Feb 02

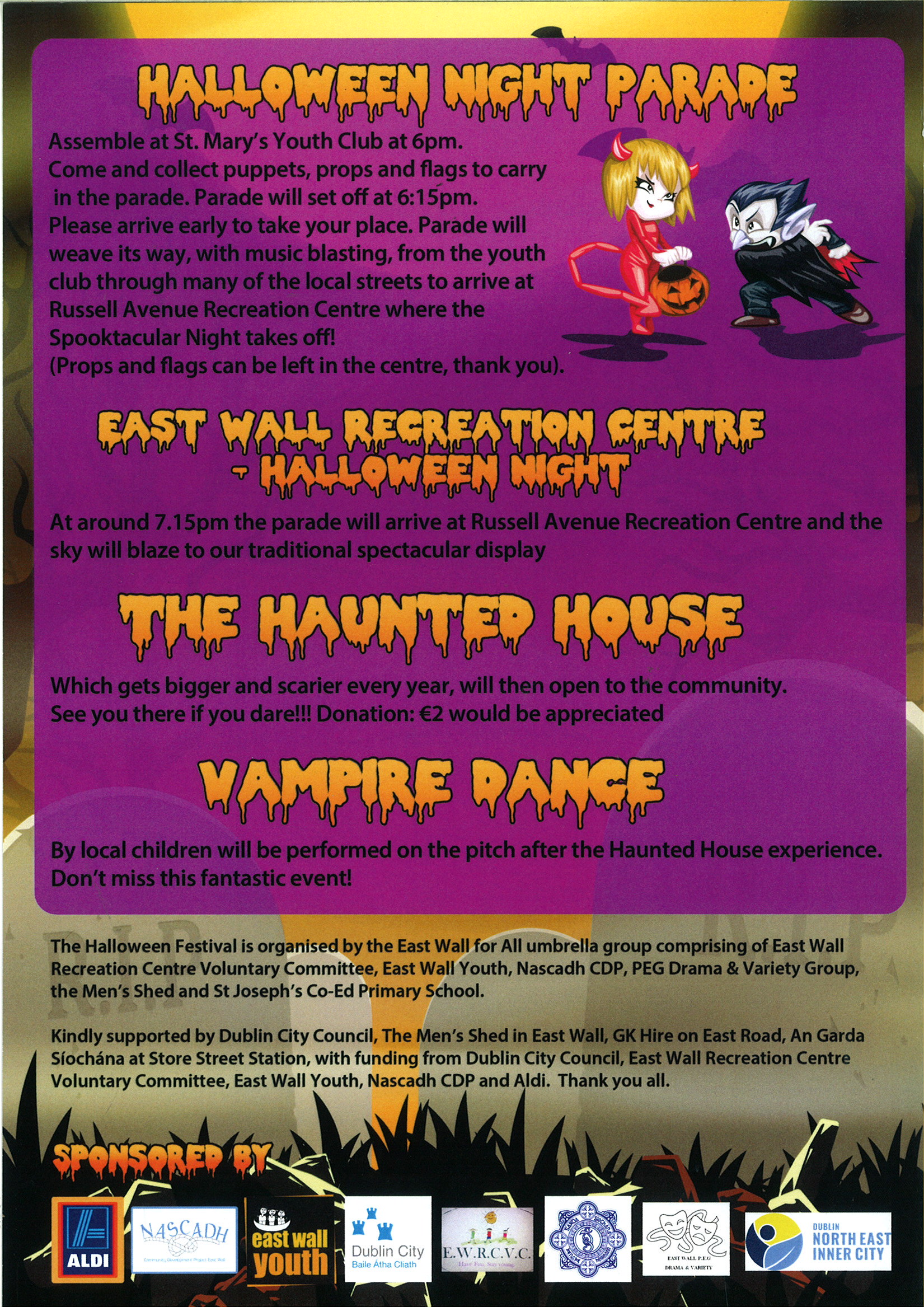

Up in Smoke – the tragic saga of Virginia House, East Wall Road.

“The first high-explosive shell of the long promised second battle of Clontarf has landed on the East Wall Road and blown an Irish firm out of existence and 300 Irish workers out of employment …”

It was a building many associated with industry in the area – some remember it was Wiggins Teape , older residents recall it as Fry-Cadburys . It’s demolition in controversial circumstances in 2001 is still a sore subject for many locals . It was originally known as Virginia House , and this is the fascinating story of it’s early days , one which was tied up with the political turmoil of the day.

On February 16th 1932 Eamonn DeValera led the recently formed Fianna Fail party into government and would retain power for most of the remaining decade. As Charles Dicken’s once put it “it was the best of times, and it was the worst of times,” depending on your perspective and location. Kathleen Behan, then living at 18 Russell Street off the North Circular Road, recalled it as an era of supping “sorrow out of a long spoon.” For her family it was a time of soup kitchens and visits to the pawnshop, with dole queues four deep and winding around the corner from the dole-office on Gardiner Street. She recalled on one occasion, cooking a pincushion stuffed with oatmeal as she had no other food available.

The Eucharistic Congress arrived in Dublin from the 22-26th June 1932 to celebrate the 1700th anniversary of the coming of St. Patrick to Ireland and a rapidly growing Dublin Port soon found itself the location of numerous “floating Hotels” as Harbourmaster John Henry Webb brilliantly improvised in the Docklands area to accommodate Dublin’s lack of tourist bed-spaces. Over a million people attended the closing mass in the Phoenix Park tantalizingly suggesting the potential of a buoyant future Tourist Industry. However, by the end of the month DeValera had Ireland engulfed in an economic war with Britain which depending on what you were engaged in meant a probable boom or bust. For residents in the Docklands this would have mixed results.

Derryman Tom Gallaher began his career hand-rolling tobacco and selling it from a cart. However, after his move to Belfast, his astute business acumen, would see his company rise to being one of the largest Tobacco producers in Europe and his factory, (spread across seven acres on York Street), was the largest of its kind in the world employing 3000 people by 1907. Twenty years later they were producing 40,000 cigarettes per minute with their Park Drive brand becoming one of the markets leaders. The company opened factories at London and owned tobacco plantations at Virginia in the USA. They were also among the largest buyers of raw tobacco on the global market. In 1908 Gallaher bought the site of the recently bankrupted Dublin Distillery on Pearse Street for £20,000. Interviewed by the Irish Times after the auction he refused to comment on whether he intended producing tobacco products at the location or retain it as an investment. They would quickly develop an unassailable position in the southern Irish Cigarette market and a sizable part of the sales in pipe tobacco and snuff as they developed what an Ulster writer would call “an enormous vogue during the heydays of the Irish Revival movement.”

Gallaher was an enlightened employer, being one of the first in Belfast to reduce the working week from 57 to 47 hours and introduced annual paid holidays. His factory served hot meals at cost price to their staff at lunchtimes and he seems to have been held in high regard by all those who worked for him being described as “courteous, kind, and generous.” He was noteworthy for refusing to bow to sectarian pressure to replace his Catholic workers during tensions in Belfast. However, he could be tough and inflexible when required particularly with Trade Unions as Jim Larkin would learn to his costs during the 1907 Belfast Dock Strike. When Tom Gallaher died in 1927, he left a personal fortune of over £500,000 or about 25 million in today’s money. Lacking a male heir, the role of leading the company fell to his nephew, John Gallaher Michaels, (known as J.G.), who had been manager of the company’s American operations.

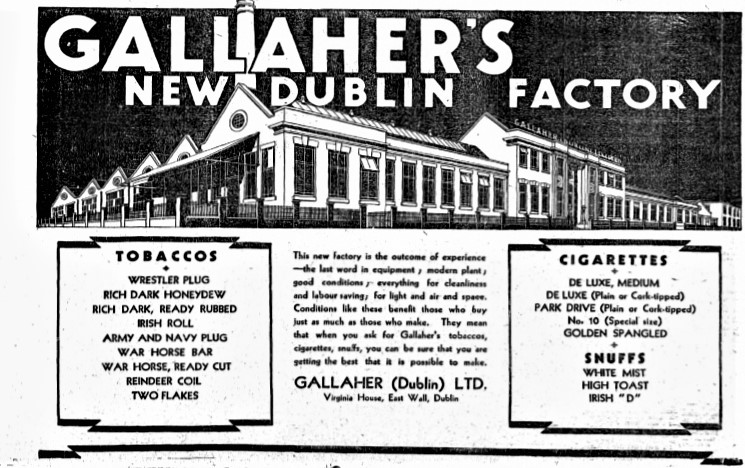

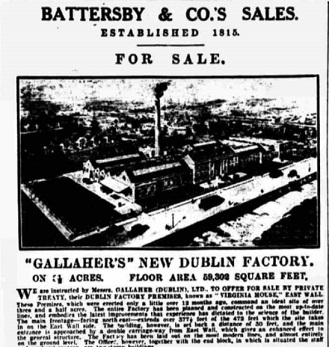

Like his uncle, Michaels lacked a male heir, but it still took people by surprise when he decided to sell all the share capital in Gallaher’s to Constructive Finance & Investment for several million pounds who in turn offered the shares to the public on the open market in 1929. Michaels was struck down with pneumonia in October that year so it may have focused him on his imminent mortality. He would suffer indifferent health up to his death in 1948. That same year Michaels began negotiations with the Saorstat Government regarding the opening of a factory in Dublin. As rumours began to spread it was assumed that Gallaher’s would acquire the recently closed Goodbody’s Tobacco Factory off the South Circular Road. The company had been in business almost 100 years and fell into voluntary liquidation in 1929 with 250 mostly female workers losing their jobs. When the announcement finally came it was that the factory was to be located on a green field site consisting of three and a half acres at the junction of Church Road and East Wall Road. These were badly needed jobs and the factory would, as one writer put it, “form no mean acquisition to a city with a merited pride in its leading buildings.”

