Jul 23

Fairview’s Trees – a part of local and National history

The Irish Forestry Society had been founded in 1902 in the wake of a privately commissioned report in the 1880s which suggested that the proper reforestation of Ireland would not only have important health benefits for the country but would potentially create a substantial amount of employment. As the then government failed to act in the intervening years the Irish Forestry Society was born and decided to take matters in hand through demonstrations at annual events such as the RDS Spring Show and Cork Exhibition as well as organizing trips to forested estates of native Irish Trees. Former Lord Mayor and MP, Charles Dawson, stated that not only would the trees being planted at Fairview assist in the battle against the “scourge of consumption”, but he noted that many of those involved in the ceremony “worship at different alters” yet it showed that it was “in the power of all creeds and classes to join together and do something for their common country.”

Jun 12

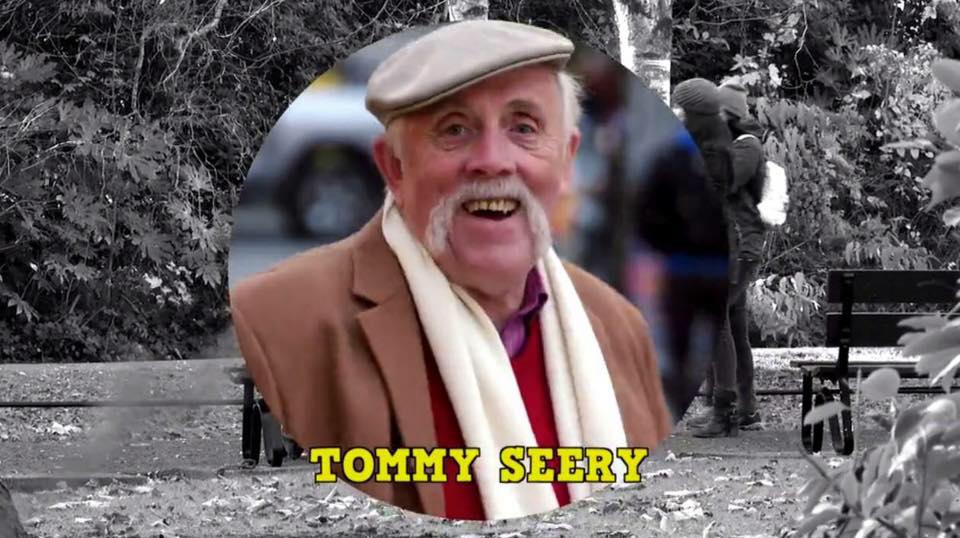

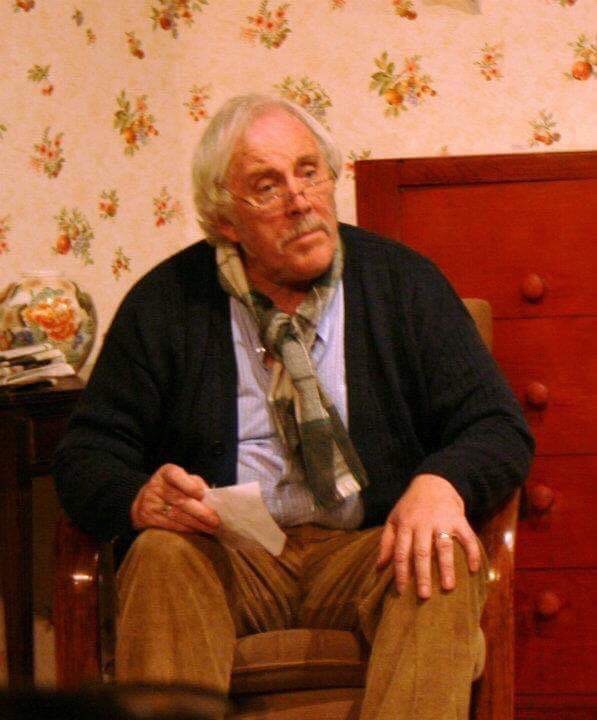

Tommy Seery : A tribute

It was with deep sadness that we all learned of the passing of our friend Tommy Seery on Saturday last , 10th June 2017 . A true gentleman , and surely one of East Walls finest . This tribute was written by Paul Horan on behalf of the East Wall PEG Drama & Variety Group :

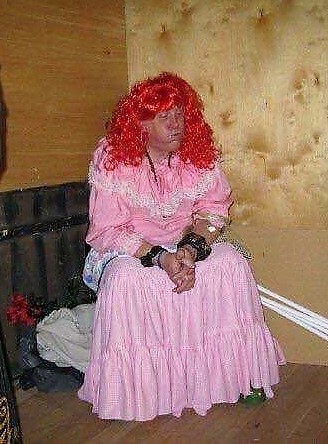

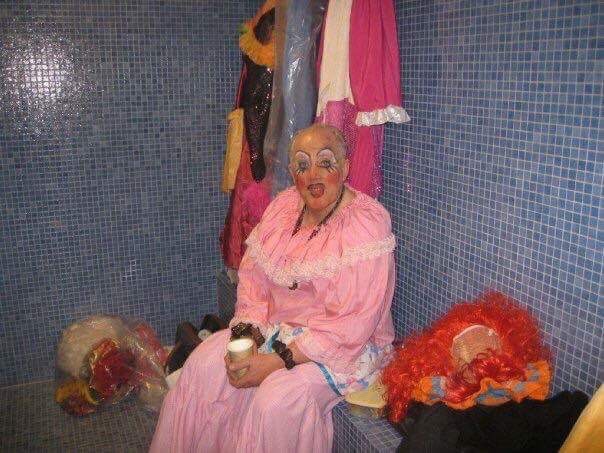

Tommy has been a great stalwart of our group since it’s inception. An immensely talented actor and performer, Tommy’s inordinate talents were constantly in demand on various stages both amateur and professional, however he always found time to return to East Wall PEG to perform in our various projects, perhaps most memorably as Hennessy in “The Risen People”or as the blind Richard Harkin in “The Seafarer. For some however, particularly the younger members of the community, Tommy’s most fondly remembered performances will doubtless be as the Dame in our annual Pantomime.

Those who were fortunate enough to see Tommy on stage can bear testimony to his superior capacity to vividly portray any character, but what they failed to witness and what we as fellow performers continually witnessed over many years, was his constant generosity and encouragement to his peers, particularly younger members of the group. He was a pleasure to know and perform with, and he leaves behind him a void that will not soon be filled.

Our deepest sympathies to his wife Rose and Family.

We leave you with this wonderful clip of Tommy appearing in the RTE television show “Senior Moments” , where his quick wit and unmistakable laugh are very much on show.

We leave you with this wonderful clip of Tommy appearing in the RTE television show “Senior Moments” , where his quick wit and unmistakable laugh are very much on show.

