Sep 30

THE FUNERAL OF THOMAS ASHE 1917 : SEAN O’CASEY AND JOHN WHELAN

“Nothing additional remains to be said. That volley which we have just heard is the only speech which it is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian”

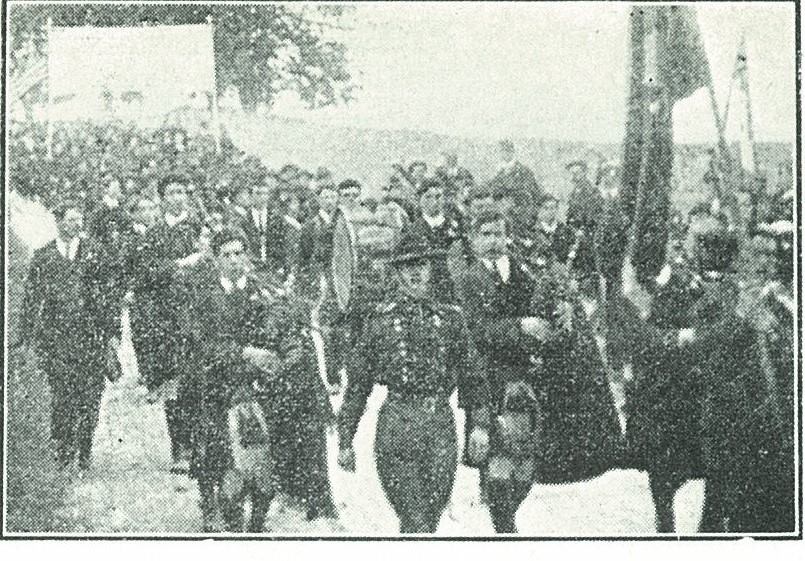

That was the entire oration delivered by Michael Collins at the graveside of Thomas Ashe on this date, 30th September 1917. Thomas Ashe was a member of the Irish Volunteers and in Easter Week led one of the most successful engagements of the Rising at Ashbourne . He was sentenced to death for his role but this was commuted to life imprisonment and he was released as part of the general amnesty. Two months after his release he was arrested for making a seditious speech and sentenced to two years jail. When the prison authorities refused to grant political prisoner status Ashe and other republicans began a hunger strike. A brutal regime of force feeding was introduced, which led to his death in September. His funeral was a momentous occasion for the Republican movement – his body lay in state at City Hall before making it’s way to Glasnevin Cemetery, followed by 30,000 mourners. Members of the Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army took part side by side, and after a volley was fired over the grave side, Michael Collins delivered the short-sharp oration quoted above. Not as lengthy or as eloquent as that delivered by Padraig Pearse at the Graveside of O’Donovan Rossa two years earlier, but in many ways as powerful and fitting for it’s moment in Irish Revolutionary history.

