During World War One German U-boat activity in Irish Coastal Waters led to the loss of hundreds of vessels and thousands of lives. Torpedo attacks intensified in 1917 and that year’s Christmas season would be a grim one many families. December saw the sinking of a Dublin Port ship, the SS Hare, on December 14th, with the loss of 12 lives. A fortnight later the SS Adela would become the latest victim, with the loss of 24 lives (14 of them from the Dockland communities). This is the story of that last voyage. This account is adapted from Chapter 8 of “U-Boat Alley”, with the kind permission of author Roy Stokes:

Christy Wolfe, a ship’s stoker who lived in one of the small terraced cottages adjacent to North Wall, boarded the SS Adela well before the last of the livestock and cargo had been loaded, and apart from the drovers who occupied the steerage, only one other passenger boarded. Although steam had been up for over an hour, departure was delayed until nearly 5 o’clock, when she slipped her ropes from the wall at City Quay. The delay may have been caused by ‘awaiting Admiralty instructions’, without which most vessels could not sail. Given the all clear, Dublin’s lights faded behind her as she steamed down the River Liffey on what was to be her last journey across the Irish Sea.

Approximately three hours prior to the SS Adela’s departure from the River Liffey, Commander Kapitänleutnant Freiherr Degenhart von Loë of U-100 was already counting the cost of a lean patrol. Of the two torpedoes fired for the duration of his patrol hitherto, the first had just missed one of the two steamers in “Quadrant 37” in the Irish Sea. The reason he gave for this failure was that he was too close, and the torpedo passed under the target. This was almost certainly the ship – sent to the bottom ten months later on 10 October 1918, with such a dreadful loss of life. The packed mail boat, RMS Leinster, recorded this near-miss after leaving Holyhead on the 27th. Commander von Loë fired only one more torpedo for the remainder of his cruise but the second one did not miss its target.

At 11.40 PM, Commander von Loë positioned his submarine on the surface a few miles northeast of ‘The Skerries’ near the Isle of Anglesey, Holyhead. The steamer SS Adela was on a course only 350 meters to the South of him, heading for Liverpool. At 11.50 P.M., U-100 submerged and fired one torpedo from tube IV, hitting the approaching vessel amidships on the starboard side. Commander von Loë later reported that the vessel was ‘heavily loaded’, and was about 2,000 tons .

The light often played tricks with the apparent size and interpretation of the targets at sea, but U-boat commanders were also well known for a tendency to exaggerate the size of their ‘hits’ in order to impress their superiors. Commander von Loë observed the final moments of the SS Adela through the submarines periscope and recorded this brief epitaph:

‘Steamer breaks in the front bridge and sinks immediately. According to her shape she must have been a tanker with three masts, tall bridge in the middle, no guards noticed.’

The description given of von Loë’s victim does not seem to fit the SS Adela, but there were no other losses recorded in that area on that night, and it is to U-100 that the sinking of the SS Adela is accredited.

Not unaware of, but removed from, the struggles that were being acted out on the surface by the surviving crew members from the Adela, U-100 and her crew stole silently away into the night, leaving behind a scene of total carnage. Before she finally disappeared, however Captain Tyrell caught sight of the retreating submarine. The next day, Commander von Loë was still in the vicinity but fled when a destroyer came into view.

Many vessels and their crews perished and disappeared without trace, but from the mangled wreckage of the SS Adela, a lone sailor managed to live and tell the tale of the ship’s final moments. Captain Tyrell was the only survivor, and he was badly affected by the experience, and spoke very little of it again.

It is extremely difficult to picture the scene, or to understand what went on in the minds of the survivors as they struggled for life in the middle of a dark, cold sea. The story unfolds, however, with the help of censored articles and the available reports on the inquest held for four of the crewmen. Theirs were the only bodies recovered.