May 24

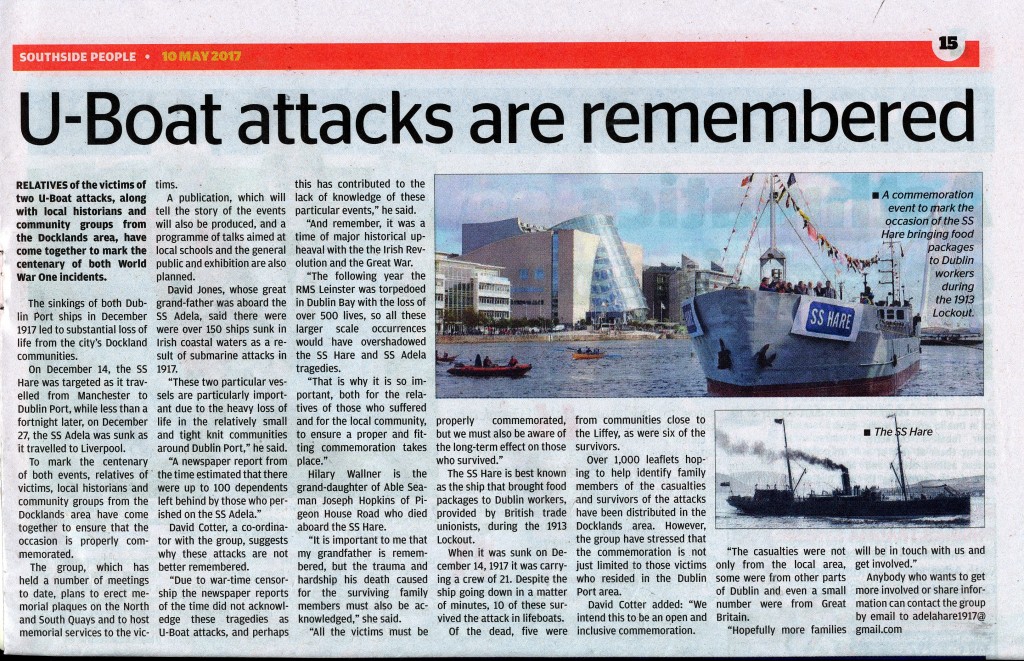

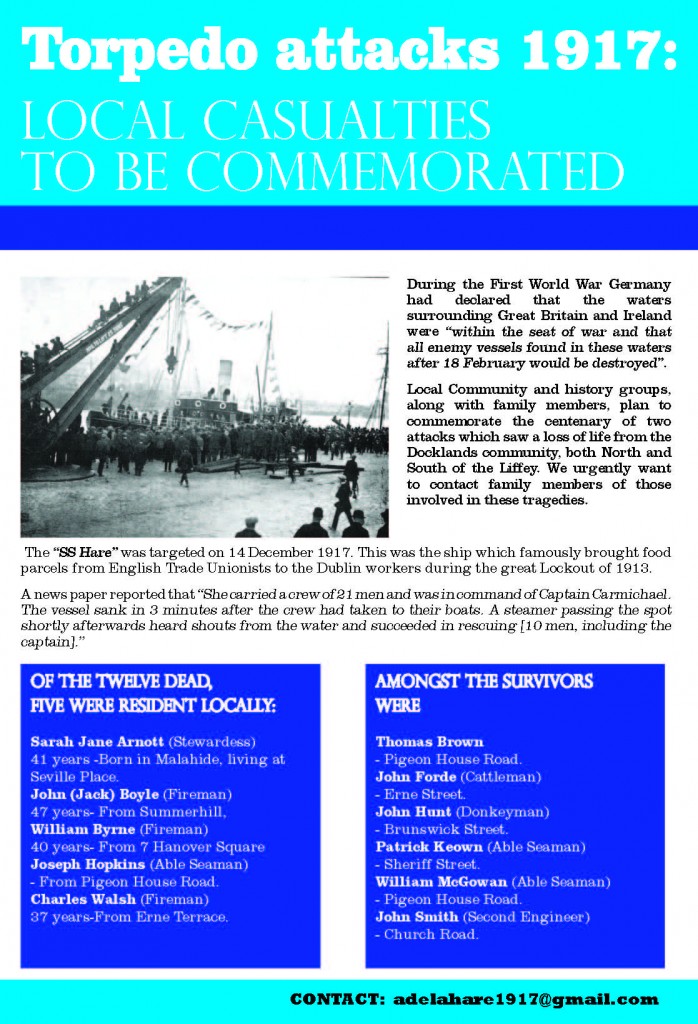

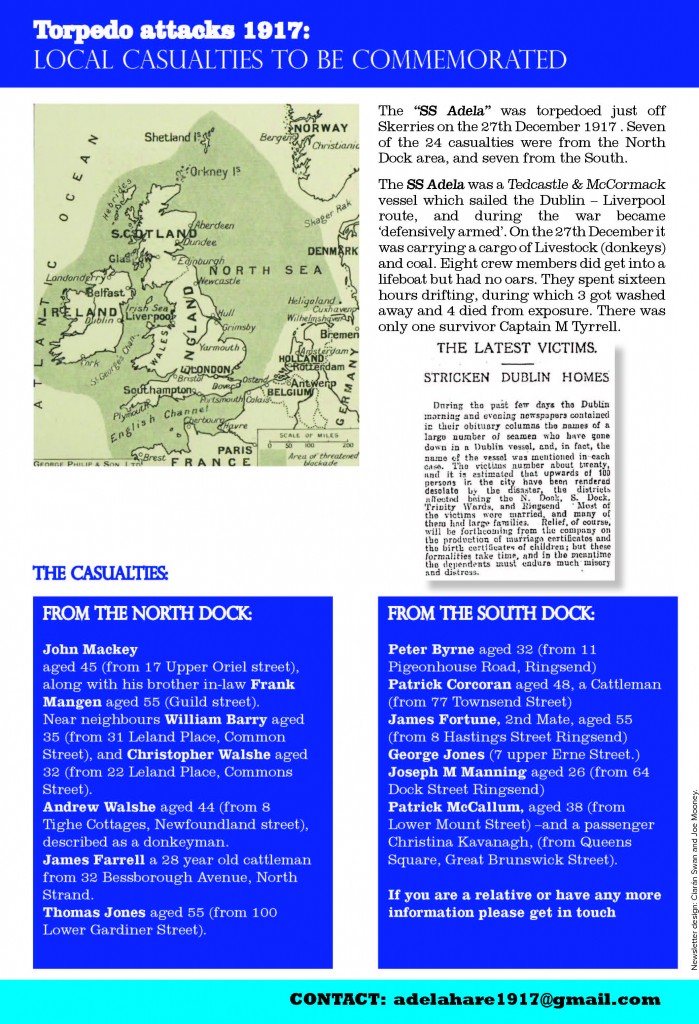

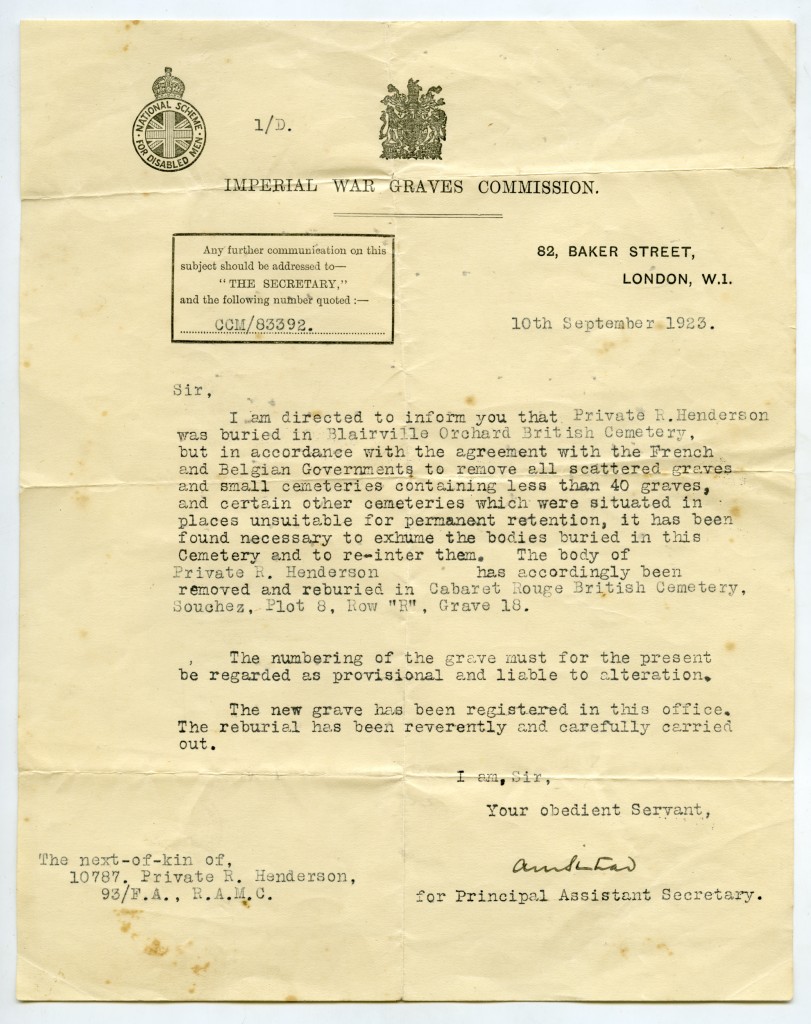

1917 Submarine victims – Media coverage of appeal for family contacts

This year will mark the centenary of two u-boat attacks on Dublin Port ships, which led to a substantial loss of life from the Dublin Dockland communities. On 14th December 1917 the SS Hare was targeted as it travelled from Manchester to Dublin Port, while less than a fortnight later, on the 27th December the SS Adela was sunk as it travelled to Liverpool.

As we approach the centenary of these events, a group of relatives of attack victims along with local historians and community groups from the Docklands area have come together to ensure that the occasion is properly commemorated. An appeal for family members of the victims of both attacks was issued which has some success so far . See very comprehensive coverage in The Southside People newspaper , and link below to excellent interview on NEAR FM with local historian David Cotter and Hilary Wallner , grand-daughter of one of the SS Hare casualties. Sets out very well why the whole commemoration programme is so important.

http://nearfm.ie/podcast/?p=21942

Further media coverage included an interview with Joe Duffy on the special Easter Monday Liveline , broadcast from the Custom House , and an upcoming feature in Newsfour community paper . If you are interested in getting involved or can help us contact family members please get in touch

adelahare1917@gmail.com

May 13

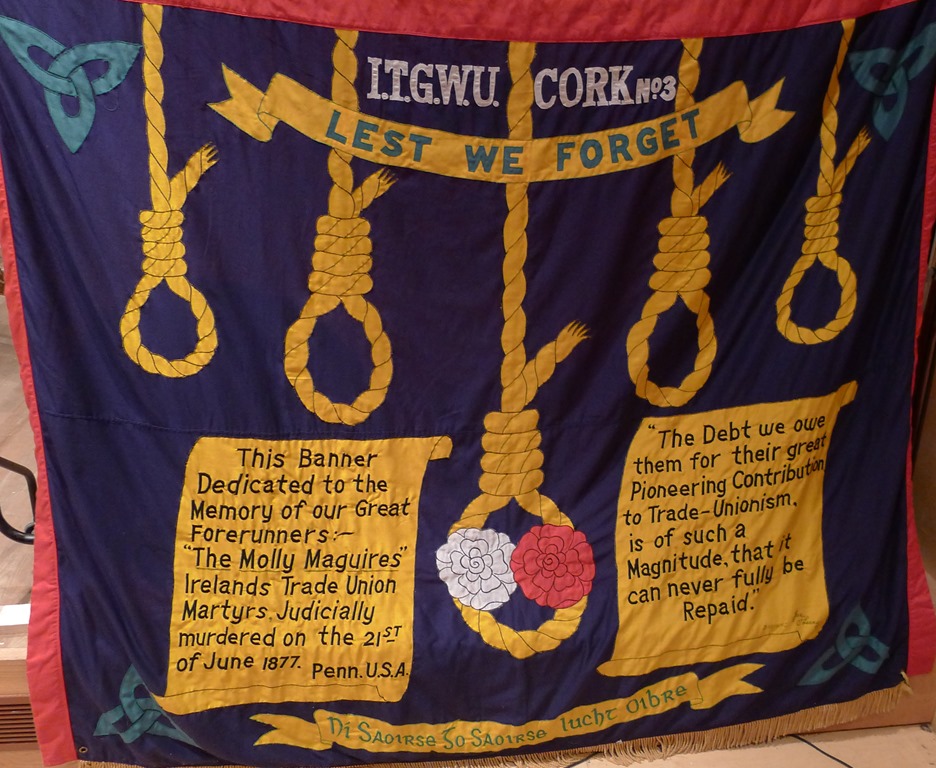

SONGS of the Molly Maguires:

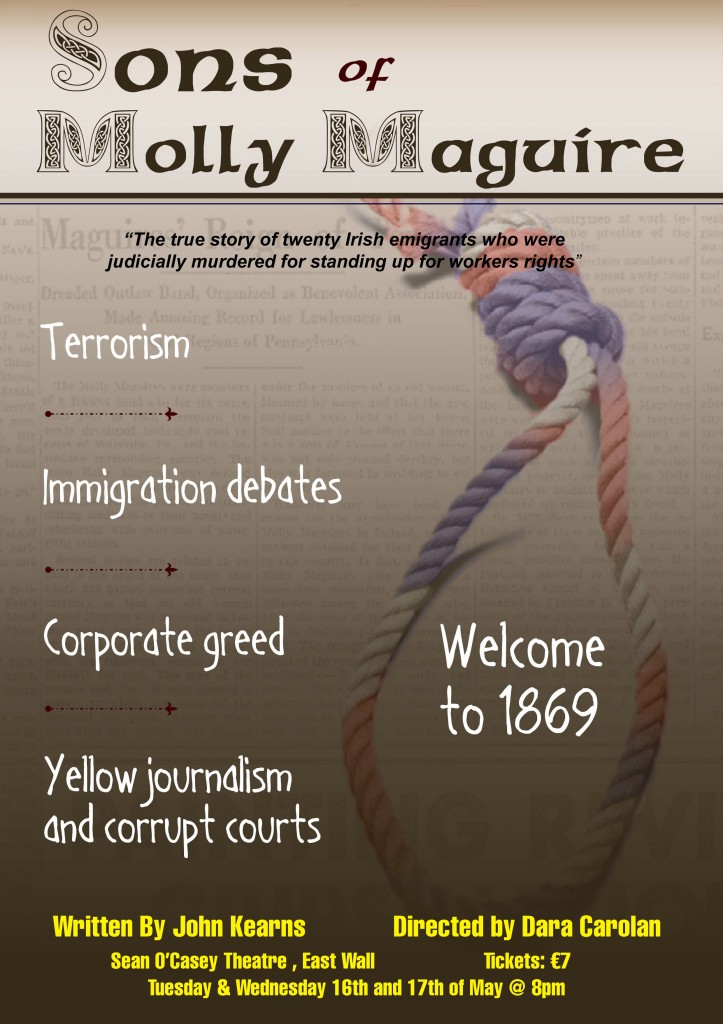

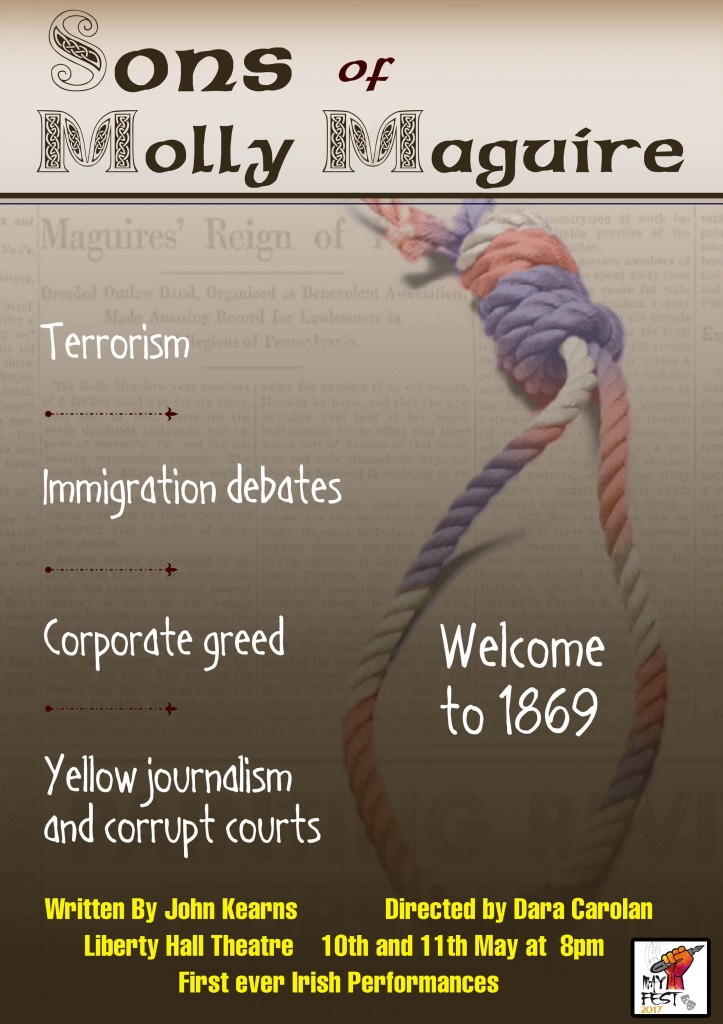

Last year saw the Irish premiere of John Kearns play “Sons of Molly Maguire” at Liberty Hall Theatre, as part of Mayfest 2017. It was very well received , as were the two additional performances which were added , Tuesday 16th May and Wednesday 17th May at the Sean O’Casey Theatre , East Wall .

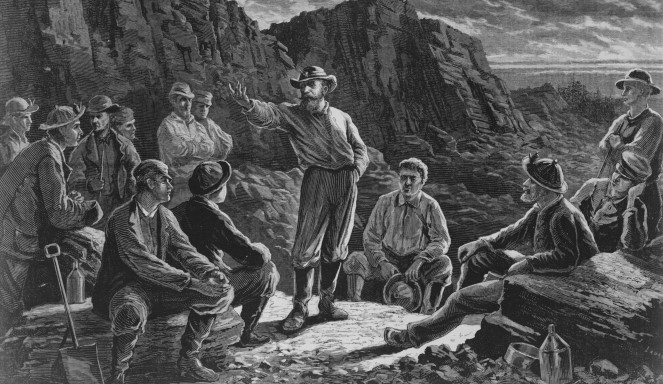

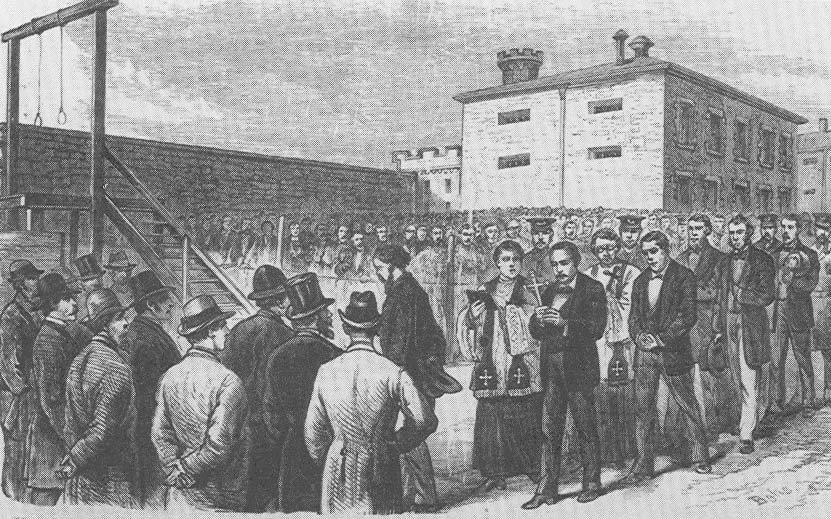

This year marks the 140th anniversary of the execution of ten Irish emigrants in 1877, accused of acts of violence against mine owners, foremen etc, in the Pennsylvania coal fields. Remembered as “Day of the Rope”, a further ten men would also be hanged over the next two years, mainly based on evidence from a fellow Irishman who infiltrated their community on behalf of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Having previously played at the Midtown International Theatre Festival in New York, where it was nominated for five awards, these performances of “Sons of Molly Maguire” represented the first time this story had ever been told on an Irish stage.

As we look forward to these not-to-missed performances , we thought we’d take some time to look at some popular (and not so popular) SONGS of the Molly Maguires . We start of with the most obvious one . For many people, their knowledge of the Molly Maguires extends to the song by the Dubliners, recorded in the late 1960’s.

A popular and rousing sing-along , the song sheds little light onto the story of the Mollies , though it does reassure us that while they have their faults they do have one important saving grace - “They’re drinkers, they’re liars but they’re men” and also gives us plenty of warning that we’ll “ never see the likes of them again” .

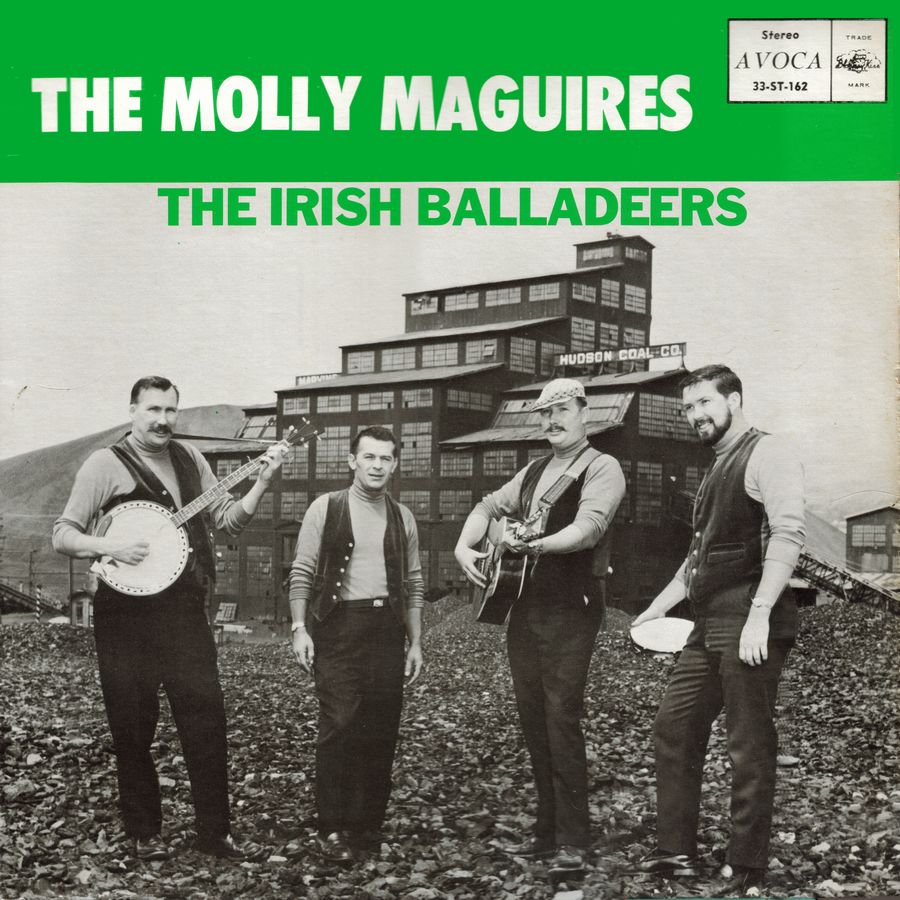

Far more interesting in terms of historical relevance are these two songs recorded by the Irish Balladeers, and appearing on their 1968 album simply titled “The Molly Maguires”.

