Oct 03

“The Fighting Old Guard” : The O’Doherty family in the North Dock

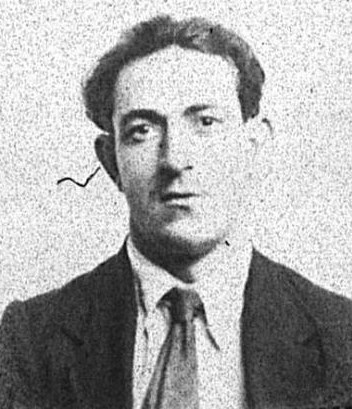

“One of the cheeriest men in the ward, and one of the most particular as to the set of his hair.”

During the 1916 Rebellion Michael O’Doherty of the Irish Citizen Army was wounded 12 times – 1 bullet hit his right eye; 2 his left arm; 1 his left jaw; 1 the left side of his head; 4 in his right arm; 1 in his right cheek; and 2 in his left arm . Despite his catastrophic injuries he survived, only to pass away just over three years later due his injuries and subsequent treatment. But the story of Michael O’Doherty and his family, does not begin, or indeed end with these events. The family had a record of trade union and political activism in the Docks dating back to the 1890’s, and for years after Michael’s death his family battled to have his Easter Rising participation properly recognised. This is their story:

The O’Doherty’s wore their politics on their sleeves. At a time when it was rare for the Gaelic “O” or “Mac” to be used Michael O’Doherty (senior) used it proudly when he married Margaret McCann in Ballymoney, Co. Antrim, in 1877. Throughout his life he would fight off attempts by well meaning Parish Priests to anglicise his children’s names in the belief that it might give them some advantage in life. The Land question dominated local politics in Antrim throughout the 1870s and Ballymoney Town Hall was the center of activities hosting many meetings and events relating to tenants rights. The O’Dohertys were farming people but Michael senior received a good education and was trained as a Law Clerk. Family tradition suggests Michael senior was politically involved at this time and was probably engaged in agitation for tenants rights. Michael junior was born here in 1879 however it seems his parents had to follow the time honored emigration route and moved to Scotland shortly after his birth. Family lore suggests it may have been due to their political activities. Not surprisingly some thought he was born in the Scottish Industrial heartland of Glasgow. While it’s unclear exactly what Michael senior’s politics were at this time, one tradition being an involvement with the IRB, according to his daughter Lilly, Michael junior, through his father’s influence, was “associated with Republican activities from boyhood.”

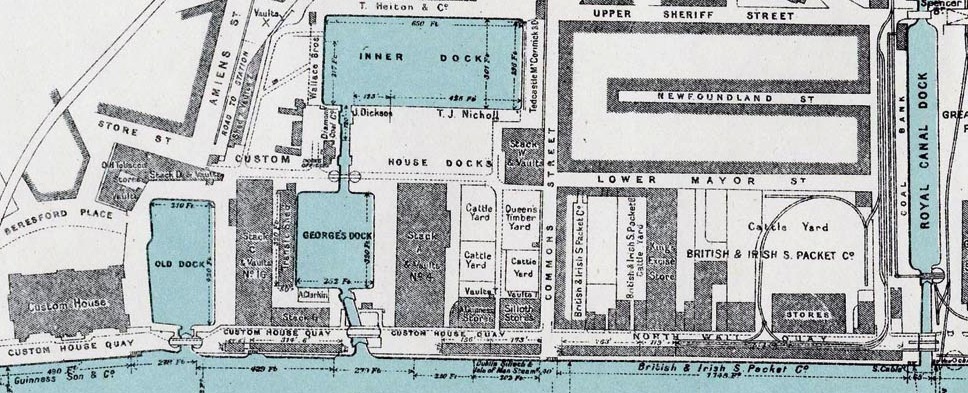

By the mid-1880s the family were living in Ballybough at 19 Forster Terrace with Michael Senior working as a law clerk to support his growing family. By 1891 they had moved to Seville Place just as labour problems were about to break out in the Docklands. The Merchants Protection Association had erected steam winches on the docks which alarmed the corn porters who saw the machinery as putting many of their fellow workers out of a job. It soon became apparent that the MPA intended using the situation to change employment conditions, break the various unions who represented the workers, and employ free or non-unionized laborers at whatever rates they saw fit. The members of the MPA had combined with the British Shipping Federation to break the unions and had placed a Mr. Hunter of the Shipping Federation in charge of the unloading of all grain-ships. Hunter had imported laborers from Cork and Belfast who were non-union members and working below the agreed Dublin rates. In June the Dublin grain-workers went on strike with action quickly spreading to the carters and even the ships firemen. Soon over 800 men were out.

Large numbers of police were drafted into the docklands to protect the MPA workers as they unloaded various ships cargoes. By the 8th July the Freeman’s Journal was predicting an “all out Labour War.” Soon the workers of The Grand Canal Company and Gas Workers Union had joined them in sympathy with various other trade societies in Dublin promising financial support. At a meeting of the Trades Council on the 8th July the President called on the men to take “an active part in the struggle” and make their presence felt on the quays. He also noted that while the men might not be paid “their wives and children would be kept with bread and butter in their mouths.” More Free Laborers had been drafted in with the Merchant’s Warehousing Company finding a plentiful supply of country agricultural workers while one Belfast Merchant shipped in his own hands to unload his cargo. While the various speakers called for peaceful protests on the docks, P.A. Tyrrell of the Amalgamated Engineers Society reminded them, that “any man who helped the Merchants in this fight, no matter to what trade he belonged, whether he belonged to his trade or not, was a scab of an unmistakable type, and the name would never leave him.”

Two days later Charles M’Keever, a corn porter working for the corn merchants Brown and Gilmer, was driving a cart down Seville Place accompanied by a number of Shipping Federation employees. E. Donnelly, the corn porters union representative, lived at No. 50, and large crowds of women, children, and striking workers congregated outside his house. Noticing M’Keever the crowd began to chant “Scab!”, and throw stones and other missiles at him. Watching nearby was Michael O’Doherty senior, who given his occupation and what was about to happen, was possibly giving legal advice to Donnelly in relation to the strike. M’Keever went to his lodgings to find the windows smashed and the landlady promptly asked him to leave her house. At this point he was assaulted, kicked to the ground, and cut on the hands a number of times with a knife. The crowd then turned on Cahill and Storey, the Shipping Federation men, who subsequently left Dublin and returned to the countryside.

Of the two hundred people involved in the incident, only one, Michael O’Doherty senior, was arrested and indicted for assault with grievous bodily harm of the three men and Constable 109C who attempted to break up the row. M’Keever admitted to having previously seen O’Doherty on a number of occasions, suggesting he was engaged in organising the workers, and which might explain why he was singled out. Several witnesses claimed O’Doherty “took no part” in the affair and ultimately he was acquitted of the assault but was then charged with obstructing the Police in their duty. O’Doherty was sentenced to six week in jail.

The strike ended later that month but flared up again in August. As financial support fell away things reached an inevitable conclusion by mid-November when the strikers conceded the right of the MPA to use steam winches to unload cargos; they agreed to work with whoever the MPA chose to employ whether Free Labourers or otherwise; they agreed to a pay-freeze for at least twelve months. They also accepted that they would be re-employed at the discretion of their employers many of whom were intent on fulfilling the engagements of their imported workers. Facing financial ruin their Trade Union collapsed. The jail sentence seriously effected Michael senior’s health and by the turn of the century much of the burden of supporting the family fell on Michael junior. The British shipping Federation was invited to set up offices in Dublin.

The family moved to No. 10 Mayor Street just as a revival of Gaelic Games was taking place. Michael junior seems to have taken a great interest in the sport but it would appear his role was as more of an organiser than as a player. By 1895 teams such as Rovers (Sheriff Street), Charleville (North Strand), Hawthorns (East Wall) and Saint Laurence O’Toole’s were all making names for themselves in the local leagues. Michael Junior was coming into contact with people like James Nowlan and Dan McCarthy who would become life-long friends, the latter, the first Dublin born President of the GAA, fought in the 1916 Rising, and served as a Sinn Fein TD between 1920 – ’24. O’Toole’s in particular were deeply nationalistic with 51 members of the Club taking part in the Rising. They shared headquarters with the local Gaelic League Branch at 100 Seville Place, and their pipe band had Tom Clarke as it’s president and Sean O’Casey as it’s secretary. O’Doherty’s younger brother Patrick Joseph shared his enthusiasm, so much so, that a spur of the moment decision in May 1905 would have serious repercussions. Patrick Joseph was working as a Docker when on the 14th May 1905 he was unloading goods at the London and North Western Railways warehouse at the North Wall with a neighbor, James O’Reilly from Spencer Street. O’Reilly worked for the company, and examining the inventory, mentioned that there was a consignment of football bladders in the warehouse. They liberated three of them unaware that their actions were noticed by a Detective employed by the railway company. Both received 14 days in Kilmainham for their efforts.

