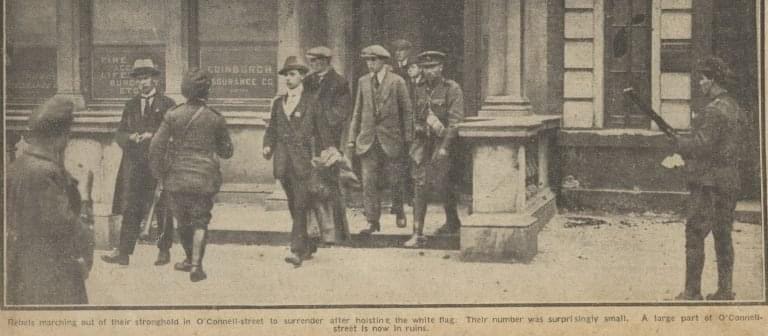

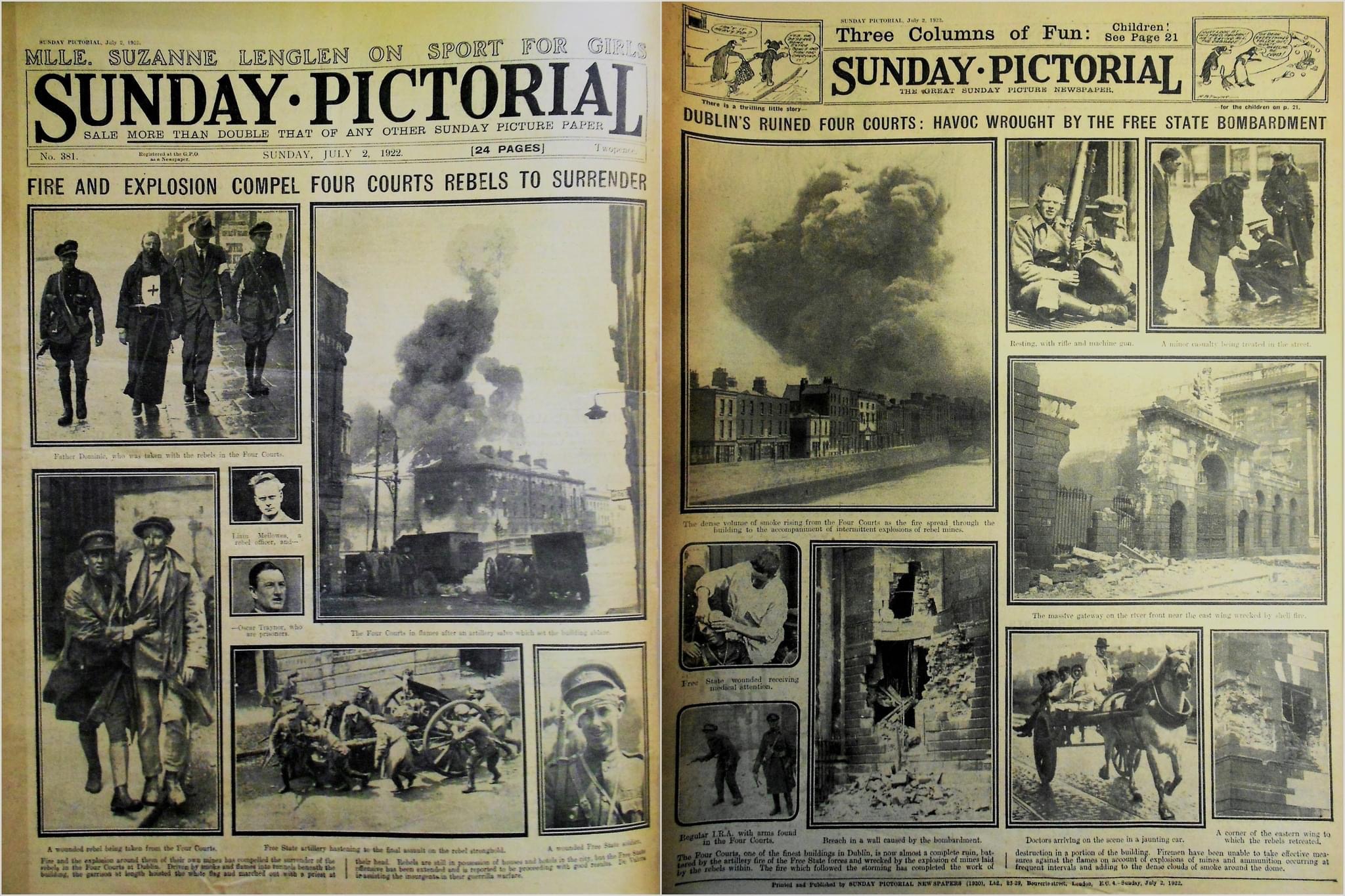

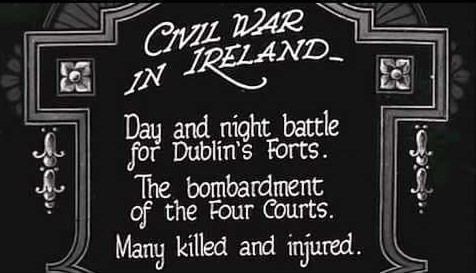

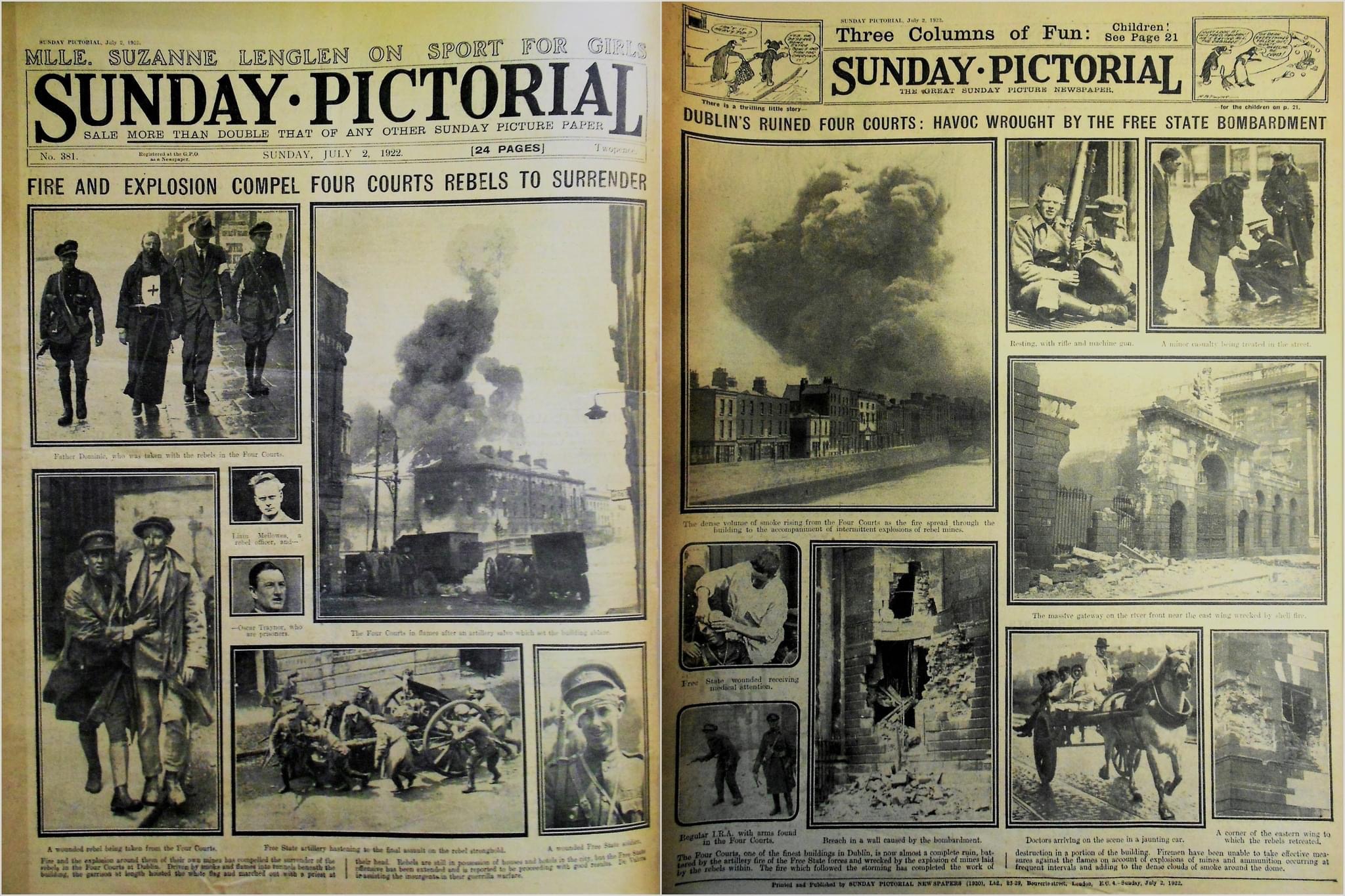

Just over a hundred years ago, the shelling of the Four Courts signalled the start of the Civil War. As the so called ‘Battle of Dublin’ raged, the capital’s main thoroughfare was once again in flames. For the second time in just over six years, Sackville Street (now known as O’Connell Street) was once again a battlefield. The now familiar sounds of gunfire, booms of explosions and cries of the wounded echoed through the buildings and streets of the capital.