“If you stand in the dark with your ear to the wind

you can hear the Sons of Molly.

Down in the dark of the old mine shaft

you can smell the smoke and the fire.

And the whispers low in the mines below

are the ghost of Molly Maguire.”

This next one has a very light-hearted jaunty sound, released by the Irish Rovers in 1971. This Irish / Canadian band are probably best remembered for the incredibly stupid song “The Unicorn”, but also released a version of the even more stupid “Snoopy vs the Red Baron”. Their “Lament for the Molly Maguires” actually has a decent bit of the history in there (more than the Dubliners one), but probably stands out most for being the only song here which explicitly refers to the questionable claim that “Many’s a Welshman lost his ears”.

In 1970 Sean Connery and Richard Harris starred in “The Molly Maguires”, which is the other common reference point for people when they’re mentioned. The score by Henry Mancini is very well considered, and if you’ve got 14 minutes to spare here’s a selection from it.

MOLLY MAGUIRES…on stage at Liberty Hall

MOLLY MAGUIRES…on stage at Liberty Hall

May 06

“No one dares to push them around” – The story of The Molly Maguires

It is remembered as “The Day of the Rope”, when, on the 21st June 1877; ten Irishmen were hanged in Pennsylvania. By the end of 1879 a total of twenty Irish Immigrants had been executed for their alleged role in the deaths of mine owners, foremen and police in the Pennsylvania coal fields. And last year ,for the very first time, their story was told on an Irish stage. As part of MayFest 2017 at Dublin’s Liberty Hall Theatre, “Sons of Molly Maguire” by John Kearns received its Irish premiere on 10th and 11th May.

John Kearns is the Treasurer and Salon Producer for Irish American Writers and Artists (IAW&A). He is the author of the short-story collection, Dreams and Dull Realities and the novel, “The World”, along with plays including “In the Wilderness” and In a Bucket of Blood. “Sons of Molly Maguire” has previously been performed at the Midtown International Theatre Festival in New York, and this is the first production outside of the United States.

While telling a fictionalised version of the Molly Maguires’ story, the play blends realism with pageant, mime and flights of poetry. It also questions the construction of history itself, since the illiterate alleged Mollies left no records preserving their point of view. In this short feature, Joe Mooney of the East Wall History Group explains the historical background to their story.

“Thousands are sailing…”

In the mid to late 1800s thousands of Irish immigrants arrived in America. They had left their homeland to escape famine, land seizures, poverty, religious and political oppression. For many, the dream of a new life in the land of the free was soon to end as they found themselves facing old oppressions in a new guise. Those who settled in the mine fields of Pennsylvania had carried more than dreams across the Atlantic; they also brought the traditions and tactics that had flourished at home. A merging of agrarian revolt and developing proletarian organisation gave birth to the militancy associated with the Molly Maguires.

The Pennsylvania coal-fields were booming as Irish Immigrants arrived. Conditions for all workers were appalling, and competition for jobs was fierce, with the companies using immigrant labour to force down wages. The mining bosses often owned the housing the workers lived in and food and other essentials were sourced from the overpriced company store. Children as young as seven were employed. Long hours, a rush to meet quotas, and unsafe conditions led to fatalities and disasters. In Schuylkill County, home to thousands of the Irish, 566 deaths and over a thousand and a half serious injuries were recorded in a seven year period. In one fire 110 miners died as there was no secondary exit available to them. Safety laws did exist, but as the coal companies themselves were responsible for enforcement these were ignored.

Organise!

In 1868 a miners union, the Workingmens Benevolent Association (WBA) was established to fight for improved pay and conditions. Its Irish born founder John Siney had previous trade union experience in Lancashire. Most of the Irish miners became members of the WBA and were well represented in its leadership.

The WBA was not the only group they joined. Aside from Labour concerns, the Irish again faced racism and religious discrimination. Being rural, Catholic and Gaelic speaking they stood out amongst other immigrant communities. Many had gravitated towards the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), to enjoy the associated fraternal benefits.

And then, of course, there were the Molly Maguires.The Irish in Pennsylvania had come mainly from north western counties, particularly Donegal, associated with agrarian secret societies and land war violence. The tactics of groups such as the Molly Maguires, Ribbonmen and Whiteboys —intimidation, threats, assaults and assassinations —that had targeted landlords, land agents and bailiffs at home were just as effective against mine owners, foremen and the police. New enemy, new battlefield, same response. The origin of the name is uncertain – it had been used previously in Eire, and legend says Molly Maguire was the victim of an early eviction who had sought retribution. The expression “Take that from a Son of Molly” was supposedly shouted before a killing in revenge attacks.

The Coal, Iron and Rail baron

Just as William Martin Murphy is synonymous with the 1913 Lockout in Dublin, one name stands out amongst the capitalists of Pennsylvania – Franklin B.Gowen. He was no friend of the workers, and was determined to smash their organisations – when locomotive engineers had asked for a pay rise he demanded that they leave the union or give up their jobs. During the great railway strike in 1877, he thought himself immune, and bragged that “the men have no organisation, and there is too much race jealousy existing among them to permit them to form one.” They did in fact strike, and ten unarmed people were shot dead by the state militia. He also had many political connections, and a private force, the ‘Coal and Iron Police.’

In 1874 he initiated the Anthracite Board of Trade, an employers’ federation, and instigated a strike by imposing a 20% pay cut. The ‘Long strike’, ended in defeat as workers were starved into submission. Jailings, vigilante attacks and murders took place at this time.

“…print the legend”

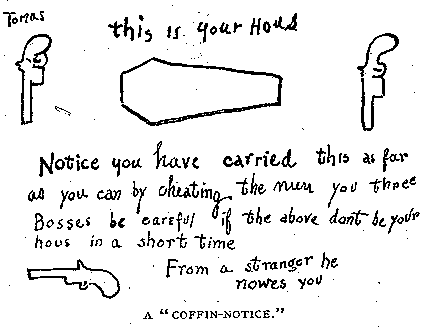

Court cases attributed 16 deaths to the Molly Maguires. The first was a mine foreman beaten to death in 1862, the last a foreman, shot dead in 1895. Other acts associated with the ‘Mollies’ were sabotage, arson, assaults and intimidation. ‘Coffin notices’ – threats with pictures of coffins (or pistols) were posted against enemies, some signed M.M. Many of the actions were carried out by men with painted faces and wearing long dresses, not only as disguise but a theatrical flourish in imitation of their Irish forefathers. This suggests cultural awareness as well as economic necessity in their actions.

Gowen was determined to smash all threats to his empire, and targeted with equal venom the legal WBA and the outlaw Mollie Maguires. He unleashed a wave of violence using his private police force and vigilantes, and employed the notorious Pinkerton Detective agency to infiltrate the Irish workers. Even amongst his own class some concerns arose about his approach, buthe was a canny propagandist, and he used the newspapers to justify his actions. Soon the press was full of terrifying tales of the savagery in the coalfields, and the WBA, the AOH and the ‘Mollies’ were branded as all part of the same foul Irish conspiracy. These were often accompanied by illustrations depicting the miners as ignorant and often ape-like, familiar racist propaganda. Anti-Catholic prejudice was also invoked, even though the Church of Rome threatened excommunication for belonging to a secret society.

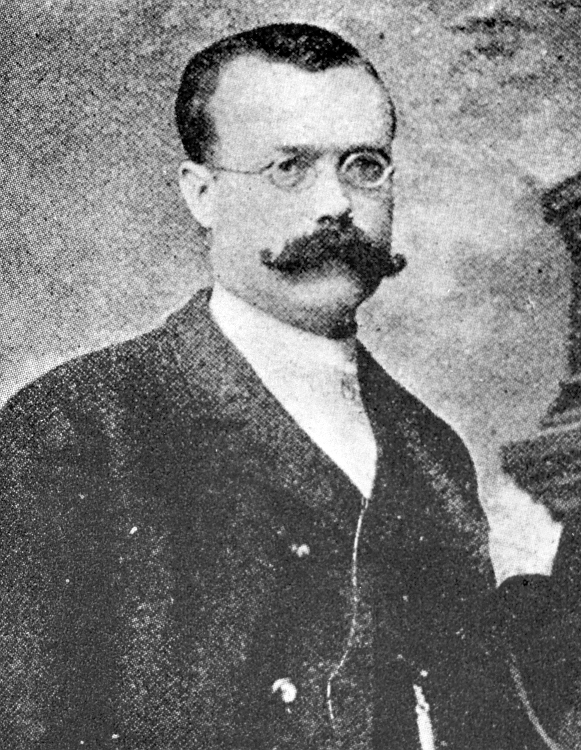

Infiltration and executions

Gowen’s most successful step was the employing of Pinkerton detective James McParland. Using the alias James McKenna, he utilised his county Armagh birthplace to integrate himself into the Irish Community. The majority of the Irish were illiterate and poorly educated, and the fact that McParland/McKenna could read and write gained him access into the local organisations.He became secretary of the local AOH and close to the militants. It later emerged that his two brothers were also involved in this infiltration.His investigation and testimony would lead directly to the trial and execution of twenty alleged ‘Mollies’. During his years of subterfuge, information provided by McParland was used by company vigilantes to identify targets for murder. McParland had no scruples about this, but had a crisis of conscience when the wife of an alleged Molly Maguire was shot dead. In a letter of resignation (soon to be withdrawn) he asked “What had a woman to do with the case—did the ‘Molly Maguires’ in their worst time shoot down women?” and added that “I will no longer interfere as I see that one is the same as the other and I am not going to be an accessory to the murder of women and children. I am sure the ‘Molly Maguires’ will not spare the women so long as the Vigilante has shown an example.”