Michael O’Doherty worked for Wordies an extensive carriage and storage company with premises in Beresford Place and East Wall in Dublin. They also had numerous branches throughout the country. Initially he worked in their warehouse and later transferred to the carters section earning £2.10.0 per week much of which went to supporting the family as his fathers health deteriorated. He took a keen interest in politics, both he and his father being on the electoral rolls for the North Dock Ward, when few had the property qualifications necessary. A revolution was on the way in Ireland and O’Doherty, as his Irish Citizen Army (ICA) colleagues would record, did “not shirk his duty when it came to the test.” 1908 saw the entry of James Larkin into Irish Labour affairs. Initially representing the British NDLU, Larkin had arrived like a whirlwind, agitated on behalf of Irish workers, and quickly found that his union had little interest in their Irish members problems. Suspended by the British Executive, Larkin went on to found his own Irish union on the 29th December that year. One of the first members of the No 1 Branch of the ITGWU was Michael O’Doherty junior.

By 1910, Michael’s younger brother Constantine, having completed his apprenticeship as a pork butcher, had set up in business in Belfast with his young family. Michael is recorded in the 1911 census as living there in his younger brother’s house in Salina Street a short distance from the Belfast branch of Wordies at Divis Street. At first glance it seems a strange move. Ellet Elmes, a protestant and O’Doherty’s future colleague in the Citizen Army, moved to Belfast at much the same time to work in Harland and Wolfe shipyard. Elmes found the deep-rooted sectarianism too difficult to stomach and returned fairly quickly to Dublin. Most dockworkers in Belfast were members of the British NDLU. However, in 1910 P.T. Daly had brought members of the Belfast deep-sea dockers into the ITGWU. In May 1911 James Connolly arrived in Belfast as Branch Secretary and Ulster Organizer setting up union offices at 112 Corporation Street. By July 1911 he had 300 dockers out on strike in sympathy with the Seamen and Firemen’s Union. Nightly meetings were held on the steps of Belfast Customs House on one occasion organizing a demonstration using a coffin inscribed with “Shipping Federation” which were attempting to break the strike. The strike turned nasty but eventually the employers offered to recognize the ITGWU and offer an increase of 1 shilling a day. It seems likely that Michael O’Doherty with his skill at organizing and his Ulster background was one of a number of activists such as Ellet Elmes sent up to assist Connolly to establish the union in Belfast.

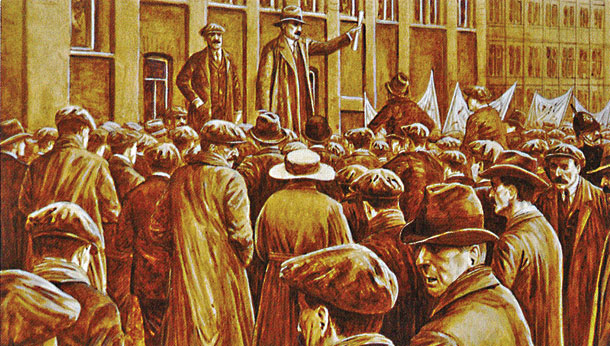

O’Doherty was back in Dublin by 1913. On the 31st July he led over 300 workers from Wordies out in sympathy with the great strike then in progress. Information obtained by the National Graves Association stated that he “took an active part in the 1913 Lockout“, while Jim Larkin called him one “of the fighting old guard of the Transport Union.” Labour News in 1936 recalled that on the formation of the Citizen Army O’Doherty joined up to “defend the workers from the batons of the police during the great lockout.” The strike cost him his job but he quickly found employment at Wallis & Co who described him as a “sober, industrious, and willing worker.“ He continued to throw himself into Citizen army business.

Michael O’Doherty spent most of April 1916 on guard duty at Liberty Hall in preparation for the Rising. On the 24th April he was part of the group which marched from there, under Michael Mallin, to Stephens Green. He was one of a party of four who raised the Tricolor flag above the roof of the college and as he was a good shot, O’Doherty remained on the roof of the College of Surgeons tasked with operating as a sniper if they came under attack. ICA man James O’Shea was also placed on the roof on Tuesday 25th April when the British attack was launched from the Shelbourne Hotel. He recalled it as “hot and heavy” being “unable to stand up under any circumstances.” Bullets chipped away at the masonry and O’Shea was impressed by the ability of the opposing marksman. He had emptied his clip and was about to reload when a colleague tapped him on the shoulder and pointed to a figure on the right. There was Michael O’Doherty casually eating a sandwich as if he were on a picnic. O’Shea tried to shout at him to take cover but before he got the words out he saw the bullets from a machine gun burst rip into O’Doherty and as O’Shea remember it “his face was gone”. Countess Markievicz described him as being “deluged with shrapnel.” As O’Doherty slumped over the parapet of the roof blood flowed onto a white blanket below shocking and freezing his comrades. Joe Connolly, a future Fire Chief of Dublin, bravely raced from the green across to the college and up onto the roof. Together with David O’Leary, who had come over from London for the Rising, they managed to bring O’Doherty down before he could be hit again.

Madeline fFrench Mullen was there when he was lowered and described his as being in “a mangled condition.” It was probably because of Joe Connolly, a serving fireman as well as a member of the ICA, that the Fire Brigade ambulance came for O’Doherty just after midnight and brought him the short distance to Mercer’s Hospital. Two hours later they had to retreat in their attempts to take the body of James Corcoran from the green due to the continuous crossfire. It almost certainly saved O’Doherty’s life. Frank Robbins who opened the door for the crew taking O’Doherty out on a stretcher, noticing the amount of blood he has lost, whispered “you’re a gonner and the Lord have mercy on you.”

O’Doherty had been wounded 12 times. 1 bullet hit his right eye; 2 his left arm; 1 his left jaw; 1 the left side of his head; 4 in his right arm; 1 in his right cheek; and 2 in his left arm. After 4 days he was arrested at Mercers and taken to the hospital at Dublin Castle. A VAD nurse who treated O’Doherty, having heard “half his face was gone” and looking at his blood soaked bandages, prayed constantly that he might die to relieve his suffering. However a week later, she found out that his “face though frightfully disfigured, had not been blown away” and having made a recovery, she wrote that he became “one of the cheeriest men in the ward, and one of the most particular as to the set of his hair.” O’Doherty was in a bed next to Cathal Brugha who had been shot over 25 times so they had much in common. Another of their nurses held a commission in the UVF and was forthright in what her “boys” would have done to the Rebels had they got the chance. Yet when medical attention was needed she was a thorough professional impressing the Citizen Army and Volunteer patients with her kindness, attention, and skill. In an autograph album collected by a visitor to the Hospital, O’Doherty wrote “sure the great God never planned, for slumbering slaves a house so grand” in recognition of his treatment by the British army medical staff. He also noted that despite his horrific injuries he was “still not downhearted.” One day a soldier of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers came into their ward and putting a bag of fruit on Brugha’s bed, said “thanks!”, then turned around and walked out, to all the patients astonishment.

After three months in hospital Michael was sent to Knutsford Prison and later the detention camp at Frongoch. He’d lost an eye and an ear and the use of his left hand. The military guards at Frongoch tried to make fun of O’Doherty’s disfigurement. His reply was “see that eye and this hand – while I have one eye and one hand to fight with, no one will ever stop me fighting for Ireland.” Released from Frongoch in December 1916 O’Doherty initially rejoined his ICA colleagues. Kathleen Lynn organised to have him fitted with a glass eye but according to Countess Markievicz “the hardships and unsanitary conditions of the camp were more that his shattered body could resist and he just grew thinner and weaker.” O’Doherty made light of it and rarely complained. He was unable to work because of his disability and by 1918 had vanished from both Labour and ICA circles. Things were moving fast and according to Markievicz “in the rush of events no one had taken the time to find out where he was or what he was doing.” He was dieing, “dieing slowly from the effects of his treatment at the enemy’s hands”

O’Doherty passed away on the 22nd December 1919. His funeral was large and Countess Markievicz who attended has left a moving record of the events.

