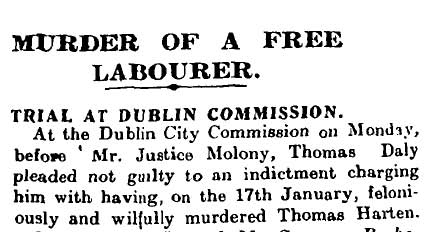

North Dock resident “not guilty “of 1914 murder

One hundred years ago , on the 7th April 1914 , a headline grabbing court case ended , with North Dock resident Tom Daly found not guilty of ‘wilful murder’ , but jailed for two assaults that occurred on the same evening. In a fascinating two part feature , Hugo McGuinness tells the story of the ‘blackguard’ Tom Daly , a dock worker , trade unionist and Irish Citizen Army volunteer. Part one tells his story up to the close of 1915 , and the concluding section will follow next week, on the 16th of April.

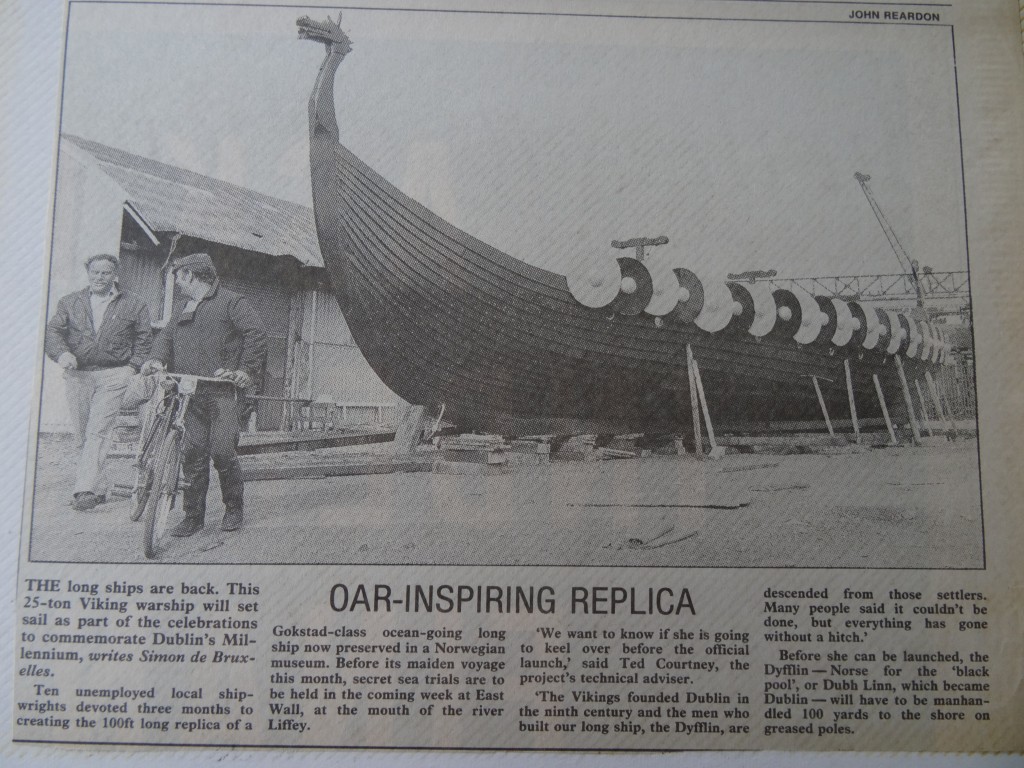

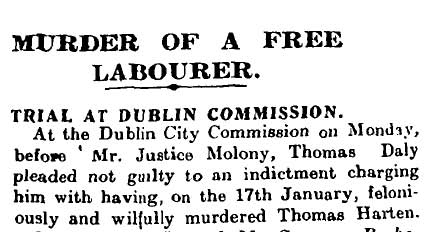

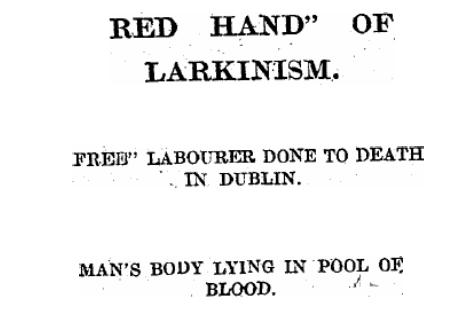

The 7th April 2014 sees the centenary of the verdict in a particularly vicious murder case which brought the Great Lockout to a close. The accused was Tom Daly , who lived his entire life in the North Dock and Inner City area. The victim, a 33 year old strike breaker or “Scab” from County Meath, had been brutally beaten to death on the 17th January 1914. The case was so shocking that it was widely reported throughout Ireland and Britain and filled up numerous column inches for months. One hundred years on and the non-compromising directness of the term Scab still hits home. In the black and white world of the 1913 Lockout there was no room for grey areas. James Larkin had caused outrage as editor of The Irish Worker after it declared – “When a man deserts from our ranks in time of war (for a strike is war between capital and labour) he on the same principle forfeits his life to us. If England is justified in shooting those who desert to the enemy, we are also justified in killing a scab”. Yet grey areas existed, and one such example was the victim, Thomas Harten from Carlinstown, who was working for Tedcastle McCormick Coal Factors in the Docklands area of Dublin.

Williamstown house, Co Meath, now abandoned.