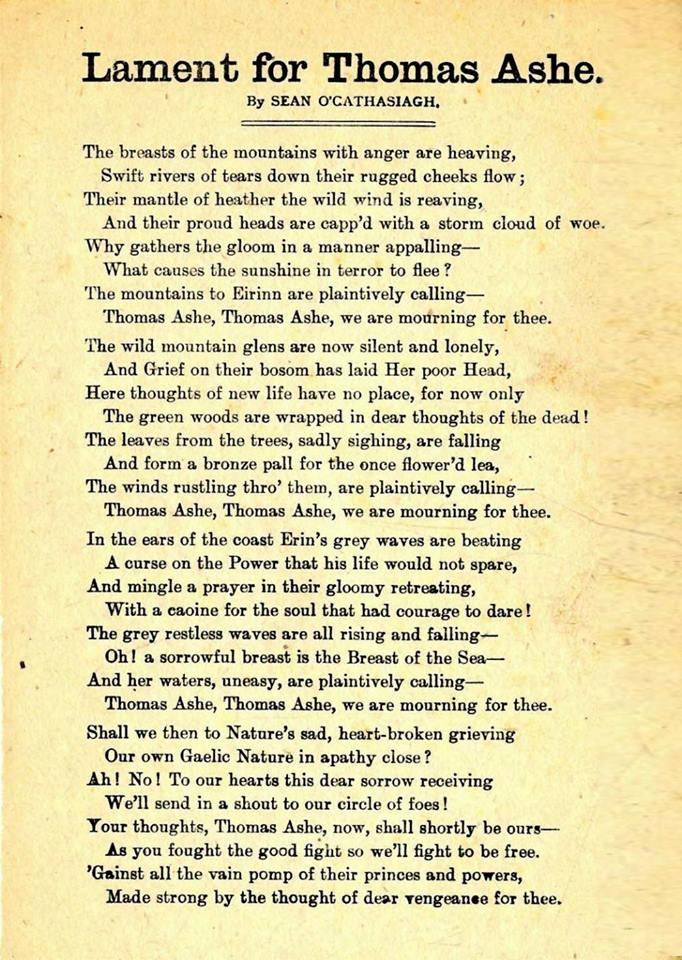

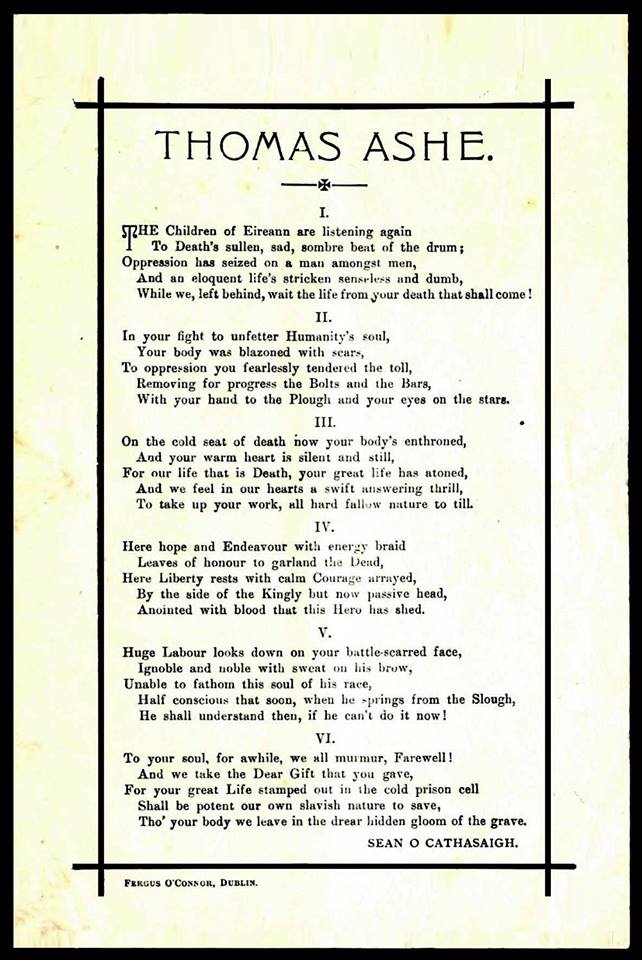

Amongst those greatly affected by the death of Thomas Ashe was Sean O’Casey, who knew Ashe for a number of years . Both had an involvement in pipe bands – O’Casey with the St Laurence O’Tooles (based in Seville Place) and Ashe with the Black Raven band (based in Lusk). In 1913 their respective bands had competed in an all Ireland Championship held in Galway. Apparently they often met and walked along the Quays and discuss politics, and according to Ashe’s sister: “They were united in feeling for the wrongs of the Dublin tenement dwellers”. After his death O’Casey wrote ‘Lament for Thomas Ashe’, published before the funeral took place and possibly distributed outside Mountjoy Jail. He also wrote a short pamphlet which appeared in October, and expanded and reprinted the following year as ‘The sacrifice of Thomas Ashe.’

While the tone of O’Casey’s tributes to Ashe may seem at odds with his later assesment of other Republican figures and the nationalist movement of the time, this matter is somewhat clarified by a letter he sent to the Dublin Saturday Post –

“Labour has reason to mourn the loss of Thomas Ashe: he was ever the workers’ friend and would have always been their champion … it would be well if every Sinn Feiner followed in his steps”.

Amongst the firing party at the funeral was Irish Citizen Army member John Whelan (believed to be fourth from left in photo). In 1935 Whelan moved to number 64 Seaview Avenue, where he lived until his death in 1960.

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

(Images of Poems as originally printed courtesy Aidan Arnold)