“So we his comrades in the fight, gathered to pay our last tribute and respect to a brave soldier and a loyal comrade. He lay so thin and tall in his brown habit with the crucifix in his curled hands and we thought how it softened death for him and for us all. … The atmosphere in the little house was electric with one thought, that he who lay there was true to Ireland, you heard it on every lip. His old mother sobbed out how Mickey had died a true martyr for Ireland, but how sorry he was to go before the fight was over and soon, sisters, brothers, friends, all paid the same tribute. He was a true Irish soldier and to Ireland he had given his life.

After a while his comrades placed him in the coffin and it was borne to Saint Laurence O’Toole’s Church as he would have wished, his soldier comrades marching behind him, taking turns to carry the coffin on their shoulders. His coffin was covered in the tricolor flag that he loved and under which he fought; behind him marched a piper playing an Irish hero’s funeral march on the bagpipes and … marching in military order were the Irish Citizen Army guarding him. He went to his last rest in the way he would have wished, a soldiers way, in spite of England’s armies, her tanks, and her machine guns.”

In the death notice placed in the Freemans Journal on the 23rd December 1919 Michael is described as “Irish citizen Army 1916.” For nearly two decades afterwards the family placed memorial notices in the papers on his anniversary which recorded his role during Easter Week. However, according to the family a well-meaning Doctor Dolan from Amiens Street, who treated Michael before his death, anxious that they should avoid any repercussions from the British military, had given the cause of death as stomach cancer. On 29th November 1919, Johnny Barton, the notorious Detective Sergeant of G Division, of the DMP, had been shot dead by The Squad. An attempted ambush on Sir John French, Lord Lieutenant and Chief of the army in Ireland had been carried out near Ashtown on the 19th December. According to family tradition the DMP made several visits to the O’Doherty home at this time and it was believed that their house was being watched. O’Doherty’s ICA comrades called on the family to have a military style funeral, such as had been given to ICA Stephen’s Green veterans Bernard Courtney in March 1917 and John Byrne in June 1918. Both had been large spectaculars, Courtney’s funeral touring the sites of the city where he had fought while Byrne’s consisted of four companies of the ICA marching from St Laurence O’Toole’s Church to Glasnevin. Lilly O’Doherty claimed that they were anxious “for the safety of the poor boys and did not wish to have any publicity” as times were “far from quiet.” Doctor Dolan, in keeping with the families wishes, had, according to Lily, left gunshot wounds off the death certificate. It was also for this reason that Michael was buried in the family plot at Glasnevin rather than in the Republican Plot as many of his comrades wished.

With the advent of the 1923 Pensions Act Michael senior applied on behalf of the family for a pension in recognition of his sons service . In doing so he had been upfront in admitting that the Irish National Aid Association had given them a grant in 1917 of £400 in acknowledgement that he “was the sole support of his family.” At that time Dr. Matthew Russell, who examined Michael, claimed that the wounds were so severe that he would be disabled for life. They also admitted that part of the aid money left to Joseph, Michael’s disabled younger brother, had been used to buy a grocers shop at No. 1 Mayor Street. The application was rejected on the basis that death happened outside the three years limit laid down under the 1923 Military Service Pensions Act. The family made appeals, to no avail, however by 1924 questions were being asked the result of which was an extension of the period of death allowed from three to four years after being injured which brought Michael O’Doherty’s case within the remit of the amended act in 1927. Once more Michael O’Doherty applied and again he was rejected on the basis of the death certificate provided by Dr. Dolan. The official verdict given on the 28th February 1928 was “your son’s death was not attributed to service.”

The O’Doherty family opposed the Treaty and according to tradition a number of Michael’s sisters were in Cumann na mBan. On the 1st November 1923 Michael senior was in the shop at No. 1 Mayor Street when he saw 6 men walking to his houses at No. 10. Following them he found their leader, a former CID man named William Kean inside the house threatening his son Joseph. Michael identified himself and then he asked them if they were CID and what their authority was. Keane produced a pistol and stated that it was his authority and “if you don’t shut up I’ll put the contents into you.” It appears they were looking for someone they believed was in the house but not finding him they left. Michael followed them to Guild Street where he found a policeman and gave their descriptions. They were arrested a short time later. However at the trial Kean produced a number of good character witnesses who testified to his excellent service with both the CID and Protection Corps and seems to have won over the jury with a case of mistaken identity. He was found not guilty of intimidation. It’s difficult to assess just how much incidents such as this may have affected the family’s quest for recognition of Michael junior but it may well have been hovering in the background of their numerous pension applications on behalf of their brother. This incident certainly suggests that they may have been active on the anti-treaty side and that their home may have been used as a safe-house for activists on the run.

The fight for recognition of Michael O’Doherty’s service took a heavy toll on the family. Joseph, who had never had good health, died on 26th November 1924. Margaret, Michael’s mother, who, according to Lily had never recovered from her son’s death, died on 16th August 1926. The house at No. 10 Mayor Street was sold that year. Michael Senior, finally worn down by all his efforts, died on 19th January 1932. Lilly O’Doherty now took up the fight. In an intervention on her behalf by Labour Senator Thomas Johnson, it was stated that despite whatever the “formal documents” might say, that “there is not the smallest doubt that he died from wounds received as a soldier of the Irish Citizen Army on active service during Easter Week 1916.” Matters were further complicated by the fact that Dr. Dolan who had treated O’Doherty, was now dead. While there was a willingness to understand that this was a special case, under the terms of the act, only a dependent under 21, or who was an invalid, could benefit, and as Lily, the latest member of the family to apply, was neither, her case was again rejected. Theresa O’Doherty, who had suffered from spinal troubles from 10 years of age next applied. According to her Dr. Dolan had only examined Michael once the day before he died and wouldn’t have been in a position to diagnose cancer of any kind from that examination. In her supporting evidence, the Rev. Canon Flood, former Parish Priest of St Lawrence O’Toole’s stated that O’Doherty was so badly wounded, that “his living so long was considered almost a miracle.” The O’Doherty’s would continue to fight for recognition of Michael up to 1961 with the authorities continually claiming that his death had not been caused by wounds received in Easter week or a disease caused by Military Service.

What recognition the family did receive finally came through the National Graves Association in 1936. In November that year the NGA unveiled gravestones to Sean Healy, Dan Murray, and Michael O’Doherty at Glasnevin. In keeping with the times, while the gravestones were unveiled by George Plunkett, the actual speeches or graveyard orations had to be held in nearby DeCourcy Square as it was seen as a political event. The rules of Glasnevin prohibited political speeches at Funerals.

The final fight for the O’Doherty’s came in 1973. At that stage the three remaining sisters had a shop at Summerhill Parade over which they lived. A number of local residents still remember them with great warmth and affection. Shortly after 11.00pm on Sunday 1st January 1973 a number of young men who had been drinking nearby decided to break into the shop to get more drinking money. Alarmed at the noise the sisters decided to defend themselves. It was probably not the wisest course of action but given their background and history it seems unlikely that they could have chosen to act differently. Kathleen, then aged 73 was badly beaten and cut around the eyes and face, while Theresa, then 75, had her leg broken during the assault. Lily, by then an invalid, had to be treated for shock. There was a total of £10 in the till. Lily died on the 1st January 1974.

Our thanks to Con O’Doherty for assistance with Family background and traditions. Jimmy Wren for assistance with the history of the GAA in the North Dock area. The Irish Military Archives, The National Archives, National Library, and Dublin City Archives for material in their care used in this piece.