The anti-treaty Republican forces, who had occupied a series of buildings at the North/East end of Sackville Street were now surrounded by the pro-treaty National Army. On the 5th July 1922, the battle was reaching its climax – the buildings were an inferno, flames reached to the sky and smoke billowed through the surrounding streets and lane-ways.

With no regard for his own personal safety, a lone civilian made his way through the chaos, plunging through the smoke and dust in a desperate attempt to gain entry to the buildings. Eventually, he was ordered away by firemen due to the increasingly dangerous conditions. Within hours of this incident, the battle had ended and as the buildings crumbled, so too collapsed this man’s hope of a peaceful solution to the conflict, a peace he thought he could help broker.

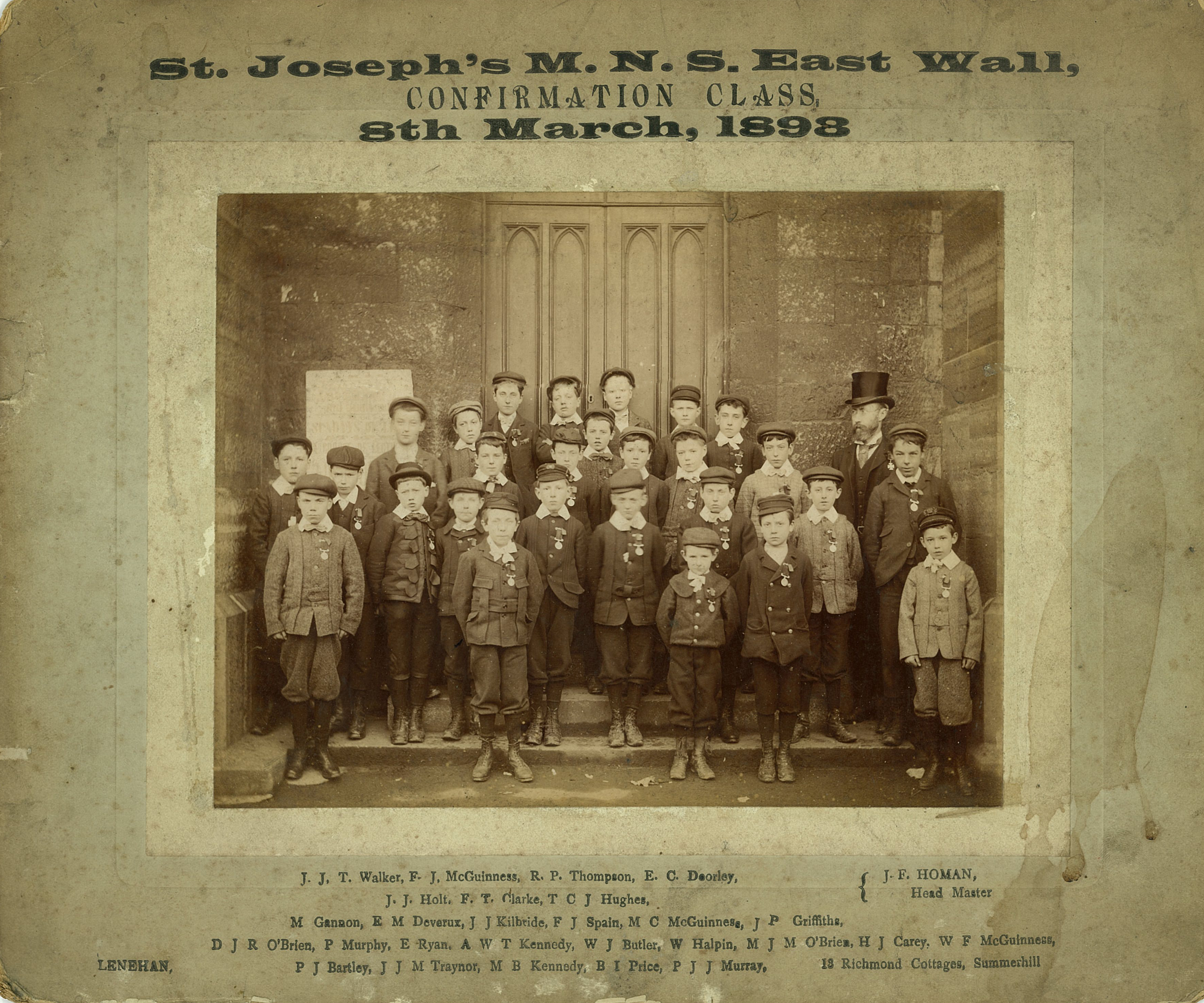

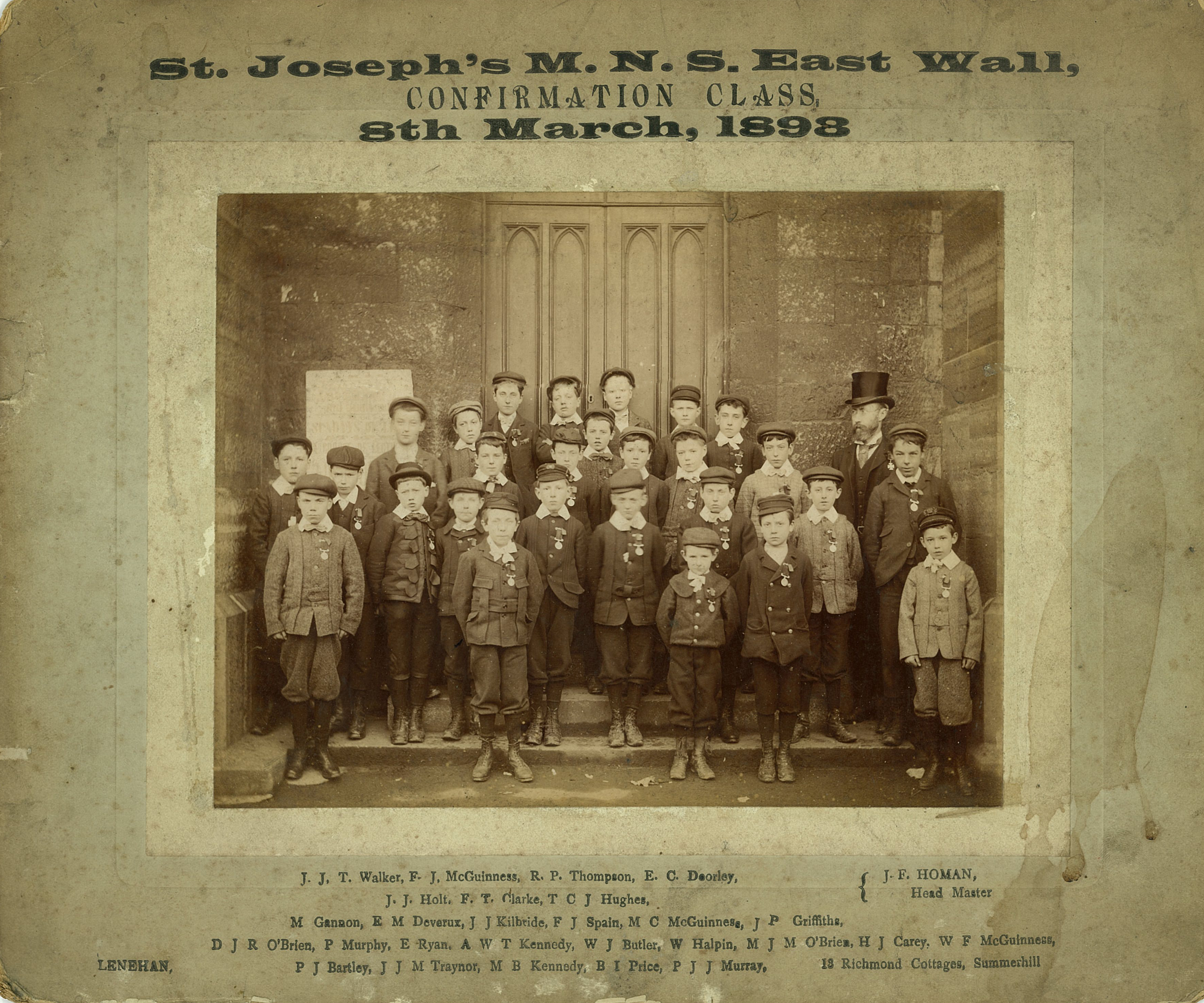

The man was no other than John Francis Homan, a decorated volunteer in the St John’s Ambulance Brigade and also the long-serving principal of the East Wall Boys’ School in the North Docks. This is the story of an ordinary man who found himself caught up in extraordinary events, not only during the outbreak of the Civil War, but also throughout his life.