The location would probably have been familiar to the management of Gallagher’s. During the recent War of Independence (and subsequent partitioning of the country) Gallaher’s had featured prominently in local attacks during the Belfast Boycott campaign of 1920-21. The Dublin Docklands area had a strong Socialist and Republican tradition , and the local Irish Citizen Army carried out numerous operations which saw boycotted produce , including Gallaher’s end up either in Spencer Dock or the Royal Canal at Charleville Mall. Similarly, the Dublin Brigade of the IRA intimidated local shops such as the Bayview Stores on the North Strand Road, while a Belfast Sales Rep was tarred and feathered and chained to the only public railings in the area at the Ivy Church.One report claims that in September 1921 shots were fired in the direction girls on their way into work at a Gallagher’s premises although nobody was injured. There were similar incidents throughout the country. At the time Gallagher’s virtually dominated the Cigarette market in the southern and western counties which would eventually become the Saorstat or Irish Free State. Ultimately, they were driven from this market. However, they fared somewhat better than their fellow Belfast manufacturers, Murrays, producers of renowned tobaccos such as Erinmore and Yachtsman’s Navy Cut, who had their premises on Talbot Street burnt to the ground in an arson attack.

Despite this Tom Gallaher had always prided himself on retaining the Independence of his company from the global conglomerates such as Imperial Tobacco Trust or The American Tobacco Corporation and took delight in featuring the Irishness of his products in their advertising. The above picture is just one example of the type of comely maidens which adorned Gallaher’s advertisements (and would no doubt have delighted Eamonn DeVelera). Despite being in a different jurisdiction after partition Tom Gallaher took a great interest in the industry on both sides of the Irish Border and was an enthusiastic supporter of attempts to grow native tobacco. In 1906 he purchased the entire crop grown at an experimental farm pioneered by Senator Nugent T. Everard at Randalstown County Meath. By 1930 this had expanded through several counties with one enterprising Roman Catholic Priest starting a co-operative cigarette factory using locally grown tobacco at Wexford. In 1923 the politician and diplomat Patrick McArtan had worked on a plan with Tom Gallagher and Irish American financiers to save the native Irish Tobacco industry in the Saorstat from what he perceived as a potential takeover by the Imperial Tobacco Trust. Indifference among members of the Cumann na nGaedheal government ultimately made it impossible and shortly afterwards Imperial Tobacco began to establish a significant presence in the market leading to seven long established Irish companies such as Goodbody’s failing between 1924 and 1930.

The site of Gallaher’s new factory had been part of the lands belonging to the Nugent horse-dealing family. James Nugent had been a substantial supplier of cavalry horses throughout Europe. Following the outbreak of WW1, he felt honour bound to refused to condemn his former clients in the German army, (despite being no longer able to deal with them because of the war), while engaged in a sales meeting with their British counterparts. Appalled the British withdrew from negotiations and Nugent effectively lost the most lucrative part of his business at a time when it was about to boom. By 1922 he needed finance and so borrowed £2,500 from the National Irish Bank placing the land as security. Unable to discharge the debt the Receiver took it over in 1923, leasing a number of plots, and ultimately selling a section to Gallahher’s in 1929. This enabled Nugent’s son Bernard to discharge the family debt. They would then reinvent themselves as trainers in the horse racing industry and play a leading role in developing legendary jockey Pat Taffe.

By any standards this was exactly the type of flagship project that the embryonic Saorstat needed as a confidence building measure. Lever Brothers had led the way with their redevelopment of the old Barrington’s and Dublin Glass Bottle Company site at Castleforbes Works on Upper Sheriff Street. In 1930 Dublin Port announced an extensive land reclamation programme around Alexandra Road. Ship tonnage passing through the port had more than doubled between 1929-30 while the Port had spent £40,000 on new storage areas for tobacco. However, these advances had to be balanced against some of the new state’s largest employers such as Jacobs who had established their Aintree subsidiary as an independent company in 1922 and were now spread over 30 acres at Liverpool. By 1932 they were employing 3000 people over there and warning that any new tariffs on their products would lead to production moving from Dublin to Aintree. In 1933 Guinness began the construction of their Park Royal Brewery near London. They had temporarily moved their HQ there during the treaty negotiations of 1922. The loss of either of these companies to the state, both of whom were significant employers, would have been devastating. Meanwhile long established businesses and large employers such as the Anchor Brewery began to fail or close.

Against this background the announcement by Gallaher’s was to be welcomed . “In these days when the decline of Industry is almost the despair of the Statesman and the Economist and when retrenchment rather than expansion is in keeping with the times, the stimulus of a tonic is afforded by the contemplation of such a magnificent new factory as that just erected by Messrs Gallaher (Dublin) Limited in the Irish Free State Capital” was one writer’s comment on viewing the new building.

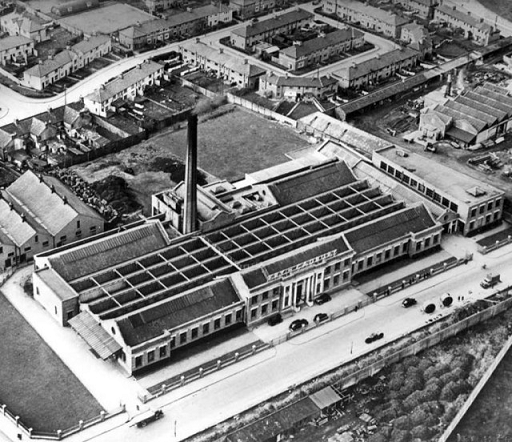

Designed by John Stevenson of Samuel Stevenson & Sons Architects of Belfast, this was conceived as a landmark development which would create confidence in the new state. The main entrance was on East Wall Road extending 377 ½ feet along the 472ft wide site and set 30ft back from the roadway, enclosed by pretty wrought iron railings by J. C. McGloughlin of Pearse Street. The facing of the entire building was in attractive Dolphins Barn brick, and the overall construction, largely using steel frames and reinforced concrete, was built by M’Laughlin & Harvey Contractors of Dublin. In fact, wherever possible, local companies had been used as either suppliers or contractors acting as a showcase of what the Building Industry in the Saorstat was capable of. Not surprisingly organizations such as the Engineering and Scientific Association of Ireland would organize for their members to inspect the project. The overall cost was £100,000.

The main entrance on East Wall Road was through a central revolving door leading into a spacious hall with a large teak horseshoe shaped reception desk. The elaborate polished-plaster walls were interspersed with black marble finished pillars with ionic caps. The passageways leading off this into various offices had black and white terrazzo floors leading to the claim that they offered “every facility for the efficient dispatch of business in the most pleasant and up-to-date conditions and where the atmosphere is such as to generate staff pride in their surroundings.”

The workers entrance was on the Church Road-side of the building as was the delivery area for stocks and supplies. The Timekeepers Office, Cloakroom, Leaf Sample Room and Laboratory, Stockrooms, Wages Office, and Gatekeepers apartments were all located here. Behind these were the Boiler House, Pump Rooms, Air Conditioning Plant, and Snuff Department. The Air Conditioning designed by The Aerozone Air Conditioning Company, was state of the art and not only kept the various tobacco products moist but supplied cool fresh air for workers throughout the building.

At the front to the right of the building was cigarette production with plug tobacco and other products being produced to the left. All were kept on a flat single story level for both efficiency and safety. Management offices and the staff canteen were in a two storey block just off the main factory to the right. A central glass roof over the main production area filled it with an abundance of light making the workplace “bright and cheerful.” Of particular note at the time was the advanced sprinkler system fed by two separate water supplies which would protect the factory from any potential fires.

Central to the production process was a German Machine, described as “one of the wonders” by a visitor on opening day. It could produce 2,200 cigarettes per minute or 132,000 per hour. As tobacco entered one end, paper in reels of two miles long enter at the other and as the paper had the brand logo printed the tobacco was formed into tubes, wrapped by the paper, and came out as a fully formed cigarette. The same witness was impressed by the “intelligence” of another machine which could count the cigarettes into tens, wrap them in tinfoil, slip in picture cards or coupons, and then deliver a finished product for the packaging department. “No human workers could compete with these robots,” he concluded. Like many companies Gallaher’s were using a gift coupon system to promote their products and this witness calculated that in an hour it could produce enough coupons to secure the ultimate prize of a motor car.