Sep 29

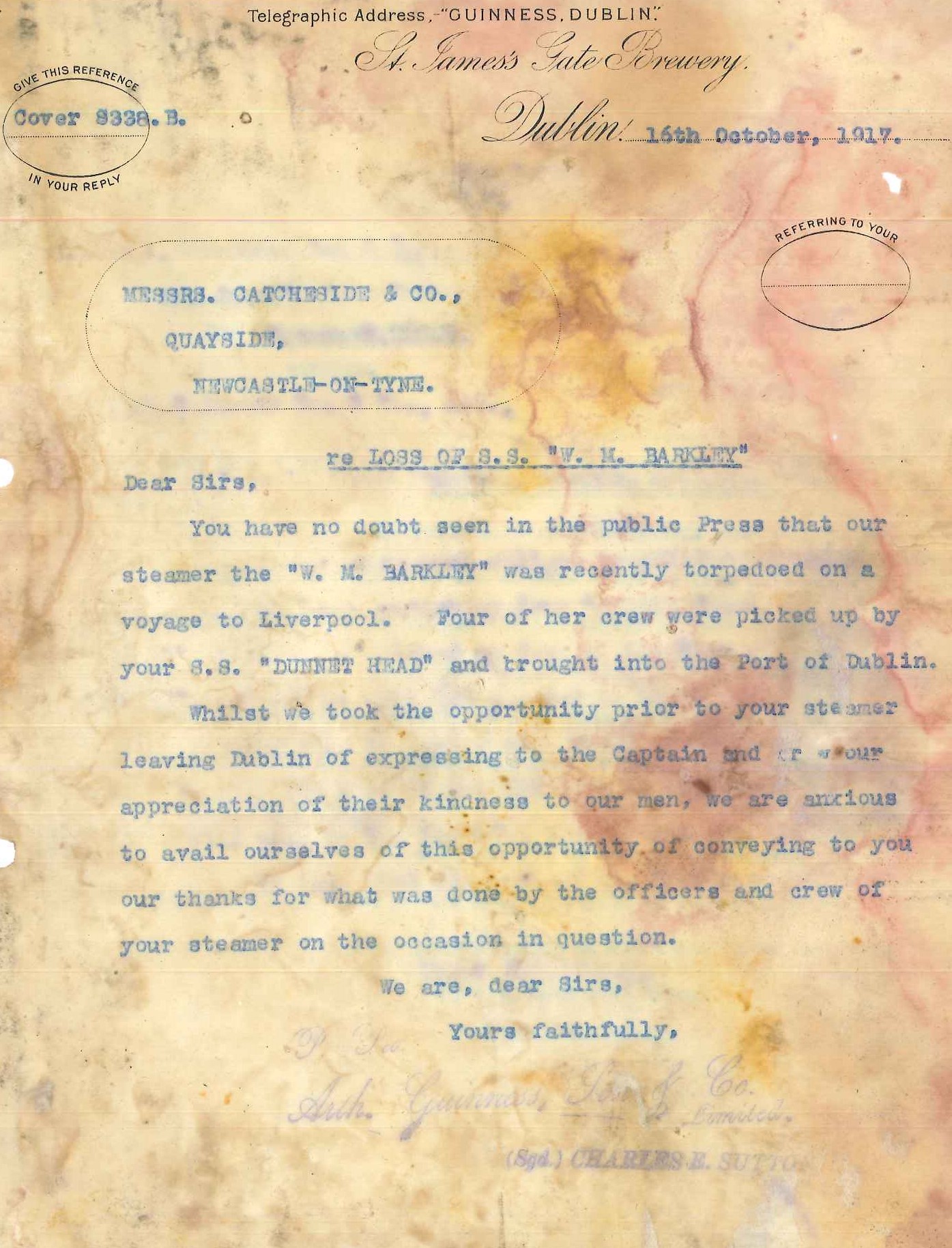

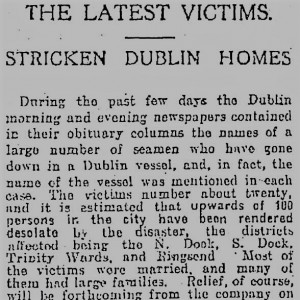

Christopher Wolfe – A North Dock victim of World War One U-boat attack

“Ah I’m going Liz, the lads will think I’ve swallowed the anchor”

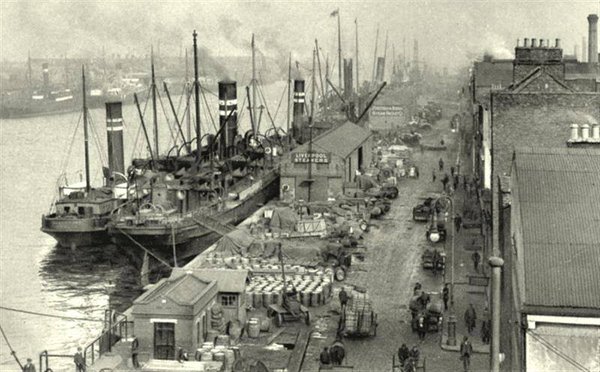

These words were spoken by Christopher Wolfe to his wife on the 27th December 1917 . He left his home at Jane Place (off Seville Place) and that evening set sail on the SS Adela , a Tedcastle & McCormick steamer that had sailed the route between Dublin Port and Liverpool for almost four decades. This was to be it’s final voyage , as just hours later it was struck by a single torpedo , fired by German U-boat U-100 . The SS Adela and her crew were to be the latest victims of the German policy of ‘Unrestricted submarine war’ , the targeting of Merchant vessels in the coastal waters of Ireland and Britain. Twenty four lives were lost in this terrible attack , with only the Captain , Michael Tyrrell surviving. Shay Wolfe , the grandson of Christopher tells his family’s story.