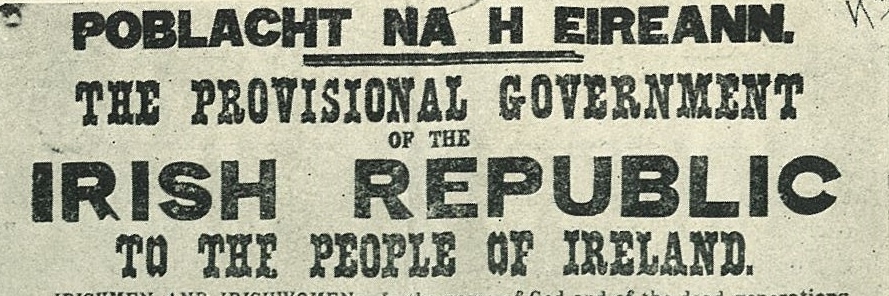

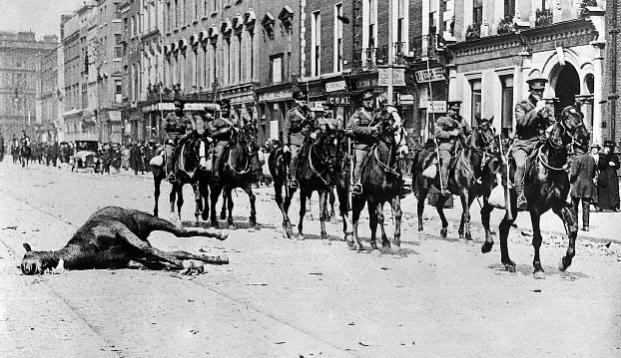

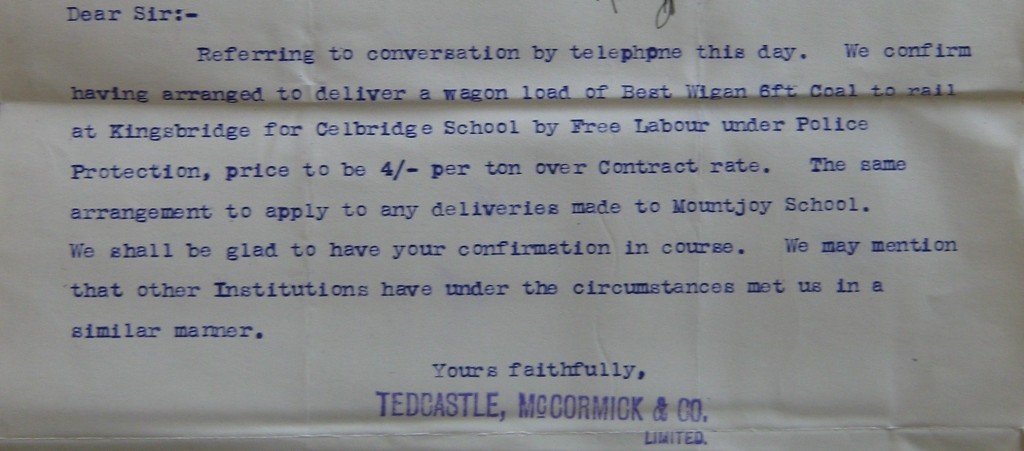

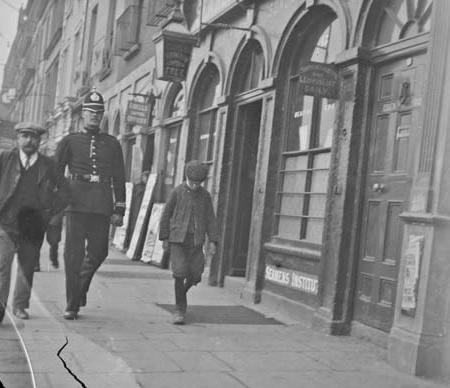

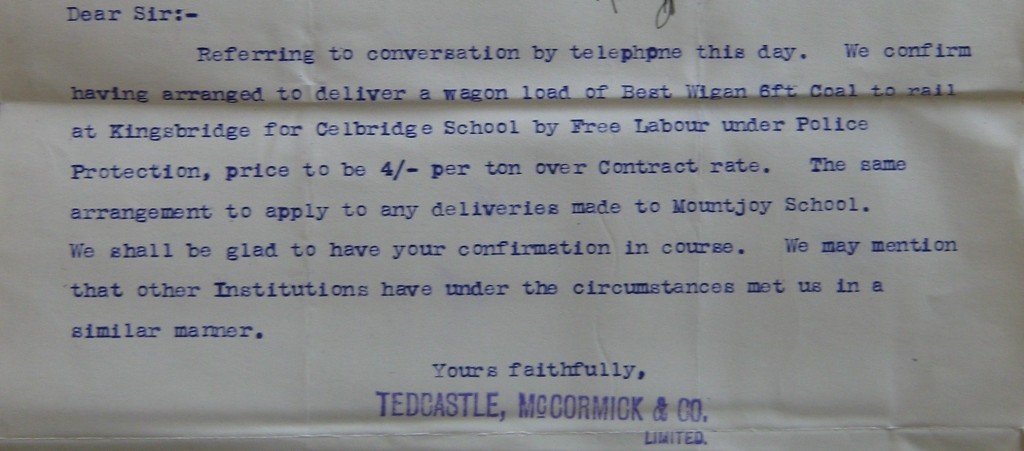

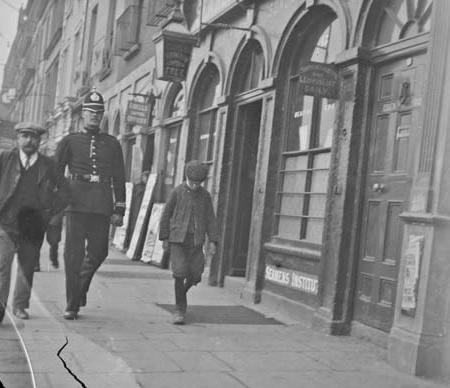

Harten’s background was recently traced by Meath Historian Danny Cusack. He was the eldest of 8 children born to Thomas and Mary Harten who made a subsistence living as herders and small scale tenant farmers. Census evidence suggests that like their city contemporaries, the Harten’s were rarely more than a missed rent-payment away from eviction. Cusack uncovered that Harten and his brother John were members of the Kilbeg branch of the United Irish League and had been part of a large meeting in Carlanstown in February 1912 which called for the break-up of the nearby Emlagh and Spandau estates and the land redistributed to tenant farmers. By 1913 his family were living and working at the Williamstown House Estate of Henry Mortimer Dyas, a noted horse-trainer, who was related by marriage to the McCormick’s of the Dublin coal company. During the great Lockout , the bitter struggle between employers and workers to break the Transport Union, large numbers of non-union or Free Labourers were imported from County Meath to fill the places of striking workers. Dyas conscripted local workmen to fill the ranks of the Dublin coal yards of his relatives. Tradition in the Harten family relates that Thomas’s parents were reluctant for him to go but fearing another eviction he felt he had no choice. It was to prove fatal. ( Letter below details the company raising prices of coal deliveries , and image is free labourers transporting coal under police protection).

