“I see his blood upon the rose”

Sean Hunter, Bloody Sunday and his tragic death in 1922

The grave of Michael Collins in Glasnevin Cemetary is the most visited grave in Ireland. His grave is constantly adorned with flowers and other tributes, and is rarely without a group around it. The late historian Shane Mac Thomais recalled how every February 14th that valentine cards would be placed here. Surrounding Collins are the markers of many of the men who died in the tumultuous years that saw the birth of the Irish Free State. For most, the final resting spot of the Big Fellah is the main attraction here, and the names of most of the others are of little interest. However, they are not all anonymous and forgotten’ collateral’ of the birth of our nation, and almost a century later some of these are still remembered by their families and others. Cemetery staff had noticed that a single rose appeared on a particular marker every year, and had wondered about it’s significance.

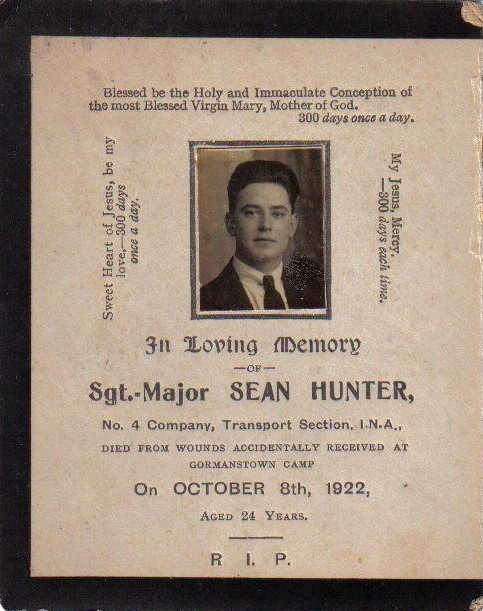

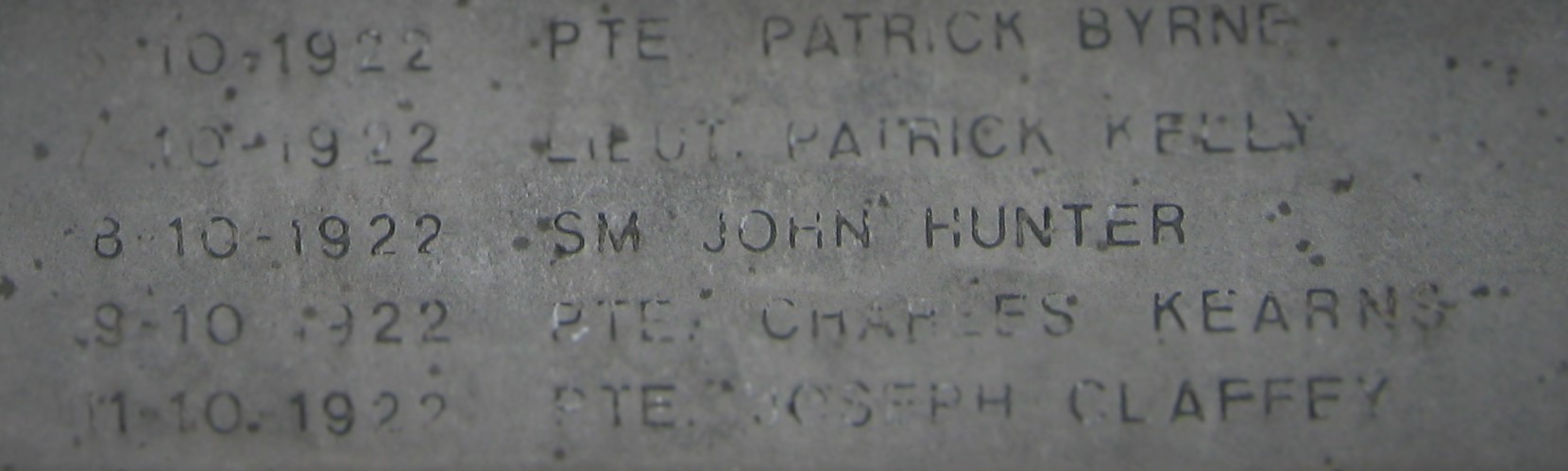

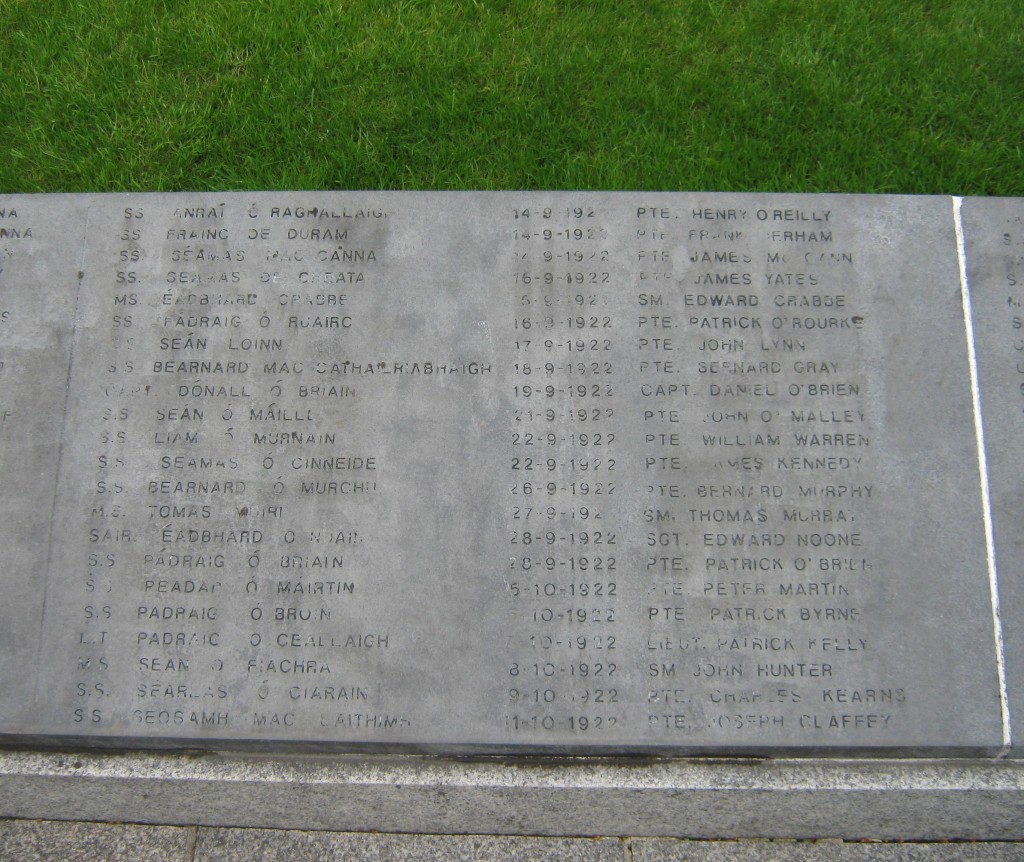

The rose is placed above the name of Sean (‘Johnny’) Hunter, and is put there by his niece, Eilish Lynch, fulfilling a promise she made to her mother shortly before her death. The request by Christina (Dina) Crothers (nee Hunter) that she “always remember Johnny” has been honoured each year since. Sgt Major Sean Hunter died on 8th October 1922, two days after being shot in the throat at Gormanstown Camp. Sean was a resident of the North Docks, living at 14 Irvine Terrace. Christened John Hunter, like many in the National movement at the time he adopted the Gaelic version of the name. His family members still refer to him as ‘Johnny’. He had been a volunteer in the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Republican Army. He participated in the ‘Bloody Sunday’ operation against the British spy network in 1920, and after the treaty signing joined the national army in 1922. At the time of his death a vicious Civil War was raging and Michael Collins was amongst the many already dead .Despite this, the fatal injury did not occur in an ambush or shoot-out with anti treaty republicans, but rather he died from a single shot fired by a fellow officer, Lieutenant Frank Teeling .Tragically, Frank Teeling was not just a fellow officer in the National Army, but was also a North Dock resident and was at that time the most famous participant in the Bloody Sunday operation.