Christopher Wolfe

(1885 -1917)

My Grandfather Christopher Wolfe was born in 1885 and was raised in Leland Place, Common Street in the North Wall area of Dublin. His mother was Margaret Byrne (born either 1855 or 1858) and his father was also Christopher Wolfe (born 1846 or 1847). He had 5 sisters and one brother (Maggie, Teresa, Bridget, Agnes, Lizzie and Lawrence). According to the 1901 census he worked as a quay labourer in Dublin. However, in June of that year he signed on board his first ship, as a ‘boy’ on the Duke of Leinster. This was a Dublin & Manchester Steamship Company passenger ship ,who also operated the SS Hare on the same route .Christopher would actually move to Manchester where he married Elizabeth Tully on 16th June 1910. They had only one child, my father, Christopher Wolfe. They then moved back to Jane Place, off Seville Place (behind Amiens Street train station), and he started working for Tedcastles. He was a winchman on the SS Adela.

When he was killed in the sinking of the SS Adela he left behind his wife Elizabeth and their son Christopher, who was only 6 when his father died. Like so many others they lived in poverty. His wife went on to remarry twice (Mr. Rowan and Tommy Byrne) but didn’t have any more children. She brought up her only son who grew up and marriedBridget Wolfe (Murphy). He and Bridget had 6 children (myself, Christy, Paddy, Don, Larry and Elizabeth). He now has lots of Grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

My own dad worked for a few different shipping companies and did 14 Atlantic convoys. At the end of one of these he was looking for a berth back to Dublin from Liverpool where they had landed. He approached a Captain who, after looking at his papers, realised that he had known his Father. In a twist of fate that Captain was Captain Tyrrell, the only survivor of the sunken SS Adela. He told Christopher that his father was down below in the ship and wouldn’t have stood a chance when the torpedo came in. As a winchman he would have only been back on deck unloading the cargo when the ship docked.

My Grandmother Elizabeth lived with us in 80 East Road, East Wall and we would often hear her sobbing at night. She had had a very hard life and we don’t think she ever got over the loss of her first husband Christopher. She told us that she didn’t want him to sail that day due to the large number of deaths at sea, but he pinched her bum and said “Ah I’m going Liz, the lads will think I’ve swallowed the anchor” (this mean to retire from sea-life and settle down on shore). We also found out that the censor restricted reporting ship losses to stop propaganda for the Germans. She said there were always women crying on the docks and she always made us pray for sailors on stormy nights. We also heard rumours that the SS Adela had carried arms for the rebels in Dublin.

My Grandmother helped rear her and Christopher’s grandchildren and lived a long life with them.

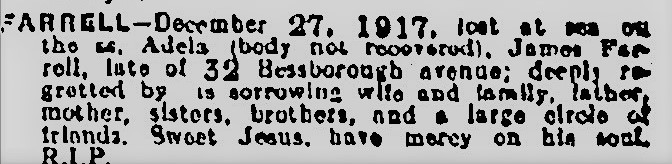

In another twist of fate, the son of one of the other victims on the SS Adela (cattleman James Farrell) married my mother’s sister Nancy Murphy. So there is a real family link to this ship.

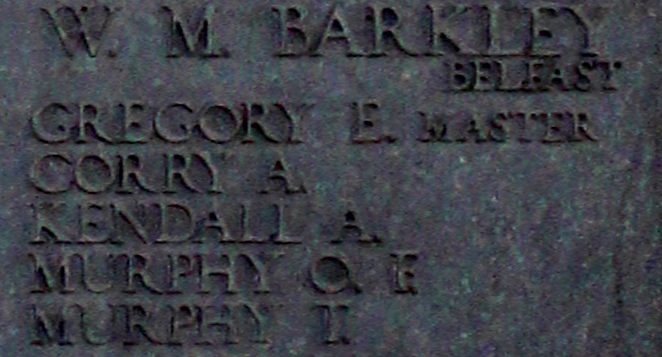

My Grandfather’s legacy lives on in all his grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great-great grandchildren and great-great-great grandchildren. His death gave me a love of history and the docklands and I have spent a lot of time researching his ship. Myself and my wife, Teresa, visited the Tower Hill Memorial in London to see his remembrance on the plaque erected by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

The memorial to him and all who died on the SS Adela and SS Hare that is taking place is a wonderful tribute to those who lost their lives, and, a century on, many of his descendants will attend this memorial to remember him.

