and her medical proficiency progresses to “field ambulance work”. She also specifies that on November 11th 1919 she was “acting under orders of Commandant on protection of headquarters, such as scouting”. This was Armistice night, which commemorated the end of the First World War and was seen as an opportunity for British servicemen and other loyalists to attack republican and nationalist targets, with Liberty Hall successfully defended a year earlier.

By 1920 she is “Carrying messages in connection with work of intelligence branch” and lists her active service for 1921 as “Assisting intelligence officer”. The intelligence officer in question was Christy Crothers. Christina and Christy would marry in October 1922. (Tragically, the death of her brother Sean would occur within days of this happy occasion).

“…responsible for the destroying of the British Intelligence staff in Dublin”

From late 1918 onwards Christy became largely devoted to intelligence work, and it was in this regard that he could claim his greatest success. According to James O’Neill Crothers had “produced some valuable information which was responsible for the destroying of the British Intelligence staff in Dublin”, and claimed “he had a peculiar connection and seemed to be able to find out these things”.

It is here that the story of Christy Crothers really takes an extraordinary turn. He built up his own intelligence connections, gathered information on British agents in the city which ultimately reached Michael Collins. Christy (and others) claim that the Bloody Sunday operation was based on his work. When interviewed in 1935 in relation to this Crothers was asked “You make the claim you really supplied a substantial amount of information in connection with ‘Bloody Sunday?”He replied “I claim all the information.”

Certainly, the chain of events which culminated in the co-ordinated attacks on that morning began with Christy. During the interview referred to above , Christy outlined in some detail his intelligence work, his network of contacts and the chain of command through which his information passed –

“My whole work was in getting together a proper intelligence. I was sort of free lance.” He later added “I was the only recognised Intelligence officer for the Citizen Army.”Christy initially passed all the intelligence gathered to Bob De Couer, now secretary of the ICA Army Council (living at 48 Sheriff Street). There was a working relationship between the ICA and IRA at this time, and the information was further passed on to Barney McMahon, who was directly in touch with Michael Collins.

“I secured a small number of agents who were connected with the British here. One of them was a woman named Kate Murphy, the other a man named Thomas Millea.” Murphy was “a personal friend of Mrs Sankey. Mrs Sankey’s house was, at that time, a call office for the British Intelligence here. Kate Murphy worked for her. She eventually succeeded in putting me on to the people who were shot on ‘bloody’ Sunday”. The house was 15 Upper Fitzwilliam Street. “I used to visit the house in Fitzwilliam Street once or twice a day. Any documents I could get I took and handed them over. When they left that house they scattered and it was then that the group of people were of assistance to me. Millea was in a house in Mount Street and a British intelligence officer named Bennet went to stay there.”

George Bennett was shot dead at 38 Mount Street on Bloody Sunday, alongside another agent Peter Ames. Michael Collins believed that Bennett and Ames were the leaders of the now notorious Cairo Gang, the core of British Intelligence operations based in Dublin.

“…able to find out these things”.

Christy elsewhere explains in greater detail how he operated against the agents, in particular discovering and tracking the group led by George Bennett, assisted by Kate Murphy, a friend of his Grandmother:

“Miss Murphy approached me one evening when she was visiting the house and told me that about twelve men had taken up residence in the house where she was employed. She thought that they were ex-British Officers … she told me that while these men were supposed to be commercial travellers they never went out in the daytime; that the earliest they left the house was at 5 o’clock in the evening and that they were not back when she was retiring. She added that she knew they returned in the small hours of the morning – sometimes around 6 and 7 a.m. They were never seen leaving together: they generally left in ones and twos and on some occasions they did not leave the house until very late at night. All these matters I reported to Captain de Coeur…. As a result of this I was asked to try if possible to get the name of every man who was in the house and if possible to report more regularly on what was occurring there. This I did. As well as that I visited the house whenever the opportunity occurred and searched for any documents or evidence that would be of help. A few weeks later I was instructed to keep away from the house but at the same time to keep in close contact with Miss Murphy. About the month of August Miss Murphy reported that the men were leaving the house in the matter of a few days. I asked her from whom did she get that information. She told me that Captain Bennett told her they were going. I then asked her how did it occur that he spoke to her and gave her this information and she told me that she had occasion to go into his room that morning and he started to jeer her about her friends and told her that he was leaving and that her friends would find it very hard to find him. I reported this matter at once and was told to carry on. It would appear from the information I received that somebody was observed watching the house and that they in turn were watched. The men in question left the house in about three days. It was impossible to learn where they went because it was understood that they were breaking up in ones and twos.”