Building had been somewhat delayed through the Dublin Building Lockout of 1930-31 which also effected the developments of the new housing estates at nearby Marino and Donnycarney. Initially production was set up at a temporary factory on the Rathmines Road in April 1930. Gallagher’s noted this in their first advertisements when they apologised for delays in delivering their products since opening in February at East Wall “which for the moment we are unable to deal with.” However, they claimed they had had “an outstanding welcome” to the Saorstat market and the patronage they had received would “ensure the success of Dublin’s newest factory.” In his speech at the opening of the factory J. G. Michaels paid particular tribute to the, “competent, efficient and experienced” East Wall staff through whose efforts they had been able to open in just three weeks after the building’s handover and predicted that with their “help and loyalty” they would be just as happy as their colleagues in Belfast. He claimed Gallaher’s “worked with their workers and tried to make them feel that the management studied their interests from beginning to end. They were out to make the new factory one of the happiest in the Free State.”

When the factory opened 300 staff were employed, of whom around 200 were mostly adult women. 50 of these had previous experience having worked for Goodbody’s as did many of the Clerical and management staff. However, an Evening Herald reporter who visited the factory just before production commenced was told that this was only the beginning and that the project could eventually employ up to 600. While initially many of the key personnel had come down from Belfast to set up at Rathmines Road by the end of the first year of trading these had been replaced by local workers many promoted from the shop floor. Wages for the women were above the industrial average and by 1932 the company had begun to discuss the introduction of a productivity bonus in the future. However, when the ATGWU (Amalgamated , Transport & General Workers Union) applied for an increase for the male workers towards the end of 1931 they were told they would have to wait until the company was better established. In a show of how Gallaher’s treated their workforce on the 3rd April, 150 staff from the Belfast factory were taken to Dublin and after lunch and a tour of the city were brought to East Wall to showcase the new factory and meet the Dublin staff. Then in a novel idea, courtesy of Bohemians FC, both sets of workers headed to Dalymount park for a “challenge” match between teams from both factories.

Throughout 1931 Gallaher’s proceeded with one of the largest and most aggressive advertising campaigns which had ever been seen on the island of Ireland up to that date. Regular advertisements were placed in the National Daily and Sunday Newspapers while all the major city-based papers around the country were also targeted. It was at an unprecedented level at which none of their competition could compete. The largest local producer of tobacco products was P.J. Carroll of Dundalk who also offered a coupon scheme which you could collect and convert into luxury items. Gallaher’s had a similar scheme from day one but with that tantalising top prize of a motor car. Not surprisingly they would claim that their total investment in the Saorstat project by 1932 was £200,000.

Carroll’s factory in Dundalk was one of the Saorstat’s flagship companies and in 1930 was described as “the largest and most up to date cigarette factory in the Irish Free State.” From early beginnings in a humble, grocers shop it had grown into a substantial employer in the County Louth region. Much of their marketing success was down to their coupon scheme, available with Sweet Afton cigarettes which could be collected and exchanged for prizes. Where possible these were of Irish Manufacture thus showcasing the resources of the Saorstat. Numerous shops around the country contained window displays showing the luxury goods obtainable through the scheme. Gallagher’s not surprisingly copied the idea but offered extraordinary top prizes such as the motor car.

As early as 1923 Imperial Tobacco had begun to court the Cumann na nGaedheal government then in power. W.D. & H.O Wills opened a factory at Glasnevin in 1924 on the back of announcements the previous year by John Players and William Clark’s that they were looking for suitable sites for factories in Ireland. All of these companies were members of the Imperial Tobacco Trust. For J. J. Walsh, T.D. and Postmaster General in 1923, this was another attempt to “kill off the opposition” after which “the combine will retreat to their English base and exploit from there.” Walsh had little long term hope of large scale employment from the “foreign” tobacco industry. Despite this employment in the Industry had increased by over 1200 jobs between 1922 and 1930 largely due to the English companies creating an Irish operation. The failure of Goodbody’s seems to confirm Walsh’s prediction and then Imperial Tobacco, alarmed at the rise of Carroll’s share of the market, began to threaten customers with a withdrawal of their seller’s bonus unless they removed the Carroll’s displays from their windows. Imperial’s deal with retailers allowed for 50% of all available window space to be devoted to Imperial products however they were not prepared to give over the other half to the opposition. Few tobacco dealers could afford to give up their seller’s bonus, let alone popular Imperial Tobacco products, so that in February 1932 the magazine Honesty would report that only one location in Dublin still displayed Carroll’s gifts and that was the Restaurant of the Savoy Cinema. In January 1931 the magazine accused the then Minister for Industry and Commerce of standing by while Carroll’s were either put out of business or forced into the Imperial Tobacco family of companies.

There was much anticipation and speculation about Fianna Fail’s first Budget delivered on the 11th May 1932. As Labour TD William Norton commented it was in some degree a “Budget for the plain people” insofar as it made a “substantial advance” in the provision of housing and had a “note of sympathy for the unemployed.” However, for many TD’s this was a budget designed to lengthen the Dole queues. One of the most controversial taxes was on the new tobacco factories developed in the Saorstat post 1922 who would have a special tax of 7d per lb of tobacco used in their manufacturing. Effectively this would only apply to companies owned by multinationals from outside the Saorstat and give a distinct advantage to the old native firms. Part of the thinking behind this seems to have been influence by the actions of Imperial Tobacco against Carrols and Fianna Fail decided to take action to protect native tobacco companies. However, as one tobacconist writing as “snuff” would claim, Irish companies would be better off sending their sales staff round the country rather than getting protective duties from the government. He only stocked Imperial products as they were the only companies whose reps visited him. He had never had an Irish Company’s rep call at his shop.

At the beginning of June 1932, J.G. Michaels issued a statement to the staff in East Wall.

“It is with the greatest regret that we have to inform all our employees that owing to the heavy losses sustained by us as a result of the differential duty rate imposed by the recent Budget it is now impossible for us to carry on our business. We have made every effort to secure equal treatment with our favoured competitors. But with no success.

We are, therefore, most regretfully compelled to give our employees one week’s notice expiring on the 8th June 1932, from which date they will be employed from day to day until our factory duty paid stocks are exhausted. Any employees finding other employment will be released on request.” Regarding the workforce Michael’s said that the situation was tragic, and in tribute to them stated that they had “at all times given us of their very best and have worked faithfully and well.”

During the 1907 Belfast Dock Strike, Tom Gallaher, who had played a crucial role in the development of Belfast Port, was threatened by James Larkin that he would spread a sympathy strike into Gallagher’s tobacco factory on York Road. Gallaher’s answer was that he would shut the factory down and move the entire production to London making the 3000 staff redundant. Larkin backed off. Faced with what he felt was a similar situation J.G. Michaels announced the imminent closure of Virginia House and the loss of all the recently created jobs. He wouldn’t be bullied or treated, as he saw it, unfairly.

It seems unlikely that Fianna Fail had contemplated the severity of Michaels’ reaction. Soon rumours began to be leaked to the press that they discriminated in the employment of workers on the grounds of religion which was emphatically denied by the East Wall Factory Staff. It was claimed that Fianna Fail supporters had offered jobs to 70 of the girls but there was no sign of them materialising. An English company was in negotiation to set up a car assembly plant on the site which never happened and would not have employed women anyway. Naively it was suggested that the factory be seized and run as a workers’ co-operative. Then suddenly stories appeared questioning exactly who were the real owners of the parent company Gallaher’s Tobacco Ltd. The local company had been registered in the Saorstat in 1929 but none of the key shareholders were residents. There had been a flurry of activity on the London Stock Market throughout 1932 and soon people were suggesting that there may have been more to the closure than the Saorstat’s new tariff on tobacco.

While it is difficult to say how much influence events in Ulster may have had it is interesting that an attempt was afoot to encourage Ulster citizens to Buy Ulster or Empire produced good which was directly aimed at imports from south of the border. This may have had some influence on Fianna Fail intransigence. The rumours of the senior company’s recent share sales also seemed to have impacted on many TDs. Behind the scenes the American Tobacco Corporation were attempting a hostile takeover bid and in order to counteract this, 51% of the shares in Gallagher’s were sold to Imperial Tobacco for one and a half million pounds.

At a special debate on the matter in the Dail, Richard Mulcahy of Cumann n nGaedheal had outlined Gallaher’s “Irishness” and pointed out that it was impossible for them to come into the Saorstat in 1922 or ’23 given recent history. He also pointed out that their annual Rates bill paid to Dublin Corporation was £700 in 1931. Fianna Fail had argued that the new tariff was actually below that paid by tobacco companies in Britain. Mulcahy demolished this argument demonstrating that only certain luxury types of tobacco paid more tax in Britain while most general types of tobacco, used in the more popular products, were below the new Irish rate.