Several days later, there was an unusual display of grief by the coroner, who ‘burst into tears’ during his summing up of the inquest. He described the incident as ‘the enemy’s treachery’. Captain Tyrell was also overcome during the proceedings at Holyhead, when he testified that the crew had ‘all discharged of their duties faithfully

The night was described as ‘moonlight’, and the sea as ‘choppy but not rough’. As soon as the SS Adela had cleared the Dublin Channel buoys, she would have probably increased her speed to the normal maximum, which might have been as much as nine or ten knots. This meant that she would have cleared the Kish Light Vessel a little later than 6 o’clock. Not all masters followed their instructions to steer a zigzag course and to keep lights extinguished, or to sail with their lifeboats slung out. And it is not clear what instructions were given to the crew in this respect on the night.

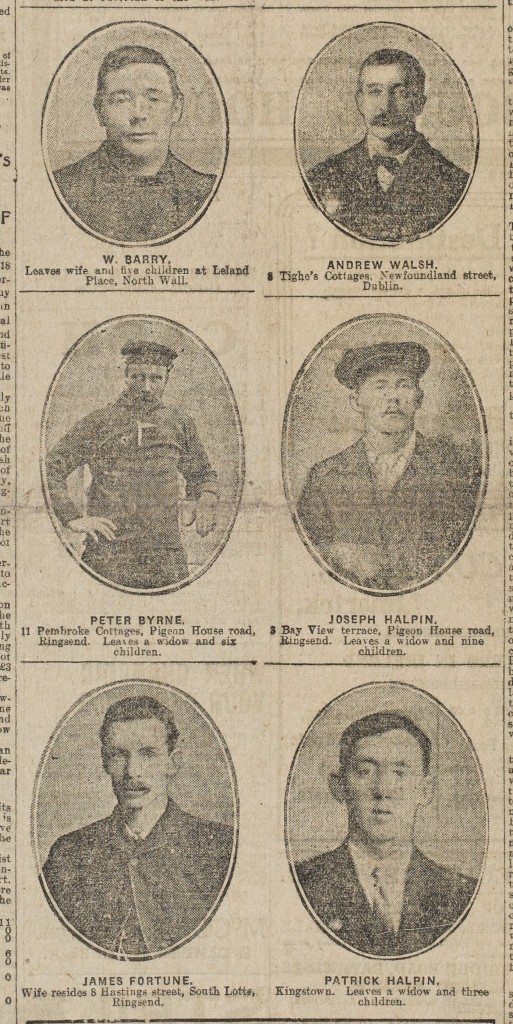

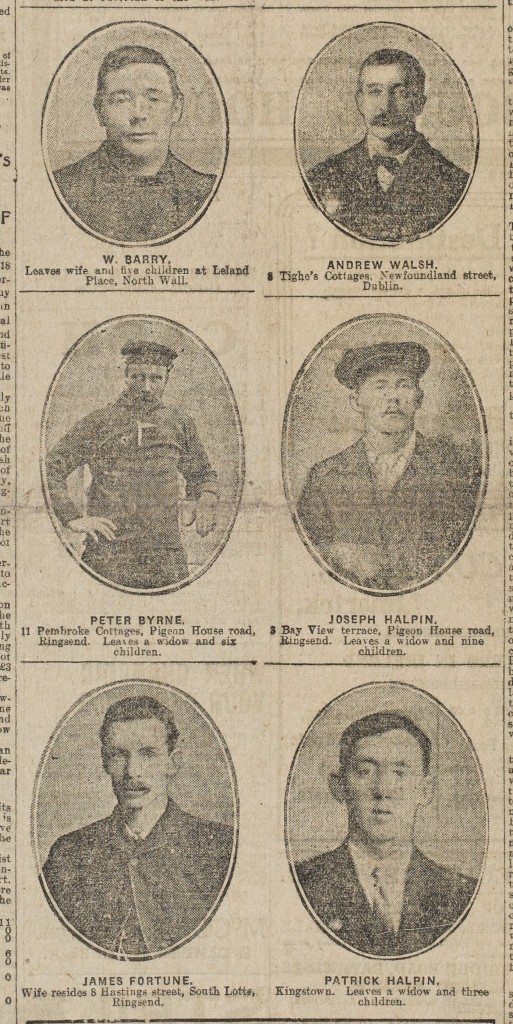

Some of the lost crew members (Evening Herald January 1918)

Little is known about shipboard activity on the SS Adela during that night, other than what would have been the crew’s ordinary duties. Together with tea and chat, gunner and sailor customarily found friendship in the galley. The crossing would normally have lasted about eight to ten hours, during which time some of the crew would have taken the opportunity to retire to their bunk for some sleep, and others might just have chatted for the duration of their free time.