However, it is clear that Crothers and a number of IRA intelligence officers utilised other resources to continue tracking the men, with deadly outcome on ‘Bloody Sunday’ November 20th. As stated, Thomas Millea would provide the information to Crothers on Bennett’s new location at Mount Street. In fact, both Bennett and Ames had been living at 28 Pembroke Street until Saturday, the details of their departure passed on by a maid there. On the morning of the IRA operation, two Intelligence agents were shot dead at the house in Pembroke Street, while four other British military operatives were injured. Their sudden change of address meant that a group was hastily assembled to target Bennett and Ames. This group included Vinnie Byrne, Tom Ennis and Tom Duffy. A maid, Katherine Farrell answered the front door and pointed out the two rooms of the men, who were still in bed. Bennett had tried to grab a revolver from under his pillow but was not quick enough. He was taken into Ames room where both were shot dead.

The impact of these shootings on the British Intelligence operation was deliberately played down for propaganda purposes, but as one of Collins men stated – “The effect was paralysing. It can be said that the enemy never recovered from the blow.”

While Christy Crothers was only one of a number of republican intelligence operatives active at this time, his work in targeting Bennett and the other agents was central to the whole ‘Bloody Sunday’ operation. Up to this point he had been reporting to Bob De Coeur and James O’Neill, but after this coup he was introduced to Michael Collins. “He sent a man by the name of Paddy Kennedy to me, and Paddy Kennedy kept in touch with me”.

(Kennedy had joined the Citizen Army in 1917, and later transferred to the 2nd Battalion Irish Republican Army. In 1920, at Oriel Hall (just off Sheriff Street) he was selected for GHQ Intelligence Staff, and would serve under Director of Intelligence Michael Collins. He was a trusted operator, and played a role in ‘Bloody Sunday’ and related events - the rescue of Frank Teeling from Kilmainham Gaol and the shooting of the informer John Ryan in the Monto).

Christy continued his activity, reporting to Kennedy until the truce. “I was working on the people who took over after Bloody Sunday- Dunne, and Major Trimm and Captain Stotts – they sometimes lived in Sydney Lodge. The Truce intervened. I was working on other things – individual targets. One of them was afterwards shot”.

Black propaganda and dirty tricks

While investigating Bennett and the group at Fitzwilliam Street, Christy uncovered evidence of the black propaganda operations they were engaged in:

“Sometime between the months of May and June one morning the citizens of Dublin found posted on most of the tram and lamp standards in the city a small bill-head purporting to have been issued by the Catholic Bishops with reference to association with the I.R.A., Sinn Fein and kindred organisations. That evening Miss Murphy came to me with three or four of the posters and informed me that the men staying in the house had hundreds of these posters and that they were out all night posting them up throughout the city. She came to me at roughly 7.30 p.m. and I asked her if I went with her could I get into the house. She said yes, but that it would be a bit risky, adding that these men had gone out but she did not know whether they would return or not… on top of a wardrobe in the front drawing-room there were actually thousands of the bill-heads.” Christy reported immediately to Bob DeCoeur who passed details on to the Intelligence section of the Dublin Brigade. “As a result of this I was asked to try if possible to get the name of every man who was in the house and if possible to report more regularly on what was occurring there. This I did. As well as that I visited the house whenever the opportunity occurred and searched for any documents or evidence that would be of help.”

Around this time a handbill was distributed advising ‘self-respecting Irishmen’ on how to safely inform (by post) on the I.R.A. It included advice “to give neither your name nor your address. Remember also to disguise your handwriting, or else to print the words”. The letters were to be addressed to D.W.ROSS, Poste Restante, and G.P.O. London. It also offered informants the option of at a later date identifying their anonymous letter and claiming a reward.

According to James O’Neill: “…and in connection with the Ross Handbills, we discovered these before they were distributed. We got this information also from DeCoeur.”