A man of Principal :

John Francis Homan was born in Cork in approx. 1864. After qualifying as a teacher, he held a position at a private school in Kilkenny. In 1895, a new convent school opened in Dublin’s North Docklands on the Wharf Road (now East Wall Road). It was a moderate sized, single-story building with the open sea just across the road. The school comprised of an infant school and separate boys’ and girls’ sections. J.F. Homan became the first principal of the school, a position he maintained until his retirement in 1926. According to the census records of 1901, he was living almost adjacent to the school at Seabank House and was a boarder with the Kavanagh family, who were proprietors of the pub on the corner.

On the 15th August, 1905, John Francis Homan married Mary Mullholland, also a teacher, in the Chapel of St. John’s, Clontarf and his father is listed as Eyre Coote Homan (of the Mallow Cootes). By 1911, he was living at 2 Beechfield Terrace, Clontarf and had been married for five years. On the census record, he describes himself as an undergraduate of the National University of Ireland and Principal of a National School and a private college. This private college was The Homan & Allen Private College which was based at Harcourt Street and prepared young men for the entrance exams for teacher training colleges.

By all accounts, he was a passionate and intelligent educator. He also appears to have been head-strong, opinionated and given the standards of the time and place, he was probably judged unconventional if not eccentric. His decades as principal were not without controversy or conflict (the 1911 schoolboys’ strike being a prime example) though it is clear from local recollections that he was well liked by many past pupils. His time in the school will be explored later in this article.

He was a well-travelled man. In fact, an obituary published in the United States on his death stated, “he was an accomplished linguist and an authority on Arabic dialects.” Another indication of his extensive travels was an ‘unexplained’ absence from his teaching duties in 1905 which was later explained when he published in an education journal, an account of a trip he took to Japan. Additionally, during the Great War, he arranged a private trip to the battlefields of France. This latter trip may have been due to an interest in wound-based medicine, as for many years, he was a volunteer in the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade.

John Francis Homan

“…they treated casualties on both sides and fed and cared for evacuees”.