His conscience didn’t trouble him for too long. His actions would lead to the deaths of twenty alleged men ,including John Kehoe (also known as ‘Black Jack’), branded as ‘King of the Mollies’. Aside from McParland’s testimony, paid informers and pardoned criminals provided the ‘evidence’, and Gowen himself had been appointed special prosecutor.

Many of those executed proclaimed their innocence until the end. Alexander Campbell slapped a muddy handprint on the wall of his cell and promised that “It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man”, and can still be seen today. A century after his death, John Kehoe received a posthumous pardon from the Pennsylvania governor Milton Shapp in 1979.

Failure follows success

It is possible that some of those hanged were involved in militant activity, but it was for the ‘crime’ of self organisation that they were really ‘guilty’. Gowen later promoted a similar conspiracy relating to the Knights of Labor but was unsuccessful. He died from a gunshot wound to the head in 1889. It would be wishful thinking to accept the theory that this was an act of Molly vengeance; it seems most probable that he committed suicide.

McParland also continued his crusade to undermine the growing trade union movement in the rail and mine industries,including attempts in Kansas, Colorado and Idaho. He took on the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Despite placing an agent on the unions legal team,he failed spectacularly in a trial aimed at securing the execution of the WFM leaders. All were acquitted, including Big Bill Haywood. McParland was now notorious, and one labour leader characterised him thus: “He will do anything, no matter how low or vile, to accomplish his purpose”. He died in 1919 of natural causes.

Myth versus truth

The full truth of the Molly Maguires is probably lost to history. The fact that the Irish men involved were mostly illiterate, (and in a secret society), means that they left no accounts of their own. Sensationalist journalism, propaganda, detective reports, trial testimonies and popular ‘histories’ published by the Pinkerton Agency all exist , but tell the story from the other side.

Some believe that the ‘Mollies’ were a fiction, playing on anti Irish/Catholic bigotry to justify the smashing of the WBA and A.O.H, two lawful organisations. There are good reasons to believe this – any union was anathema to a robber baron, and Jack Kehoe , a community leader, intelligent, and willing to throw his hat into the political arena, could have very easily created a power block among the Irish miners.

However while the ‘Molly’ threat was undoubtedly exaggerated and manipulated by Gowen and McParland, it is not credible to state that no such organisation existed. Whether as an oath bound secret society or a loose association of militants, linked or not with other organisations, there is no doubt that they existed in some form and engaged in violent action. Creating the impression of an ever present and all powerful movement would have been an appropriate tactic to adopt.Given the circumstances of the time and district, it is clear that those involved in ‘Molly’actions would also be members of both the AOH and WBA, which does not mean that all were part of one unified grouping.

Martyrs to the cause of Labour

The Irish immigrants were thrown in at the deep end of the industrial revolution, part of the new proletariat and combatants in a bitter class war. They responded in a manner consistent with their own traditions and history of struggle.

No matter which way we interpret events or judge those involved, we must remember that twenty men were hanged. They were casualties in a class war and are rightly recognised as working class martyrs both in Ireland and America.When Kehoe received his pardon in 1979, Governor Shapp said all Pennsylvanians should pay tribute to “these martyred men of labor.”

“Sons of Molly Maguire” , written by John Kearns and directed by Dara Carolan received it’s Irish premiere as part of Mayfest 2017 at the Liberty Hall Theatre on Wednesday & Thursday 10th and 11th May @ 8pm .

Two additional performances also took place at the Sean O’Casey Theatre , East Wall on Tuesday & Wednesday 16th and 17th of May @ 8pm .

May 01

“Ladies & Rogues” – Sean O’Casey Theatre , May 2017

The Collective Theatre Company presents :

“LADIES AND ROGUES”

A spitfire comedy based in 19th century London.

Five Aristocrats are trapped within the opulent Rochester mansion…. amidst societal revolution.

They can surive the night, if they put down the sherry & their ignorance of the world around them.

The five actors playing them, are on the cusp of their greatest performance of their lives.

They can surive the budget constraints and preview night ….if they put aside their egos and their incessant need to sabotage each other.

SEE FACEBOOK EVENT PAGE HERE:

https://www.facebook.com/events/1274468802642804/permalink/1274480392641645/

Apr 14

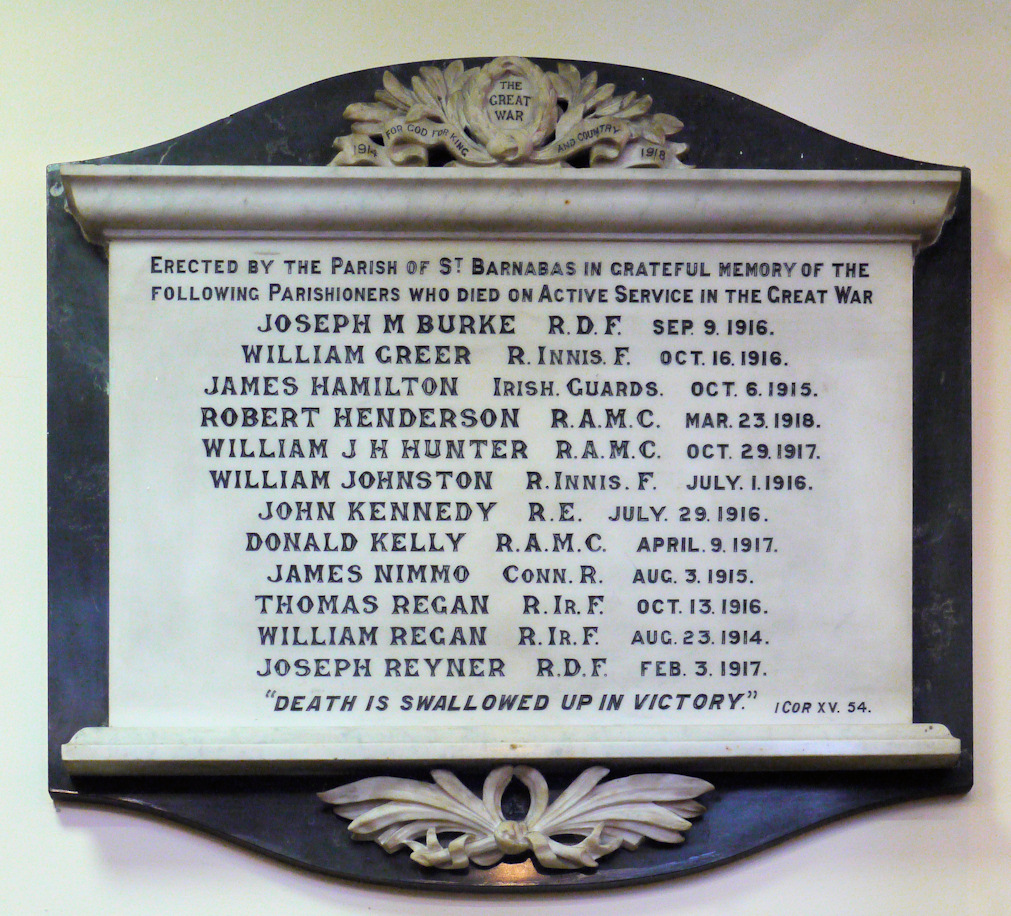

1917 – James O’Neill, The Irish Citizen Army, and reorganization in the Docklands.

It is a Dublin Tradition that crowds gather for the midnight bells at Christ Church Cathedral to ring in the New Year. As the historic year of 1916 was passing into 1917 why should things be any different? Earlier in the week British Army Recruitment posters had been ripped from the railings and the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) had cancelled the gathering at the bells in expectation of trouble erupting. Many of the capitals citizens chose to ignore the ban. By 11.30 a huge crowd had gathered and the small group of DMP on duty had sent for reinforcements. Then at 11.50 two men stepped out of the crowd. A huge cheer went up as their Irish Citizen Army (ICA) uniforms were instantly recognized. The DMP promptly entered into negotiations with the men who soon took off in the direction of Cork Street. The crowd meanwhile shouted, “Up the Rebels!” and started singing republican songs. The incident lasted less than 5 minutes but its effect would be lasting. The ICA had sent a simple message to their fellow citizens – “The boys are back in town”.

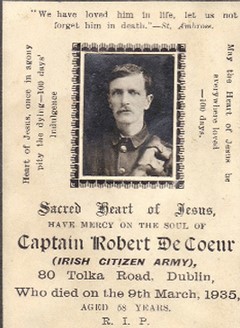

In the first of a series of articles on the events of 1917, we look at the activities of the Irish Citizen Army and its members throughout that year. North Dock locals such as Willy Halpin , Tom Leahy , Christine Caffrey and Daniel Courtney ( all Easter Rising veterens) would continue their revolutionary actions. As the ICA went through a period of reorganizing, among the most significant figures to emerge would be James O’Neill and Robert ‘Bob’ DeCoeur , both who had moved into the area .

“for the big day which was surely coming.”

On 24th December 1916 over 300 prisoners, arrested in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, had arrived back at the North Wall just in time for Christmas. Among them was Alfred George Norgrove who his way home to Strandville Avenue marveled at the rich fruit pudding which had accompanied him on the boat over. In recent weeks, hams, cakes, and other Christmas fare had been steadily arriving at Frongoch Prison Camp. Relatives had expected the men to be interned for the festive season had organized a benefit concert at Liberty Hall and purchased the luxury items to make Christmas passable for them. Alfred George’s wife had headed up the pudding making committee and upon his unexpected return the Norgrove’s decided to share their good fortune, bringing their pudding down to Liberty Hall to share with less fortunate comrades in arms.

Despite the best efforts of HMS Helga and British artillery the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU) headquarters on Eden Quay was still structurally sound, although there were a number of large gaping holes in its outer walls and much of the plaster had been shot off the internal ones. Part of the front steps had been destroyed by a hand-grenade and some of the railings were missing but the room used for concerts and plays was virtually untouched. Many others had a similar idea to Alfred George, and the Citizen Army women had decked out the building in festive fare. For the newly returned Christy Poole, Liberty Hall was the obvious destination, and after briefly visiting his family, he headed straight for the building to see what was happening. Having been second in Command at the Stephen’s Green garrison, Poole was the most senior surviving ICA officer and for most of those re-grouping at the Hall he was considered the natural choice to rebuild the army around.