This suggests that Bennett and co. were also responsible for this operation, with Christy discovering the details and passing them on through the usual channel.

“The truce intervened…”

The ‘Tan war ended in July 1921.Protracted negotiations led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty early in 1922, which split the republican movement. Both Christy and Dina took the anti treaty side, while Sean Hunter joined the National Army. The Crothers were active participants in the ‘Battle of Dublin’ which erupted in June of 1922, signalling the eruption of a full scale Civil War across the country. Earlier, in April anti treaty republicans had occupied the Four Courts, with approximately 200 men. A tense stand-off with Free State forces continued .Despite efforts to defuse the situation, and a reluctance to engage in armed actions, attitudes hardened on both sides and after an ultimatum to surrender the building was ignored a bombardment of the fortified courts began on June 28th.

Christy had been continuing his intelligence gathering up to this time, passing the information on generally to Bob DeCoeur and also to John Hanratty (another of the original Citizen Army recruits). He visited the republican Headquarters at Barrys Hotel and was sent to the garrison at the Four Courts to personally pass on a warning to those inside:

“I got information the evening previous that the four courts was to be attacked. I took it up to the four courts – I had a permanent pass to get in. I handed the Information over to Plunkett and Russell.” He was not present during the attack.

Once the bombardment began, fighting spread to the O’Connell Street area. The anti-treaty forces under Oscar Traynor occupied adjoining buildings at the North East end of the street – breaking through the walls of The Gresham Hotel, the Crown, the Granville and the Hamman hotel to create a fortified ‘block’. Tom Ennis commanded the Free State forces who responded here and fierce fighting continued for a number of days.

Christy and Dina were both involved in the activities here.

Christy took part in the fighting at Barrys Hotel and the general O’Connell street area, but we have seen no detailed record of his combat. He does say “I did not stop until we got the order to evacuate; that was the general evacuation of the Hamman hotel”.

According to Eilish Lynch, daughter of Christy and Dina, her mother was with Cathal Brugha up until his death. As the buildings of ‘the block ‘they had occupied were now in flames, and they were clearly surrounded and outgunned by the opposing forces, the order to surrender was given. Having watched his comrades leaving in defeat, he deliberately ran towards the Free State troops wielding two revolvers and was shot down. He died two days later in the Mater hospital.

Christy continued his intelligence gathering activities throughout the duration of the civil war, which ended in April of 1923.

“Peace after the final battle”

In terms of military activity the direct involvement of Christy and Dina may have ended with the ceasefire and dump arms order of 1923, but for Christy his involvement with the Irish Citizen Army and fellow members would continue for many years. He would become part of the Old Irish Citizen Army Comrades Association, which provided invaluable in assisting members to secure the military pensions due to them. However, in the aftermath of the Civil War the most immediate problem facing Christy Crothers was that having lost his job he had been unable to finish his apprenticeship as a carpenter. Bob DeCoeur came to his rescue eventually getting him a placement with the Office of Public Works at Schoolhouse Lane. Christy finished his apprenticeship in October 1922. As a fully fledged Carpenter he could now marry Dina Hunter which took place on the 1st November that year. Nine days later he received his union card for the no.1 section of the No. 2 Branch of the Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers. Over the next decade he would rise through the ranks to Overseer and Chief Carpenter in 1933.

Old Comrades

The rise of Fianna Fail to power in 1932 saw the extension of the Military Service Pension to include 1916 and War of Independence veterans who hadn’t joined the Free State Army during the Civil War or been killed in action during the War of Independence. Because of the unique position of the Irish Citizen Army outside the mainstream of the Irish Volunteers or IRA, the pension assessment board had real difficulty in assessing applications from former ICA members. The fact that many were also closely associated with the re-emerging Irish Communist Party didn’t help matters either. ICA veterans John Hanratty, Seamus McGowan, and Dick McCormack had reorganised around former IRA Chief of Training Mick Price. They had a drill hall located at Commons Street in the North Wall. Other former ICA members, such as John O’Keeffe, were active in the Irish Branch of the Unemployed Workers Movement which had been founded by the British Communist Party. Therefore there was a degree of suspicion by the authorities in dealing with ICA applications. At the same time former ICA members were reluctant to say anything which might affect the outcome of their case.