As the ship approached the ‘The Skerries’, one might expect the crew to have considered the sight of land to be a godsend, heralding the imminent escape from the dangers of open water. This was not the case, and in fact, this particular area was probably considered to be the most dangerous part of the whole journey. The U-boats were well known to regularly lie in wait off Anglesey, and the number of shipwreck symbols speckled on the Admiralty chart for this area is testimony to the slaughter of merchantmen that took place there during World War 1.

The only passenger , and only woman on-board.

The attack took place at 11.50p.m., and pandemonium erupted on the ship. The loud explosion caused by the torpedo hitting the ship was immediately recognised by the crew for what it was. The little steamer suddenly became a sinking mass of twisted metal and strewn animal carcasses. The SS Adela snapped in two just forward of the bridge, and she began to sink immediately. The lifeboats had not been slung out, and those that were not damaged in the violent explosion crashed onto the deck. There was only one lifeboat reported to have survived the explosion; the captain and four others scrambled into it. It had landed on the deck, and floated off when the ship began to sink.

The SS Adela had just disappeared when U-100 approached the scene of devastation, and it was at this time that Captain Tyrell later recalled that he got ‘a momentary glimpse of the enemy craft stealing away in the gloom of the night.’

The members of the crew who survived the explosion, and managed to reach the lifeboat, were soaked, battered, and soon freezing cold. Lethargy and a mood of haplessness, brought about by the condition of hypothermia, soon swept over them. It was only two days after the Christmas celebrations when SS Adela’s only survivors found themselves helplessly adrift in a small lifeboat, bobbing abut in the dark amongst the remainder of the struggling livestock. The wretched animals lasted only a short time, and the occupants of the small life boat bravely struggled to rescue two more crew from the freezing water.

The lifeboat had been damaged when it was wrenched from its davits, and needed exhaustive baling in order for it to remain afloat.Three of the men were utterly helpless but not quite dead when they were washed out of the lifeboat ‘in their senses’ before a destroyer arrived on the scene at 2.00 p.m. the following day. Three of the remaining survivors had died, and a fourth succumbed soon after.

(Date of death for the following men is listed as 28th December, and cause of death recorded as exposure: Samuel Burrowes, Patrick Corcoran, Alexander Donaldson, John Mackey, Francis Mangan and Andrew Walsh).

Captain Tyrell’s long experience at sea, and his strong build, probably saved him, as he was later described by an Irish Independent reporter as being a ‘typical master mariner, a man of powerful physique’.