For clarifications, corrections or further information please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

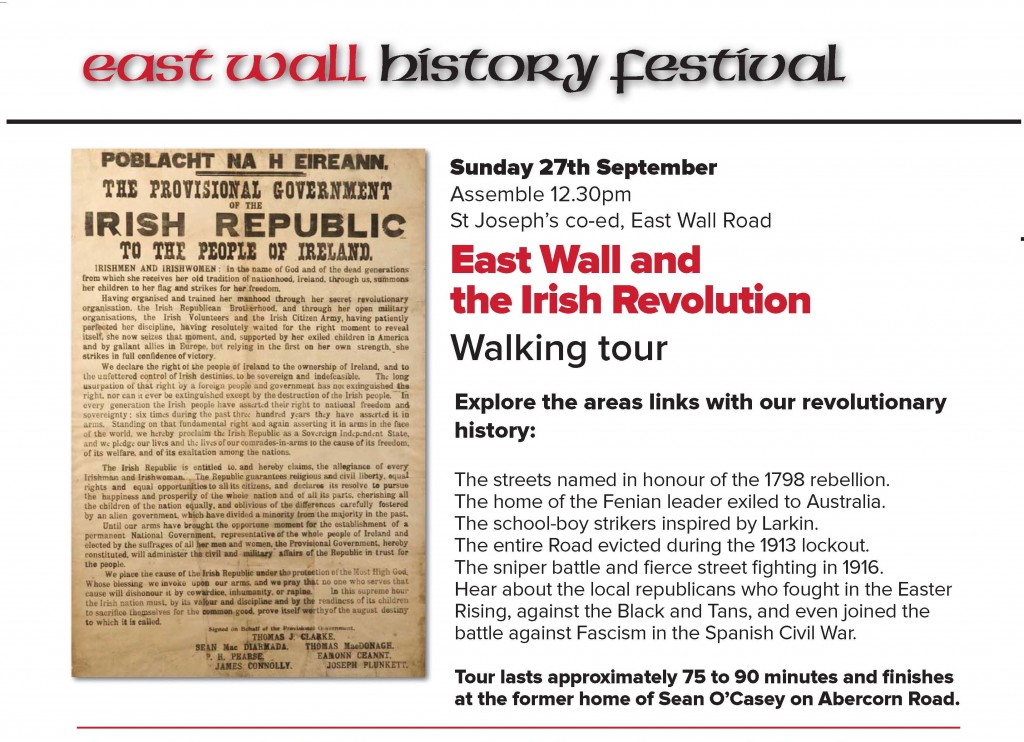

Sep 20

The Reluctant Volunteer: The story of John Dutton Cooper

“…some practical demonstration of the nations gratitude to one who took a risk in its hour of need.”

On Sunday the 23rd October 1938, at a less than full Croke Park, the crowd saw a tightly fought replay between Galway and Kerry in the All Ireland Football Final. With minutes to go and trailing by 5 points, Kerry rallied, but failing to score more than 2 points Galway were crowned champions. Among the crowd were large numbers of 1916 Rising veterans who were introduced to the crowd at half-time to great appreciation. Many had been there from earlier in the day for what would become an iconic photograph of over 350 survivors of the 1916 GPO Garrison. There was some delay while two of their colleagues were brought from the South Dublin Union. In the case of one of these two men it would be the only known photograph to be taken of him. His name was John Dutton Cooper and this is his story.

The Coopers were one of that forgotten tribe of Dublin protestant working class artisans of the late 19th Century whose subsistence depended on the boom and bust of their profession. Samuel Cooper had been apprenticed as an upholsterer just as a golden age of furniture making in Dublin was going into decline. He had been born at 72 New Street on 5th May 1837, the second child born to John and Maria Cooper to bear that name. A previous son named Samuel had been born in 1829 but had died young. Samuel was 32 when he married Harriet Dutton in 1869. He was living in Aungier Street while she lived at 32 Camden Street and it was at Harriet’s parents house that their first son, John Dutton Cooper was born on 10th April 1870. The fortunes of the family can be trace through the births of their children showing the family on the move every 2-3 years. Black Pitts, McGronan’s Cottages, Bloomfield Place, and Bonny’s Lane were some of the stop offs by the Coopers until we find them in the 1901 Census at 20 Long Lane in the Liberties.

Harriet was now working as a nurse while both she and her husband described themselves as Baptists a sign of the late 19th century evangelical revival in Dublin. On the other hand their son, John Dutton, described himself as a Free Thinker, a philosophy developed by the mathematician and philosopher William Kingdon Clifford in his 1870s publication “The Ethics of Belief”. Freethinkers held the viewpoint that positions regarding truth should be formed on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism rather than authority or tradition. They believed in forming their own opinion on religion and other matters through the use of scientific inquiry and logic rather than set beliefs as outlined in texts such as the bible. This may have been a sign of rebellion against his parents and demonstrating his independence however it does show an inquisitive mind and an unwillingness to blindly accept the status quo without examining it first.

By 1911 the family were all describing themselves as Church of Ireland again, and Dutton Cooper was working as a Druggist’s Assistant. (Chemists in those days made up their own medicines). In 1901 he had been studying the “Hygiene Art” but it doesn’t appear to have amounted to anything. As he was later described as a manufacturing chemist it seems likely that he served an apprenticeship at some stage. However it was usual, although not compulsory, to obtain a licence from or at least be registered with the Royal College of Physicians. A search through their records showed no results so it’s likely that he had some experience or apprenticeship but may never have actually sat any exams. Crucially during this period the Coopers had moved to 13 Aldeborough Parade (described at the time as ‘off Seville Place’).

Seville Place was home to many of the successful cattle exporters who did business through Dublin Port. Like the North Strand Road it also contained the dwellings of artisans, craftsmen, and lower grade civil servants. However it quickly gave way to the poorly constructed cottages and tenements of the dockland workers who were the majority of inhabitants in the area. The same demographic was demonstrated in the Cooper’s Parish Church on the North Strand Road, known as the Ivy Church, the Rector of which, the Reverend Lewis Crosby played a very important role during the turbulent years of 1911 – 14. A man of independent means Lewis Crosby was deeply affected by the poverty among many of his parishioners and it was this that gave him common ground with James Larkin, leader of the ITGWU, in a effort to provide relief to the areas poorest. Lewis Crosby even went so far as to hire health workers to visit throughout the area in order to identify and relieve the poverty stricken.

In 1911 a national strike of Railwaymen was organised in England. A sympathetic strike took place in Ireland with the workers of the London and North Western Railway walking out of work at the North Wall on the 18th August. It quickly spread through the staff of the Great Northern Railway at Amiens Street with other railways following. The National Strike was quickly solved but the Irish strike grew with sympathy strikes among the staff of timber merchants and ultimately the strike became about Trade Union recognition. Ultimately the strike was broken with many loosing their jobs and according to ICA man Peter Carpenter created the appetite and legacy among workers for what would become the Great Lockout of 1913. Living in the midst of all this, and dealing directly with it’s effects through his job as a dispensing chemist, affected John Dutton Cooper. He became acquainted with James Connolly at this time and having moved to Lennox Street he joined the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) becoming part of the South Circular Road section either towards the end of 1914 or early 1915.

Dutton Cooper had begun working as a traveling salesman for a company called Inks & Co meaning irregular hours which made a commitment to the ICA difficult. However he seems to have taken a keen interest in Kathleen Lynn’s medical classes probably due to his training as a chemist. The lack of documentation makes it hard to be certain but while Dutton Cooper may have logically calculated the righteousness of the socialist cause, he, like many conscientious objectors, may have been opposed to the actual violence involved in a revolution. Much of the burden of supporting his ageing parents fell on him by this time and the pressures of an on the road salesman meant he had less time to devote to other matters. In the 1915 mobilisation rolls compiled by Thomas Kain his name was crossed out. However on Easter Monday he found himself in the O’Connell Street area and witnessing a civilian being wounded went to his aid. The following day to went to the GPO to offer his services.

Cooper didn’t take up arms, instead hauling coal from the basement, helped to erect barricades, and generally undertook non-military work. Eventually he joined the Red Cross section commanded by Dr. Jim Ryan under which he signed Brother Allen’s GPO Garrison autograph album. However in his pension application statement he says he acted as a stretcher bearer. It was Cooper who brought the stretcher for James Connolly after he was wounded in Princes Street although Cooper was too slight to carry Connolly and so he handed that duty to others. On Friday he was evacuated with the nurses and wounded to Jervis Street. The following day he was arrested and taken to Kilmainham Jail from where he was deported to Wakefield and later Frongoch where he was held until August.

Believed to show James Connolly on stretcher ,after surrender. ( Photo from “The 1916 Diaries of an Irish Rebel and a British Soldier” by Mick O’Farrell)

Throughout his imprisonment Coopers family were assisted by the Irish National Aid Association until his release. He immediately made contact with Kathleen Lynn later rejoining the ICA when it began to regroup in 1917 but he found little in common with the other members and according to John Hanratty had difficulties accepting orders and discipline. By the late 1920s his health was in decline and by 1935 was a resident in the Protestant Hospital of the South Dublin Union. According to ICA man Edward Mannering, Cooper had been offered a pension application form by a visiting clergyman but found the process too complicated so he never applied. Intervening on his behalf the following year, veteran ICA man Frank Robbins wrote “Cooper is a pauper inmate in the Union. Perhaps you could do something for him and thereby give some practical demonstration of the nations gratitude to one who took a risk in its hour of need.” After a four year effort he was awarded a pension of six shillings per week of which five were taken for his keep.