Bob DeCoeur had presented Christie with the remaining ICA records before he died and Crothers quickly became one of the main sources used by the board to verify the service of ICA applicants. Reading his reports today can give a very misleading sense of Christie Crothers. In many cases he dismisses claims by applicants, even when they have been backed up by other veterans. Some can almost appear as being vindictive –possibly a type of payback for all the years when the more labour orientated members tormented him for his lack of a socialist background. Eamonn Carpenter (son of ICA veteran Peter Carpenter, formerly of Caladon Road) knew Christy well. Christy had gotten him a start with the Office of Public Works at schoolhouse lane and had taken him under his wing while there. Eamonn recalls him as being “as straight as a line and he didn’t deviate”, claiming “if Christy Crothers wasn’t sure of something he would never sign his name to the paper.” Careful reading of those applications shows the great lengths Crothers went to in many cases to verify statements being made by applicants. But as Eamonn Carpenter recalls “if he wasn’t satisfied he refused to sign off on it.”

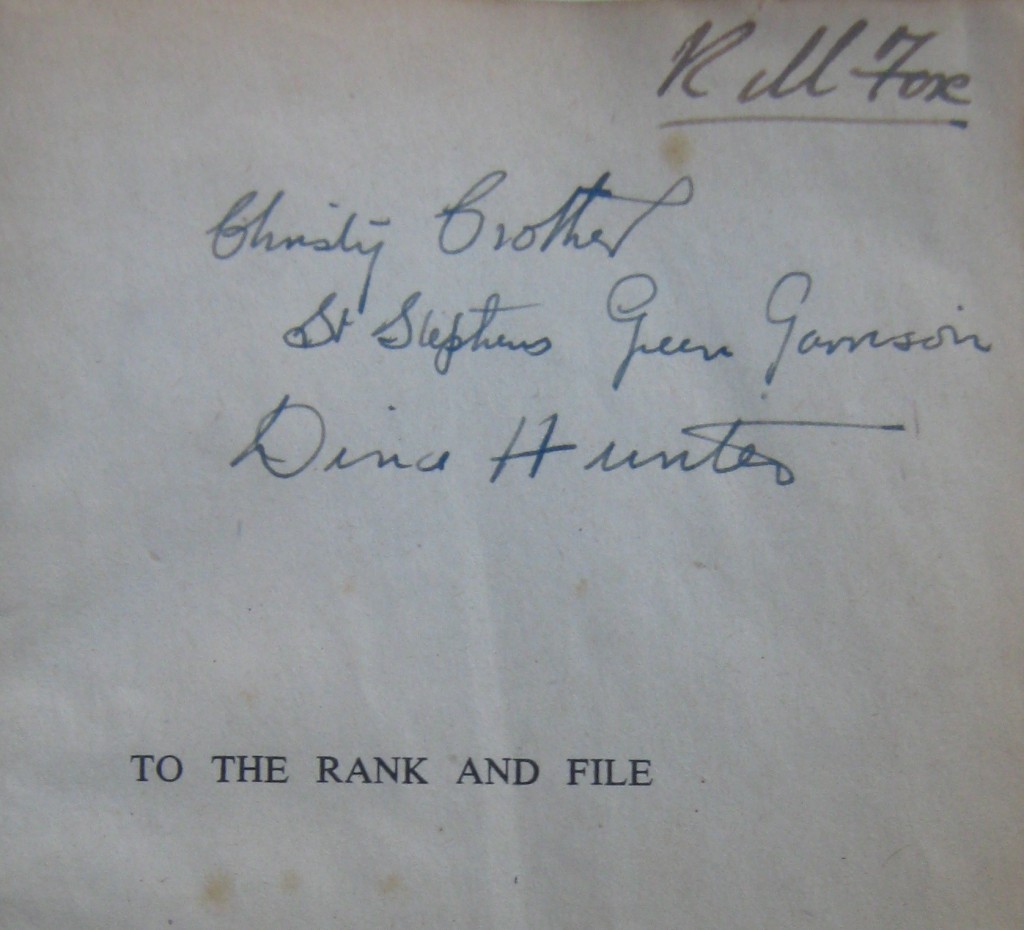

In order to assist former ICA members in applying for their pensions and to create a lasting record of their achievements an Old Irish Citizen Army Comrades Association had been founded in 1936. They lobbied for jobs and houses for members, many being provided by the philanthropic efforts of Kathleen Lynn and former ICA Commandant James O’Neill, then a successful builder. By 1938 over 86% of survivors were members of the Association but by the 1940s numbers were dwindling. Christy Crothers was the association’s last secretary and his final published notice has a note of sadness as he appealed for any survivors to get in touch. Dwindling numbers had seen many of the veteran groups merge, however, the ICA maintained their independence in all commemorations, with Crothers, Paddy Buttner, and Stephen Murphy regularly providing firing parties at old comrade funerals and other events associated with the revolutionary era. (The Association also commissioned and oversaw the publication of “The History of the Irish Citizen Army” by RM Fox in 1943).

From ‘the emergency’ to ‘the troubles’

In 1942 Christy was abruptly dismissed from his OPW Job at Schoolhouse Lane. He appealed to the Labour Party who investigated his case and found that a number of Veterans working in the public service had similar experiences and had been replaced by Fianna Fail party members. In 1941 Fianna Fail had attempted to bring in a new Trade Union bill which they claimed would bring “foreign” unions into line. Labour opposed the bill, knowing that particularly within the building trade ,the likelihood of unemployment meant that workers would have to either temporarily migrate if not permanently emigrate in order to seek work (it was estimated that 1800 Carpenters were unemployed at that time). The Amalgamated Woodworkers had branches throughout Britain and in the USA and Australia. This meant that Irish Workers had little trouble having their cards recognised when they emigrated looking for work. The Old Citizen Army Association had passed a resolution condemning the bill in July 1941. Things came to a head in Cork when members of the Amalgamated Woodworkers refused to work with members of the new Irish Union of Woodworkers. In the end Labour won the day and Christy Crothers got his job back. Interestingly, he joined Fianna Fail shortly afterwards.