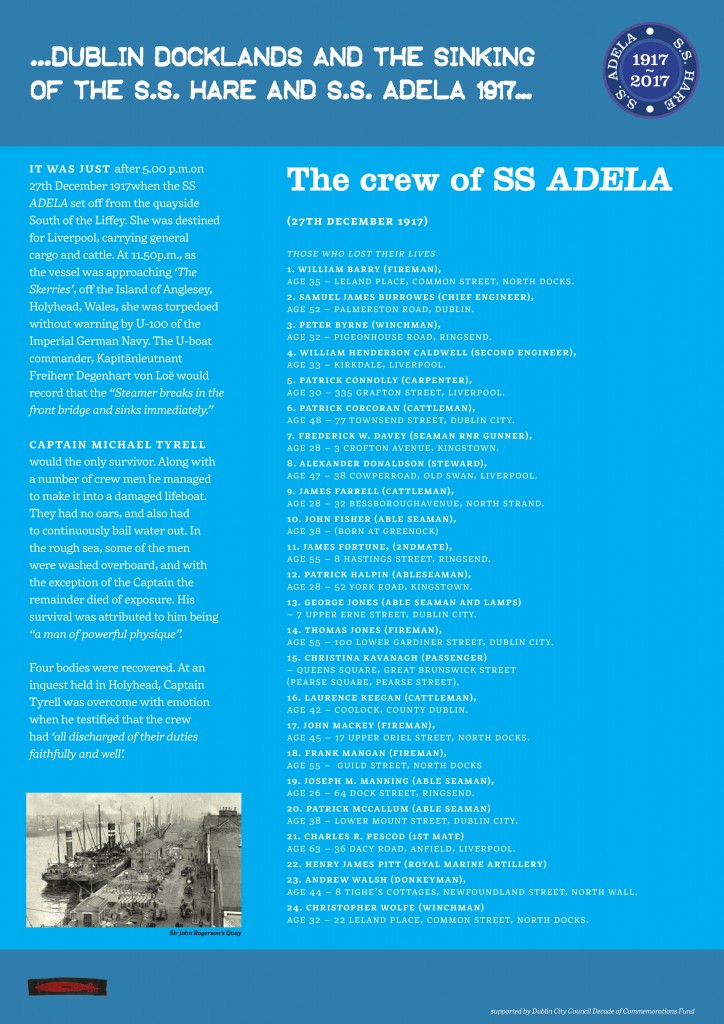

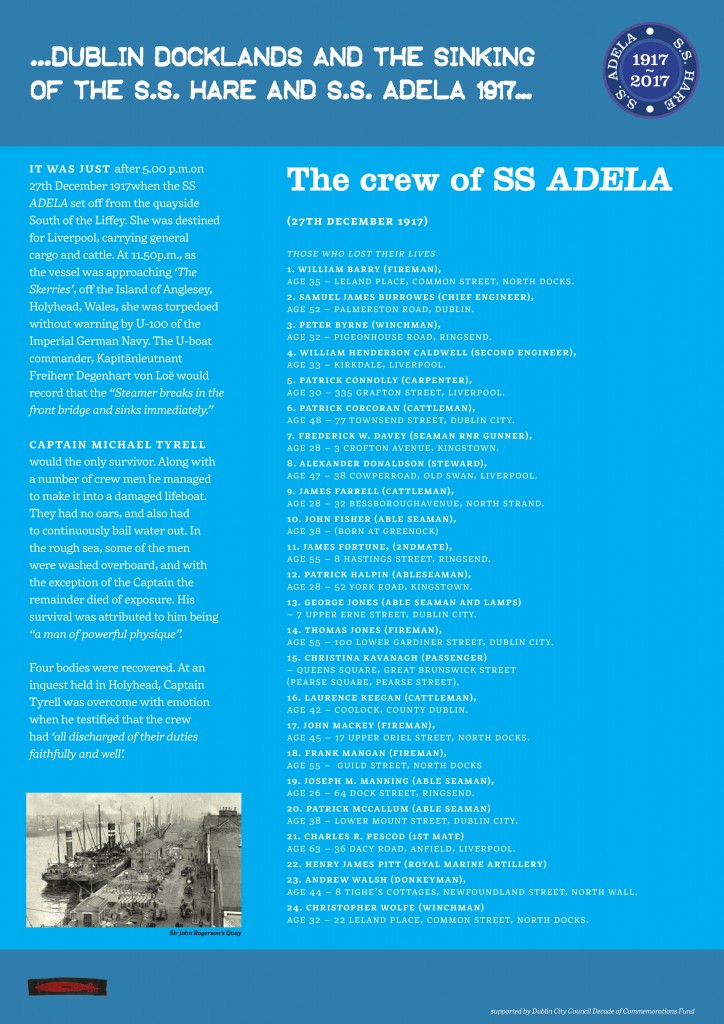

Panel from centenary exhibition.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…”, published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information, corrections, clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

Image credits :

SS Adela postcard – courtesy Ian Lawler

SS Adela plaque – Patrick Hugh Lynch