A letter writer to the Irish Independent in April 1939 urged the Fianna Fail government to “give a little more thought and attention to the living and a little less to political exploitation of our dead.” He went on to state that “we have at least three Easter Week heroes as common paupers in the South Dublin Union. Bob Oman (four years confined with a paralytic stroke), Tom Croke (five and a half years in bed with Bright’s disease in the skin and epileptic ward) and John Cooper in the health yard for the past two years. The last named has a pension from the government of 6/= a week of which 5/= is deducted for his keep.” The writer appealed to the government to visit the South Dublin Union to see the miserable conditions of these men and to look outside at the plight of many more “who are postponing from day to day their entry to the same place of condemnation.” Finally he called on the Fianna Fail National Executive “in God’s Holy Name, to do something really genuine for the few that still live, and who have been politically used and abused by the government. And to be a little more charitable to them.”

Dutton Cooper seems to have accepted his fate at the South Dublin Union but some sense of what it was like can be found in the correspondence of both Tom Croke and Bob Oman to the Pensions Board. Croke had been a civil servant from before the Rising and had been reinstated after independence. Succumbing to Bright’s Disease he fell on hard times and ended up in the South Dublin Union. Writing to Oscar Traynor in May 1937 he stated that he was in receipt of a pension of 7 shillings and three pence per week “in acknowledgement of military services rendered with the Irish Volunteers at the GPO of Easter Week, 1916, and my names appears as such on the roll of honor in the Kildare Street museum” adding it could hardly be consistent with such honor to be forced to live the life provided by the Union. His great pleasure was reading but this was impossible due to the “ audacious conduct of those who seek the asylum and safe refuge, from the ranks of the wastrels, near-do-wells and the criminal classes, have got to be personally experiences before belief in the irregularities could be for one moment entertained as possible.” As a 1916 man who had served his country he called on the Minister to find some place where he and colleagues like him could end their days in dignity. As Croke put it in a previous letter to Traynor two years previously, “such an ending as this in which I now find myself placed can hardly be regarded as consistent with the honors lately conferred after 19 years of hope and expectation.”

Of particular annoyance to Croke was the fact that the Union attempted to force him to sign over his pension leading him to refuse signing the drafts at all after they arrived. He felt this was illegal. Having served his country he couldn’t understand that that same country would take back the little pension it provided him with for what he saw as poor treatment by the Union. Bob Oman had similar problems with the Union trying to obtain his pension too. He arranged for the drafts to be sent to his sister then looking after his young motherless children. Oman had developed an infection while in detention in Gormanstown Camp with among others the same Minister of Defense, Oscar Traynor. This was diagnosed as Post Encephalitis or Parkinsonism, a viral infection leading to a degeneration of the nervous system which left him semi-permanently paralyzed, The Board refused to accept it was contracted due to military service. Despite being in incredible pain and under huge pressure to hand over his pension, Oman refused, trying to provide in some small way for his children with the little means available to him. At one stage, unable to write his name, he arranged for a local priest to sign on is behalf. Following objections by Croke and a query by the Pensions Board, the Resident Medical Officer stated “ so many pensioners of every description seek admission here that the matter of their contribution towards their maintenance is one of particular importance to the Board of Assistance.” Croke died in 1942 and Oman in 1955. Surviving evidence suggests that they never handed over their pension money despite the continuous pressure. However Dutton Cooper doesn’t appear to have had much choice.

In 1938 , before the Galway v Kerry All Ireland Final Reply on the 23rd October special arrangements were made for what would be that iconic photograph of the survivors of the GPO Garrison at Croke Park. Special arrangements were made for Dutton Cooper and ICA colleague Paddy Devereux to be brought from the South Dublin Union to the session. Both were late, and neither appear in the published list of those in the picture. However according to journalist Annie Kelly they arrived in time for the photographer. If this is correct it is the only known photograph of John Dutton Cooper. Unfortunately as there appears to be no actual key to who is who in the shot we may never know what Dutton Cooper looked like. After the session those present passed a hat around for their two colleagues being particularly disturbed that Dutton Cooper had to hand up five of his six shillings pension to the Hospital.

John Dutton Cooper died on the 1st July 1943 of a rare form of liver cancer. He was 70 years old. His family, then in poor circumstances, had great difficulty with the financial burden involved with his funeral. The following April in the Dail James Larkin asked Minister for Defence, Oscar Traynor, whether he would consider John Dutton Cooper’s case and repay the funeral expenses involved. He also asked Traynor to associate his name with the National Graves Association. Traynor replied that if he was provided with the details he would consider it. There is no surviving evidence that he did either.

For clarifications, corrections or further information contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Images sourced by Hugo McGuinness.

With gratitude to Jimmy Wren, author of upcoming book on the GPO Garrison, for his ongoing assistance.

Sources include: Bureau of Military History Pension files, ‘Labour News’ and other newspapers of the era.

Sep 14

Together in Arms: Kathleen Lynn and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen

Together in Arms

Kathleen Lynn’s relationship with Madeleine ffrench-Mullen

by Carmel E. Darcy

Why are the names of Dr. Kathleen Lynn and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen inseparably linked?

Using mainly the diaries of Kathleen Lynn, I will examine the thirty-year relationship between Kathleen and Madeleine in this paper. What was the nature of their relationship, and if they were alive today would they be regarded as lesbians? Who were their friends, and did they move in a circle of like-minded women? Was their relationship an open secret among their friends? How did Kathleen get on with men and is there any evidence of a male relationship? What, if anything does Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh, Kathleen Lynn’s biographer and a leading authority on her life, say on the subject. I will endeavour to answer these questions. How their families viewed their relationship will also be looked at, as will the social constraints of such a union in Ireland, in the early part of the twentieth century.

Both women were of the establishment class and were comfortably well off. They lived together in Rathmines Dublin for thirty years and were devoted to each other. In the words of Marie Mulholland – ‘Madeleine and Kathleen were regarded as a team by friends, comrades and colleagues, and if alive today would be called lesbians’. (Marie Mulholland, The politics and relationships of Kathleen Lynn). Roy Foster in his book Vivid faces, describes their thirty-year relationship as ‘having all the marks of a marriage’.

Kathleen was born in 1874 and Madeleine in 1880 but they did not meet until 1913 when Kathleen was 39 years old and Madeleine 33 years old. They began to live together in 1915 and continued to do so until Madeleine’s death in 1944. It is difficult to tell if they had other relationships with males or females before this time, as Kathleen did not begin to write her diary – from which most of the information for this paper has been taken – until 1916. The diaries have been transcribed by Margaret Connolly and are held in the College of Physicians of Ireland in Kildare Street. They span forty years until Kathleen’s death in 1955. Madeleine also wrote a short diary while in prison, covering the period between 5th and 20th May 1916.

In the diaries we find evidence of a gentle and loving relationship between the two women. In Kathleen’s diary Madeleine is generally referred to as ‘dearest MffM’. In her evidence to the Bureau of Military history in March 1950, Kathleen describes Madeleine as her ‘closest friend’. Madeleine was in hospital having a goitre removed in December 1916 and Kathleen anticipates her discharge by writing ‘Madeleine, coming home to me tomorrow’.

Rosamund Jacob was a friend to both women and she records in her diary that neither Kathleen or Madeleine ‘had any use at all for men’. She records going to their house in Rathmines and speaking to both while ‘they breakfasted in bed, as was their custom’, (Rosamund Jacob diary, 21 September 1920). Like any couple they enjoyed celebrating special events and Kathleen recorded that they were ‘out ‘til dawn’ on the night in 1920 when both were elected to Rathmines and Rathgar Urban District Council. They also fretted over one another in times of sickness, loss or trouble and particularly during times of curfew when one or other would be away from home late at night.

Although Madeleine’s mother was a frequent visitor to their home in Rathmines, there is no evidence that Madeleine ever accompanied Kathleen on visits to Cong in Mayo when Kathleen visited her father and sisters. Kathleen had a fraught relationship with her family mainly due to her republican leanings but perhaps also due to her relationship with Madeleine.

Kathleen worried over Madeleines health and often mentions in the diaries how hard Madeleine worked in St Ultan’s Hospital, saying that she was ‘killed with work’. Kathleen’s health was more robust than Madeleine’s but she was still prone to colds and ‘flu and on one occasion writes how she promised Madeleine that she would ‘stay in bed all day’, which would have been a very rare thing for Kathleen to do. Throughout her diary Kathleen often mention small gifts being given to her by Madeleine, mostly plants and flowers.