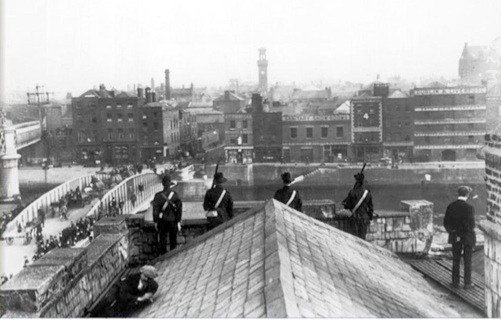

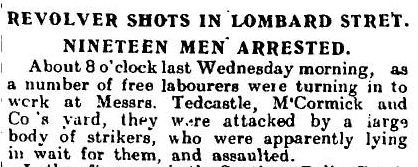

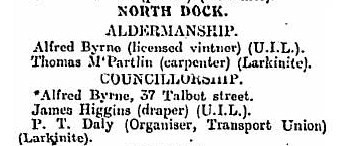

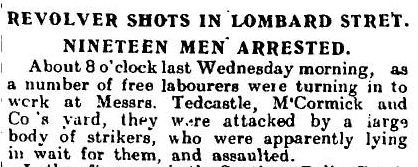

By the 16th January 1914 the great strike was on the verge of Collapse. Negotiations were underway in the Docklands which would see 5-600 strikers return to work at the shipping companies of the City of Dublin, the Silloth and Isle of Man, the Duke Company, and Messers Palgrave and Murphy. The carters at Pickford and Wallis would also return with 150 workers from the Port and Docks joining them. The British and Irish Shipping Company remained on strike as did Tedcastles, buoyed up with a plentiful supply of ‘Free Labour’ from County Meath . Tensions came to a head when a full scale riot broke out in Townsend Street on the morning of the 21st January when strikers clashed with up to 80 Scabs going to work at Tedcastles and shots were fired on the street. (Many free labourers were allowed carry guns , and often used them recklessly. Most notoriously , 16 year old Alice Brady was shot and later died , while the vice chairman of the Port and Docks Board was wounded). Seizing on the momentum of the previous months, the Labour Party, backed by the Trade Unions were putting forward candidates for the municipal elections to Dublin Corporation largely drawn from the ITGWU or the Dublin Trades Council. Meanwhile the Parliamentary Inquiry into the “Dublin Riots” which saw a number of people killed by the police was about to resume.