This is the story of Sean Hunter, compiled by the East Wall History Group in conjunction with his nieces ,Eilish Lynch and Phil Churchill (Daughters of Christina Hunter) and Elizabeth ‘ Betty’ O’Brien (daughter of Annie Hunter ) .

A Coach builder in the Docks

The Hunter family had lived for a number of years south of the Liffey, in what was the Trinity Ward. According to the 1901 census they were residing in a one room tenement at number 7 McGuinness Court, with head of the household John Hunter listed as a coach painter, while his wife Sarah was a house keeper. John (Sean) was two years old and Christina was three months. By 1911 the family could be found at number25 Townsend Street, another one room tenement, and had expanded to include Sarah (aged 4), Liziebeth (aged 2) and Jane Frances (4 months).

The family would soon move to the North Dock and would reside at 14 Irvine Terrace (where a family member remained until very recently). What prompted their move across the river is not clear, but families were often very transient at this time, and they already had relations living at 5 Irvine Cottages, Church Road. The family would continue to grow in number, Annie, Patrick and Edward arriving in subsequent years. A number of the younger children would attend the Wharf School (which is now St Josephs Co-ed on the East Wall Road). According to family lore ,John had an involvement with two Coach Businesses, one at North Wall and one in Bournemouth in England.“His workshop was originally at the back of a house in Seville Place… That’s where his workshop was, in a coach-house at the end of one of the big houses in Seville place.”

Amongst the contracts to their credit it was claimed that they had painted the Queens own coach. It was recalled that an aunt “used to tell me about playing with the gold-leaf, they thought nothing about it, to them it was gold leaf, but it was expensive stuff to play with”. Sean would follow in the family tradition, but not working with his father, as Eilish explains: “Johnny was apprenticed to a coach builder because you never took on your own son”

There is no evidence that any of the family members had any interest or involvement with the political or social movements coming to prominence at this time. The future playwright Sean O’Casey lived quite close, in the same small enclave of streets bounded by the railway, and he was active in the trade union /socialist movement that were steadily growing at this time. In August 1914 the ‘Great War’ had begun and Europe was to be engulfed in bloody conflict and millions would lose their lives in the next four years. John (Snr) was forced to make a change in his plans for his family -“He was going to close up in Dublin and enlarge the place in Bournemouth but then he would have been conscripted into the British Army so he did the reverse – close the place in Bournemouth and enlarge the one in Dublin.” His caution was sensible, but his decision had unforeseen consequences for his family, particularly fatal in Sean’s case.

The 1916 Rising

“England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity” was an old Fenian saying. On Easter Monday 1916 an armed insurrection against British Rule was launched, and the Hunter family would be amongst the North Dock residents caught up in the events. According to Sean’s nieces, he became an innocent victim of the British army reaction to rebel activity in the area. He was returning from work when “he was pulled in by the British and they were all put in sheds down along the quays, and that’s how he got involved in the movement.”Their near neighbour Sean O’Casey recalled the events of Easter week 1916 in his autobiographical volume “Drums under the window”. His account is invaluable, describing the impact on the civilian population in North Wall, particularly those in the streets surrounding St Barnabas Church – including Abercorn Road where he lived and Irvine Terrace where the Hunters lived. He describes how the army turned the Church into a barracks, and how they interned the men of the community:

“The next evening, all the lusty men of the locality were marshalled, about a hundred of them, Sean joining in, and were marched under guard (anyone trying to bolt was to be shot dead) down a desolate road…” O’Casey also described how on Tuesday he and his mother narrowly avoided death when the British opened fire on their house. Separately, a young boy, 8 year old Walter Scott from nearby Irvine Crescent, died from a gunshot wound received, most likely fired by the British military.

As Eilish has said: “that’s how he got involved in the movement” .It is likely that his own experience at the hands of the military, the treatment of the community and personally knowing some of those who died or were imprisoned afterwards all contributed to Sean’s involvement with the republican movement. His father’s decision to remain with the family in Ireland likely spared himself and Sean from conscription to the British Army, but may have indirectly led to his involvement in the struggle for Irish National independence, military service of a different kind and his eventual violent death.