Within days Poole had reconvened the remnants of the Army Council, but it was soon obvious that the ITGWU under Tom Foran and Bill O’Brien was vastly different to its predecessor under Larkin and Connolly and relations would be different. While the union had offered concessions over non-paid dues to those imprisoned during the Rising, they had made a similar offer to the thousands of their members who were still fighting with the British Army in WW1. At the union’s AGM, at which Bill O’Brien was put forward as General Treasurer, Poole and John Hanratty orchestrated bitter opposition which would spill over into acrimonious correspondence in the newspapers, drawing in among others, Sean O’Casey. In their minutes the Union would record the incidents as a disgrace.

O’Brien had been briefly interned at Frongoch in 1916 and had orchestrated a hugely successful strike at the prison camp, which was led by ICA men. However, he was suspected by many of the rank and file trade union members of being too political and seeking to use the strength and finances of the union to advance the fledgling Labour Party rather than advancing workers rights. Many felt let down by General President Tom Foran whom persistent rumors claimed had gone to the Fairyhouse Races instead of fighting at Stephens Green. Christy Poole even claimed he was left holding onto Foran’s rifle in the College of Surgeons waiting for him to turn up. However, in April of 1916 James Connolly had had enough foresight to realize that the Union needed to continue whatever happened during the insurrection, and had asked many key people not to participate for that very reason. Under the leadership of Foran and O’Brien, the ITGWU were about to embark on a plan which would vastly expand the union membership and power by recruiting the vast number of agricultural workers in the country. O’Brien knew that the Citizen Army had an important role to play if they could be controlled. As tensions reached boiling point it was obvious that someone would have to give way and the Trade Union seemed to be holding all the cards.

Into this stand-off stepped James O’Neill, a carpenter and small time building contractor from Leixlip who had acted as the ICA’s Quarter-Master General and Engineer at the GPO in 1916. O’Neill had thought to return to his building business but a series of meetings with Bill O’Brien convinced him to go forward as Commandant of the ICA. The ITGWU allowed him to jump ahead of other contractors tendering for the repairs to Liberty Hall, effectively facilitating an ICA full-time Active Service Unit among his workforce of 1916 veterans to use the Hall as their HQ (and training centre under the guise of a ‘Swedish Exercise’ Club). In between rebuilding the hall, they would be available to intervene in labour disputes, rearm and reorganize. And very soon, following agreements between Bill O’Brien and Arthur Griffiths, they were also engaged in supporting Sinn Fein election campaigns. Much of the year was spent on rebuilding the hall. Other ICA figures such as Alfred George Norgrove, Margaret Skinnider, and David O’Leary were found administrative work in the union while Mick Nolan of the Baldoyle Company became a regional organizer of agricultural workers. Significantly, before the Rising, James O’Neill had moved to 20 Abercorn Road in the heart of the Docklands which put him in a prime position to oversee the renewal of activities in a key area.

In April 1917 O’Neill and Dick McCormick met with Michael Collins and Cathal Brugha of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to look at a way forward for the movement. Elements of the ICA constitution were a real stumbling block but O’Neill and Collins came to an understanding. Brugha was more circumspect, and while he could probably value the speed and effectiveness with which the ICA could be got operational again, ultimately the Dublin Brigade hierarchy would consistently block most attempts by them to engage in military action. For many rank and file Irish Volunteers, as Oscar Traynor would recall, there was “aloofness” about the ICA with many of their members feeling that they were the true “initiators” of the Rising. The ICA also had a socialist agenda that was far more wide-ranging than that expressed by many within the volunteer movement. Despite this, the high-profile nature of the Citizen Army in 1917 would soon have newspaper editorials commenting that the physical force element of Sinn Fein was now represented by the “remnants of the Citizen Army and the less educated Labour element,” while a reporter at the Joseph McGuinness election at Longford in May noted the infiltration of the Socialist Party and Citizen Army. The Catholic Truth Society conference in October called for a “Socialist Catholicism” in Ireland and claimed that the Citizen Army had assisted the oppressed through the barrel of a mauser having been led by a man who was educated by the International rather than the Catholic Church. Later on, Oscar Traynor (Brigaidier of the Dublin Brigade) would claim that by 1919 the ICA were difficult to deal with despite the agreement. However, in 1917 the haste to get things moving again differences were quickly blurred and a spirit of co-operation papered over the clash of ideologies between the ICA and the Volunteers. O’Neill, while retaining the distinct autonomy of the ICA, had agreed that they would defer to the Volunteers Command on all military operations and ultimately this would come back to haunt him and to some extent be the ICA’s undoing. At the April 1917 meeting it was agreed that Michael Collins would be the ICA’s direct contact, but following the cancellation of a raid on Kingsbridge Station for arms the contact was moved directly to coordinating with the Dublin Brigade.

The ICA already had the long established “Glasgow Route” through which explosives and other military equipment had been brought into Ireland before the Rising. Many of the membership had been jailed with hard labour during the Lockout of 1913, and had shown a willingness to take on the difficult jobs while in detention camps after the Rising. In April 1917, these factors would have contributed to recognition that they provided a fast and effective opportunity to re-arm the IRA to launch a new phase of revolutionary activity. Crucially their influence on the Docklands far outweighed their numbers and as the build-up began to a new military campaign the ICA would take on a crucial and overlooked role. Ultimately the lack of action (within the ICA) would frustrate many and the solution would be for their secretary Robert ‘Bob’ DeCoeur to pass potential recruits on to the Dublin Brigade Companies. As part of the agreement it seems many ICA members were assisted by the Bill O’Brien/Michael Collins controlled Irish National Aid Fund. Helena Molony of the Citizen Army was appointed as National Aid Inspector for the North Inner city. Stephen Hastings, an ICA /ITGWU activist had been smuggled out of the country to Wales in 1913 after assaulting a DMP man at North Wall , and had been conscripted into the British Army there. Hastings was arrested for desertion when he attempted to get back to Dublin in time for the Rising. On his release from Prison in October 1917, like Molony, he joined Irish National Aid, distributing monies to a disproportionally large group of ICA Rising veterans whom he was directly involved in organizing.

James O’Neill had clashed with Michael Collins at Frongoch, when he was of the opinion that Collins was getting above himself and throwing his weight around. On one occasion he had picked the “Big Fellow” up and cast him into a ditch like a sack of potatoes. Far from being annoyed Collins was impressed and it seems to have instigated a relationship based on respect, which Collins would try and honor right up to the time of the Treaty. To the rank and file ICA, and particularly Christy Poole, it was obvious that O’Neill had the diplomatic skills necessary to deal with the new ITGWU hierarchy and he managed to keep the ICA at Liberty Hall despite continued opposition from the management. The very public activities and demonstrations by ICA members around Beresford Place would almost lead to the closure of the hall in May 1917, which was only averted by the prompt intervention by the Lord Mayor at Tom Foran’s request. Christy Poole knew he couldn’t compete with O’Neills diplomatic skills and he withdrew his own name from the impending election of ICA Commandant in favor of O’Neill. However, while O’Neill would officially head up the ICA, it was Christy Poole who would lead the men, being largely responsible for their training and recruitment throughout 1917.

While the Irish Volunteers tended to keep their activities low key the ICA were very public in their endeavors ,which in conjunction with a growing ITGWU membership would lead to the Belfast Newletter claiming they mustered 5000 men at one 1917 event. O’Neill and Poole, tapping into the ICA experience of organizing strikes and mass-meetings during the Lockout of 1913, pulled off a spectacular when an honor guard of 200 men with hurleys accompanied Countess Markievicz from Westland Row Station to Liberty Hall on her release from Prison in England on the 16th June 1917.The DMP had attempted to stop O’Neill and Markievicz sharing a platform there. When a DMP Inspector tried to intimidate O’Neill, he responded “you have three minutes to decide whether you’ll try and keep us off the platform.” The DMP withdrew to a safe distance. The previous week when the DMP attempted to arrest Count Plunkett at a rally in Beresford Place, DMP Inspector John Mills was attacked with a hurley by one of Markievicz’s Fianna Boys and subsequently died.

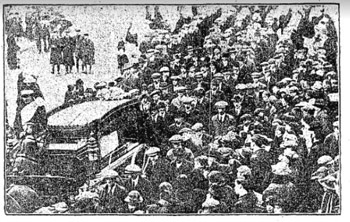

In March Bernard Courtney, son of lockout and Rising veteran Daniel Courteney, died of TB. A huge spectacular funeral was organized with three uniformed companies of ICA leading the procession from St Lawrence O’Toole’s Church to Stephens Green and the College of Surgeons where Bernard had fought, before marching to Glasnevin. The same month at the funeral of GPO veteran Tom “Corky” Walsh in Cork city a large contingent of uniformed ICA including over 600 boy and girl scouts paraded with Volunteers as part of the funeral procession. Similar crowds would participate in the funeral of Stephens Green veteran and Dublin Corporation Councilor William Partridge at Sligo in July. The ICA were also visibly present in force at a number of Volunteer funerals throughout the year.

At Easter, the ICA women caused uproar when Jenny Shanahan, Bridget Davis, and Rosie Hackett, placed a banner recalling “James Connolly Murdered, May 12th 1916” across the front of Liberty Hall in bold black letters. The women had also collected as much of the type used in printing the 1916 Proclamation as they could find and a new edition was printed and distributed as close as possible to the battlefield sites of the previous year.

Arthur Hannon from St Laurence’s Place, North Wall had scaled the GPO, burnt the Union Jack on its roof, and raised a tricolor over its ruins to the astonishment of the Dublin public who gathered below. A second flag was placed at the far end of the building. Tricolors were raised on Nelson’s Pillar, The College of Surgeons, the old Distillery Building beside Boland’s Mill which had been shelled by the Helga in 1916, as well as some ships and boats on the Liffey. These events attracted a crowd, estimated by the DMP, of 20,000 many of whom wore nationalist badges rosettes, and armbands.