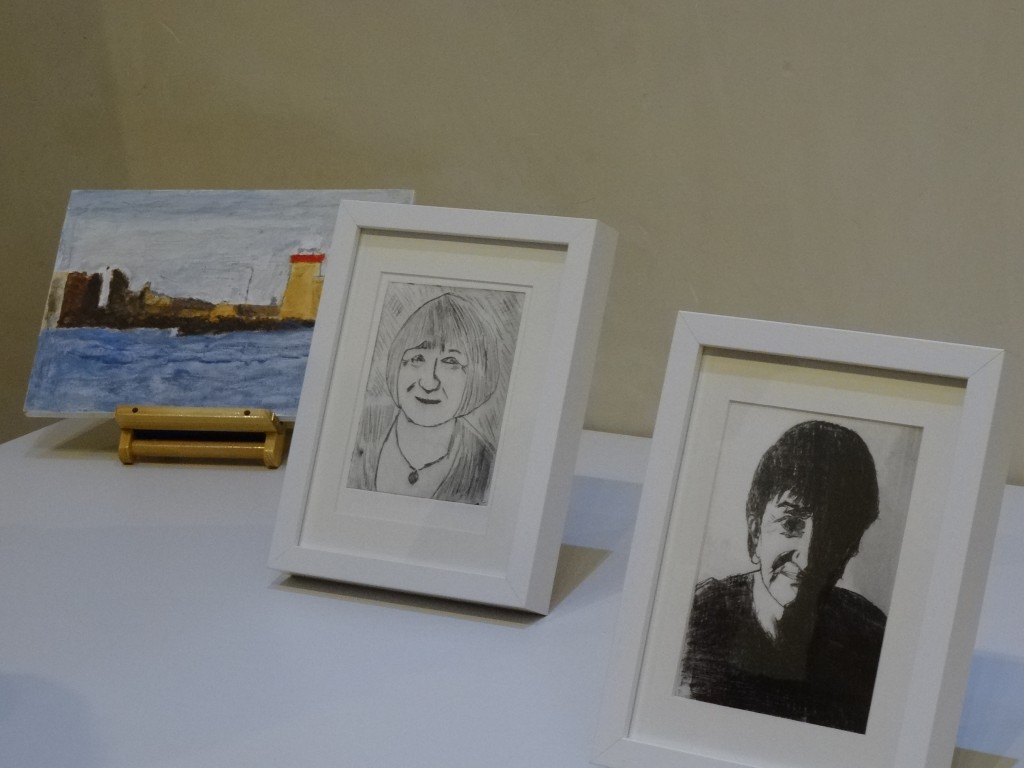

The injured George Maguire , court sketch

This was the background to the fatal Saturday when Thomas Harten and his friend George Maguire ( of Newrath, County Meath) left their accommodation at number 2 Beresford Place. This was “The Barracks” ,provided by the Employer’s Federation for strike breakers(which surprisingly was located directly across from Liberty Hall, headquarters of the striking workers). They walked across the city to the Tivoli Theatre, stopping briefly at Slevin’s, a gunsmith on Essex Quay, where they purchased revolvers and a dozen rounds of ammunition. About 9.00pm as they passed the Halfpenny Bridge they were attacked on Wellington Quay. Maguire was knocked unconscious but Harten managed to escape. His movements after that are unclear but around 10.30pm, while making his way back to “The Barracks”, he was accosted on Eden Quay by a group of men. He was knocked to the ground with a heavy weapon, repeatedly beaten, and one of the assailants delivered a fatal kick to his head,( which according to the doctor at the inquest it was “crushed like an eggshell”). He was left unconscious , with his clothes and the pavement covered in blood. The next time Maguire would see his friend was on a mortuary table in Jervis Street Hospital. They had been in Dublin 6 weeks. Within hours a man named Thomas Daly was arrested and charged with Wilful Murder. Shortly afterwards two others, James Morrissey and John Doyle, were also arrested and charged as accessories.

Court sketch showing Morrissey , Doyle and Daly.

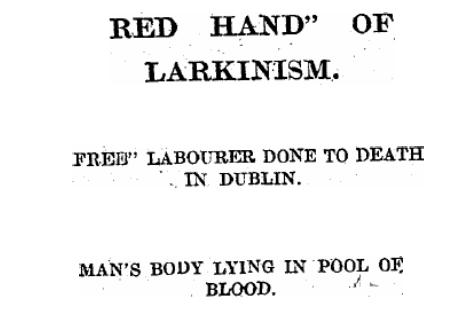

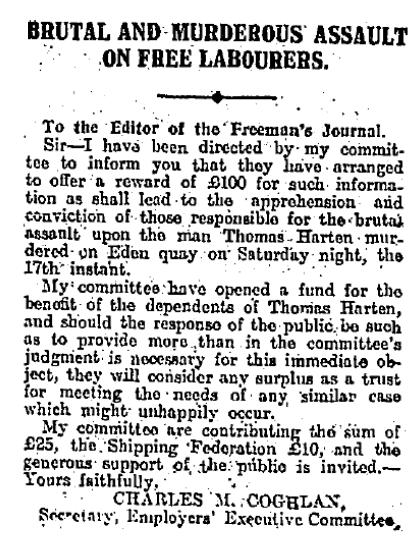

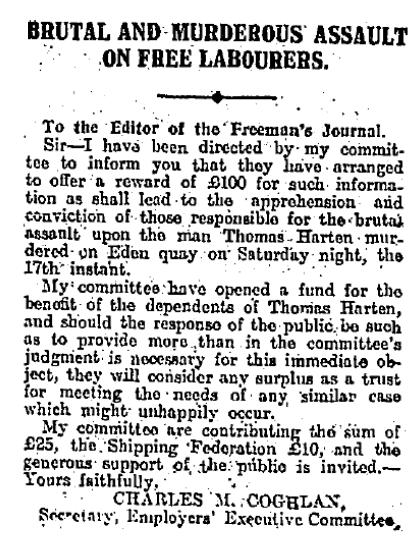

Over the following months at the Inquest and at his subsequent Court appearances Daly maintained a dignified presence and was firm in maintaining his innocence. He had freely admitted involvement in two other assaults on Scabs that evening. Most damningly, he was in possession of a revolver, which he claimed to have found in Tara Street and was believed to have been the one purchased by Harten earlier that day. It had all the appearances of an open and shut case. The Authorities wanted blood and were certain of the real culprit. Cork’s Southern Star Newspaper claimed it had all the hallmarks of “The Red Hand of Larkinism.” The Employers Federation offered a £100 reward for witnesses, while The Toiler, a pseudo labour Newspaper subsidized by William Martin Murphy, announced it was starting a subscription to raise funds for the Harten Family. They don’t appear to have met much success. The Employer’s Federation saw Larkinism as the cause of all their ills and Thomas Daly was to be their sacrificial lamb as they demanded their pound of flesh. Surprisingly little information was forthcoming about Thomas Daly in the newspapers which might have helped to explain why he was singled out by the authorities.