A family at war with the empire

By the following year Sean had joined the Irish Republican Army, and was a member of B Company, Third Battalion Dublin Brigade, in which he served until the truce of 1922. (He was not the only family member who would follow such a path. His sister Christina would join the Irish Citizen Army, and would receive medical training from Kathleen Lynn and later become involved in intelligence gathering. It was while engaged in these activities that she crossed paths with Christopher Crothers, a fellow Citizen Army volunteer who had taken part in the Easter Rising aged just 16 years old. They would eventually marry in 1922, and were the parents of Eilish and Phil. In a future article we tell more of the story of Christopher and Christina, and their fascinating role in the revolutionary period).

Sean Hunter died in 1922 and left no personal record of his military activity. In 1924 his mother applied under the Military Pensions Act for a Gratuity on the grounds that she was ‘Part dependent on the deceased’. A gratuity of £100 was granted. In 1942 his sister Christina applied (successfully) for his service medals to be issued to her, and her application necessitated sworn testimony from his commanding officers acknowledging his service. These state that he was an active member of B Company, Third Battalion Dublin Brigade and lists key engagements as (bloody Sunday , Brunswick Street ambush and Westland row). There are no detailed accounts of his exact role in any of these events, but as his involvement has been confirmed we will provide an overview of these actions, in chronological order.

“By their destruction the very air is made sweeter”

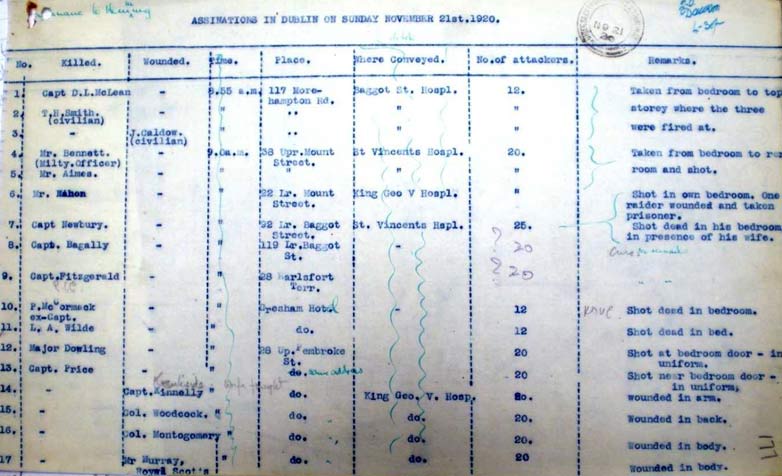

The events of ‘Bloody Sunday’, the 21st November 1920, are amongst the most iconic and best remembered from this conflict. In a series of co-ordinated actions at 9am that morning attacks were launched by the Irish Republican Army on the British intelligence network in the city, resulting in 14 deaths. That afternoon the notorious shootings by British forces at Croke Park during a Dublin / Tipperary match led to a further 14 fatalities, one player and 13 spectators. (And later that evening, in an atrocity often forgotten, three prisoners were shot dead in cold blood at Dublin Castle, with claims they tried to escape now largely dismissed).

Sean took part in the mobilisation that morning. The operation was carried out by The Squad (synonymous of course with Michael Collins) backed up by volunteers from the Dublin Brigade, Irish Republican Army. The British are believed to have had somewhere between 60 to 100 trained intelligence agents operating in Ireland at this time , and under the direction of Michael Collins and Cathal Brugha the plan was to target up to 30 of these for execution in a single operation . Some of those targeted were not where they were expected to be (including at an address on East Road, East Wall), but 19 men were shot including a number of auxiliaries, a soldier and an R.IC. Man. (14 died that day, one shortly afterwards from his wounds and four recovered).B Company, Dublin Brigade of which Sean was a volunteer took part in two operations, at numbers 92 and 119 Lower Baggot Street. Sean was attached to the third battalion, which has been identified specifically with the shooting of Captain Geoffrey Thomas Baggallay at the second address. An account of Baggallay’s death was given by Matty MacDonald, who along with future Taoiseach Sean Lemass, was one of those who shot him – “We knocked at the front door a maid came along. We have a letter from the Castle, will you deliver this note to Captain Baggallay, a one legged man. The maid pointing and in we went in. We tapped at the door, opened it and walked in. There were 3 of us. Baggallay was in bed. Lemass, Jimmy and I. I was kind of scared. ‘Captain Baggallay?’ ‘That’s my name.’ ‘I suppose you know what we came for. We came for you.’ …‘Get up.’ He was in pyjamas. Lemass and Jimmy and I fired, 2 in the head from the 3 guns. I heard maids screaming afterwards but I was told she was alright.” The captain was actually hit four times, on the top of the head, through the left eye and twice in the chest. The group retrieved a camera and papers from the room before leaving. An official Dublin Metropolitan Police report on the morning’s shootings records the figure of 20 as the number of attackers at this address (though interestingly this is hand written and includes a question mark). Sean or his role is not specifically mentioned in any record of these events, but aside from the men entering the building there would also have been sentries posted, look-outs and transport etc.