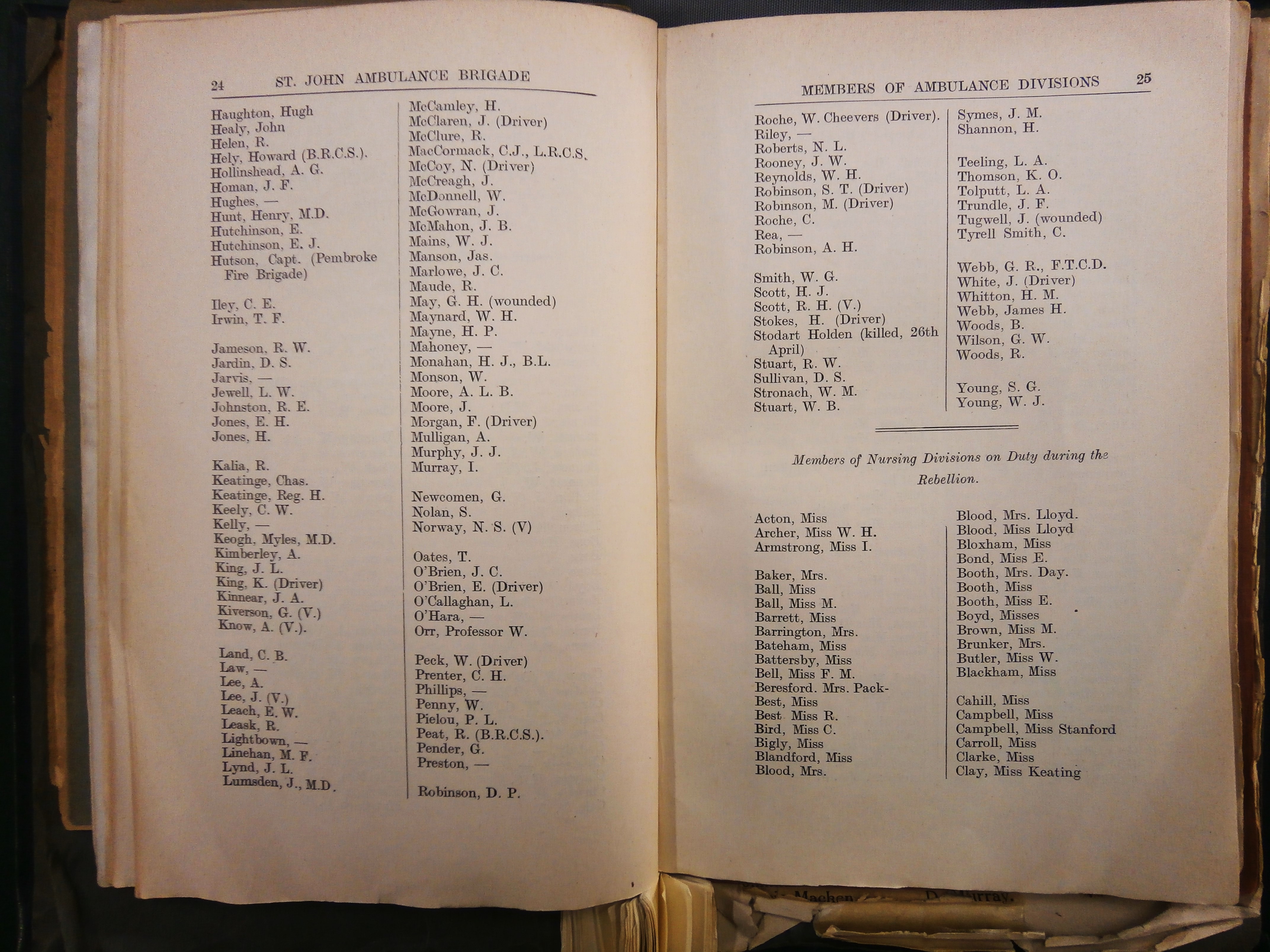

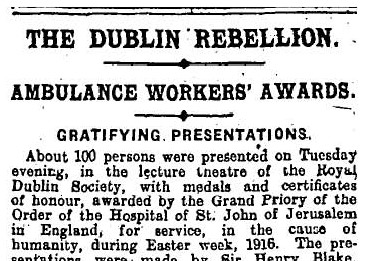

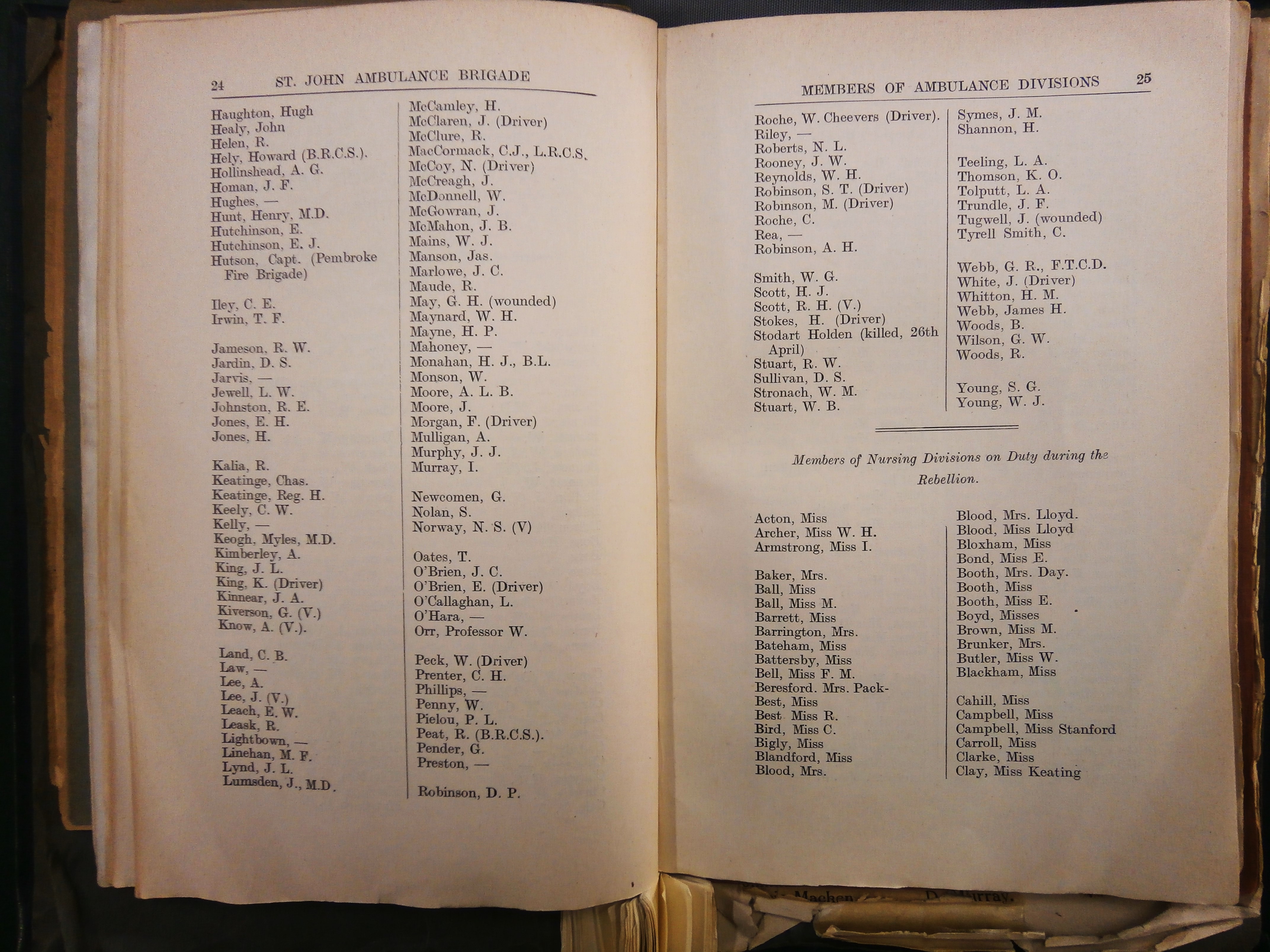

J.F. Homan was a dedicated member of the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade. The Brigade itself had been founded in 1903 by Dr. John Lumsden (chief medical officer of the Guinness Brewery). According to Pádraig Allen, a volunteer and archivist/researcher with the Brigade:

“The membership leading up to 1916 swelled, with 1,182 men and 1,592 women in the ranks of the organisation. The organisation spread across 20 counties of Ireland with the majority of members, about 1,300, in Dublin. Many of the divisions invested in motorised ambulances, replacing some of the horse-drawn wagons…. During the Easter Rising 600 members of St John Ambulance – of which close to 500 have now been named – turned out onto the streets. They provided 15 motorised ambulances with assistance from the Irish Automobile Club (now RIAC), horse-drawn ambulances, female nurses and men to staff the hospitals and stretchers-bearers to pick up the wounded and dying.”

“A total of seven auxiliary hospitals were set up across the city. Men, women and children were operated on and those hospitals filled quickly with the wounded … they actually took wounded out of the city hospitals and transferred them to the hospitals that were set up… Each hospital had a medical team and stretcher bearers to bring in the wounded. Children as young as 12 were treated at these hospitals – some had been shot and others had to have limbs amputated in an improvised operating theatre.”

During the rebellion one member of the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade was killed and ten more were injured as they tried to retrieve the wounded from the streets. It was said afterwards that they “earned the respect of all sides of the community during the Easter Rising of 1916 as they treated casualties on both sides and fed and cared for evacuees”.

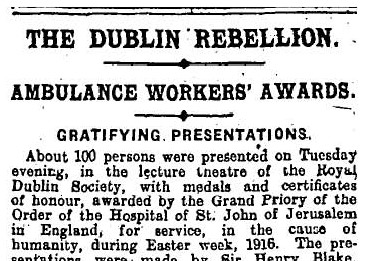

Homan was on active duty during this period, and months after the insurrection, he was among one hundred Brigade members who were honoured for their role ….

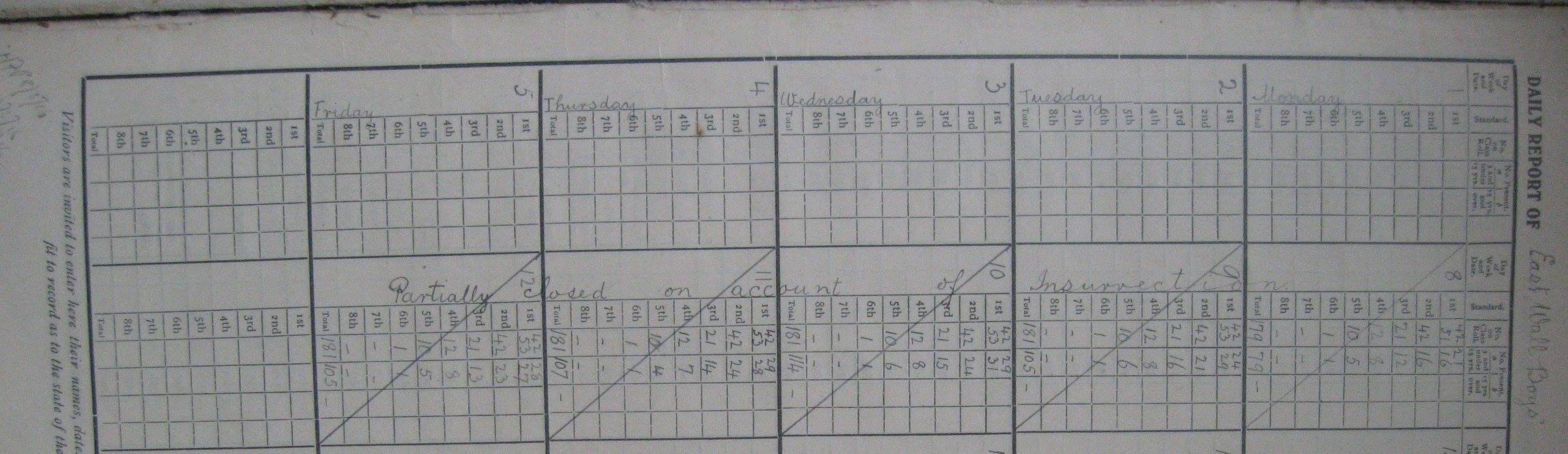

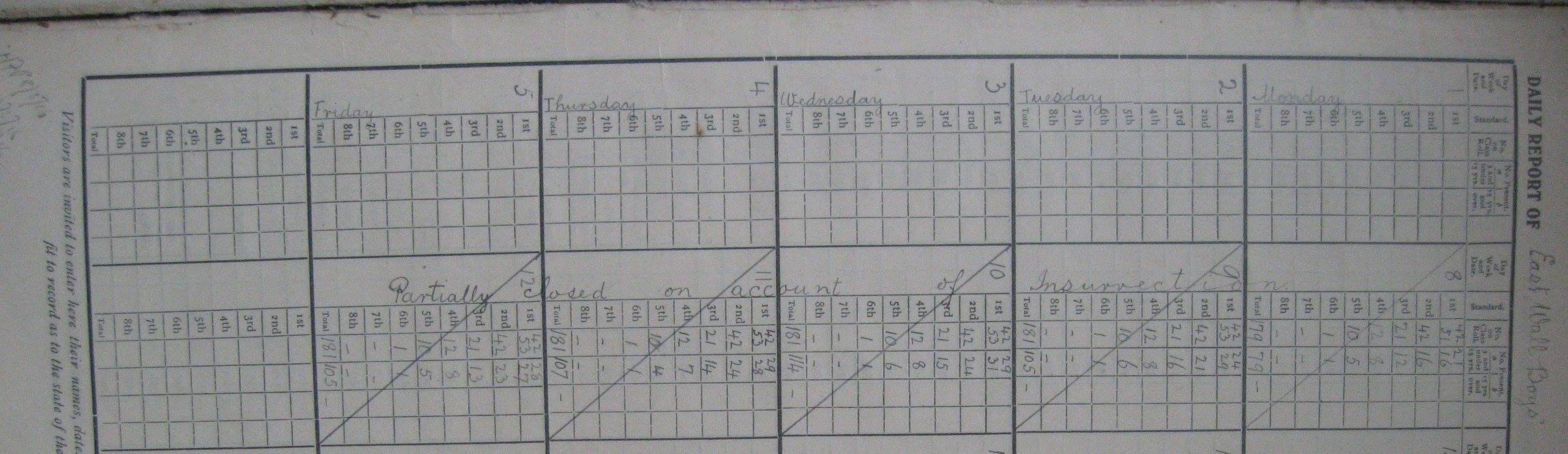

It is also interesting to note that Homan did not need to fulfill his role as school principal during this period , as the school records show that they were initially on Easter holidays and subsequently closed for extra days “due to insurrection”.

School register 1916

“Between two Hells…” a most un-civil war begins :

Aside from his own Easter Week experiences, like most people during this period, he was intensely aware of the revolutionary or progressive sentiments of the times. He was an advocate for the Irish language and an intriguing postcard (dated 1900) is a reminder of an arranged meeting with Eamonn Ceannt (1916 Proclamation signatory and one of the executed leaders). In fact, many of his past pupils and their families, and even some of his staff, were directly involved in the events of Easter Week and afterwards. The 1898 confirmation group photograph from St. Joseph’s, East Wall, includes a young Willie Halpin who fought at the City Hall Garrison with the Irish Citizen Army. Irish Volunteer and future senator Sean T. Ruane was also a trainee teacher in the school under Homan.