Thomas Daly was born at No. 47 Spring Garden Street in the North Strand on 15th January 1869. His Father Patrick was from County Meath and as a 25 year old was arrested for stealing cattle. According to family tradition he was sentenced to transportation but for some reason never reached Australia. Records show a Patrick Daly receiving 10 years transportation in 1851 but for some reason was released 4 years later having served his time in Ireland. Having married Elizabeth O’Shea they moved to Dublin where Patrick set up as a pork butcher at Spring Garden Street and it was here that Thomas and all his known siblings were born. Thomas married Rosanna Donnelly on the 8th July 1894 having returned from serving with the British Army in India and spent most of the rest of his working life in the North Docks or North Inner City area in slightly better quality houses than most of his contemporaries. Not surprisingly the 5 children recorded as being born to the Daly’s in the 1911 Census were all still living.

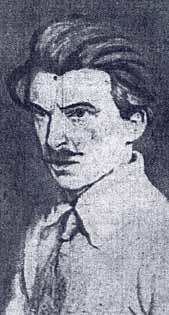

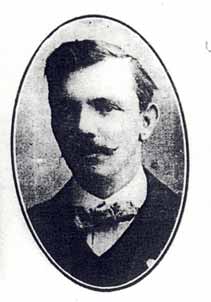

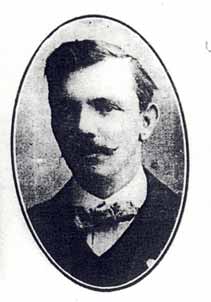

Tom Daly , Court Sketch

He had joined the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, serving for some years in the Indian subcontinent He later transferred to the Reserve, Dublin City Company, in which he served up to 1911. At the same time he was working for the shipping company of Michael Murphy, earning a good living of between 30-35 shillings a week. His army reserve status would bring in another 6-7 shillings a week, which, in comparison with his contemporaries made him relatively well off. Laurence Healy, a Stevedore at Murphy’s, stated during Daly’s trial that in the 30 years he had known him he was “a steady, sober, hardworking man,” who rarely drank and whose only absence from work was due to call ups to the Artillery Reserve for training.

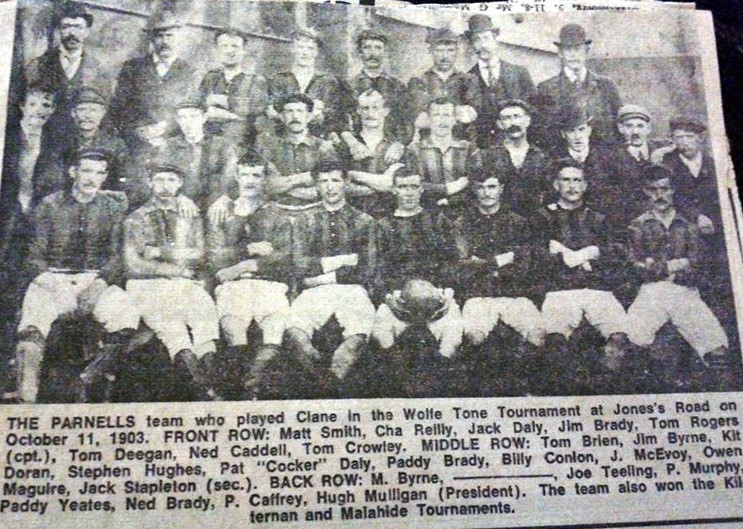

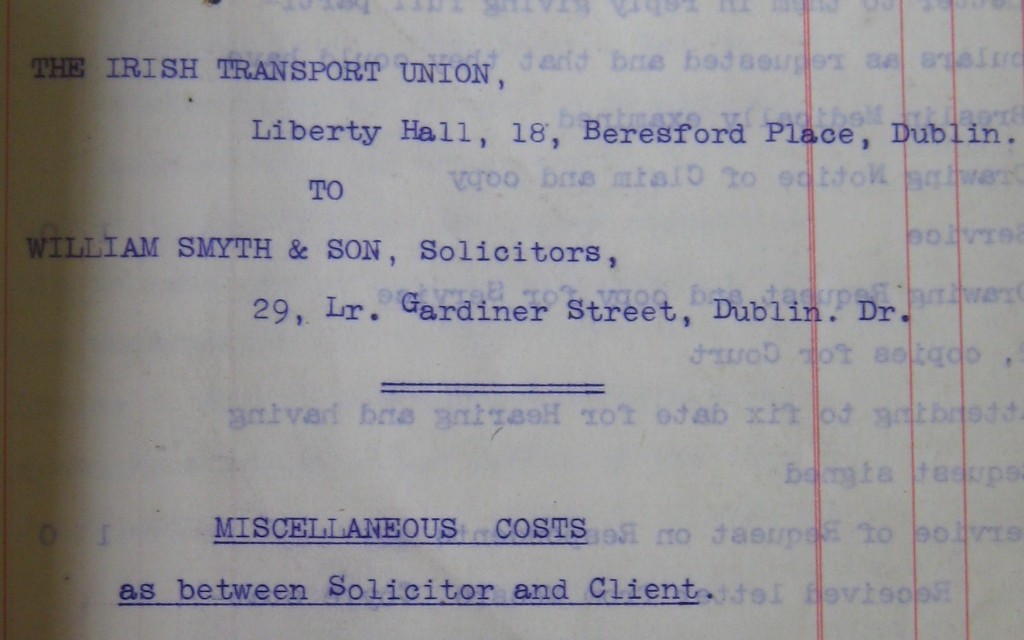

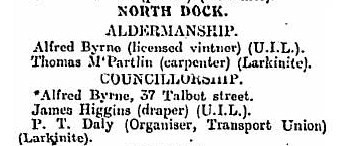

By 1901 Daly and his family were living at No. 20 Coady’s Cottages , later moving to a two room house at No.2 Toole’s Cottages off Newfoundland Street. Daly was on the 1908 electoral rolls for the area,( possibly a product of a general politicising of the North Dock by the socialists Walter Carpenter and Edwin Halpin at the beginning of the century). In 1911, the year he retired from the Artillery Reserve, he joined the Irish Transport and General Workers Union(I.T.G.W.U.) on 11th January. He subsequently moved to the Dublin Steamship Company where he was employed as a Coal Labourer when the 1913 Strike broke out. That year he also became a member of the recently formed Citizen Army. Daly had probably acted as one of the Union’s Dockland Enforcers during the strike, and possibly worked as part of the electoral team of P.T. Daly, a candidate in the North Docks Ward in the municipal election held in January 1914.