A shoot-out on Brunswick Street

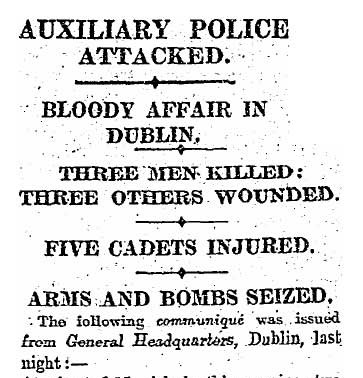

On the 14th March 1921 a major gun battle took place on Great Brunswick Street (now Pearse Street), that left seven dead. Two truckloads of auxiliaries accompanied by an armoured car arrived to carry out a raid and were fired upon with revolvers from a number of locations. They responded with a heavy machine gun and exchanges of fire continued for some time, while incredibly some hand to hand fighting also took place on the street. One newspaper report claimed that shooting took place intermittently from 8.15pm to 9.00am, with “sniping being maintained through the 7 hours”. The army also claimed that a number of casualties were removed from the area and blood trails smeared adjacent streets. While newspaper reports described this as an ‘ambush’ it seems likely that the raid on an ‘illegal assembly’ was resisted by an armed guard. The next day weapons, ammunition and bombs were found in number 144 Brunswick Street, and it obvious that an I.R.A meeting was taking place here. Again, there are no exact details of Sean’s involvement, though his participation was verified.

Gathering up the munitions

Another operation that Sean was engaged in is recalled by Christopher Crothers, his brother- in- law. Crothers was consistently engaged in intelligence gathering and weapon procurement during the entire period. – “There was one of my lads waiting … and he told me there had been an ambush and said there was an amount of stuff – rifles, revolvers and bombs left behind. I could do nothing as curfew was on but on the following morning I got out early and got to Dartmouth Road and went into McLoughlins yard and saw the stuff. I immediately went to ‘B’ Company, Third Battalion (my brother was a member there) and got two other volunteers. We went up and held up the police, seized a motorcar belonging to the firm, put all the rifles, grenades etc. on it, and took them away.” Sean was one of those who accompanied Crothers to retrieve the material.

“The only Johnny in the house…”

During this period Sean had become known to the authorities and 14 Irvine Terrace was targeted as attempts were made to capture him. According to Betty: “Mammy used to talk about the black and tans and when they used to raid the house, and take her father instead of Johnny because his name was John as well… he was arrested several times ,because they thought he was Johnny “. Eilish also recalled that during a raid her mother had sat at a sewing machine preventing family certificates being discovered, while “our grandfather said he was the only Johnny in the house so he was sent to Ballykinlar camp.”

While on the run he also used his cousin’s address at 5 Irvine Cottages, along with premises in Townsend Street. According to the family, a signal was arranged at Townsend Street – leaving a coat hanging on a chair – to let it be known if it was safe to enter.