(Shay Wolfe)

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” , published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information , corrections or clarifications contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

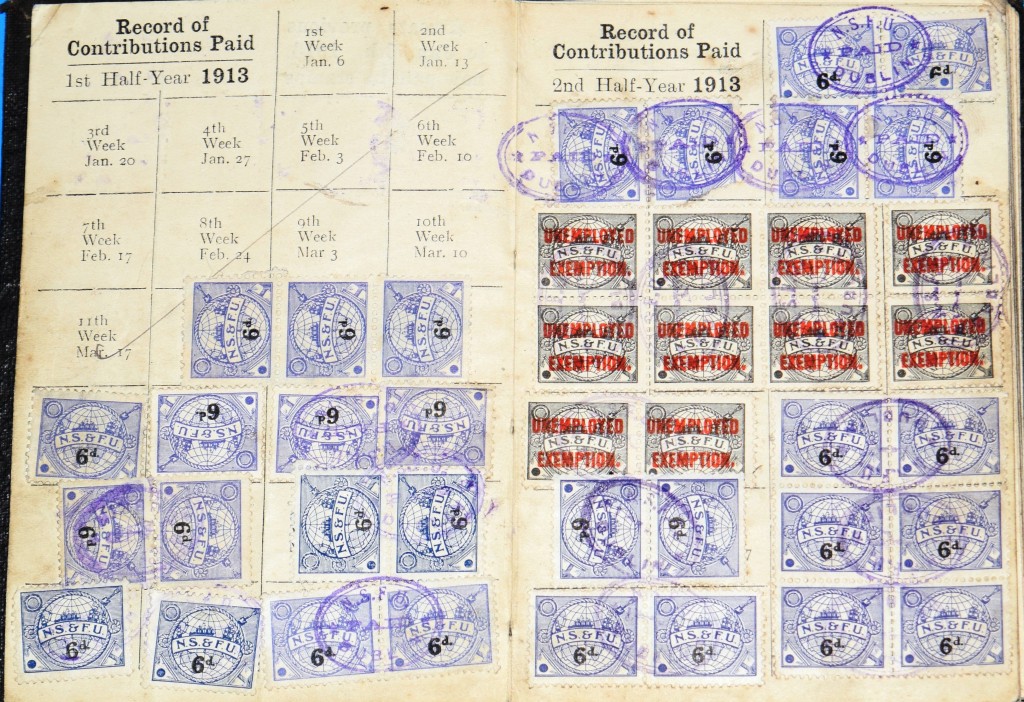

(Photo of Christopher Wolfe and trade union card courtesy Shay Wolfe and family)

Aug 05

Historical Trees , Fairview Park & the Irish Forestry Society

“…turn unsightly districts in town and country into places pleasing to the eye and most conductive to health.”

As a campaign to prevent the destruction of a large number of trees along Fairview Strand gains widespread community support , Hugo McGuinness of the East Wall History Group tells the story behind the original planting and illustrates their importance both in local and national history .

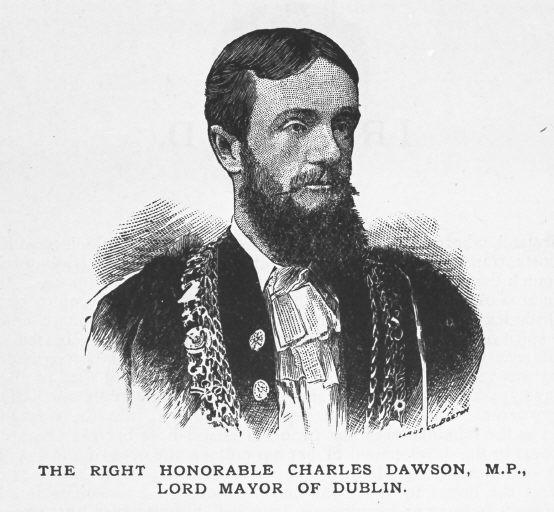

In the 1880s Dr. Robert D. Lyons, MP, commissioned a Professor Howitz, a renowned Forest Preserver from Denmark, to report on the possibilities of using waste land in Ireland to grow trees. Lyons had been compiling information on Irish Forestry for some years and he presented Howitz’s report to Parliament in 1884 which was then quietly set aside. The report proposed planting a quarter of Ireland’s landmass (in a somewhat fanciful but impractical plan) at the rate of 100,000 acres a year for ten years which would cost over £2 million. The plan coincided with a project driven by Father Flannery, Parish Priest of Roundstone in Connemara, who persuaded the Congested Districts Board to plant over 1000 acres near Knockboy, Galway, at a cost of £10,000. It was a disaster and became known as the Knockboy fiasco in government circles as almost all the trees, planted over a ten-year period, died. While the parliamentarians weren’t impressed by Howitz’s report, other people were, and among them was Charles Dawson, Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1883, and in later life Controller of the Rates Office in Dublin Corporation. Among the many notable achievements of Dawson’s tenure as Lord Mayor was the first planting of trees on O’Connell Street.