Experienced men such as Vincent Poole became involved in managing teams who provided protection, crowd control, and activism during the early Sinn Fein Elections of 1917-18. James O’Neill, John Hanratty, and Christy Poole had all played a significant role in the winning of the Roscommon bye-election by Count Plunkett in January 1917. The ICA would be ever present at subsequent electoral contest over the next 12 months. As both Vincent and Christy Poole travelled the country on election duty they tapped into contacts made during detention in Frongoch, Stafford, and Reading, with Christy organizing drilling and training sessions and occasional lectures to embryonic flying columns in Roscommon, Galway, Clare, and Wexford.The Poole brothers would later act as bodyguards to Eamonn DeValera when he was on the run and hiding in the grounds of the Archbishops Palace in Drumcondra.The ICA Boy scouts had a very visible presence regularly marching in formation and drilling throughout Dublin. On 28thOctober Mattie Connolly and Paddy Duffy from Lower Gloucester Street were arrested leading a group of thirty two scouts through Rathmines following maneuvers at Milltown.

Towards the end of the year, as the city faced into one of the worst winters in half-a-century, many slum landlords, seeing an opportunity of making a killing through compensation from Dublin Corporation, began clearing houses which had been condemned several years previously. In some cases, such as Boyne Street, the entire street faced demolition. William John Larkin of the Dublin Tenants Association set out to stop the clearances and providing back up to his efforts were the ICA. For the Larkinite element of the ICA this was central to what they stood for. Things came to a head on 8th December when Bailiffs attempted to evict tenants from a house in Crabbe’s Lane. The Bailiffs found the rooms barricaded and their attempts to smash in the doors with axes were repelled. The DMP were called and the defenders arrested – John Hanratty, Dick McCormick, and Daniel Courtney from Seville Place all of whom were leading members of the Citizen Army. Courtney had seen this situation before, when almost four years to the day his family were evicted from their home at Merchants Road, East Wall, during the 1913 Lockout. Remarkably the Judge refused to jail anyone and suggested they sort things out amicably.

Shortly before that, following the death of Thomas Ashe on hunger strike, a massive protest was organized at Smithfield with O’Neill sharing the speaker’s platform with Eamonn DeVelera. At Ashe’s funeral the Citizen Army had a significant uniformed presence with many of their members forming the firing party at Glasnevin on the 30th September. 30,000 people passed by Ashe’s body as he lay in state at Dublin’s City Hall and the ICA performed spectacular drilling displays in Beresford Place for half an hour before the funeral. After such a forceful show of strength O’Neill had planned military reprisals in response but this was vetoed by Eamonn DeVelera. O’Neill conceded to Dev’s wishes and whether he realized it or not, this was the beginning of what would be a frustrating period whereby his agreement to abide by and defer to the orders of the Dublin Brigade meant virtually all future operations of a military nature would either be vetoed, cancelled, or taken over by the IRA. As Frank Robbins recalled O’Neill was constantly saying that the ICA must wait “for the big day which was surely coming.”

However, in the spirit of optimism prevalent in 1917 it seemed like anything was possible and the ICA would be, to some extent, at the forefront of it. Jimmy O’Shea pulled off his first coup when he persuaded a British soldier at Portobello Barracks to sell him 17 rifles. Later that year, through a connection with Edward Handley, a Store man at the same barracks, O’Shea would get a regular supply totaling between 50-70 rifles, passed out through the railings at the barracks sports ground at Mount Thomond Avenue. These would be transported by the ICA’s cab men and 1916 veterans Jonathan “Barney” Craven and Dick Corbally to flying columns around the country. Corbally, from Summerhill, had fought at the GPO with his son Larry, a future official with the Marine Port and General Workers Union. In between Cabbying and Carting he worked the cattle boats at the North Wall. Craven from Pool Street, Portobello, had donated his cab for use as barricade during the Rising. Refinanced by Irish National Aid, through a loan endorsed by Collins (which he conveniently forgot to repay), Craven was soon operating practically full time transporting weapons and ammunition across the city or bringing men out on patrols or operations. (Illiterate, Craven eventually lost his profession following his jailing for contempt of court in April 1924 during a case involving his cab. After all his contribution to establishing the new state, deprived of his way of living, Barney Craven starved to death in November 1933. He remains unrecognized for his efforts and no medal was ever issued to his family).

Frank Murray, a Fianna Officer who fought at Boland’s Mill, had been sent to Glasgow in the summer of 1916. Ostensible Murray was to reorganize the Fianna there but by the following March he was appointed head of purchasing for the ICA. Murray had already used the Glasgow route before the Rising and with his socialist credentials was able to move in radical Glasgow Labour circles which had little interest in the nationalism of the Irish Volunteers but strong memories and associations with James Connolly. Scottish sources conservatively estimated that Murray was personally responsible for importing at least one ton of explosives as well as vast amounts of rifles, pistols, and ammunition. 600 detonators, 50 lbs of explosives, and 500 feet of fuse cable would be carried over between April 1917 and the following March along with pistols, ammunition, and other material. He travelled over every two months or so and had rooms in the back parlor of a safe house at 19 Abercorn Road which the ICA acquired in February 1917. (It would be 1919 before he and the property came onto the radar of the British, when it was subject of a number of raids. Despite searches which included ripping up the floorboards nothing was found on the property.

Joining Murray in Glasgow was former ICA woman Christine Caffrey. She had been among a number of women sent by Helena Molony to get work in a munitions factory but had been dissuaded from that type of work at the Glasgow end. Soon she was acting as a courier for Murray, bringing over explosives, ammunition, and pistols. Caffrey’s mother, Elizabeth, lived in Church Street East and her brother Michael was a cattle drover for Michael Cuddy, an extensive cattle exporter from Seville Place. Murray was able to utilise the cattlemen who could provide cover the unloading of arms and munitions from the Glasgow boats as they herded cattle on. Through his Labour connections he acquired pistols from friendly ship’s crews which promptly made their way to James O’Neill in Dublin. The Caffrey house became a regular dump for unloading arms brought in at the North Wall, often stored in the chicken coup in the garden until collected and moved on. In the early stages of 1917 this was usually to Liberty Hall. Caffrey, in the absence of an ICA section in Glasgow, had joined the Ann Devlin Branch of CummannamBan and soon other operatives such as Annie Mooney, and Catherine Rooney, were plying the “Glasgow Route” to O’Neill at Liberty Hall.

Within weeks of returning from Frongoch Tom Leahy was back working in the Dublin Dockyards and assumed the role of Shop Steward of the riveters. Soon he was joined by several former comrades including Citizen Army Treasurer and City Hall veteran, Willie Halpin from Hawthorn Terrace, who became Shop Steward of the Platers in the yard. So many ships were being sunk off the Irish Coast that business at the Dockyard was booming and trained skilled men were in short supply and great demand. Two contracts worth £120,000 had to be turned down, due to an inability to persuade Dublin Port to provide land with which to expand the yard and the shortage of skilled men, so a blind eye was quickly turned at people’s past as the pressure grew to fulfill contracts. Men on the run were found jobs there, jemmy bars for use in raids were being manufactured on the quiet, files were stolen, and component parts for use in weapons or bombs were being manufactured. The Dockyard had a repairs contract with the Royal Navy and each time a ship pulled into dock raids were made on it looking for small arms. As late as the 1930s when tools or parts went missing in the Dockyard people joked “there must be another revolution coming”.

Those who couldn’t be accommodated at the Dockyard were found jobs in the nearby Port and Docks Power Station or the Dublin Docklands War Munitions Factory, which was largely employing women and young apprentices, and manufactured 18 pounder shells for the duration of the war. While the management noted the care and attention of the women towards their work (which they claimed saved the lives of loved ones and neighbors fighting in France) at least two of the girls, sisters from Fairview, made regular withdrawals from the factory of tools and components hidden under their skirts at the end of their shifts.

There were several strikes at the Dockyard in 1917 beginning in February over attempts by Dublin Port to off-load men to the Dublin Dockyard Company without proper pension’s provision or compensation. In October, the yard came to a standstill as Tom Leahy took the riveters out on strike over the non-payment of an increase of 50% on the list price which had been awarded to Clyde Shipbuilding Workers some weeks previously. Dublin Dockyard normally used the Clyde pay-scale and Leahy would represent the men at an arbitration hearing in London which found in their favour. This Dockyard agitation was part of a pattern of activity across the Port area and further afield. In April Grain Carriers had struck for an increase due to the rise in the cost of living, leaving 8000 tons of wheat on the docks. The same week Coal Laborers discharging cargoes for the Alliance and Consumer Gas Company struck, and members of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers working for Dublin Port and Docks came out for a similar increase. In May, the Dockers of the B & I Steampacket Company, and Tedcastle McCormack’s came out as did the Draymen at Boland’s Mill in June. It was a significant development in June when Railway Engineers at Amiens Street, North Wall, Broadstone, and Inchicore all went on strike due to the failure to implement a war bonus which had been awarded in March. Printers, Mill Workers, Laundry workers, bread vanmen, bakers, carters, painters, even hearse drivers, and coffin-makers, all downed tools in the ensuing months. September saw a widespread strike of County Dublin agricultural workers. By October the ITGWU was threatening to bring out over 2000 members leading the Freeman’s Journal to speculate that an all-out Strike was looming. This time, P.T. Daly warned, Clerical Workers would stand with their laboring brothers unlike the past where they could be expected to black-leg. With all of this labour activity going on, it almost went un-noticed that in August Dublin Port and Docks recorded a large consignment of hay bound for British Army horses “spontaneously combusted” in a docklands warehouse. In truth, this was probably one of the first major acts of harassment aimed at the British Army and was probably orchestrated by ICA members working there.

In 1917 Bob DeCoeur moved to 48 Lower Sheriff Street and began working with The Dublin Dockyard Company. Having previously operated the ‘Jacobs branch’ of the ITGWU based at Aungier Street, he had served as a Lieutenant at Stephens Green and his move to the North Docks coincided with him taking on the role of gathering Intelligence within the ICA. Christy Crothers would claim that it was information that he obtained and passed on through DeCoeur which instigated the plan which would ultimately become Bloody Sunday. (Interestingly many of those who would participate in that event, known as the Squad, were local and initially based at 100 Seville Place and many came from the surrounding area). The information gathered was usually passed on via James O’Neill at his regular meetings with Michael Collins, firstly at his new home at Marino Villa on the Malahide Road and later almost weekly at Kirwans Bar at 49 Parnell Street. Although on occasions, such as the important Bloody Sunday information, DeCoeur took it directly to Frank Henderson’s house at Windsor Villas. The move to the Malahide Road was to provide a secluded base for a Collins inspired harassment campaign where the ICA stole DMP and later Army Bicycles which were reconditioned and then “disposed of” in Jimmy Dwyer’s Irish National Aid financed Bicycle Shop on Arran Quay. The ICA would also train in the nearby fields on occasions. (The stolen bicycle operation, involving Mick Kelly who moved into a house nearby, would expand into stealing British Army motor cars which would ultimately lead to O’Neill and Dwyer’s undoing for which they were jailed for 9 months during a British sting operation in September 1919).