“…after truce and treaty and the parting of the ways”

The ‘Tan war ended in July 1921.Protracted negotiations led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty early the next year , which split the republican movement and led to the outbreak of the civil war . Sean took the pro treaty side in the split and joined the National Army. To date we have seen no record of Sean’s military activity during this period. His sister and brother- in-law took the anti-treaty side, and both participated in the ‘Battle of Dublin’ which engulfed the City Centre at the end of June. Christina worked in an intelligence gathering and scouting capacity and also carried dispatches According to the family she was in the company of Cathal Brugha at the time of his death. Christopher continued his intelligence gathering for republican forces and took part in the fighting at Barrys Hotel and O’Connell Street. In response to a query on a pension application in 1935 whether she had served in the national army she emphatically answered in the negative “No, I did not agree with the Government in office”. Despite the savage nature of the civil war, the entrenchment of political opinions on both sides the nieces of Sean Hunter are clear that the family was never divided. In 1942 Christina applied successfully to have her brothers military service medals awarded to her as his eldest surviving relative. (Talking to the family members in preparing this article, it is interesting to notice that they speak of individuals such as Michael Collins, Countess Markievicz, and Cathal Brugha with equal respect, and carrying no trace of divided loyalties or bitterness).

The death of Sean Hunter

A sergeant Major in the National Army Transport Corp, Sean (Johnny) Hunter was on active duty at Gormanstown Camp on Friday 6th October 1922. At approximately 3.30pm he was shot in the throat by Lieutenant Frank Teeling.

Commandant O’Malley (second in command at the camp) was quickly on the scene, and observed Sean as having a “gaping wound in his throat” and as “bleeding considerably”. On being informed that he had been “accidentally shot by Lieut. Tealing (sic)” the Commandant “asked Lieut Tealing to give me his revolver which he did”. Sean was removed to the camp hospital and an officer detailed to gather statements from eye-witnesses. The statements give remarkably similar accounts of the shooting- Frank Teeling was sitting in a stationery crossley tender. Sean came over and started talking and joking with him and a shot was fired by Teeling.

“I was sitting in drivers seat waiting to start off. Sgt. Major Hunter came down and stood on right of vehicle near me. He was passing jokes with officer sitting near me. I heard a revolver shot and saw Hunter fall down. I saw a revolver in officer’s hand. I think I would recognise officer again”. (John Keith, Transport Driver)

“I saw Hunter standing at side of car. I heard a shot and saw Hunter fall. I first thought it was a joke, and then I saw officer run around to Hunter and kneel down beside him. Hunter put his arms round officers neck, and said “it’s all right Frank, don’t worry, it was only an accident” and Hunter kept repeating this remark when going to the hospital”. (Thomas McGurrell)

“Sergt. Major Hunter came over to the car and stood on the ground on driver’s right hand side. Hunter began to talk to Teeling, and the latter commenced fooling and tricking with him .Teeling placed his revolver on the side of the tender, with revolver pointing to Hunter. Hunter said “I am not afraid of that”. The revolver went off wounding Hunter in the throat. I believe the shooting to be purely accidental”. (Lieutenant John Foy)

“I heard a shot, and saw Hunter fall to the ground. I saw Hunter hold up his head, and he said “I am done for, Frank” and then say “It is all right Frank, don’t worry. It was only an accident”. I saw officer kissing Hunter when the latter was lying on the ground. I think I would recognise the officer again”. (J Dunne, Transport Fatigue)

A report from the camps medical officer the following day (7th October) made grim reading:

“Sergt. Major Hunter had a restless night. He continues to breathe through the entrance wound in his windpipe. Haemorrhage from the injury to the right lung seems to be controlled, and his general condition seems to be unchanged. His chances of recovery are remote, and have not improved.”

Sean died in the early hours of Sunday 8th October. His passing is recorded in this letter from the camp commander to G.H.Q., Portobello Barracks:

“I regret to have to inform you that Sgt. Major Hunter died here last evening at 5.30 o’clock. The Commander-in-Chief and the The Chief of Staff were here at the time and I informed them of same , and having consulted them I got in touch with the coroner for the district and an inquest was held here to-day. The finding of the jury was that the shooting was “purely accidental.”I am having the remains of Sgt. Major Hunter sent to Portobello this evening at the request of his parents, and I presume arrangements will be made for his burial from there.”

Sean was buried in Glasnevin Cemetary.