By the early 20th Century it is estimated that there was just 301,000 acres of forest in Ireland. Much of this was ornamental, a legacy of the great private estates of the 18th Century. Some timber was grown for commercial purposes but this was declining at the rate of about 1000 acres per year. Between £20-28 million worth of timber was being imported into Britain and Ireland annually from Scandinavia, Russia, France, Germany, Canada, and the USA. Stocks in these countries were declining, despite vibrant replanting programmes, and with it came an increase in the costs of imported timber into Ireland at the rate of about 3% each year which was hampering the competitiveness of Irish artisans and manufacturers using wood.

In 1902, Robert Thomas Cooper, a successful London based Doctor, founded the Irish Forestry Society (IFS). Cooper, originally from Co. Carlow, was an enthusiastic believer in the healing powers of plants, his obituary stating that he saw vegetation as the “medium for protecting man from calamities of all kinds,” and it was said that “the national neglect of forestry was to him a source of the deepest pain.” He also believed that much of Ireland’s agricultural poverty came from the deforestation which had taken place in the previous centuries. Unfortunately, Cooper died the following year from influenza, and although his replacement as President of the IFS, Lord Courtown, was highly capable, it was the Secretary of the Society, Charles Dawson, who would become the driving force of the organization.

There were few real experts among the early members of the Irish Forestry Society. Dawson, for example, ran a successful chain of bakeries until he took the post of Controller of Dublin Corporation’s Rates Office, and others included owners of large landed estates, scholars, enthusiasts, politicians, and amateur gardeners. However, they did win over T.P. Gill, Secretary of the newly created Department of Agriculture, and a strong advocate of Forestation in Ireland. In 1907, he was appointed Chairman of the Department’s Commission on Forestry. What they lacked in expertise they made up for in enormous dedication and enthusiasm, and perhaps more remarkably, were willing to put their political allegiances aside for what they saw as the greater good of the country. Dawson sat as a Home Rule MP for Carlow in the 1880s while Lord Courtown was a Unionist who sat in the House of Lords.

There were few real experts among the early members of the Irish Forestry Society. Dawson, for example, ran a successful chain of bakeries until he took the post of Controller of Dublin Corporation’s Rates Office, and others included owners of large landed estates, scholars, enthusiasts, politicians, and amateur gardeners. However, they did win over T.P. Gill, Secretary of the newly created Department of Agriculture, and a strong advocate of Forestation in Ireland. In 1907, he was appointed Chairman of the Department’s Commission on Forestry. What they lacked in expertise they made up for in enormous dedication and enthusiasm, and perhaps more remarkably, were willing to put their political allegiances aside for what they saw as the greater good of the country. Dawson sat as a Home Rule MP for Carlow in the 1880s while Lord Courtown was a Unionist who sat in the House of Lords.

The IFS saw their main aims as educational and to lobby parliament. It was 1904 before they planted their first trees at the Spa Hotel in Lucan and the Phoenix Park as a symbolic gesture which they hoped would lead to the creation of an Irish Arbor Day. They organized demonstrations at annual events such as the RDS Spring Show and Cork Exhibition as well as excursions to forested estates of native Irish Trees. In 1905, they ran competitions with a £5 prize for the best essay on how each of Irelands four provinces could be reforested. In 1906, they had demonstrations and plantings at the Irish School of Gardening for Women at Terenure, the members of which included the wives of many prominent business and political leaders in Dublin. They had lobbied the Government in April that year and been told by the Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell, that they should concentrate on showing “what could be done, the way in which it could be done, and the prospect of remuneration.” Birrell was very much in favour of their activities and agreed that much could be achieved to alleviate the chronic unemployment in Ireland through tree planting. However, he pointed out that much “scientific work” needed to be done before the Government would commit to a national programme. He also admitted that he feared that the native supply of timber would run out within the next 30 – 40 years. Apart from its use in construction, wood was an important source of fuel in certain parts of Ireland and if the country was to rely solely on imported wood the effect on inflation could be disastrous. He said he was always struck by the barrenness of the Irish Landscape when travelling through the country but acquiring the rights to land for planting would always be a stumbling block due to privately held grazing and turf-cutting rights.

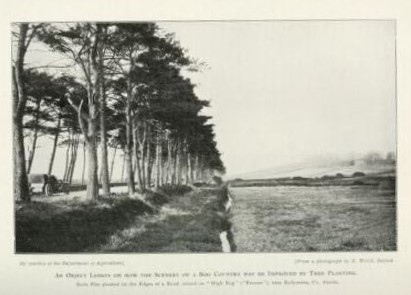

It’s difficult to imagine just how bare Ireland was at the beginning of the 20th century. Newspaper commentators of the time noted that Ireland was “a country denuded of timber, a saddened spectacle … from the bare, unsheltered tracts where woods and forests at one time flourished, represented a commercial loss as well as a scenic deficit.” Another writer noted how “bare places, unsheltered places, ugly places,” could through tree planting, “turn unsightly districts in town and country into places pleasing to the eye and most conductive to health.” The Department of Agriculture had suggested that up to a million acres of waste or poor land in Ireland could be turned into forest. Taking up the challenge the IFS hoped that in setting up a National Arbor Day they could help to achieve this. They settled on the first Saturday in November as the chosen day, although Ulster counties, in a fit of patriotism, decided to pick the 17th March as an alternative.