P.T. Daly was powerful organizer with the ITGWU, a leading member of the Dublin Trades Council, and for some years a councillor on Dublin Corporation.

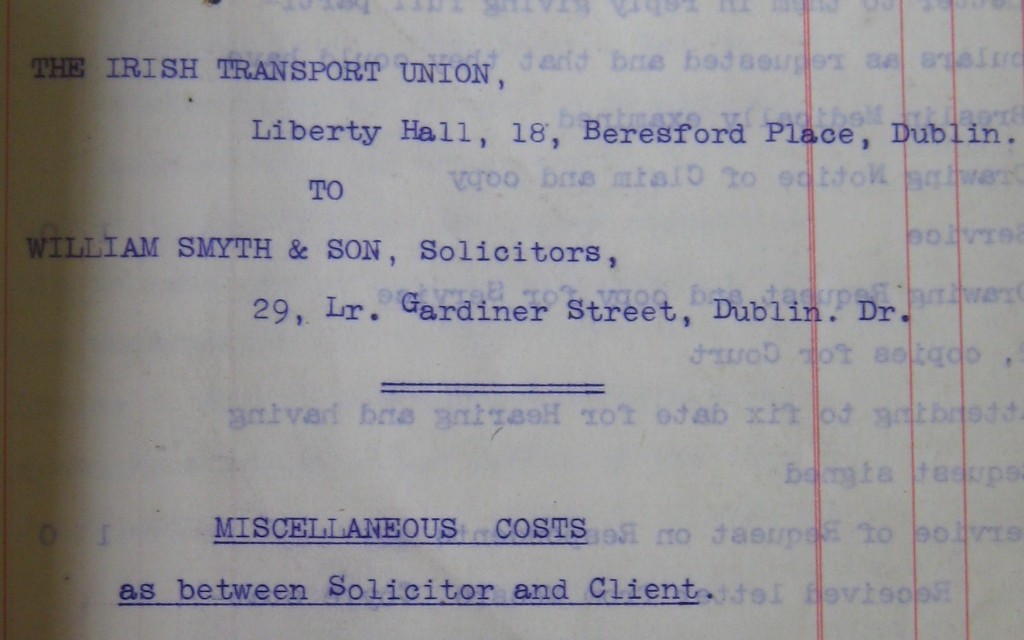

P.T. instructed Smyths, the Transport Union’s solicitors, to take up Thomas Daly’s defence. (This was the legal firm which had acted for the Union representing the Merchants Road families evicted in December 1913).

By the 7th February the Crown had found a key witness in Patrick Doyle, a 21 year old deaf-mute, who picked out Daly from a number of line-ups. On investigation Smyths discovered that not only could Doyle speak, but he had several aliases such as Arthur Thoms, Arthur Baxendale, and Arthur Cunningham. Under the latter name they found he had been dishonourably discharge from the army for being of “bad character.” When confronted with this at the hearing at the Police Courts he broke down and admitted he was a Londoner and had come to Dublin to Scab. He claimed he posed as a deaf-mute to disguise his accent which would have exposed him as a Free Labourer to the strikers. The case then turned to farce, when, following Daly’s Hearing, Doyle( alias Baxendale alias Cunningham) was immediately tried, in the same court, for the theft of a handbag containing 10 shillings and sentenced to 2 months in Mountjoy. Smyths had uncovered a history of at least 4 previous convictions Doyle had received for larceny. It appears Doyle (alias Baxendale alias Cunningham) had been made aware of the £100 reward and facing a jail sentence for theft was persuaded to lie about Thomas Daly. Desperately he even claimed that Harten had died with his face towards Liberty Hall and his feet pointing towards the Liffey as if providing a clue to his assailants. Smyths had also written to the Prison Board for character references on 13 other witnesses the Crown intended to bring against Daly. They request was refused as “there was no precedent.” But the point was made. The Transport Union would use all their resources to defend one of their members.

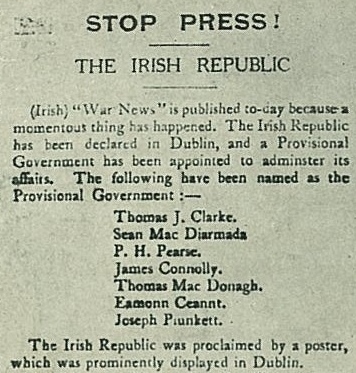

Tom Daly was finally brought forward for trial by the City Commission at Green Street Court House at the end of March. James K. O’Connor, the Barrister instructed by Smyths, pointed out that despite the great loss of blood by Harten, none was found on Daly’s Clothes. Several witnesses who saw the fatal assault on Eden Quay failed to identify him in Court, giving descriptions which totally contradicted Tom Daly’s appearance. George Maguire also failed to identify any of his assailants in the earlier attack and it came out that the assaults on the two Scabs by Daly occurred about 10 minutes after the fatal blow was delivered to Thomas Harten on Eden Quay. O’Connor pointed out that the instinctive thing to do in such a case would be to dispose of the revolver – not pick it up and put it in your pocket. In his summing up on the 7th April 1914, the Judge, Justice Molony, virtually instructed the jury to find Daly innocent. Tom Daly was found not guilty ,but he was immediately brought forward on the other two assaults , found guilty, and sentenced to 2 years hard labour. The case against Doyle and Morrissey was dropped.