By that time Bob De Coeur’s information network was so all encompassing that it became near impossible for the British to raid a house near the Docklands without the residents being informed at least 30 minutes before hand. Famously Elizabeth Caffrey loaded her washing with newly arrived pistols having been warned that the Auxiliaries were about to raid her in about ten minutes time. As the lines blurred between Volunteers and Citizen Army, a network of safe houses evolved under O’Neill’s leadership, as the ICA took control of the Docks. Non-aligned dock workers such as Pat “Cocker” Daly, brother of ICA 1916 veteran Tom “Blackguard” Daly, could be relied on to participate in raids to get guns off ships to such an extent that one courier described what amounted to a game of pass the parcel as weapons were handed from one to the other until they arrived at someone who knew where to take them to. Tom Healy, a cattle drover and ICA man, kept an arms-dump at his house at 23 Lower Oriel Street. At one time this included a Lewis Machine Gun , which remained in his living room right up to the ascent of Fianna Fail to power in the 1930s.Huge numbers of families with Dockland connections have their “arms dump” story . Despite a strong British military presence in the area , by the time that Q Company of the Auxiliaries set up head-quarters at the London and North Western Railway Hotel on North Wall the network was so well developed that attacks could be organized right under their nose and even directly on their barracks itself. The Auxies trained spot lights from the rear of the hotel on Sheriff Street and Spencer Dock but operatives going on maneuvers subverted this by crawling on their hands and knees using the wall of the bridge as cover. The Fairview and GPO veteran (and eviction resistor) Daniel Courtney, finding himself heading towards an “Auxie” checkpoint at Guild Street one evening calmly dropped into the “drunken paddy” mode and having amused the Auxiliaries for a sufficient time was sent on his way home to Seville Place with the consignment of pistol he’s just received still safely hidden under his coat.

Ultimately the Volunteers with their greater resources and manpower would catch up. Tom Ennis, an Irish Volunteer working in the Goods Depot at the LNWR kept a close eye on potential military supplies for the British Army coming through the Railway Station. When he was convinced that useful equipment was coming through he quickly organized a raid to remove it. These were mostly successful although on one occasion ‘a crate of revolvers’ turned out to be heavy duty handcuffs to the bemusement of his team. Ennis would command the 2nd Battalion Volunteers during the burning of the Custom House. The 2nd Battalion, drawing on local men from Fairview, North Strand, and the Docklands, would use key workers on the various railways to identify “contraband goods” during the Belfast Boycott and numerous raids were undertaken by D and E Companies to destroy such consignments, usually in the canal between Spencer Dock and Charleville Mall on the North Strand. By 1919 the Dublin Brigade would use their ITGWU membership contacts to set up alternative means of importing arms through Dublin Port through the formation of (their own) Q Company, largely composed of Dockers and quayside workers who could extract material past the Customs House without drawing attention. To some extent this made the ICA’s long established Glasgow operation redundant. (Oscar Traynor would later recall that he felt by 1920 the ICA had ceased to exist as so many of their men had transferred over to the Dublin Brigade in an attempt to see action).

To some extent it is easy to think that the ICA sat out the war but in many ways, because of the deal made in April 1917, their hands were tied. The speed with which they had reformed meant that their ideological philosophy had been blurred and compromised and the thinly welded factions would ultimately come asunder. Their high profile in 1917 must have worried the more secretive Volunteers who were preparing for the next phase of the military campaign against British Rule. It was only after the burning of the Custom House, (in which, by arrangement with Bob DeCoeur, quite a few ICA members took part) that they returned to what could be considered regular military operations. Even then these largely consisted of burning or destroying contraband as part of implementing the Dail’s ban on Belfast Goods, organizing patrols, or acting as ‘Republican Police’ in apprehending criminal gangs. Arguably these operations were only passed as the Dublin Brigade was seriously under strength following the massive capture of members in the aftermath of the burning of the Customs House. O’Neill’s plan for what would have been the ICA’s most significant operation of that period of the War of Independence, involved an attack on an Auxiliary RIC’s amusement centre at Sydney Lodge, Booterstown. It seems much time, planning, and resources went into it, but as with other operations, it was “called off at the last moment.” Similar efforts went into a cancelled attack on Dublin Castle where the ICA worked directly under the orders of Volunteer HQ.

Given their size and resources the ICA’s overall record compares favorably to many Dublin based Volunteer Companies during that period. In 1913 Larkin had told Dublin to get off their knees and throughout 1917 the ICA under James O’Neill’s leadership had continued this message in conjunction with both the ITGWU and Michael Collins who was seen as being “close to the Labour fellows.” However, given the democratic nature of the ICA Army Council, the determination to maintain a particular ethos as the political lines blurred was impossible. When Stephens Green veteran and North Strand resident Frank Robbins returned from America in 1918 the cracks and divisions were already apparent. Robbins was returning strongly under the influence of the American based Fenian leader John Devoy. In 1917 Dr. Kathleen Lynn was elected Vice-President of the Sinn Fein Executive while retaining her role in the ICA. When she stood for election to Rathmines Urban Council the Citizen Army divided between affection for her and those who felt all their resources should go behind the election campaign of Socialist candidate Walter Carpenter. Countess Markievicz would be elected as a Sinn Fein MP in 1918 while maintaining her interest in both the ICA and the Fianna and sitting on the Army Council of both organizations. She signed her name ICA or IRA as the mood took her despite having been elected a Major and Chief of Staff of the ICA in July 1917. Tommy Shields, Joseph Doolin, Daniel King, and John Redmond, were members of both the ICA and IRB. Some would maintain a dual membership of both the ICA and IRA until this was banned in 1919.Larkinites such as Dick McCormick, Daniel Courtney, and Bob DeCoeur would see their role as backing up organized labour and would clash with the ITGWU executive on numerous occasions. When the ICA refused to sell Sean O’Casey’s history of the army because of inaccuracies it was ironic that O’Casey cited Dick McCormick as a major source of his information.

In the end, O’Neill appears to have become disillusioned. In 1919, he was jailed in Mountjoy following a sting operation involving the theft of a British Army Vehicle. On his release the various factions of Republicans, Communists, and Larkinite Labour men, who constituted the ICA were at each other’s throats. Christy Poole would resign. His brother Vincent would leave and join the IRA. Seamus McGowan was Courts Martialed and removed. The army council minutes’ show high profile members such as McCormick and DeCoeur being reprimanded. Jinny Shanahan, effective military commander of the women’s section in 1916, would complain that they were only being used for dirty work such as collecting money, selling flags, or distributing pamphlets. There was a vibrant social scene while the ICA were at Liberty Hall and the opportunity to meet the opposite sex seems to have been an attraction for some of the young new recruits. Meanwhile the IRA had set up The Labour Board, involving trade unionists such as William Kennedy, Robert Donohoe, Christopher Farrell, and Thomas Pugh. This was a secretive intelligence group which set out to undermine the British controlled Amalgamated Trade Union Societies operating in Ireland and pinpoint key workers in Power Stations, the Railways, and Docks who would be amenable to the IRA. A growing number of Transport Union officials were joining the Dublin Brigade and it seems that the IRA had already decided that the ICA’s labour connections were superfluous to requirements by 1918. An Auxiliary report on a raid on James O’Neill’s home at Marino Villa the following year records some rusted broken down vehicles in nearby sheds but very little sign of recent activity.

According to the family of James O’Neill, he was always more an admirer of Connolly rather than a hardcore Socialist. Without the charisma of a Connolly or Larkin it was always going to be difficult to hold the competing strands of the ICA together. While he had managed to keep the diverse elements on track up to 1919 the gap created by his imprisonment allowed the divisions to fester. His building business had all but ceased to function and at one stage he was forced to seek regular work as a carpenter on building sites. As the IRA took off following Soloheadbeg the ICA were being left behind in their wake competing for scraps. Even on intelligence work, as James O’Shea recorded, O’Neill had to defer to Collins and often would return with the permission to proceed on a job being refused. Again, and again he would explain that the ICA had to wait for the big one. In April 1921, the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade attacked the Auxiliary HQ at the London and North Western Hotel at the North Wall. This was a ‘big one’, in the heartland of what the ICA saw as their territory and was a major propaganda coup. There was not a single ICA member involved in the operation and as they took stock O’Neill’s caution to wait must have seemed hollow. Ultimately someone had to take the blame for that failure and to many ICA members O’Neill had just waited far too long.

In 1917, with the men of ’16 back and ready for action, the Irish Citizen Army were at the forefront of the resurgence. They had lost no time in declaring their intentions, and were quick to reorganize, re-arm and were standing out proud and defiant. By the early 1920’s their organization was in disarray, committed activists were looking elsewhere for action and they had become in effect a support group for and subservient to the Irish Republican Army. What had been part of their traditional heartland in the Dublin Docks was now largely the domain of the Dublin Brigade. While many of the Citizen Army stalwarts would remain committed and influential in the Trade Union and broader labour movement throughout the coming years, by the end of the War of Independence their days as a distinct and effective organization of the Irish working class had come to an end.

This article is based on our ongoing research into the Dublin Docklands community during the revolutionary period. If you have any further information, corrections or clarifications please contact

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

(We would like to thank Eamon Carpenter, Veronica Redmond, Dario Regazzi, Anthony Leisagang, Michael Poole, Grainne & Anne Keeley , Eilish Lynch , Phil Churchill, Elizabeth ‘Betty’ O’Brien and all others who shared family information which contributed to the research used in this article).