As the Irish Women Workers Union represented the largest number of workers at the factory, Louie Bennett led a delegation to Belfast in August to negotiate with Michaels in the hope of saving the factory. The talks were inconclusive, but Gallaher’s agreed to hold off from selling the equipment and machinery at East Wall as she attempted to find a solution. Just before this another bombshell landed as Jacobs announced they were laying off 100 girls and moving those jobs to Aintree. Fianna Fail had also placed a tariff on materials used in confectionary.

From a socialist point of view, it was asked whether the Fianna Fail Government could really argue that Gallaher’s weren’t an Irish Company. Tom Gallagher had always seen himself as Irish (although not necessarily a Nationalist) and it was questioned whether Fianna Fail were now saying that Belfast was no longer an Irish city. The United Irishman newspaper argued that the party was re-enacting the War of Independence through its actions against what was generally seen as a model employer :

“The first high-explosive shell of the long promised second battle of Clontarf has landed on the East Wall Road and blown an Irish firm out of existence and 300 Irish workers out of employment. Mr. Lemass and Mr. McEntee, the blind gunners of Fianna Fail are quite pleased with the work of their heavy artillery. They care nothing what they hit so long as they destroy something. The wreckers of 1922 are still the wreckers in 1932.”

Writing in the trade union paper ,The Watchword, Louie Bennet, of the Irish Women Workers Union (IWWU) stated:

“It may eventually be possible to get the young girls absorbed in other industries, but the prospects for the older women are of the worst, especially for those who have been ten or more years in the industry. Mr, Lemass must surely understand the difficulty of training adults in a new industry, and the practical impossibility of adapting to new processes, workers who have spent years in the same occupation. If Gallagher’s factory goes the more senior employees will have to face a poverty-stricken future. The first casualties in Mr. Lemass’s war.”

Sean Lemass announced that the Government were working on getting alternative employment for the workforce although he couldn’t guarantee that it would be on the type of terms on which they had recently been employed.

[ For a lucky few, jobs would be had at the Cadbury’s Chocolate Factory when it opened on Ossory Road in 1933. Lever’s at the Castleforbes Works, with what was described as “the best jobs in the Docklands” were expanding, but they had a full workforce. The remaining local options for women were far from great. Goulding’s Fertilizer Company had a sack factory on Alexandra Road which employed women. The hours were long and the work back-breaking. Lil Fagan who worked at Goulding’s at a later period remembers it as a “great laugh” because of the camaraderie but they only employed about 12 girls. Lil had previously worked in another sack factory, Smiths on Common Street, with her friends Bluebell Murphy and Dinah Proctor where she “classed” the sacks. She developed TB which meant she constantly had chest problems so she only lasted 6 months in Goulding’s.

The East Wall Packing Company described by one staff member as one of the “Fianna Fail sweat packing factories” employed 52 girls at wages from 4s 9d up to 10s 3d per week packing various products by hand. Other girls were on piece work packing sachets of Epsom Salts at a rate of 2s 6d per ½ cwt (25kg) although this was reduced by 3d in 1934. Six girls were fired when they suggested joining the Irish Women Workers Union. ]

Bennet sought assistance from William Norton, the Labour Party leader in the Dail, whom she hoped might give raise the situation and be a voice of influence in parliament. Norton refused to meet her delegation as the WWUI were non-affiliated to the Labour Party. Gallaher’s had been emphatic- either the tariff went, or the Factory went. Running out of options Bennet achieved a type of deal during a meeting with Lemass. The government would give Gallaher’s an exemption, but Gallagher’s would have to sell 51% of the Irish Company to Investors living within the Saorstat so that it effectively became an “Irish” Irish company. The share sale was to be completed by 1st February 1933, however Lemass noted in Cabinet on the 5th September 1932 that finding the type of capital needed might not prove easy. Throughout the year Newspapers had commented how the wealthy and their capital were fleeing the Saorstat. Two weeks later it was announced that Red Abbey Tobacco in Cork had acquired much of the machinery from the East Wall Factory. A similar announcement heralded the remainder of the machines going to Donegal. The advertisements, first published in June, for the sale of the factory reappeared.

Both Gallaher’s factory and 300 good jobs were lost to East Wall. The company had operated for just eighteen months. Women’s employment just wasn’t a priority for political parties in 1932. In a final effort Bennet tried to extract an agreement from Lemass that the East Wall workforce would get first options on any jobs which became available if and when the factory was reopened under new ownership. She was told there were no jobs for them as companies wanted young inexperienced girls just entering the job market for the first time.

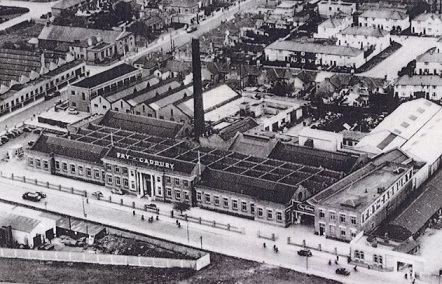

In 1939 Fry Cadbury’s were looking to expand and seeing an opportunity at the vacant Gallaher’s factory promptly moved from Ossory Road. Renamed Alexandra House, the chocolate factory would be one of many East Wallers favourite memories both as a great employer and for the quality of its products often brought home by parents and neighbours for lucky children. Local legend suggests that it’s proximity inspired local chip shop and Ice Cream parlour owners, the Andreucetti’s, to invent the 99 Ice Cream Cone or choc ice. Cadburys remained on the East Wall Road until the opening of their current factory in Coolock in 1964. During the redevelopment of the site a few years ago, Owen O’Flynn, one of those who worked on the building site recalls that the delightfully pungent smell of cocoa was still everywhere.

In 1932 Gallaher’s were the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer in Britain. In 1934 they acquired Peter Jacksons, followed by Robinsons in 1937. Over the subsequent years they would acquire J. Freeman & Sons in 1947, Cope Brothers in 1952, and the prestigious Benson & Hedges in 1955. The alliance with Imperial had been to stave off a hostile takeover bid by the American Tobacco Corporation. However, they retained their managerial independence as part of the deal. In 1963 Gallaher’s once more opened a factory in Ireland at Ayrton Road, Tallaght. Four years later they contacted the IWWU to discuss a new shift system which would facilitate young married women with families remaining in employment.

*********************************************************************************************************************************

This is part of our series of features on industries, premises and public houses in the North Docklands . If you have any material of interest – photos, documents , personal or family recollections then please get in touch .

Any corrections, clarifications or further information please contact us:

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

***********************************************************************************************************************************

Epilogue : By the end of the 1930s Kathleen Behan and her family were living in a house on one of the Saorstat’s new housing estates at Crumlin. Isolated and lacking any facilities, her son, the future writer Brendan, described it as being like arriving at Siberia.

Jan 11

“A DUBLIN TRAGEDY” : The infamous 1908 Fish Street Murder

It was described as “A SQUALID CRIME” , a grim murder , subsequent court-case and sensationalist newspaper coverage which gripped the public imagination . While the names of the victim and perpetrator have long been forgotten , the murder was so infamous at the time that it led to a street name been changed to help erase the memory of the crime. Here is the full story :

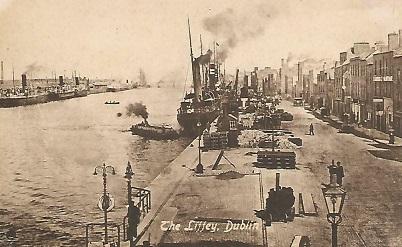

It was unusual for the SS Olive to be on the Liffey. Built in 1893 for the Laird Line’s Glasgow, Dublin, and Londonderry Steampacket Company she usually served the Derry route, although her limited accommodation of 100 beds meant that even on the Maiden City route her appeal was limited. She could, however, handle up to 1000 deck passengers (but even this would eventually see her replaced in 1930 to provide a more comfortable and lucrative mode of travel between Ireland and Scotland). Besides passengers she also carried livestock and general merchandise.

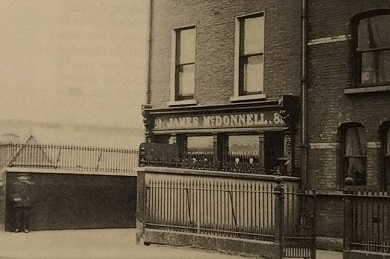

Passenger ships engaged on the Dublin to Glasgow route were known locally as “The Scotch Boats” and moored close to the Fish Street and North Wall Quay junction as the Laird Line’s warehouse and offices were nearby. Early on Saturday the 7th November 1908 several men approached the crew of the Olive. They were Scottish and had been sailing with the Baron Kelvin, a screw steamer Cargo Ship which had been trading between Algeciras near the Bay of Gibraltar in Spain and Ireland. Having returned and unloaded their cargo the previous day on City Quay, six of the crew, not being required for the subsequent voyage, were paid off. Seeking a way back to Glasgow they were directed across the river on the Ferry to obtain passage home on the Scotch Boats. Having obtain berths and loaded their luggage, the young men aged between 19 and 26, set out to find nearby entertainment while they awaited the departure of the ship. Flush with money , which was burning a hole in their pockets, some returned to City Quay and began to drink in nearby pubs with the remaining members of the Baron Kelvin crew while others stayed on North Wall Quay, as James McDonnell’s pub was just a few feet from where the Olive was moored. It would be an eventful evening before they set sail for Scotland.