Of necessity Kathleen was often away from home but always reported how nice it was to return and how happy Madeleine always was to see her. In summer of 1919 Madeleine went on holiday with her mother and Kathleen recorded on her return – ‘great to see Madeleine again, she looks well’. Small personal events such as Madeleine getting a new coat are also recorded and Kathleen remarked how well she looked wearing it.

In June 1922 Kathleen was in Waterford with the Republicans and thinking of home ‘longed to know how they all were’. In December of that year Kathleen was in Manchester and reported that she was ‘sorry to leave M again so soon’.

The group of women in which Kathleen and Madeleine moved were educated, independent and spirited and perhaps did not match the picture of the ideal woman of the time who stayed at home and took on the views and politics of her husband. Women at the beginning of the twentieth-century were valued as wives and mothers. However, Kathleen and Madeleine and their friends were involved in the Suffrage Movement, and the Cultural Revival. Some of these friends were also in female partnerships, such as Louie Bennett and Helen Chenevix, Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper and Elizabeth O’Farrell and Julia Grenan.

The women of 1916 , with Mullen (left) and Lynn (right) in the front row (Image courtesy :Kilmainhamtales.ie)

After the week of rebellion at Easter 1916 both women shared a cell in Kilmainhan Jail and Madeleine described in her diary how ‘the doctor and I settled down to life and agreed that as long as we are left together, prison was somewhat bearable’. Both women were then moved to Mountjoy Prison and were incarcerated in separate cells and Kathleen being very lonely reported in her diary that she ‘would give ten thousand pounds for Kilmainhan and Madeleine’.

They were both lovers of the outdoors and spent as much time as they could in their retreat in Glenmalure, county Wicklow, where they enjoyed ‘getting up very late and bathing in the river and then getting back into bed to warm up’. Unfortunately Madeleine died in 1944 at the age of sixty four and on the first anniversary of her death, Kathleen reminisced on how ‘Madeleine would nestle down close to me, while I sat beside her, with her head on my shoulder’. Kathleen was very lonely after Madeleine’s death and described coming home to the empty house – ‘the loneliness of coming back with no MffM to greet me and say what a barren wilderness it had been while I was away’.

Was their exclusion from main-stream history because of their relationship or was it simply because they were women? Perhaps the reasons are two-fold. Marie Mulholland contends that Kathleen’s life choices led to her estrangement from her family. Mulholland says that Kathleen’s diaries contain ‘frank and loving references to Madeleine that are at odds with her often dispassionate accounts of revolutionary and other events’. She asserts that the women loved one another deeply and passionately. From reading Kathleen’s diaries I have not found much passion in the accepted sense but plenty of caring and loving. Kathleen Lynn was always extremely circumspect in her conduct and in her writings. Love and fellowship were at the heart of her life, with Madeleine at its centre.

Kathleen Lynn’s biographer, the late Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh described the women as being life-long companions, dearest friends, and confidantes but does not enlarge on any sexual relationship. What can be said with certainty is that they were for thirty years inexorably bound to one another in a warm and caring relationship.

Based on the paper delivered by Carmel Darcy at the inaugural Sarah Lundberg Summer School: “Kathleen Lynn, A truly Radical Woman”, held on the 18th July 2015 at the Sean O’Casey Theatre, East Wall. (Used with permission)

For any comments , clarifications or corrections please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Sep 14

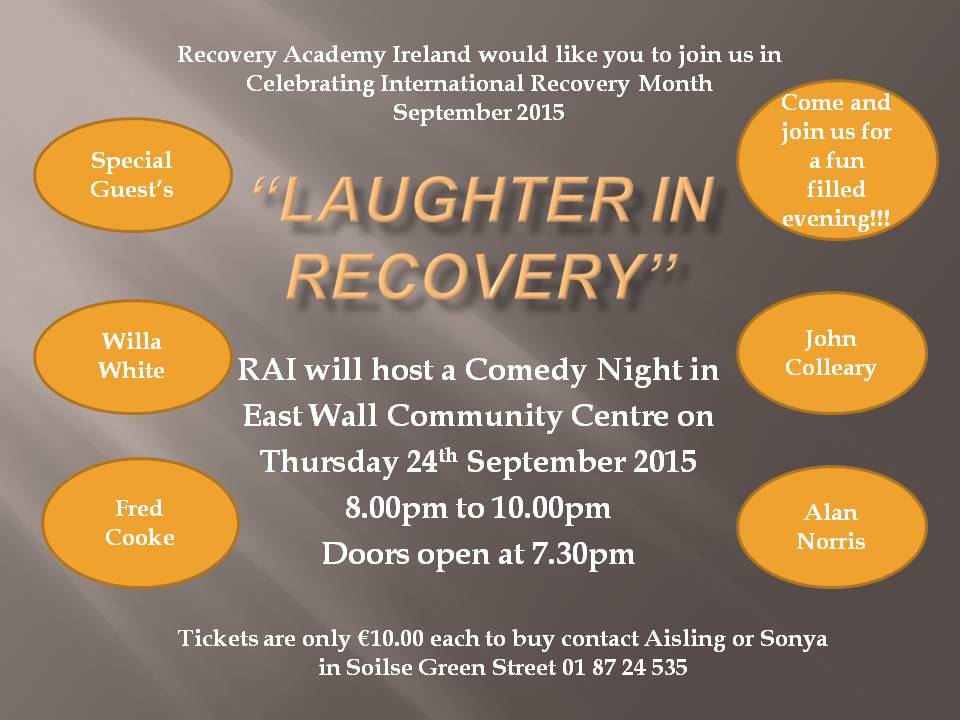

“LAUGHTER IN RECOVERY” – at the Sean O’Casey Theatre

Celebrating Recovery from Drug Addiction

A conference, comedy night and awards presentation are among the highlights of International Recovery Month 2015 organised by Soilse, the HSE drug rehabilitation programme based in Dublin’s north inner city.

Celebrated around the world each September, International Recovery Month shows that people with drug addiction problems can and do recover from chronic substance abuse and go on to build healthy lives. It challenges the stigma a around drug addiction and gives hope to drug users, their families and communities struggling with addiction.

Soilse works closely with recovering drug users and has been to the forefront in efforts to promote recovery and sustainable drug-free lifestyles.

Sep 06

Kathleen Lynn: the rebel doctor and the North Docks – A history and appreciation

“A very busy evening…not home until very late.”

On Thursday evening, the 8th June 1916, word spread among dockside workers that a very special republican prisoner was about to be deported. As the prisoner arrived on the quays a great cheer went up from the gathering crowd. The prisoner in question was Doctor Kathleen Lynn, chief medical officer of the Irish Citizen Army who had fought at the City Hall in the recent rebellion. For many of those cheering she was the kindly lady who had treated them and their children at Liberty Hall in 1913 during the dark days of the lockout. And afterwards, in August of 1915 she began instructing the ICA women’s sections Ambulance Corps. And it was not just the ‘transport union’ types that valued Lynn and her work. A correspondent , describing themselves as “A Loyalist and Unionist” writing of Lynn’s deportation in the Freemans Journal claimed that for many years she ran free clinics at The Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital and that Dublin “owes Dr. Lynn a great debt of gratitude.“ He went on to say that “as an honourable Christian lady … the present generation has seen few equals of Doctor Lynn, and no superiors.” It was known that Lynn never asked whether you had the money for treatment, only what the symptoms were. In fact it was said she never took a payment from the poor, so much so, that in 1917 Countess Markievicz remarked that “her paying patients must almost all be in the enemy camp!”

Maire Comerford of Cumann na mBan and a lifelong republican, remembered her as the embodiment of the line in the proclamation to “cherish all the children of the Nation equally.” She claimed that Lynn held that “every child was an individual and must know himself, or herself, loved.” Bill Oman of the ICA, many of whose 11 children were treated by Lynn said “to know her was to love her, and one had only to see her attend a sick baby to realise her great love of her profession.” Those who were treated by her remember her powerful diagnostic skills as she probed you with careful questions to discover your ailments. Phil Churchill, treated for TB by Kathleen Lynn, remembers it as if she stared right into your soul. With children, each answer would be responded to with calm all knowing “quite! quite!” Then as if to reassure you, Lynn would summon a second opinion by carefully taking your hand, and reading your lifeline, would confidently reassure you that everything was going to be fine.