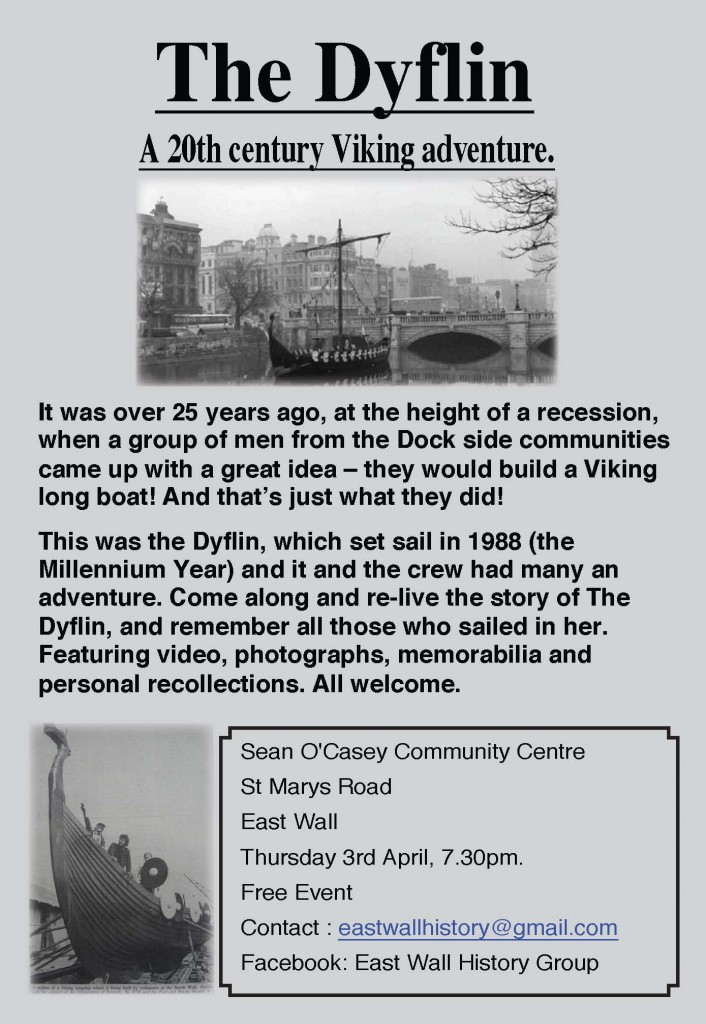

Arthur Henderson

The Daily Herald (a London published socialist newspaper) gave a good summary of the case.

“Having failed to establish their case against Thomas Daly, a Dublin worker, for the murder of Harten the Blackleg, the Crown wisely dropped the prosecution against the two other men whom they had arrested on this charge, against whom the evidence was even flimsier than that against Daly. But, in the characteristic fashion of the law, revenge was nevertheless wreaked on Thomas Daly for the police’s inability to hang him. In addition to the murder charge he was charged with assaults on two other blacklegs, and to these minor charges he pleaded guilty. For those two assaults Judge Molony inflicted on him the monstrous sentence of two years hard labour, saying, at the same time, that he feared he was not doing his duty in not sending him to penal servitude!”

The Herald went on to point out that “the scab who shot Alice Brady got no punishment and that the policeman identified by two witnesses as having murdered Nolan have never even been put on trial“. On the 21st April, Arthur Henderson, Chief Whip and future Leader of the Labour Party in Britain, asked in parliament, whether, “in view of Daly’s admission of guilt and the ordeal he had been through for the previous four months a remission of his sentence might not be possible?” Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, replied “the exercise of the prerogative of mercy is a matter entirely for the Lord Lieutenant, who I am sure will consider carefully any representations made to him on behalf of the prisoner.”

PT Daly

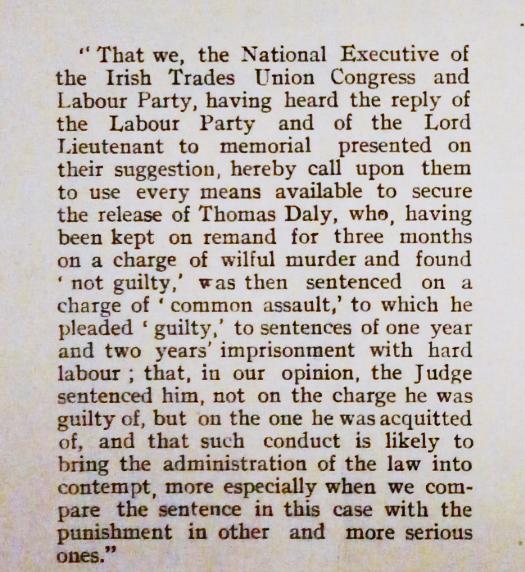

P.T. Daly instructed Smyths to petition the Lord Lieutenant on the 11th June. The reply came back that “justice must take it’s course.” He then had a resolution passed by the Dublin Trades Council to the effect that

“the Judge sentenced him (Thomas Daly), not on the charge he was guilty of, but on the one he was acquitted of, and that such conduct is likely to bring the administration of the law into contempt, more especially when we consider the sentence in this case with the punishment in other more serious ones.”