Around 6.00pm two of the Scots, George Robertson and John Peterson, somewhat the worse for drink, boarded the Olive and promptly began to sleep off their oncoming hangovers. The other four, David Anderson, Neale Gillies, Alexander M’Donald and Thomas Grant continued to drink the final hours away at McDonnell’s before the ship sailed at 10.00pm.

McDonnell’s had a snug, a self-contained compartment with a door and a window giving access to the bar counter so that the more excessive behaviour of the male customers could be avoided. In Dockland’s parlance this was sometimes known as a “Confession Box” and was usually installed for “the auld wans”, older women of the area who liked a drink. Younger women looking for alcohol would either go to a Spirit Grocers or would send a messenger in with a jug or can, to be filled with porter to be drunk at home. Women who went into pubs unaccompanied at that time were usually seen as being of poor moral standing or possibly prostitutes. Unusually on that evening in 1908 three unaccompanied women were drinking in the pub’s snug.

The women lived at No 1 Elliot’s Place a short narrow street which connected Montgomery Street with Railway street in the heart of the infamous Monto Red Lights District. Kate “Christy” Kenny was 38 and had a record of convictions for Sheebeening [running an unlicensed drinking house] and prostitution going back to 1900. (In 1909 she was charged with keeping a brothel at 17 Gloucester Place. Three years later she was arrested for larceny with three others at a brothel in Summerhill, but the case never came to court as the charge was withdrawn). Fanny Langford, aged 34, had been arrested with four other girls for the larceny of £47 in 1905 while working at a brothel in Summerhill run by Thomas and Jennie Blaney. Langford, who seems to have been the ringleader, received the harshest sentence of four months hard labour. Her convictions for prostitution would continue up to 1909 and her arrest records suggest that for much of her life at this time she was homeless or of “no fixed abode” except on the few occasions she was arrested in an Elliott Place Brothel. She died the following year. Both women had been caught up in mass arrests in July and October 1908 as the Dublin Metropolitan Police targeted the brothels, kip houses, and sheebeens of Elliott Place. This may have motivated the women to seek out “safer” pastures outside the gaze of the authorities as North Wall Quay was some distance from The Monto. Prostitution wasn’t unusual in the Docklands area in 1908 mainly in the pubs and areas in the vicinity of City Quay on the southside of the river where numerous ships unloaded their cargoes. However, it was rarer on the northern side where the cross channel passenger services were located. The third woman, Mary Carroll, was a 36 year old widow who had once lived nearby in Nixon Street off Lower Sheriff Street and Common Street. There is no evidence to suggest she was involved in prostitution, but the newspapers would still describe her as being “a miserable outcast” and of “that unfortunate class” of women. The Scotsman Newspaper would also incorrectly label North Wall Quay as a notorious part of Dublin.

Aerial shot of Fish Street (Castleforbes Road) in the 1930′s. McDonnell’s pub is the white building on the bottom left

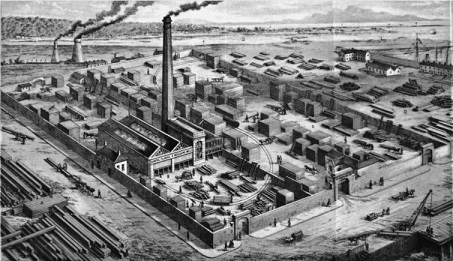

Around 9.00pm the women left the pub followed soon after by the Sottish Sailors. M’Donald and Gillies went aboard the SS Olive while Anderson and Grant after some conversation with the women at the street corner walked into the darkness towards Mayor Street and Upper Sheriff Street. Fish Street (now Castleforbes Road) cut through the centre of the 14 acre site of the various departments of T. & C. Martin’s Timber Works. The street was poorly lit and large consignments of timber were often left along the roadside near waste ground as there were few houses at the Quay end of the street being largely works yards and warehouses.

Thomas Grant, an able seaman who had been part of the Baron Kelvin’s crew barely made it up the gangway as the SS Olive prepared to sail. Questioned by Neale Gillies, Grant claimed that he had been delayed by an occurrence involving one of the women whom he said had been “crushed” or assaulted during an incident involving some soldiers. Gillies found this strange as he hadn’t seen any military on the North Wall however he soon found that members of the 18th Hussars were on board the ship. Still, he found it suspicious that Grant asked him not to mention it to anyone if he had not been involved in the affair.

Kate Kenny had been returning towards the Quay when she saw the prostrate body of Mary Carroll. There was no sign of struggle but there was blood coming from her mouth and nose. Kenny screamed for assistance. David Anderson who had been with Kenny heard her cry out and ran to find Carroll’s lifeless corpse on the waste ground near some logs on Fish Street. Anderson thought he saw a gag in her mouth but couldn’t be certain. They quickly alerted Constable McCarthy who was on duty on the docks that evening. McCarthy attempted to phone the Corporation Ambulance from McDonnell’s pub but the phone at the premises was out of order. A local postman suggested he try the one at the nearby Laird Line Offices. Meanwhile Anderson, hearing the whistle which announced the imminent departure of the Olive ran down the street to catch his ship.

It was 10.30pm when the body arrived at Jervis Street Hospital where Dr. O’Sullivan, the House Surgeon, carried out a brief examination. Carroll had been ill for some time and it was initially believed that her death was caused by haemorrhage of the stomach. O’Sullivan had her admitted to the mortuary while awaiting further instructions from the Coroner. It was only while carrying out a post-mortem the following day that he discovered that Carroll had been stabbed with a long sharp blade to a dept of about 6 inches which punctured her right lung. O’Sullivan’s conclusion was that a single blow of great force had caused her death. The blade had been withdrawn so quickly that the blood had rushed into Carroll’s throat making it impossible for her to raise the alarm although it was subsequently discovered that she had attempted to crawl back towards the pub before losing consciousness. This was not death by natural causes. This was murder.

Kate Kenny described the man with Carroll as elderly, about 60 years of age, with white hair and wearing a dark overcoat and hard hat. She claimed to have been no more than 12 yards away and heard no screams or sounds of struggle. Langford was unable to give any description; however, Kenny’s assertion was somewhat verified by a local youth named Michael Lovatt, who would play a role in subsequent events.

Investigating the murder fell to Detective Sergeant Andrew Lonergan. A Kilkenny man, he had joined the DMP in 1891 later transferring to the Detective Section of G Division in 1896. He had recently been promoted to Detective Sergeant and this would be a case that would enhance his growing reputation which would see him finish his police career as a Detective Inspector. Up to then most of his work involved investigating racing frauds, pickpockets, and counterfeiters. He would be particularly noted for his clever employment of forensics in this case which was still a developing science. Lonergan quickly circulated the description of the elderly man given by Kate Kenny who allegedly ran off in the direction of Upper Sheriff Street. However, he quickly detected that the Scottish sailors who had been in company with the women may have an involvement and passed details onto the Police at Glasgow. Within days the Glasgow Police had tracked down the former crew of the Baron Kelvin and brought them in for questioning. It had taken some effort as they had dispersed across Scotland on their return but by the 11th November five of the men had been tracked down and brought to Glasgow under caution.

A sixth man had left word at his Glasgow lodgings that he was visiting friends at Leith near Edinburgh which the police quickly found to be untrue. However, they did find his kit bag which contained the sheath from a dagger and a sweater with what they believed to be three small bloodstains on the sleeve. Their suspicions aroused, after some intense investigation by Detective Inspector Thompson French, they found that he had actually gone a short distance from Glasgow to a house on an isolated road outside Holytown, Lanarkshire, where French effected his arrest. Lonergan, accompanied by 14 year old Michael Lovett, travelled to Glasgow to attend an identity parade of the suspects. Lovett, whose account of events Lonergan would later describe in court as “something of a Fairy Tale”, quickly identified Gillies and M’Donald and arrangements were made for their transfer to Dublin with the other four Baron Kelvin crew members. The murder had attracted a lot of coverage and the court room was packed to capacity. However, when they were brought into the court to be charged, there was something of a shock for those assembled there. Far from being a white haired 60 year old, the man being charged with Mary Carroll’s murder was the 25 year old, brown haired, able bodied seaman, named Thomas Grant.

Grant was from the Shetland Islands and had joined the 147th Battery Royal Field Artillery on 28th June 1901. Army life didn’t agree with Grant and he deserted on the mouth of Christmas 1902. He returned to the service four months later and after a short prison sentence was dismissed “as no longer required.” Since then he had worked for some years on the American Coasting Service before returning to Scotland. Although he would claim to be single it was subsequently discovered that he was married with a wife named Jessie and a young child. As with most of Grant’s statements during the investigation he was consistently economical with the truth unless proved otherwise.