Between January 1919 and July 1921, the War of Independence or ‘Tan War’ engulfed the country, and again, many locals were involved. The school itself was once again affected, as this record from April, 1921 illustrates. It states that the school was “closed due to Crown Force raids”. This was the day of the IRA attack on Auxiliaries based at the LNWR Hotel on North Wall Quay. A truce was agreed in July of that year which saw a cessation in hostilities as Irish leaders and British politicians engaged in intense negotiations.

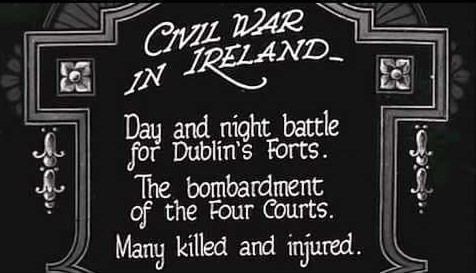

These negotiations led to the Treaty debates which, in turn, led to a fracturing of both the political and military unity of the Irish revolutionary movement. As tensions mounted between the pro-treaty Free State / National Army and the anti-treaty Republicans/ IRA, desperate efforts were made to avoid escalation. Republicans had established their executive in the occupied Four Courts complex of buildings. Under mounting pressure from Winston Churchill and the Westminster Government, the National Army launched an attack on the Four Courts. Using 18 Pounder guns loaned by the British Army, at 4.20am on Wednesday July 28th, the shelling of the Republican headquarters commenced, heralding the start of the Civil War. The offensive sparked the weeklong “Battle of Dublin”.

The Battle of Dublin :

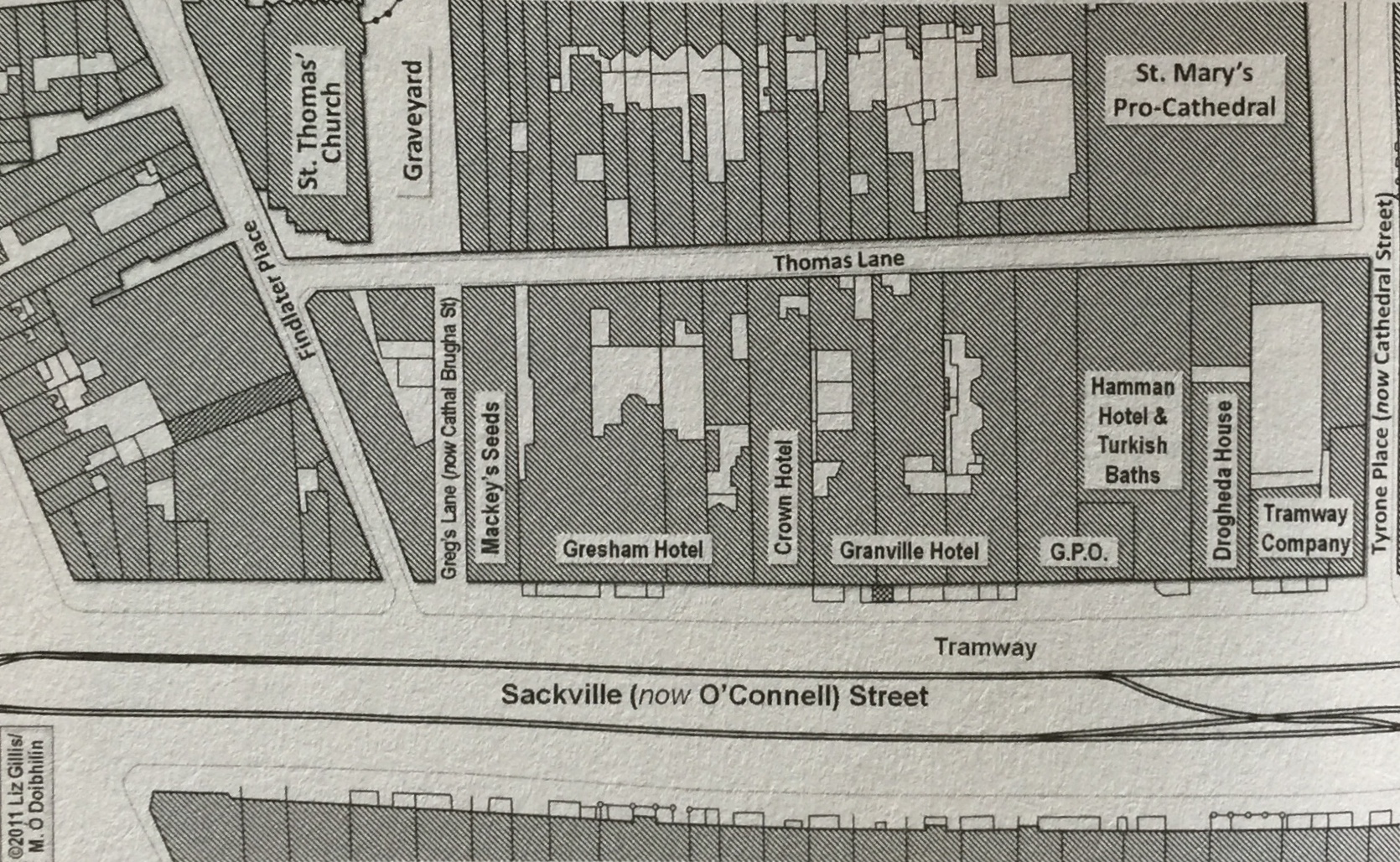

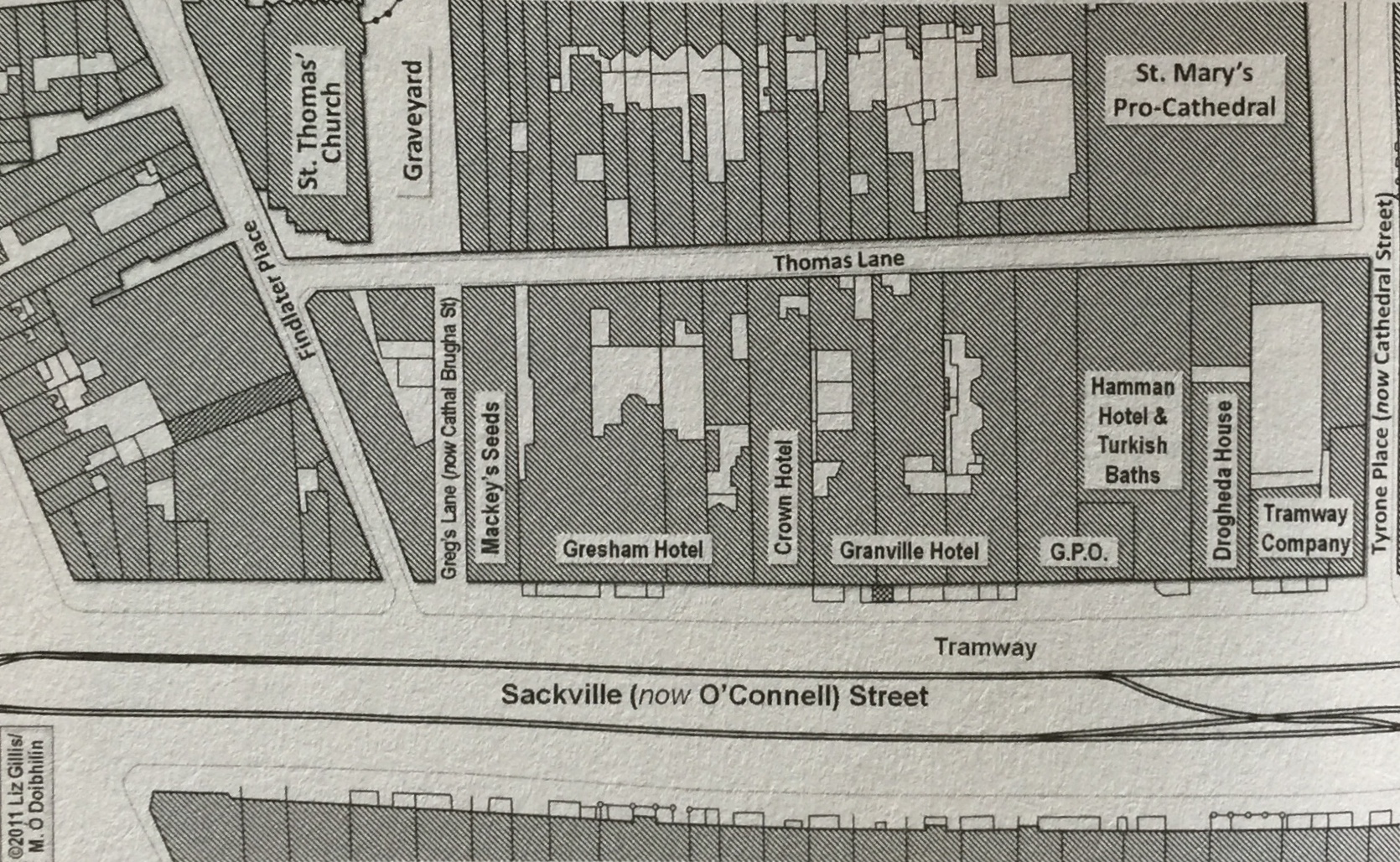

The bombardment of the Four Courts was intense though relatively short lived. By Friday afternoon, with no effective response to the heavy guns of the National Army forces possible, the 140 strong Republican garrison surrendered; however, intense fighting elsewhere in the City centre continued. Once the bombardment of the Four Courts had commenced and open conflict was inevitable, the IRA mobilized. Efforts to take pressure of the Four Courts began and Republican forces seized and occupied buildings on the North Eastern section of Sackville Street, the capital’s main thoroughfare. Within the adjoining buildings, interior walls were broken through to connect them (much like what had happened on Moore Street in 1916) and this soon became identified as ‘the block’. The premises occupied included a number of hotels – the Gresham, the Granville Hotel and the Hamman. Key republican figures including Oscar Traynor, Eamonn de Valera and Austin Stack established their headquarters here while Cathal Brugha was appointed commandant of the ‘Block’. Their forces consisted of approximately 120 men and women, composed of members of the Irish Republican Army, Cumann na mBan and some Irish Citizen Army.