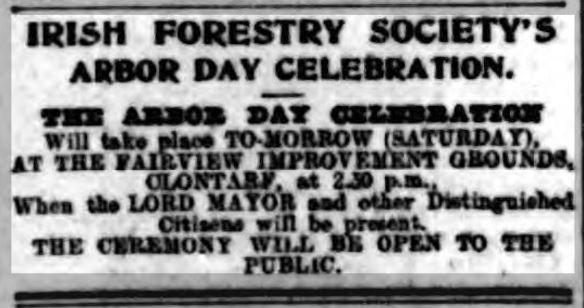

Starting in July 1908, the Society held a meeting with Dublin Corporation at which it was agreed to allow them plant trees at sites such as the new reservoir. IFS members then travelled the country, persuading the various Corporations to pass a resolution calling on the Lord Lieutenant to support the institution of National Arbor Day. Charles Dickson, whose family ran extensive nurseries throughout Dublin and Belfast, donated 6000 trees, with the provision that many be used to educate children and be used in child orientated planting events. F.W. Moore, Director of the Botanic Gardens, claimed children must be taught that trees were living things and be warned of the “wickedness of breaking the bark, breaking the branches, and otherwise mutilating them.” Dawson was aware that they needed national publicity and as they neared the appointed day, (actually Saturday the 31st October that year), an inspired idea was developed.

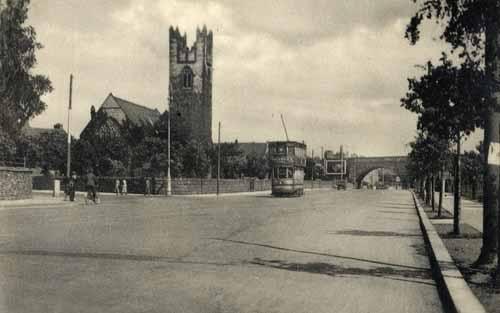

When Clontarf township was absorbed into Dublin Corporation, one of the agreements was that a public park would be developed on what had been knows as the Fairview Sloblands; waste mudflats created by the coming of the Great Northern Railways in the 1860s. Reclaiming the land had been ongoing and as part of the process, the Sloblands, now known as the Fairview Improvement Grounds, were being used as the City Dump, the Corporation charging 3 pence per load of private waste. The smells from the sloblands upset many Clontarf residents with several business owners claiming that their livelihood was being affected. Many felt that the slow progress was caused by the money the Corporation Cleansing Department received from privately dumped waste so a coalition developed between Clontarf and Fairview residents and the IFS to make a very public demonstration through tree planting. Talks were quickly held with the Corporation Cleansing Department who offered their full assistance, and a plan to plant six trees named after the six Corporate Borough Cities, Dublin, Belfast, Cork, Limerick, Derry, and Waterford was formulated (under the Local Government Act Galway wasn’t a city). The idea caught the public’s imagination and the ceremony received an extraordinary amount of publicity in both National and Local press.

As the day drew near disaster struck as Clontarf experienced a serious outbreak of Typhoid which many residents put down to the Corporation’s activities at the “Improvement Grounds.” Around 150 were struck down with the fever and at least 11 died. Nonetheless, the ceremony went ahead with Sir Charles Cameron, Chief Medical Officer of the Public Health Department of Dublin Corporation, planting the “Belfast” tree. In reporting the event later that week the Belfast Newsletter noted that there had been no further outbreaks of the fever at Clontarf. The Lord Mayor, Gerald O’Reilly, planted the “Dublin” tree and expressed the hope that in the future “it would not be shifted from the spot where it was planted.” The sequence of five was completed by other luminaries such as T.P. Gill of the Department of Agriculture, and then fifty trees were planted by local dignitaries such as Dr. J. L. Morrow, Minister at Clontarf Presbyterian Church, Fr. James Brady, and Fr. Denis Petit, local Roman Catholic Parish Priests, and Rev. W. J. Lumley, Rector of St. John the Baptist Church on Seafield Road. The former Lord Mayor and IFS Secretary, Charles Dawson, stated that not only would the trees being planted at Fairview assist in the battle against the “scourge of consumption”, but he noted that many of those involved in the ceremony “worship at different alters” yet it showed that it was “in the power of all creeds and classes to join together and do something for their common country.”