While the inquest may have concluded that the death was “purely accidental” there was some speculation afterwards as to the nature of the shooting. Just two months after the incident an urgent Dail Question was raised on the matter:

“To ask the minister for defence if he is aware that a report has been circulated that the late Sergt. Major Hunter who was stated to have been accidentally shot at Gormanstown Camp on Friday 6th October was really shot by an officer as a result of a quarrel arising out of a game of cards and if he will cause enquiries to be made into the matter”. (Padraig MacGamhna)

The reply given by General Richard Mulcahy on the 4th December simply repeated the inquest finding of “purely accidental”, adding that “The parents of Sergeant Major Hunter were present at the inquest.” It would conclude: “I am not aware of the rumour that Sergeant Major Hunter was shot by an officer as a result of a quarrel rising over a game of cards.”

Frank Teeling

It is not our intention to speculate or play ‘history detectives’, but it is fair to say that subsequent developments in the life of Frank Teeling add credibility to suspicions about the true facts of the shooting of Hunter. We intend to cover the history of Frank Teeling in greater detail at a later date, but some aspects need to be described here to put the shooting of Sean into perspective.

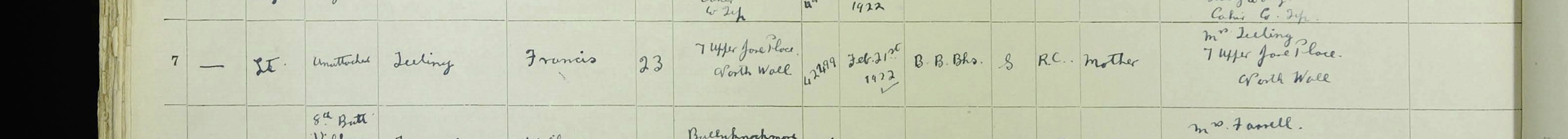

Frank Teeling lived at Number 7 Upper Jane Place, located just off Sheriff Street. From 1917 he was a member of the Dublin Brigade, Irish Republican Army. In the space of a couple of years in the early 1920’s he would go from being one of the most famous republican figures in the country , to one of Irelands most hunted men and ultimately a major source of embarrassment to his comrades.

He was a participant in the Bloody Sunday shootings in November 1920, and was the only republican shot and/or captured during the entire operation, though others were arrested throughout the following weeks. He was part of the team that entered number 22 Lower Mount Street, and shot dead a British intelligence officer. A passing Black and Tan patrol was alerted and tried to enter the house. The gun-men escaped over the back garden wall except for Frank who was shot, wounded and captured. He was almost executed on the spot – a gun was put to his head, and a countdown began when an officer intervened. Teeling was tried for the killing of Lieutenant Henry James Angliss, an intelligence officer whom Collins had unsuccessfully targeted on a previous occasion. In January of 1921 Teeling was found guilty and sentenced to death. His fate became of particular concern to Collins and the republican movement. On the 21st of February he was one of three men who earned their place in Irish prison history by escaping from Kilmainham Gaol. Upon achieving his freedom, Teeling was safe-housed for some time at number 1 Leinster Avenue, North Strand, the home 1916 veterans and republican stalwarts Martha and Michael Murphy .He maintained his active involvement, and in February 1922 he joined the National Army with the rank of Lieutenant. He took part in military actions against Republican forces in Dublin, Clare and Limerick, where he was wounded.

On the 6th of October of 1922 he fired the fatal shot that killed Sean Hunter. Living and working in such close proximity within the North Docks it is probable that the men knew each other for many years outside of military and political matters. However, it is a certainty that as members of the Dublin Brigade and through their involvement in military operations (including Bloody Sunday) and their decision to join the National Army that they had some kind of relationship. The eye-witness accounts all refer to some degree of banter between the men and clearly indicate that they know each other. The official record of Sean Hunters shooting records the incident as “ purely accidental” but as seen above questions were raised immediately afterwards but dismissed. Teeling was soon to become a controversial and notorious figure, yet despite his subsequent behaviour, and everything that has been written since about him, no reference to the death of Sean has ever been included. By November , a month after the incident Frank was listed as a resident at Marlborough Hall, a military convalescent home in Glasnevin.