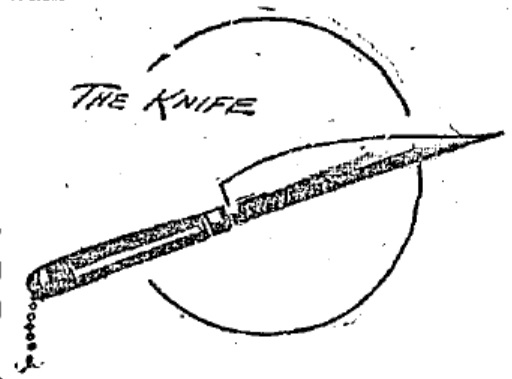

While being examined at Glasgow it transpired that he had purchased an unusual double edged knife from a Spaniard at Algeciras as a present for John Green, grandson of a friend’s mother, at whose house at Holytown, Lanarkshire, he was arrested and the blade recovered. Bizarrely he had produced the knife a number of times on the journey back to Glasgow on one occasion offering it to Neale Gillies to cut bread. He later showed it to a Private George Morrison of the 18th Hussars in the hope of impressing him. The design was unusual and distinctive and seems to have fascinated Grant. Various testimonies at his trial have him fondling it and almost being hypnotised by it. Grant also possessed a small folding pocket-knife, but it was the murder weapon that he consistently produced to show people. It’s distinctive and unusual design was remembered by all who saw it and its shape was consistent with the wound which killed Mary Carroll according to Dr. O’Sullivan. The Doctor described it as a “formidable” weapon.

John Anderson had seen Grant alone in a doorway on Fish Street “as if waiting for someone” shortly before Kate Kenny discovered Mary Carroll’s body. Tackling him on the voyage to Scotland he claimed Grant had shown him the knife and said that Carroll had attempted to “get through him” a euphemism for attempting to pick his pockets. However, the lack of evidence of any struggle cast some doubt on this. Anderson told him that he’d found her dead body on Fish Street to which Grant replied, “It was me, don’t tell anybody.” When Grant’s address at Glasgow was searched his kitbag was found within which was a sweater with three small red stains. It was difficult to say if these were blood stains, and professor M’Weeneys investigations would subsequently prove they were not, but it motivated Lonergan to have the Spanish Blade examined by experts. John Green, the child who had been given the blade as a present, had cleaned it with emery paper, removing any potential external evidence of its use in the murder. However, a cutler on taking the blade apart found traces of what he believed were blood corpuscles under the two sides of the handle. On examination under a microscope by Professor M’Weeney it was confirmed that it was human blood stains and that they were recent. No less than five or six weeks old. M’Weeney claimed they were preserved by Grant keeping the blade in his pocket. Grant’s defence would claim that the blade was second-hand, and that Spaniards used blades the way “Irishmen used their fists”, but this evidence was damning.

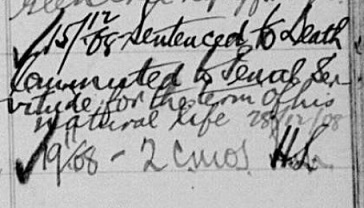

Ultimately the case came down to whether the jury accepted John Anderson’s account of Grant’s confession aboard the SS Olive or the Statement of Kate Kenny who said she had never seen Grant before when asked to identify him in Court. Fanny Langford’s inability to provide any description also created doubt in the jurors’ minds. Anderson, aged 19 at the time, having been arrested at his home in Ardrossan, believed he was going to be charged with the murder and gave a statement to the Glasgow Sentinel Newspaper implicating Grant. It was only after he entered the dock at Dublin that he found out he was there purely as a witness. After some deliberations the Jury brought in a verdict of wilful murder with a recommendation towards mercy. In Passing sentence Justice Wright advised Grant that he would not give him any false hope of a reprieve and somewhat emotionally passed the sentence for Grant to be hanged at Mountjoy Jail on the 12th January 1909. Grant seemed unable to comprehend the implications of Wright’s sentence.

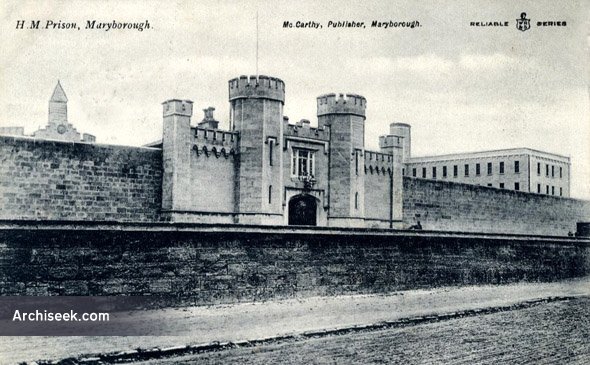

Almost immediately Grant’s defence council, J.G. Lidwell, instigated an appeal for mercy announcing that he was preparing a memorial for the Lord Lieutenant and requesting members of the public to sign it at his offices on Ormond Quay. Having submitted five separate memorials on Grant’s behalf Lidwell receive confirmation on the 28th December 1908 that Grant’s sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life with the sentence to be served at Maryborough [now Portlaois] Prison.

In January 1909 Grant began what should have been a life sentence at Portlaoise Prison. He seems to have been a model prisoner and was recommended for special privileges during his time there. It’s probable that with the excessive amount of drink taken that Grant had killed Mary Carroll in a moment of madness which he later regretted. On 25th April 1917 after only serving eight years of his sentence Grant was released under license and returned to Scotland.

Having been released Grant set about putting his life back together returning to the Merchant Navy and serving as an able seaman for the remainder of the First world War for which the above photograph was taken. There is something haunting about the image as if the life has been drained out of him. Given the amount of alcohol consumed by all parties it’s likely that Grant would be charged today with manslaughter and possibly have served much the same amount of time as he did in the early 20th century. The swiftness of the blow and absence of any evidence of a struggle suggests it was a momentary reaction carried out without any thought or premeditation. While its commendable that so many Dubliners supported J. G. Lidwell’s memorials on Grants behalf, it was also symptomatic of the class system of the time which saw the likes of Mary Carroll as worthless or as the Irish Independent described her, “a miserable outcast.” She consorted with prostitutes and thieves who had records for robbing customers in the brothels they worked in, so Carroll was seen as more of the same even though there was no evidence to suggest she was guilty of either.

Today all the protagonists in the story have faded from memory. At the time it had been widely reported not just in Ireland but had received extensive newspaper coverage throughout Britain where it was often described as “The Dublin Tragedy.” While that title was appropriate, the sordid story of illicit sex and murder lingered long in relation to the area. Fish Street and that part of North Wall Quay would acquire an unwarranted reputation largely based on the infamous murder on the night of 7th November 1908 when three women seeking a quiet drink encountered some Scottish sailors awaiting a Laird Line ship. In 1924 local merchant John Hughes would organize to have the name of Fish Street changed to Castleforbes Road thus wiping out the last link with the infamous murder and restoring the reputation of the street which he felt it deserved.

If you have any corrections, clarifications or further information please contact :

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Dec 15

“North Wall eye-opener” – a Dockland Pub to remember

As a new local pub, “The Bottle Boy”,opens at the location of the fondly remembered “Connors” and “Vallence & McGrath” , we take a look back at the history of this address and the drinking establishments which previously stood there.

The origins of a premises at No.81 North Wall Quay is somewhat obscure. In the early 1850s as sites around it were developed into dockside houses it was a vacant lot owned by the Ballast Board. Evidence suggests the current structure may have originally operated as a hotel or lodging house for those conducting business in the Dublin Port area. Among its residents was John Abraham a cattle exporter who also specialised in Clydesdale Horses which he sold from a yard nearby. In 19th and early 20th Century Dublin, the Clydesdale literally was the “work-horse” which drove the Dockland economy, being the preferred horse-power of many of the Dublin Carters which operated in the area for companies such as Pickford’s on Upper Sheriff Street or Wordies in East Wall before the introduction of the motor car. The last Dockland Carter was Paddy Behan who worked for CIE up to the 1970s. A vivid photograph showing Paddy and his cart exiting Castleforbes Road towards Levers still survives from this period.

In 1861 the Timber Importer, John Martin acquired a site including 81 and 82 North Wall Quay at the corner of Fish Street (later Castleforbes Road) on a 99 year lease. Martin operated a sawing planning and moulding mills and had an extensive warehouse in the area. Their operation would eventually encompass 15 acres on the North Wall. Martins seemed to have had little use for the property at No. 81 and so the following year it was let to James McDonnell who may have adapted the ground floor street level for retail purposes while continuing to rent out rooms in the premises above. McDonnell already had a presence on the Quay at No.60 with an interest in the Big Tree Pub on Drumcondra Road. The spacious retail premises, subsequently added to 81 at street level, was leased by Andrew Stapleton, a Shipwright and Carpenter with many shipbuilding, repairing, and related nautical businesses popping up in the area at that time. William Buckle, Ship Joiner, took over 81 in 1866. It would be 1873 before McDonnell divested himself of his other interests and took over and ran 81 as a Spirit Grocers and Merchants.