Queried on this P.T. Daly explained that a previous case involving the rape of a 7 year old girl by a Free Labourer named Madden alias Maddox had been dropped by the Crown and Maddox freed, according to the Court’s Recorder, on the basis that no real harm had been done to the child. The fact that she had contracted “a loathsome disease” from Madden/Maddox was not taken into account. Daly went on “comparison of the treatment of the Free Labourer and the Trade Unionist justifies the resolution in my mind.”

Momentum was maintained in Labour circles with the Daily Herald reporting on the 8th August “Thomas Daly is still in Mountjoy undergoing the monstrous sentence of two years hard labour for assaulting a non-Unionist. He must be set free at once.” Charles Duncan, Labour MP for Barrow-in-Furnace, and Secretary of the Workers Union founded by Thomas Mann in 1898, helped to maintain the pressure arguing that Thomas Daly had never been in trouble before and was known to be a good father and husband. He pointed out that “in view of the feelings of the time a sentence of two years does not appear to be tempered with mercy.“

Unfortunately the records showing Tom Daly’s release date no longer survive. What is certain is that the campaign must have had an effect as he was out of prison and working on the staff of the Transport Union towards the end of 1915.

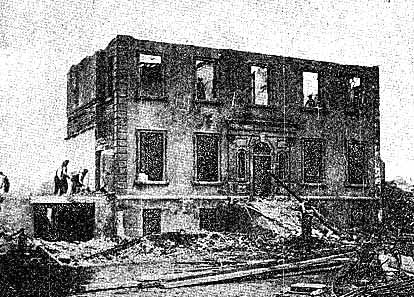

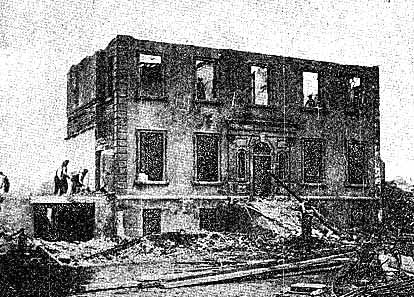

Demolition of Croydon House 1930′s

Virtually unemployable due to the high profile nature of the murder trial, Daly was found a position as an agricultural worker at Croydon Park, the workers pleasure grounds founded by James Larkin. Although best known for it’s sporting events, concerts, and as the location of the Citizen Army’s training manoeuvres and displays, Croydon Park, during the tenure of Captain James Stavely in the 1880s, had developed an international reputation for the quality of it’s agricultural produce, and this was still an important revenue stream during the ownership of the Transport Union.

Tom immediately threw himself back into the activities of the Citizen Army.

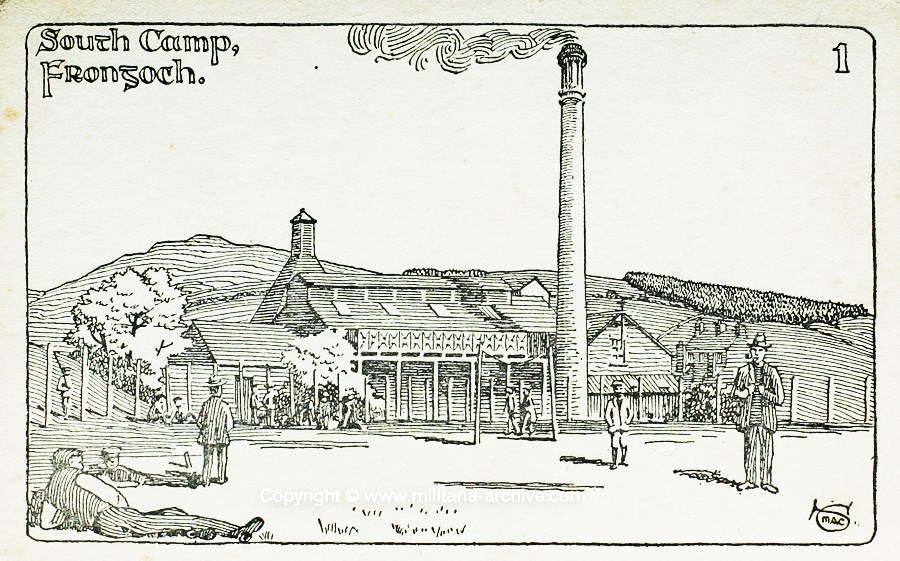

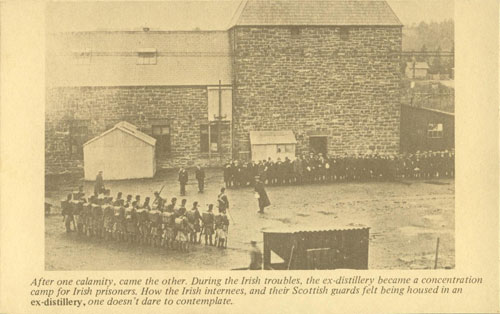

And it is here we end part one of our story of ‘Blackguard ‘ Daly. In the second section, to be published on 16th April , we will cover his eventful career in the Irish Citizen Army ( where he was the subject of its first Court Martial under James Connolly and fought in the City Hall Garrison during the 1916 Rising) , his internment in Frongoch (where he led a strike against forced labour and also endured a heart breaking family tragedy) and we will reveal the origin of the ‘Blackguard’ nick-name .

Since the original publication of this feature we have updated some sections. We would particularly like to thank Dario Reggazzi for information on his Great Grand-Uncle and the history of other members of the Daly Family.

For clarifications , corrections , further information or other comments please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Photo credits – The majority of images were sourced by Hugo McGuinness . The Coal company letter courtesy East Wall History Group , Coadys Cottages courtesy the Paddy Curtis Collection, Quays courtesy Dublin Dockworkers Preservation Society.