November 12th 1922 – Frank listed as resident at convalescent home resident . (He joined National Army in February 1922)

The further career of Frank Teeling in the national army was short lived. On the 23rd of March 1923 he shot dead a member of the Citizens Defence Force, William Johnson, in the Theatre Royal. Both men were armed. Teeling was charged with his murder, but was convicted of manslaughter and received a sentence of 18 months imprisonment. The judge voiced the opinion that ‘through drink he had allowed his mind to be dethroned’, and justified his leniency ‘on account of the state of his mind’.

However, at the time of this incident Frank Teeling was already a cause of concern – and over a month prior to Johnson’s death General Richard Mulcahy warned that Frank “had publicly misconducted himself in such a way on a number of occasions as to run the danger of bringing serious discredit to us”. A cheque for £250 had already been made out to Frank and he was encouraged to leave the country and never come back.

Frank Teeling was undoubtedly a very disturbed man. A study by Anne Dolan of Trinity College entitled “Killing and Bloody Sunday, November 1920”opens with the details of Johnson’s death and examines the impact participation in violent activities can have on those involved. She quotes a 1921 report from a republican officer on the behaviour of certain men – “I candidly believe that the present strains on their nerves is too much for them and has left them in such a condition that the taste of whiskey leaves them violent lunatics, and would strongly urge – after watching them for about three hours – that they be given a rest from all arduous duty.” Many of the generation that participated in and witnessed the violence in these years were greatly disturbed by the events – some adjusted to the trauma and some didn’t, the impact on their mind manifesting in many different and destructive ways .Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or ‘Combat shock’ was not recognised as the affliction it is now – the First World War , the Easter rising , the independence struggle and the Civil war all created new sufferers , but there was no recognition of , or effort made to assist these people. Frank Teeling was surely one of these, and the only solution offered was to pay him to move “out of sight and out of mind” to avoid the embarrassment. Department of Defence correspondence from 1925 (marked private) confirms“Certain monies were made available to enable him to emigrate when he was released from Mountjoy in 1924, and the monies passed through me.”

It is In light of our new understanding of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that we should consider the death of Sean Hunter and the culpability of Frank Teeling. It may well have been an accident as portrayed, simply comradely horse-play gone wrong, or perhaps it did have it’s origins in a previous disagreement? Either way it was possibly extenuated by Franks increasing volatility and recklessness. But we do not know the impact that the death of Sean had on Teeling. All contemporary evidence relating to Teeling’s behaviour begins immediately in the period after Sean’s death, and we should consider the possibility that the shooting of a neighbour and comrade contributed to his mental deteoriation, rather than being caused by it.

Remembering ‘Johnny’

The memory of Johnny’s death was passed on to the family in different ways. The parents of Eilish and Phil were republican activists and their involvement continued for many years. As girls they knew Kathleen Lynn, Peter Carpenter, Rosie Hackett and Bob DeCouer. However, as Eilish explained “Mum didn’t talk very much, it wasn’t until she was dying that she spoke” about these events. One of her wishes was that the memory of her brother would never be forgotten. Betty’s mother (a decade younger than Christina) spoke more openly:“My mother always knew about it, she would always talk about it. She wouldn’t tell you the name but she knew the person involved… It was she that told us about Johnny being killed and the chap that killed him being sent abroad. Imagine the government sent this fellow abroad after killing two people at this stage. And he came back…” The family do not accept the official verdict – “It wasn’t an accident, even though it is officially written down as an accident “. However, the suffering of their uncle is what sticks in their mind – “what really gets me is that Johnny was left lying for days in a hospital, breathing through a hole in his throat and nobody done anything for him.”

The memory of Sean Hunter – a son, a brother and an uncle has never faded. As Betty explained: “Mammy quite often mentioned that her mother had paid for a stained glass window …in Gormanstown” and at “Arbour Hill, the stations of the cross…she contributed to these things in his memory”. In 1969 Gormanstown camp became a refugee centre for families escaping from the violence that had erupted in the six-counties. Eilish and her husband were amongst those who volunteered to assist the relief effort, and while here she recalls being shown the window “erected in honour of Johnny”. Christina Crothers successfully applied for and was awarded her brothers Service Medal for the years 1917 to 1921.