However, 1861 is particularly interesting as that year the London and North Western Railway Company (LNWR) moved their operations to the North Wall. McDonnell may well have been anticipating the opportunity to be created by the increased volume of passengers, dockers, and railway workers which would now be passing through, working, or living near that part of the North Wall Quay. McDonnell originally operated at No. 60 as a Vintner or Wine Merchant so it’s likely that his sales were off premises or even wholesale. He may also have been a wine importer. There were several Vintners in the area so there was competition but there was no Spirit Grocers or Public House at the No.81 end of the Quay which was rapidly expanding as the Port grew.

Initially McDonnell’s operated as “J. McDonnell, Grocer, Wine, and Spirit Dealer”, a Spirit Grocers or type of General Provisions-shop within which there was a Spirit Counter where alcohol could be purchased either by the bottle or in a glass. However, while drinks could be consumed on the premises it was somewhat different to a Public House insofar as it was illegal to have seats on the premises. Beer was sold; however, it is worth noting that it came in bottles which the “bottle-boy” used fill from the casks provided by the Brewery. Through this practice, strange and often perplexing Guinness labels turn up at auctions and collector’s fairs which confuse as they have a secondary name under the iconic signature of that brewery’s founder.

In 1880 McDonnell took the bold step of closing the Grocer’s end of the business and converted to dealing exclusively in the sale of alcohol. To facilitate this, a business in Nerney’s Court was purchased in order to transfer the license. At the Court Hearing, McDonnell’s barrister, Mr. M’Laughlin Q.C., broke into an impassionate appeal on behalf of himself as a resident of Gardiner’s Row, (which backed onto Nerney’s Court), describing the “infamous and outrageous conduct” of Nerney’s Court residents who frequented the Public House there as akin to that of “wild beasts.” Judging the case, the City Recorder, (no friend to the consumption of alcohol and with a commitment to opposing the opening of new Public Houses where none had existed before), was persuaded that extinguishing the licence at Nerney’s Court would be a mercy to that neighbourhood. Therefore, with so few public houses in the North Wall capable of providing “comfort and refreshment” for a growing population of tradesmen in the area, McDonnell’s ceased to be a Spirits Grocers, and J. McDonnell Wine & Spirit Merchant’s was born.

McDonnell had political ambitions, was active within Charles Stewart Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party, and would serve between the 1880s and 90s as a representative for the North Dock Ward on Dublin Corporation. In doing so he paved the way for that legendary North Dock Publican/Politician and Lord Mayor, Alfie Byrne.

Ever mindful of his civic responsibility, McDonnell was generous of pocket and his name was regularly found on various charity and church-building subscription lists. Among his local donations was the alter rail at St. Lawrence O’Toole’s Church in Seville Place. He served on the Board of the North Richmond Lunatic Asylum for many years and in 1893 was the Honourable Secretary of the Evicted Tenants Fund set up to support those evicted during Parnell’s Boycotting Campaign. During the “Parnell Split” of the Irish Parliamentary Party, McDonnell ran unsuccessfully as a Parliamentary Candidate for the Harbour Division under an Anti-Parnellite ticket. His greatest achievement, he would later claim, was his involvement while a member of Dublin Corporation in the creation of the Fruit and Vegetable Market at Chancery Place.

James McDonnell died in July 1910 age 83. His son, James McDonnell II, had taken over the business, but he had other interests and soon after leased the pub to a Francis Malone although the McDonnell name remained over the door. Malone in turn appointed a manager, John Shanley to run the Pub. A local, originally from 2 Fish Street (later Castleforbes Road), Shanley had vast experience in the Licensing trade having worked in America, Australia, and New Zealand. Observant to trends, and ever vigilant for opportunity, Shanley noticed the blossoming Tourist Trade in the Docklands driven by companies such as the London and North Western Railway Company. The LNWR had been aggressively promoting Irish Tourism since the time of Queen Victoria and offered a rapid 9 ½ hour journey from London Euston to their station in the North Wall for visitors wishing to explore the Lakes of Killarney, Glendalough, or Dublin itself. Over 1000 soldiers a week passed through the port during the WWI period many of them Anzacs (Australian and New Zealand) visiting their ancestral homeland.

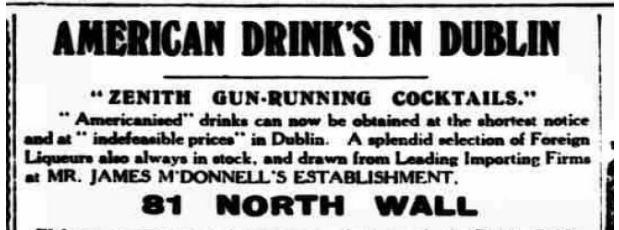

For St. Patrick’s Day 1913, Shanley re-launched McDonnell’s as an American Cocktail Bar, announcing an exotic assortment of bottles “now permanently held in stock” which many locals would have struggled to pronounce let alone have tasted before. This was, Shanley would claim, Dublin’s first authentic American style Cocktail Bar, and offered an eclectic menu of over 60 slings, flips, cups, and cobblers, the piece de resistance of which was their own rum based “North Wall Eye Opener.” Shanley claimed all these “amazing concoctions” could be supplied “at a moments notice.” While the Pub had always been popular with tradesmen and sailors this colourful change in direction, serving what they called a “heterogeneous” selection of drinks, meant the Pub avoided being directly caught up in the conflicts experienced by other Dockland establishments during the Great Strike or Lockout of 1913. With a keen marketing eye, as Irish Politics took a dramatic turn in 1914 through events such as the illegal importation of arms at both Larne and Howth, Shanley introduced a new range for his more daring customers known as “The Zenith Gunrunning Cocktails,” while the truly brave could imbibe with an assorted range of Absinth fuelled mixes – all at “indefensible prices!” They even came up with a marketing slogan of “call your beverage and it’s yours in a second!” Given that the First World War broke out in August 1914 it would seem that the “Gunrunners” were later removed from the menu as inappropriate for the time.