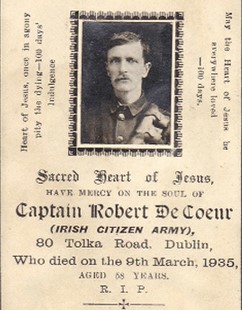

Lynn was a strong believer in the healing powers of good clean air. She commissioned the architect Michael Scott to build a balcony at her home on Belgrave Road, and throughout her life, on fine evenings, would sleep on the Balcony. When she discovered that former Sheriff Street and North Strand resident Bob DeCoeur, an officer in the Citizen Army, was suffering from Tuberculosis, she arranged for him to spend some time with her friend, Dr. Eleanor Fleury, at Manor Kilbride in Wicklow, which almost certainly prolonging his life by several years.

During the 1936 debates on clearing the inner city slums in Dublin Lynn argued that Flats should have “wide balconies where the perambulator can be put out, and the toddler take the air under his mother’s eye.” She further argued that the complexes should not take up the whole space, calling for communal playgrounds and gardens where “little ones could play in safety.” Many of these ideas were to be incorporated in the Charlemont Street development designed by Michael Scott for the Charlemont Public Utility Society in the 1940s although only one block, fFrench-Mullen House was built. (This was a project inspired to some degree by the initiatives of Canon DH Hall of St Barnabas Parish, who was responsible for significant progress in house building in the North Docks).

It was probably Lynn’s influence and championing of ‘fresh air’ which saw the Old Citizen Army Associations charity work include days out in the countryside for young inner city children. She had even extended this passion at one time to the treatment of TB patients at St. Ultans by placing sufferers of the disease on the hospital roof.

It was the same love of the outdoors that saw her leave the cottage at Glenmalure (given to her by Maude Gonne McBride) to An Oige in her will in 1955. It was later extended to accommodate 20 people in three dormitories, with a common room, kitchen, and modern lighting and heating. The children of ICA veterans Christy and Dina Crothers- Phil Churchill and Eilish Lynch recall visiting Lynn at Glenmalure as children.

Lynn’s Mayo background is believed to have introduced her to the healing powers of herbs and although a brilliant medical student she never lost her interest in the medicinal nature of plants. Interestingly, Bridget Dirrane, one of the first nurses employed at Saint Ultan’s in 1919 was an accomplished herbalist from the Arran Islands having learned that skill from her mother. A generation of children from Rathmines and beyond would remember with horror and embarrassment school lunchtimes consisting of parsley sandwiches while their classmates tucked into more substantial fare. For others it was the exotic healing powers of garlic and milk which was prescribed. The Crothers children still remember with horror Saturday morning excursions to Baggot Street and the only Italian shop in Dublin where this rare and disgusting tasting herb was to be found. However, in compensation, their Father also brought them to the little shop at Liberty Hall where Rosie Hackett could be relied on to provide free bars of chocolate as an antidote. Their mother, Dina Hunter from Irvine Terrace, had trained under Lynn in the ICA at Liberty Hall and also served alongside her at ‘The battle of Dublin’ in 1922. Their father Christy Crothers would lead the honour guard of ICA veterans at Lynn’s funeral in 1956.

It was the same Rosie Hackett who remembered a “midnight mobilisation” of the members of the Irish Citizen Army in late 1918 for a special operation in Charlemont Street. Rosie got the call about 10.30pm and over the next hour and a half all who were called on came without hesitation because, according to Hackett, to obey Lynn’s command was “not a burden but a privilege.” Some months previously as the Flu Pandemic raged throughout Dublin, Lynn, released from her second deportation following the intercession of Dublin’s Lord Mayor, and armed with a large consignment of vaccine, had organised to inoculate the same Citizen Army members at Liberty Hall undoubtedly saving many of their lives. Rosie Hackett and Brigid Davis organised the kitchen, Stephen Murphy organised the men, and together they proceeded to put what would became Saint Ultan’s Children’s Hospital in order. The building work necessary to adapt the premises was carried out by one time “back of the church” resident James O’Neill and his Irish Citizen Army building crew in between the refurbishment of Liberty Hall. Ironically their first patient was Citizen Army man Bill Oman who collapsed with the flu shortly after his wedding. His progress to recovery is chronicled in the pages of Lynn’s diaries.

One of the early recruits to work at Saint Ultan’s was Fly Caffrey from Abercorn Road. Fly had literally been born on the dockside, as his mother gave birth on a ship while being transported to England. Normally, under such circumstances, someone would have simply wrung Fly’s neck. Thankfully, Mick Caffrey took a shine to the infant, he was spared this grisly fate and Mick took him home and reared him. Fly was a lamb, who promptly grew up believing he was a dog and behaving accordingly. To the delight of local children he took them for rides on his back and joined in their childhood games on the street whether invited to or not. Local children would knock on the Caffery’s door to ask if Fly could come out to play and often returned minutes later crying “Mrs Caffrey Fly chased me and knocked me down.” Fly obviously had a winning personality because Lynn also took a shine to him, and he eventually took up residence and employment at St Ultans.It was a wrench to the family and a great loss to a generation of Abercorn Road children but for a number of years the grass of Saint Ultan’s Garden was kept in peak condition by this one time popular North Dock resident. Christine Caffrey had served under Lynn in the Citizens Army and was a veteran of the Stephens Green Garrison in 1916. To the Caffrey’s, presenting Fly repaid a debt long overdue.

Back row, from right to left is Christine Caffrey, Brigid Davis, Maire Ryan and Rosie Hackett (partly obscured).

Fly wasn’t the only animal to make an appearance at Saint Ultan’s. The annual reports on the state of public health in Dublin list fines imposed by Sir Charles Cameron on unscrupulous Dairy owners who purveyed what Lynn called “poison” on an unsuspecting public. There had been over 1100 of them in Dublin in 1886 and over the next forty years Cameron’s campaigning saw them reduced to 224 by 1914. Diluting milk with water and increasing the salt content were part of unsanitary production practices. This essential beverage often carried tuberculosis and typhoid contributing greatly to the infant mortality rate in the city. Lynn’s plan to circumvent this was to acquire a small herd of goats for St Ultan’s guaranteeing a constant supply of pure nutritional milk for the infants in their care. Fly Caffrey kept his new companions in check. Following his sad death they regularly wrecked havoc in the hospitals grounds as the gardener struggled to exert control of this most useful but unruly crew.

During the Rising, Michael O’Doherty from Common Street was shot 14 times at Stephens Green. He was a prominent Trade Unionist with the ITGWU and had a degree of vanity about his appearance. In a 1913 photograph of Larkin speaking in O’Connell Street he can be seen with his hat tilted upwards to the left with a similar pose seen in the ICA photo outside Liberty Hall with the “Neither King nor Kaiser Banner” unfurled. O’Doherty was taken to Mercers Hospital and later the military hospital at Dublin Castle. A VAD nurse there was so concerned for the extent of his wounds as she watched the blood seep through the bandages covering his head that she daily prayed that he would die. However he made a full recovery although his face was horribly disfigured, but vain as ever, he simply looked for assistance to comb his hair and proceeded to inspire all the patients both rebels and soldiers undergoing treatment. These included Cathal Brugha in the bed beside him who had been shot over 20 times. O’Doherty lost an eye, an ear, and his face was badly distorted from where his cheekbone had been shattered. While the various doctors “did their bit” to patch him up, it was Kathleen Lynn, aware of O’Doherty’s vanity, who arranged to have a false eye fitted at her own expense. O’Doherty died in 1919 and had a spectacular funeral from Laurence O’Toole’s Church organised by Countess Markievicz. Despite his ailments he had some semblance of normality in his final years due to Lynn’s kindness.

During the battle of O’Connell Street in 1922, Maire Comerford recalled Lynn being everywhere, syringe in hand, treating the wounded. When Cathal Brugha’s luck ran out it was Lynn who tried in vain to save his life. Brugha asked that a mass be said for him which she agreed to. It was later asked of a priest on the missions in China to say the annual mass for many years. In gratitude, generations of Chinese boys were christened Cathal Brugha in memory of the Irish Republican.