- The Block

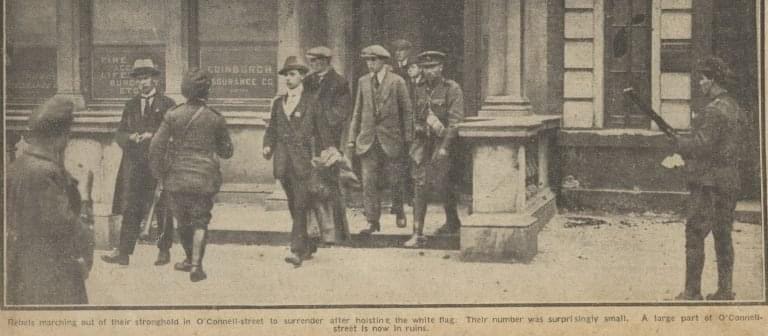

With the surrender of the Four Courts, the National forces were able to concentrate on ‘The Block’. Other outlying city centre positions held by smaller republican groups were gradually over-run, and under the command of Tom Ennis, all efforts were focussed on the ‘The Block’. By Monday evening, faced with overwhelming firepower from rifles, machine guns and armoured cars, the Republican position was hopeless. The order to retreat was given and Traynor and DeValera (along with 70 men and 30 women) managed to withdraw, planning to make their way across to the south side of the city. A rear-guard under the command of Cathal Brugha, remained to cover their retreat. Despite the imbalance of forces, the efforts to dislodge the remaining republicans would still prove difficult.

As the Irish Times reported:

“Gunners appeared to pick out particular objectives in the hotels, upon which they poured a withering fire, which was occasionally returned by the garrison. Machine guns were brought into operation, while smoke bombs and grenades were frequently hurled by the attackers”.

Throughout Tuesday, and into Wednesday, the assault continued with field guns brought into position. By Wednesday evening, the sustained barrage had caused several fires to break out and ‘The Block’ was ablaze. The roofs began to give way and the entire buildings were in danger of collapsing. The fire brigade had strived valiantly all week, despite the dangers posed by the combat, but the situation was proving impossible to control. At 7 p.m., on Thomas Lane (at the rear of the Block), shouts of surrender were heard and the garrison of approximately 20 people emerged waving a white flag. These were taken prisoner. Cathal Brugha had ordered the surrender but had not taken part. A short time afterwards, he emerged, and wielding two revolvers, ran down the lane where he was shot and fatally wounded. He died two days later at the Mater Hospital. The volley of shots which had rang out effectively signalled the end of “The Battle of Dublin”. It was into this chaos that J.F. Homan had stepped in to the smoke-filled streets on his desperate mission of peace.

Efforts for peace

We are extremely lucky that J.F. Homan recorded the events of this period, and of his own activities, during the battle. We are most grateful to Dublin Diocesan Archives and South Dublin Libraries for making this invaluable document available to us.

He begins:

“My Ambulance duties in connection with the Civil War began on Wednesday, the 28th June, and continued until the Saturday following. My work was varied. At one time I had charge of the S.J A.B. party at the hut opposite the Hammam Hotel; at another, of the party at the Metropole Cinema; much of my time was spent going round with Mr. Bentley in his improvised ambulance car. During one of my journeys with him, on Thursday evening – to the Insurgents; dressing station at the rear of St Kevin House, Parnell Square, to remove a dead man and a wounded man – the Insurgents seized the Hamman, into which we had just transferred the contents of the hut for the night. On our return we found the guests very excited and frightened. Much anxiety was felt particularly for an aged and delicate Catholic prelate Bishop O’Reilly, of Peoria Illinois, who was suffering severely from the shock. We brought his lordship in the ambulance to the Shelbourne hotel. On the way to cheer him up, I talked as pleasantly as I could; and before we parted we were already good friends.”

The devastation on Sackville Streetr (O’Connell Street)

“On Saturday… before reporting for duty I went to the Shelbourne to enquire for Bishop O’Reilly. I found the Bishop recovered from the shock, but still very feeble. In the course of conversation, he described his meetings with Mr de Valera and Miss Mary MacSwiney in America and of his friendship for them both. It occurred to me that his influence might prove a useful factor in the negotiations for peace and I asked him whether I might mention his name to my Chief in that regard. He at once expressed a strong desire to do anything he could, regretted the feebleness as that confined him to the hotel, but urged me to induce if possible Mr. de Valera and Miss MacSwiney to visit him there.”

From this point on, Homan engaged himself in efforts to reach out to both sides of the conflict (the Insurgents and Provisional Government). He had a long conversation with Capuchin Father Albert who had administered to a number of the 1916 leaders prior to their executions, had been present in the Four Courts and was now at the Hamman. Father Albert was known as a figure who could be trusted, and Homan believed that with assistance from Albert, a neutral approach (via the Ambulance Brigade) could help bring the protagonists together. However, when he raised the idea at the Brigade Headquarters (Merrion Square) concerns were raised. Commissioner Lumsden cautions him that to:

…”visit Mr. Collins on a peace mission would go dangerously near to an infringement of the Geneva Convention and might expose the Brigade to an accusation of taking sides [cnc1] in a military or political matter” .

Homan, however, believed it would be far worse to do nothing when an opportunity for peace presented itself. He tendered his resignation from the Brigade to pursue the idea himself but his resignation was refused and he was advised that if he removed his uniform and donned civilian clothes, he could act as “a simple citizen for whose acts or words the Brigade would be in no way responsible”. Homan returned to Clontarf, changed his clothes and drove to the office of the Provisional Government where he met Michael Collins.

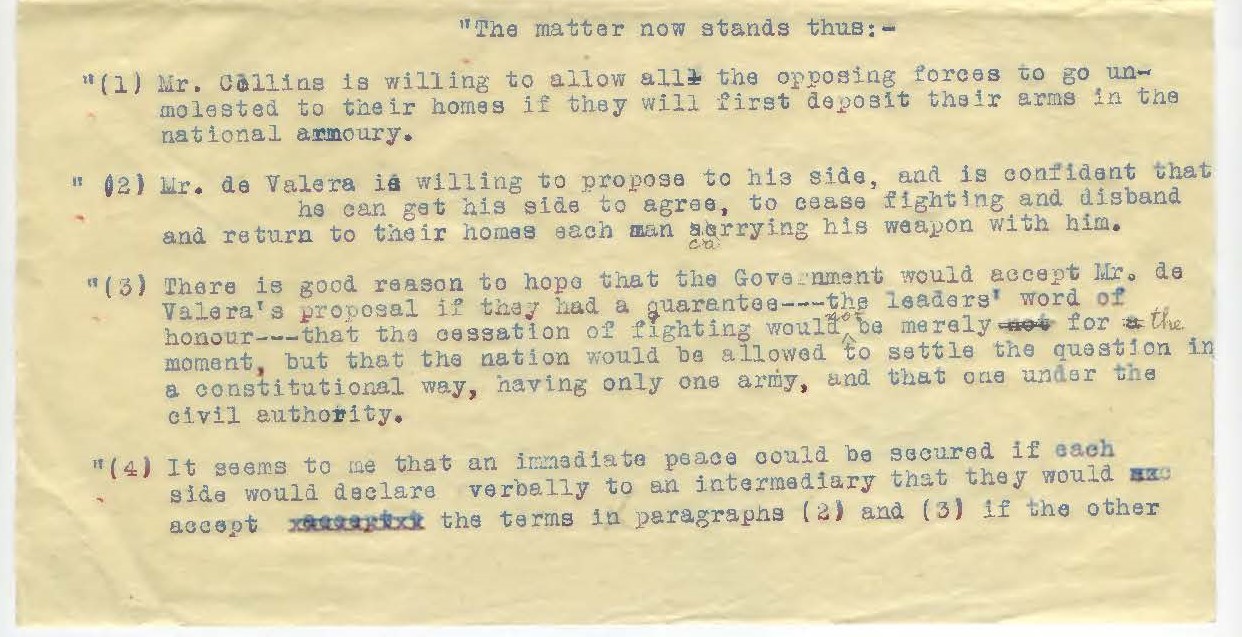

According to Homan’s account of that meeting, he left with a message from Collins that he could:

“Tell these men that neither I, nor any member of the Government, nor any officer in the army (and I learned the feeling of every officer in Dublin on my rounds yesterday not one of us wishes to hurt a single one of them, or even to humiliate them in any way that can be avoided. They are at liberty to march out and go to their homes unmolested if only they will – I do not use the word surrender – if only they will deposit their weapons in the National Armoury, there to remaln until and unless in the whirl of politics these men become a majority in the country, in which case they will themselves have control of them”

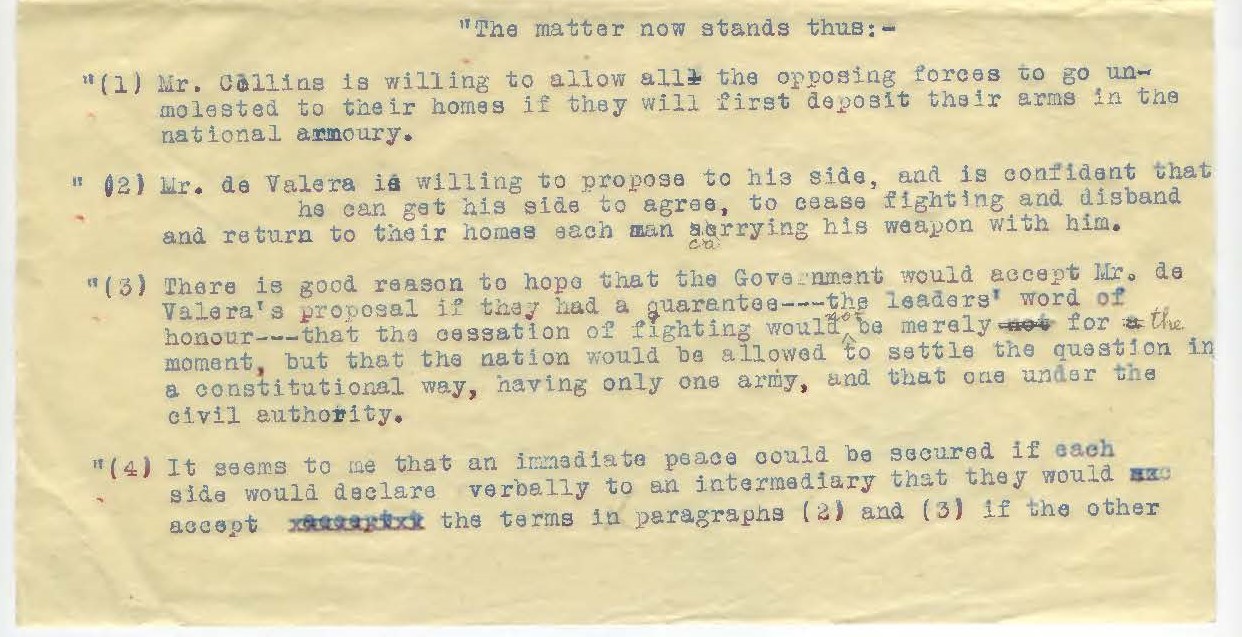

The following day, efforts were made to bring Eamonn DeValera to the Shelbourne Hotel to meet the Bishop but despite a guarantee of safe passage from the provisional Government, he did not comply. Homan himself eventually met with Eamonn DeValera (passed on the Bishop’s good-will) and reported on Collins’ statement. According to Homan, there was a counter suggestion from DeValera :

“He would be prepared to recommend to the Insurgents, and was confident he could get them to agree, to go home each man carrying his weapon with him. To explain the desire to retain the arms he described the love for his weapon engendered in each man by years of fighting. The right to retain his rifle (shared as it was by every other citizen) would do much, he declared, to mitigate the bitterness of present feeling and this appeasement would be more valuable to the Government and to the country than the surrender of the arms.”

Related matters were discussed and Homan was upbeat in his assessment that:

“On the whole we seemed a long step nearer to peace and I parted from Mr. de Valera with expressions of high hope and appreciation”

The following day, a meeting with Collins did not proceed smoothly. He was emphatic that “permission for the fighting men to retain their weapons was not defensible” and in a direct rebuke to Homan “he expressed amazement that any citizen should express approval of such a proposition or allow himself to become an emissary of Mr de Valera in pressing it.”

As Homan himself wrote: “It seemed I could do no more. The situation was deplorably sad” However, he was not prepared to give up and sought out James Douglas who was “chairman of one Government commission and member of another, and an old friend”. His friend listened to Homan’s account of what had transpired over recent days and Homan was encouraged to believe that some agreement was still possible and set out to seek DeValera at ‘The Block’ (though by now, of course, the majority of Republicans had already withdrawn):

- National Army at Gresham Hotel

“I went straight to the Hamman, entering as previously from the lane. A striking change had taken place. The back rooms, which had been full of people, were almost deserted. The faces of most of those remaining were anxious. A doctor, in reply to my enquiry, said Mr deValera was not there. Learning the nature of my mission he advised me to speak with Cathal Brugha, for whom he sent, warning that I might have to wait for some time, for as you can percieve something very exciting has just happened”.

Homan was courteously received but left in no doubt that Brugha was not interested in his proposals:

“I was brief, he even briefer. ‘Lay down our arms.’ said he. ‘Never. We are out to achieve, our object or to die There is no use negotiating with Mr. Collins. What exactly did Mr. de Valera propose’ I told him.’ He could not carry the fighting men with him in that’, said Mr Brugha; ‘The most they would agree to would be to leave this place with their arms and go and join our men fighting elsewhere. And for my part I would oppose even that. You are wasting your time. We are here to fight to the death’.

Despite this clear rejection, his inability to get any agreement between leaders on each side and the worsening situation in the city centre, the next day (Tuesday), Homan was still endeavouring to make progress. He visited his friend James Douglas at his Rathmines home and despite another grim assessment, he felt he could still achieve peace. As his account details: “I learned a great deal, but it seemed very unlikely that I could do any more good.” Despite his inability to broker peace, he insisted on drawing up a memorandum based on discussions of the last number of days:

On Wednesday, he made one last desperate attempt to see De Valera and felt driven to propose the (vague) proposals to a receptive audience:

Valera. Father Flanagan then came on the scene, informed me of Mr de Valera’s departure and took me into the house where I showed him a copy of the memorandum. As the surrender and fall or the insurgents stronghold in O’Connell Street was now a question of an hour or two at the outside, and as it would materially change the situation, Father Flanagan and I agreed that I could do no more”.

And so the story of J.F. Homan’s desperate peace efforts came to an end. This fascinating vignette illustrates that he was a man clearly driven by and committed to the highest of motivations but how likely was he to succeed? While he demonstrated an ability to engage with the key protagonists and could have served as a genuine intermediary, his assessment of the situation at that time was clearly based on emotion rather than fact. His memorandum essentially states two options, neither of which was palatable to the opposing sides, and he had been clearly told this. His mission, praiseworthy as it may have been, unfortunately seems to have been driven by a combination of hope and desperation. While, the matter was out of his hands, it must have weighed heavily on his mind afterwards.

School on East Wall Road (current location of St Josephs Co-ed)

Big in Japan :

The historic events of 1916 and 1922 were not the only extraordinary episodes in J.F. Homan’s life. As principal of the St. Joseph’s Male National School in East Wall, he found himself embroiled in controversy on more than one occasion and certainly banged heads with the school authorities numerous times. In researching the story of the school (locally referred to as The Wharf School) and its staff, we came across several occasions where Homan drew unfavourable commentary from the inspectors, and was, in fact, reprimanded by the manager Canon Brady (parish priest of St Laurence O’Toole’s Church).

The examples of these complaint, documented below, range from 1903 to 1909 :

“Manager Requested to admonish Mr Homan for the impropriety of tone adopted in his letter explanatory of his late attendance”

“Mr Homan did not arrive till 10 o’clock instead of 9.30. Explained he was detained by special private business.”

“Mr Homan late. Progress Record Book very incomplete.”

“Mr Homan reprimanded on repeated irregularity in attendance.”

“Mr Homan did not arrive until 10 o’clock and would give no satisfactory explanation as to cause of his lateness. Manager’s attention drawn to this by Inspector.”

“Manager requested to inform Mr Homan that written evidence of proper preparation for class lessons is essential and will be looked for in future. Teacher makes practically no preparation for class lessons.”

And in 1914 he was:

“…severely reprimanded and warned in regard to general unsatisfactory performance of duty, failure to take a proper share of the school work, defective organisation, and unpunctual attendance”.