Similar events took place at Portumna, Doneraile, Blackrock, and Sandycove, with demonstrations organised later in the week at local Dublin schools to show the process and benefits of tree planting. Fr. James Brady, apparently a serial tree planter, provided the demonstration involving local school children at St. Laurence O’Toole’s at Seville Place the legacy of which is those fine mature trees still there today. They were probably the first trees planted in the North Docklands for 200 years. As Fairview caught the imagination, Sir Hugh Lane, then in Spain on business, telegrammed the Board of Guardians at the North Dublin Union simply stating plant trees and send me the bill. The Gaelic League, together with local Unionist landowners at Ardagh, Co. Kerry, set their politics aside to organized an extensive planting in that town around schools, churches, and other public buildings, under the banner of La na gCrann, with many other events taking place in the subsequent weeks involving over 300 National Schools throughout the country. The Mayor of Limerick planted a Lime Tree near Island Bank and hoped that the entire area with be tree-lined in the coming years. Limerick Corporation then announced a plan to plant 150 trees throughout the wards of that city. Then the Irish National Foresters Benevolent Society offered the assistance of their nationwide membership with the organizing and implementing of future tree planting projects. The final event was the planting of 150 trees at the Dublin University Boat Club at the end of November. Most importantly, the publicity organized around the Fairview planting allowed T.P. Gill’s Committee to report to Government that the scheme they were proposing “had the approval of the whole public.” Remarkably, Government funds were made available for a reforesting programme, leading A.C. Forbes, manager of the Forestry School at Avondale from 1905, to claim that despite their naivety and “utopian view” the IFS “was probably responsible for State Afforestation being inaugurated in Ireland.” It was the first programme of its kind in Britain or Ireland.

Fairview had been a small first step by the IFS. Residents of Fairview and Clontarf saw it as an opportunity to lay down a marker of how they wanted their park to develop. In recalling the event the following year, a writer in Irish Gardening magazine questioned what it had achieved other than providing an opportunity for speech-making, although they did admit that it was near impossible to get a shovel in Dublin as a tree planting mania had erupted. Another writer sarcastically noted the regular visits of the great and the good of the political world to The Improvement Grounds to inspect the trees and speculate on how the parklands might develop. In truth, while a park had been discussed it was unclear exactly what use the reclaimed lands commonly known as the Fairview Sloblands would be put to, or how much of the land would be set aside for a public park. The actions on the 31st October 1908 certainly pushed things in favour of the creation of modern day Fairview Park, one of the jewels of the present-day Dublin City Council Parks Service. The following year, local landowner, Thomas Picton-Bradshaw of Mount Temple, donated a large number of trees and shrubs for a similar event at Fairview on Arbour Day 1909 to be planted between Annesley Bridge and the Malahide Road. One writer noted that the passer-by “can now see the promising beginnings of a growth that should give ample and graceful decoration to the park of the future.”

As the Fairview planting caught the public imagination many counties began to ask why they didn’t have similar events. The Lord Lieutenant and his wife, Lord and Lady Aberdeen, agreed to plant trees at Bray in 1909. The IFS were invited to make presentations at various Government enquiries and commissions, showing statistical and practical examples of the potential use of trees in Ireland for both commercial and health benefits. Slowly the wheels turned in their favour. In his address at that 1908 ceremony, Charles Dawson stated that the object of that day’s exercise was to “make a demonstration with a view to compelling the Government to undertake the work of re-afforesting Ireland. The people could not do it; but the Government could.” Large tree planting schemes were set up by the Government from 1911 onwards, only briefly interrupted by the Great War in 1914. Grants were instituted, and in 1919 during the War of Independence, the Dail adopted reforestation as policy.

It would be 1934 before Dublin Corporation formally adopted a set of bye-laws which would make Fairview Park a reality. But back in 1908 the influence of those embryonic steps of the Irish Forestry Society, together with the local clergy, business, and political community, was far-reaching. As you stroll around Fairview and Clontarf, and look at those numerous mature trees in churches, schools, and gardens, it’s difficult not to speculate how many were planted in the aftermath of Saturday 31st October 1908. The week after those trees were planted, Dr. John Love Morrow, presided at a meeting at Clontarf Town Hall to deal with the Typhoid Outbreak. He told the audience that they were tired of Unionist Associations, tired of Nationalist Associations ,tired of Sectarian divisions. They were there as Citizens of Clontarf and together they would decide a course of action which was best for all the Citizens. The lesson of the previous week had been well learned. A Clontarf Improvement Association was founded soon after and was vocal in promoting the Citizens wishes, particularly in relation to their park.

Alderman Healy, Alderman Crozier, Charles Dawson (IFS), Rev. Dr. J.L. Morrow (Clontarf Presbyterian Church), Alderman Gerald O’Reilly (Lord Mayor), T. P. Gill (Dept. of Agriculture), Sir Charles Cameron, Alderman Woodhead, Dr. M’Walter, planting trees at Fairview, 31st October 1908.