Crothers had been a teetotaller all his life having joined the Temperance Charity the Third Order of St Francis as a young man. During the aftermath of the 2nd World War, like many other former Citizen Army members he was involved in Operation Shamrock. This was an attempt by the Irish Red Cross to resettle over 1000 German children in Ireland between 1945-6. The Crothers took a young German girl named Clara into their home in Inchicore for several years as did their neighbour and fellow ICA veteran Peter Carpenter. In 1968 as trouble flared in the North of Ireland thousands of refugees fled south, many ending up in a refugee camp in Gormanston military barracks. Crothers was to the forefront in organising supplies of bedclothes, food, and other necessaries for the refugees. So successful were his efforts that it was stated that the camp was ‘another Butlins’. Other family members, such as his daughter Eilish and her husband Jerry also contributed to these endeavours. (The poignancy of the fact that Sean Hunter had died here almost half a century earlier was not lost on the family).

The 50th anniversary of the Rising , Christy with other Citizen Army veterans . He is second from right in back row . Rosie Hackett. is at front.

Ironically, given his role in Dublin in acquiring weapons during the independence struggle, Christy would in later years go into the business of owning and operating a gun shop in the city, first at Lombard Street and later at Grand Canal Street. Eamonn Carpenter recalls they were always upstairs, giving them an air of mystery. However as far as is known Christy was not politically active at this period and his business was completely legitimate.

Christy received a military service pension and was awarded a 1916 medal and (1917-1921) service medal. Dina was unsuccessful in her pension application (as many women were) but would later receive her (1917-1921) service medal. She also successfully applied for the posthumous awarding of a similar service medal for her brother Sean.

Christina ‘Dina’ Crother died in 1980.

Christopher ‘Christy’ Crother died in 1982.

Dedication from RM Fox to Christy and Dina on original edition of “The History of the Irish Citizen Army” (1943).

In compiling this feature material from the Bureau of Military History has been invaluable. The full story could not have been told without the co-operation of the Daughters of Christy and Dina – Eilish Lynch and Phil Churchill, and their cousin Elizabeth ‘Betty’ O’Brien (daughter of Annie Hunter) who kindly gave us their time and shared their family story. Discussions with Eamon Carpenter were invaluable and provided an important insight into the character of Christy.

(Images from various sources – Hunter and Crother photos provided by the family)

For corrections, clarifications or if you have further information please contact: eastwallhistory@gmail.com