In one record, it is noted that he took an unsanctioned leave of absence in 1905. An explanation for this absence was forthcoming the following year when the periodical “The New Ireland Review” published an article entitled “Japanese Schools-Their lesson” by J.F. HOMAN. It was a report on his visit to Japan where he visited to study the education system. He set out from Vancouver Island in May 1905 for a 14-day voyage to Yokohama. Bearing in mind that at this time Japan and Russia were at war, it should come as no surprise that he recounts an incident when “I was at once taken for a Russian spy plotting the escape of prisoners, was arrested, brought before the colonel on the platform, questioned and cross-questioned, my passport examined, and the address on some of my letters carefully scanned and copied.”

During his time there he visited many schools across the country and was somewhat surprised when an official (Head of the Japanese Education Department) turned up to greet him:

“For the first time I blushed. Surely, thought I, there is some error here; they mistake me for somebody! But no. They understood my position well. It is enough for them that I had just come from the Far West to the Far East, and that I was a professional teacher with sufficient enthusiasm to devote to the schools a large part of my time in one of the most attractive cities in the world.”

He commented favourably on the schools he visited and was greatly taken with not just the school buildings but also the methods of discipline, behaviour and curriculum. He was also fascinated by the cleanliness of everywhere he visited. In his paper, he concluded by saying:

“I cannot help envying the Japanese teachers their position of dignity and influence, their quiet class-rooms, the home-like creature comforts of their schools, the frank sympathy of their superiors, and the discipline, earnestness, and affection of their pupils”

Unfortunately for J.F. Homan, most of these attributes he so greatly admired were sorely lacking in his own school in 1911 when his pupils declared a strike.

“THREE BLACK EYES”

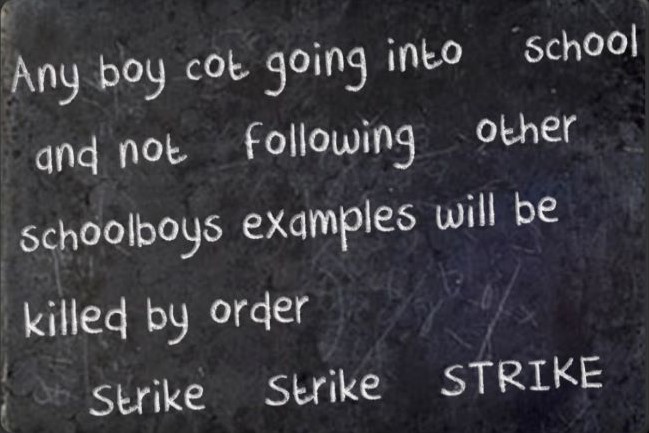

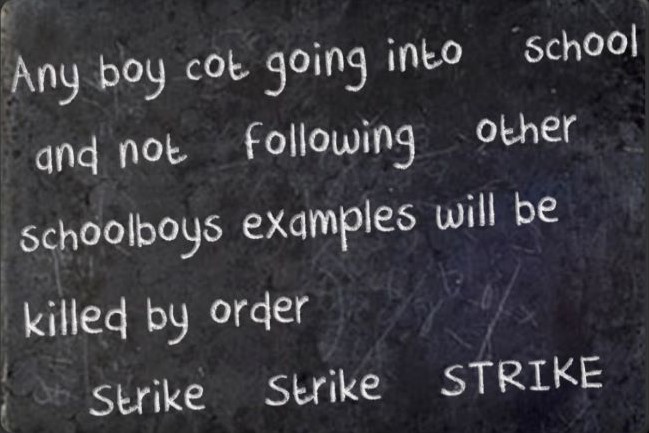

Arriving at the school on the 13th September 1911, one of the teachers was surprised to see a note chalked on the door

“I.T.S.B.U.

Any boy cot going into school & not following other schoolboys examples will be killed by order.

Strike Strike Strike”

The initials stood for Irish Transport & School Boys Union, and in an area where Jim Larkin’s Union was achieving great success, and where a rail strike had just broke out at North Wall (eventually spreading nationwide), it is not too hard to figure out where they boys got their ideas for their strike from. These newspaper excerpts give a flavour of what occurred:

“A large number of the boys assembled in the vicinity of the schools about 9.30 a.m. and paraded the district, carrying flags in which were shown their demands. The strikers sent out “scouts” in all directions to prevent any pupils entering the schools. The police arrived on the scene and were busily engaged watching the boys, who kept parading for a considerable time.”

“On Wednesday morning some boys who attend the East Wall National Schools, Dublin followed the example set by pupils in several schools in England, and went “on strike.” At nine o’clock they assembled on the East Wall Road and refused to allow other boys to go to school. Their demands for cheaper books and shorter hours were boldly chalked on flags which they carried. For some time they marched about cheering and shouting and amusing themselves with such mischievousness as throwing cabbage stumps at doors.”

A reporter from the Telegraph turned up on the second day and interviewed some of the boys. They were articulate, well able to express their grievances while also providing classic howlers such as this:

“…put down that, and say that if we don’t get our rights we won’t go back. We will bring our all the boys again tomorrow and nail the boys who are at school this evening. We’ll give every one of them two or three black eyes.”

The strike lasted for only three days with approximately half the pupils on the roll books not present. The alleged ring leaders were soundly punished, as vividly noted by Homan:

“After rigorous inquiry I selected three of the worst and biggest – two pupils and one ex-pupil. I took down a drill-staff from the rack, got a tough cane from a neighbour, sent for the heroes’ parents’, calmly recited their exploits, placed staff and cane at the parents’ disposal. The whacks, the howls, the lashes, the screams, the smashing of the staff, the weals of the cane, the angry shouts of the parents, the piteous cries for mercy, produced an impression on the upturned, hushed, pale faces of the hundred and fifty boys to whom punishment in school was so new. At a signal from me the execution stopped”.

While newspaper reports treated the whole thing as a joke, the school inspectors investigated the events and examined the boys’ demands. While no public acknowledgement was made regarding any complaints, some of the issues raised were highlighted in reports and a spotlight was thrown on the running of the school. The conduct of J.F. Homan was raised in the investigation and his competency questioned.

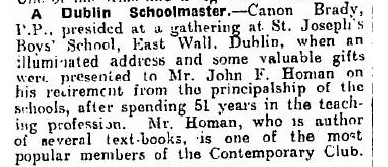

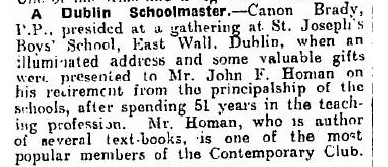

JF Homan retirement July 1926

“School Days over”

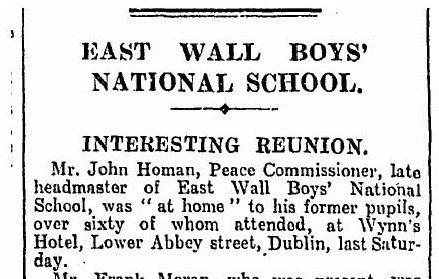

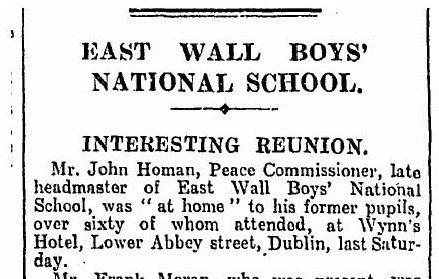

J.F Homan may have been a controversial figure and at times, his judgement was somewhat questionable, but he was also popular with many of his pupils. He retired at the end of school term in 1926 and a farewell event was held in the school which was presided over by Canon Brady, school manager and Parish Priest of St. Laurence O’Toole’s Parish. The following year he attended a school reunion at Wynns Hotel where he was joined by over sixty past pupils.

East Wall Boys School reunion 1927

In 1926, he was appointed a Peace Commissioner and subsequently became heavily involved with the Central Branch of Cumann na nGaedheal .

At their AGM in 1929 he:

“Congratulated the central branch of the Association on the wonderful progress that it had made in two years, and that they could look forward to a better future of usefulness and patriotic endeavour. Thank God the dangers of the past years had passed, and amongst those who helped the country in those years were members now of their central branch. The central branch was the beginning of a new movement: a movement towards cohesion and towards getting the scattered units to stand side by side as one. It was the great object of the central branch to put an end to all division in this country. They must hammer out their own regime and their own system, and the first step towards establishing a real and proper political system in Ireland was to achieve the unity that they all desired.”

J.F. Homan passed away in the 1940′s aged 84 years.

His was an extraordinary life.

JF HOMAN listed in Ambulance Brigade Roll 1916

For further information, corrections and clarifications:

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

This valuable historical document is courtesy :

South Dublin Libraries

Dublin Diocesan Archives

(with appreciation to David Power , Library Assistant)

The full transcript of JF Homan’s “Memorandum of Ambulance work and efforts for peace” can be read here :