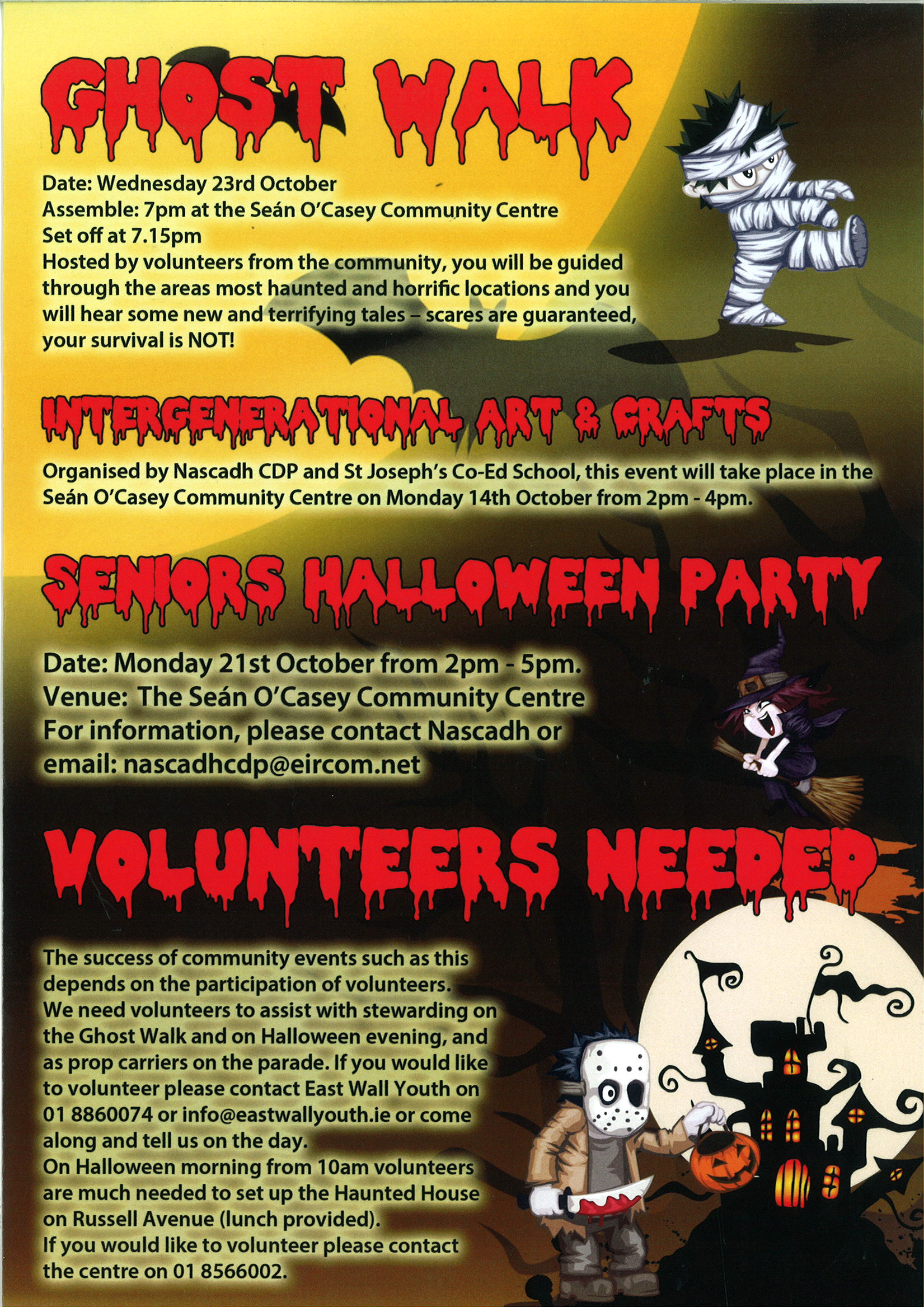

It would appear the War years were kind to McDonnell’s with Dublin embracing the “distinct novelty” of their inventive beverages. However, by the early ’20s it had reverted to its roots of being a good old fashioned Public House serving its traditional customer base of Dockers, Stevedores, Merchant Navy men, Railwaymen, and others earning a living in the Docklands. James McDonnell II died in 1930 and with family interests estranged from the business it was set for auction in December that year. It was at this time that it was acquired by its most prominent owner, John O’Connor, who would take over the license on the 5th August 1931. Ironically, although the name over the door would state O’Connor’s, to its faithful regulars it quickly became “Connor’s” the name which would stick – even after it was sold to Limerick man George Vallence and Tipperary man Pat McGrath in 1980.

Connors was a Union House and staff had served a six year apprenticeship, wore collars, ties, and waistcoats, and quite often with bar-aprons. All bar staff were addressed as “Mister” save apprentices and the Bottling-Boy who was know by their first name. Harry, the last Bottling Boy at Connors, was nearly 70 when he retired and up to that was a regular feature cycling round the Docklands and East Wall, collecting bottles to be washed, labelled, and filled with beer from the casks.

During its era Pubs were for drinking and no food was served. However during lunchtime customers would often purchase some of the legendary “Doorstep” sandwiches in local shops, made from thick freshly cut slices of Batch Loaf, pale or smoked ham cut directly from the bone, or cheese sliced from great slabs, to which the adventurous might have a generous basting of Colman’s English Mustard, and bring them with them into the pub. Lettuce was optional.

Pubs were for men only, but as an increasing number of women began to frequent such establishments, the pub acquired a Snug for “the auld ones”, a type of walled compartment with an entrance door, at which there was a hatch at one end providing direct access to the bar. The idea behind the snug was to protect women from the more excessive behaviour of the bar’s male clientele. Although designed to facilitate women visiting such establishments they also made it possible for couples to drink together, a practice which would have been frowned upon in the open bar. A typical snug would sit up to 6-8 people. They were later replaced by the Lounge Bar.

John O’Connor placed great importance on his staff. They had all served an apprenticeship and when he advertised positions vacant he warned the potential candidate’s that their character would have to stand up to the “most strict investigation”. The quality of their service was a sign of their training as was the quality of the pub’s taps maintained by the bottling-boy once draft beer became popular. Connor’s was one of those pubs known for its “Pint” which meant that the beer was worth travelling for despite its somewhat remote location from the city centre. When the beer was good it was an attraction in itself, but one of the bonuses could quite often manifest itself in the arrival of the likes of Barney McKenna, banjo in hand, or the singer Luke Kelly, both searching for a decent pint. As word spread through the neighbourhood the ensuing session would always be memorable. Luke was local and is commemorated today by the powerful Vera Klute statue at nearby Spencer Dock. John O’Connor died in July 1963 swiftly followed by his wife that November. The family maintained an interest in the pub, but it lacked the personal touch of the man who gave it his name. Somewhat shabby and run down it was taken over in 1980 by George Vallence and Pat McGrath in an attempt to restore its fortunes

Under new management the rundown pub was once again given a facelift with comfortable contemporary furniture installed along with a complete revamp of the interior. But somehow the original charm was missing. Recession in the Docklands affected passing trade and as local residents relocated, business slowed down. The opening of the Point Depot (03 Arena) gave footfall a boost and it seemed like the Pub would thrive once more. However, despite the valiant efforts of the new owners, as far as their regular customers were concerned, it would always be known as “Connors” which particularly annoyed Pat McGrath after all the effort he and his partner had put into the business. The Munster publicans were noted supporters of local youth and sports groups as well as local charities and the pub became something of a social centre under the two men. Then in the middle of the economic boom the premises were sold, and the pub closed. Sadly, the expected development never materialised leaving 81 North Wall Quay as just a decaying memory of times past.

December 2019 sees the return of “Connors” as part of the newly developed Mayson Hotel. The complex acknowledges the area’s maritime heritage with many of their rooms named after renowned Dockers of a bygone era while their intricate wooden floor tiles recalled a local skill of the previous century which was a speciality of T & C Martins timber works. The pub itself pays tribute to the much loved “Harry”, a North and East Wall legend, in its new name “The Bottle Boy” with a terrific selection of old photos of the area’s past adorning its walls. Meanwhile, just over a century after its creation the “North Wall Eye Opener” looks set to welcome guests to the Docklands once more.

December 2019 sees the return of “Connors” as part of the newly developed Mayson Hotel. The complex acknowledges the area’s maritime heritage with many of their rooms named after renowned Dockers of a bygone era while their intricate wooden floor tiles recalled a local skill of the previous century which was a speciality of T & C Martins timber works. The pub itself pays tribute to the much loved “Harry”, a North and East Wall legend, in its new name “The Bottle Boy” with a terrific selection of old photos of the area’s past adorning its walls. Meanwhile, just over a century after its creation the “North Wall Eye Opener” looks set to welcome guests to the Docklands once more.

For corrections , clarifications or further information please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com .

Any personal recollections of these pubs or the general area also welcome .

Dec 15

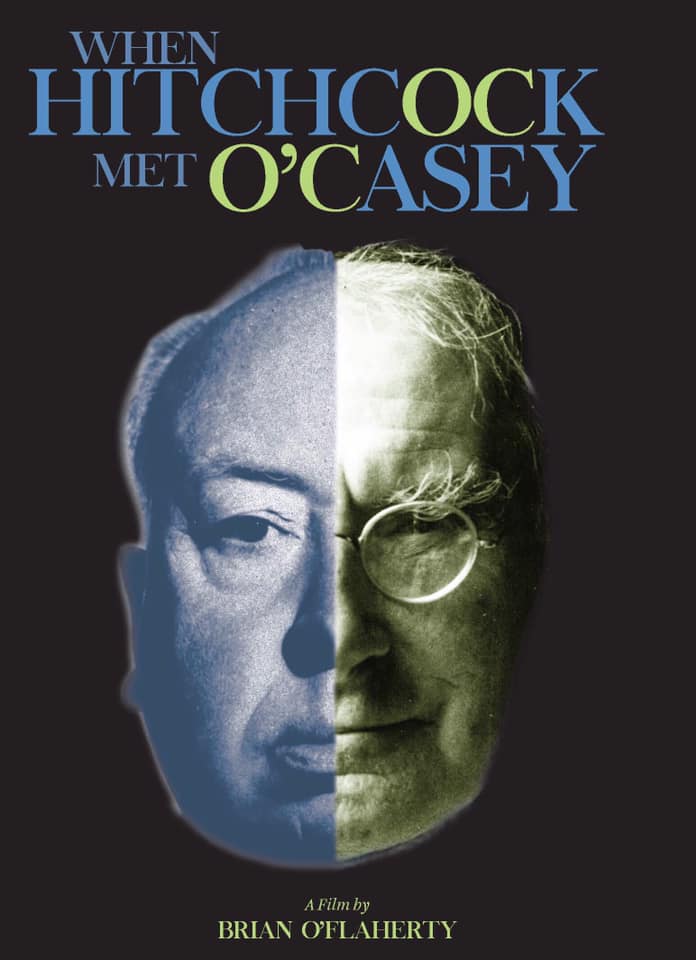

“When Hitchcock met O’Casey” DVD now available

This feature length documentary , made in conjunction with the East Wall History Group is now available on DVD .

This feature length documentary , made in conjunction with the East Wall History Group is now available on DVD .

It is currently available from the following outlets in Dublin , Galway and Kerry :

Tower Records ,

Golden Discs,

OMG @zhivago, Galway,

Easons,

Irish Film Institute,

Music Express, Killarney.

It is also available mail-order from Easons , with free postage :

Dec 15

![[Vallance & McGraths]](http://eastwallforall.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Valance-McGrath.jpg)