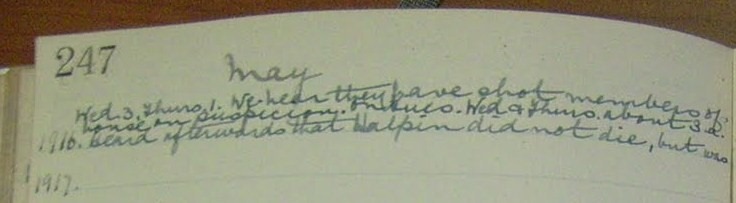

Lynn’s diary, a very under used source for the revolutionary period, begins just before the occupation of City Hall in 1916. It records her capture and imprisonment in Ship Street Barracks where she immediately set out to improve the conditions of her fellow female prisoners. Then over a number of pages she records the progress of Willie Halpin of Hawthorn Terrace including the rumour that he had died in the Castle Hospital on the 27th April. Halpin was Shop Stewart of the United Society of Boilermakers and Shipbuilders at the Dublin Dockyard and Treasurer of the Citizen Army. Willie had hidden in the chimney of the City Hall to evade capture and was close to death when he was discovered. Lynn immediately intervened with the British Army Medical Officer on his behalf which probably saved him.

However, Joe Good, a London born member of the Irish Volunteers, also gives credit to a British soldier for his contribution to Willie’s return from the grave in an amusing anecdote. Willie, although a private in the ICA, had a fondness for wearing a sword and elaborates braid on his uniform. Cruelly his ICA comrades christened him “Napoleon Halpin.“ For Easter week he had invested in so much gold braid that Good described him “as like a chocolate soldier.” Halpin didn’t drink alcohol but a kindly British soldier poured some whiskey into his mouth to revive him, which, according to Good was “the first drop in his abstemious life” and “all but killed him.” The soldiers then carried Willie, “half choking on whiskey, with his scabbard dangling” into a room where several of the condemned leaders of the Rebellion were being held. Then dropping him on the floor, an officious sergeant announced to the assembled leaders “here’s your brigadier general!”

Lynn’s diaries give us a fascinating insight into life during the revolution of 1916 to 1922. In between meetings with most of the major names of the period, she records her medical and political activities, social events, and the development of Saint Ultan’s Children’s Hospital, among other activities which leave you breathless just from reading about them. Of particular interest to North Dock residents is a brief, understated, entry, for the 23rd March 1919 when she records a “very busy evening in Newfoundland Street. Not home until very late. ” We will probably never know the full extent of what that statement represents but in it’s understated way tells us much about Lynn and her relationship with the residents of the North Dock.

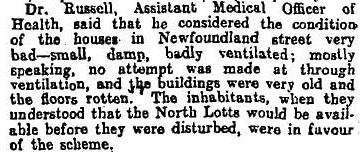

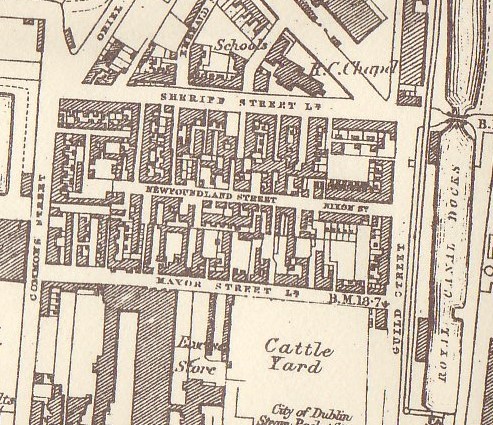

Lynn would have been aware of the living conditions of Newfoundland street and it’s surrounds ,through residents such as John Moore, a 1916 Citizen Army veteran who at that time was smuggling arms and explosives into Liberty Hall on board the Scotch boats of Burns and Laird on which he was a crew member. The street and it’s attrition on the children residing there would be a constant theme of her medical career. Named after its reclaimed origin as part of the North Lotts, literally New-Found-Land ,its proximity to both the river Liffey and Spencer Docks meant that dampness was a constant issue. Hastily built to meet the growing housing needs of dockside workers, its side streets and groups of long forgotten cottages, often too small to register on contemporary maps, were often built by enterprising local publicans and shopkeepers with little capital. Others were built by speculators and regularly sold from the mid nineteenth century as investment blocks with a guaranteed income in some cases listing the residents who came as part of the package in the advertisements. All lacked proper sanitation and in some cases even basic rendering. Cholera, Typhoid, and Tuberculosis were no strangers here.

In 1919 the Supervisor of the Dublin Corporation Sanitary Department stated that Newfoundland Street and its adjacent side streets comprised 375 occupied houses with 1172 rooms, occupied by 516 families or 2215 individuals. 134 of these families lived in one room. The 1911 Census records that over 200 children from families living in these streets had failed to reach maturity. Alice Caulfield, who grew up in Newfoundland Street in the 1920s would recall how her parents died in their 40s and then her four sisters all systematically died of TB. Caulfield herself succumbed to Diphtheria but survived. Rents here were cheap, from 2 shillings to 6/6 for a room or half a cottage and for most of the residents it was essential to remain close to their uncertain casual employment on the docks. The 1925 Civic Survey showed that 80% of North Dock residents lived within a mile of their employment as few could afford the luxury of a tram fare. 1200 inspections of these properties in the North Dock took place between 1918 and 1919 showing that over 50% were beyond repair. During an attempt to obtain an agreement for a loan of £138,312 through the Local Government Board to renovate the Newfoundland Street district in June 1919 William Larkin, President of the Dublin Tenants Association was assaulted and wrestled from the room by W.T. Cosgrave whom he had accused of attempting to “hedge” the Newfoundland Street project. It would be the 1940s before the problem was tackled in any meaningful way. (It was on the site of Newfoundland Street that the Sheriff street flats were built , and is now a large component of the Irish Financial Services Centre , IFSC).

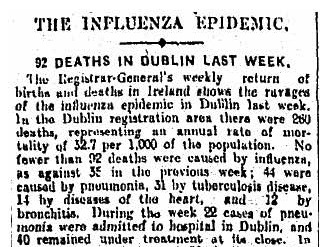

The diet, even of the main earner in a Newfoundland Street family, was poor, usually comprising bacon or a sheep or pigs head, boiled into a type of soup or coddle with whatever vegetables could be got. A 1916 pamphlet produced by the Irish Women’s National Health Association claimed that this type of diet produced 2600 units of energy at least 400 units short of what a manual worker on the Docks required. Alice Caulfield recalled eating roast beef for the first time and being convinced that it must have been bad as it had such a different colour and texture to what she was used to. For children their daily food intake had such a lack of nutrition, that it gave them little to fight the numerous infections which prevailed in the area. Commenting in 1936 on the reduction in Saint Ultan’s death rate among its child patients, Kathleen Lynn specifically mentioned Newfoundland Street as one of the black spots in the city, and stated that its children were sadly among their regular clientele despite so many improvements among other slum areas of Dublin. The Hospital accepted all children whatever their chances of survival. This was the background to Lynn’s “busy night” on the street in March 1919 as the flu Pandemic which killed over 20,000 people in Ireland was going into it’s third phase.(Amongst the many victims in the North Docks was Bella Beaver , nee Casey , the sister of playwright Sean O’Casey).

We will never be able to fully estimate how many lives were saved that night. Lynn, accompanied by her faithful assistant, Brigid Davis, with their flu vaccine in hand, must have had their work cut out. Davis was born in Portrane to a farming family who moved to the markets district of Dublin to become distributors. Here she met Rosie Hackett who introduced her to Liberty Hall and would remain a life long friend. Lynn quickly identified her as a talented and gifted nurse and she was her most trusted assistant until she married Paddy Duffy, whose family still runs the bookbinding business in Seville Place. Few Doctors would enter the area, but Lynn had a simple solution to the unsanitary conditions. She carried a small flask of brandy and both her and Davis would gargle the spirit both before and after entering the infested dwellings. Davis was a lifelong teetotaller but like Lynn, understood that it was a cheap and effective anaesthetic. It saved their lives so that they could save others.

As stated we will never know how many these incredibly brave women saved that “busy night.” The Dublin Corporation Sanitation Report gives us some idea. Because of their bravery many survived and their children and grandchildren are alive today. Many Dublin citizens owe them a debt of gratitude, perhaps even some of those in attendance here today.

(Based on the paper delivered by the East Wall History Group at the inaugural Sarah Lundberg Summer School: “Kathleen Lynn, A truly Radical Woman”, held on the18th July 2015 at the Sean O’Casey Theatre, East Wall).

Contains material shared in oral history interviews with the family of Christy and Dina Crothers, and with Grainne Keely, daughter of Christine Caffrey.

Photo of Brigid Duffy (nee Davis) courtesy of the Duffy family.

Irish Citizen Army photos courtesy Hugo McGuinness

Photo and report of funeral appeared in the Evening Press 16 September 1955 , sourced from the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland archive.

For any comments , clarifications or corrections please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Sep 05