Jan 28

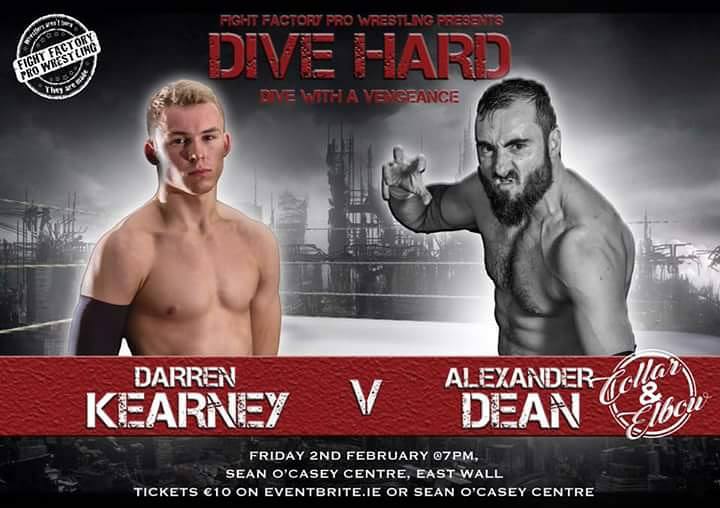

Local star features in Pro Wrestling Show : February 2nd @ the Sean O’Casey Centre

Following on from their sell out shows last year “Fight Factory Pro Wrestling” returns to the Sean O’Casey Centre next Friday ( 2nd February) @ 7pm . An evening of hard hitting action suitable for all ages , the big news is that local talent Darren Kearney will compete on the show. He has already made a name for himself on the growing Irish Pro Wrestling scene , and last year spent time at the famous Storm Wrestling Academy in Canada. This is his first appearance in his home community since returning so come out and support a local who is going to be a huge star .

Following on from their sell out shows last year “Fight Factory Pro Wrestling” returns to the Sean O’Casey Centre next Friday ( 2nd February) @ 7pm . An evening of hard hitting action suitable for all ages , the big news is that local talent Darren Kearney will compete on the show. He has already made a name for himself on the growing Irish Pro Wrestling scene , and last year spent time at the famous Storm Wrestling Academy in Canada. This is his first appearance in his home community since returning so come out and support a local who is going to be a huge star .

Jan 14

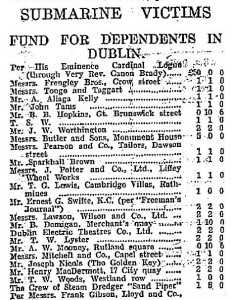

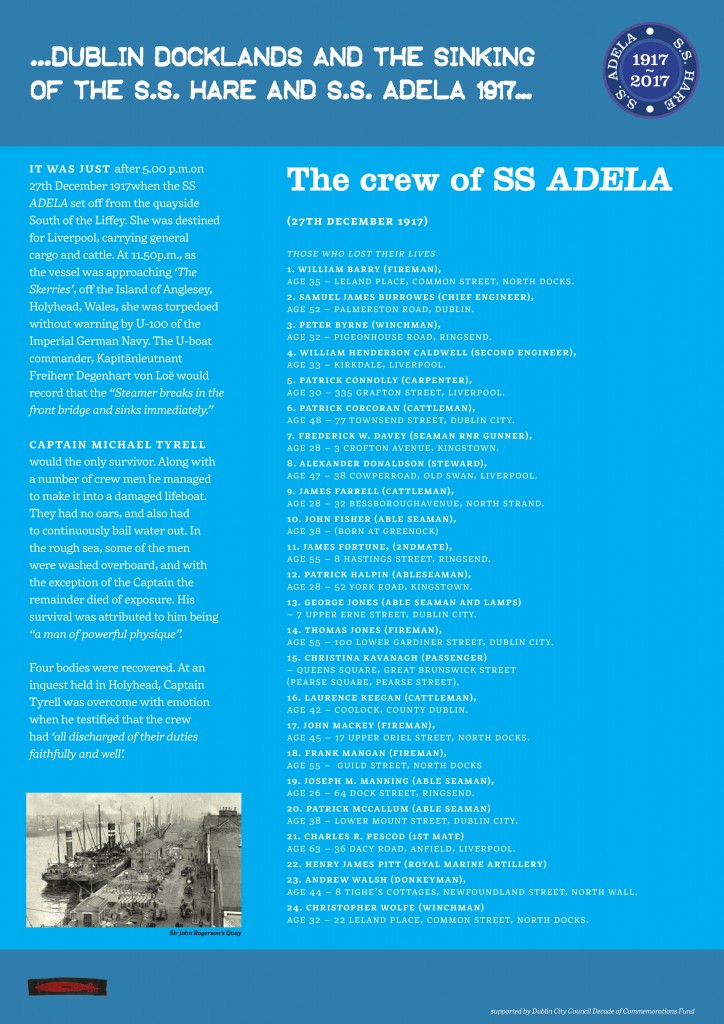

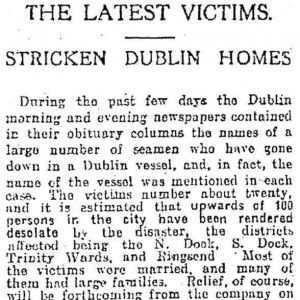

WW1 SUBMARINE VICTIMS : HELP FOR DEPENDENTS IN DUBLIN

“It has been estimated that upwards of 100 persons in the city have been rendered desolate by the disaster”

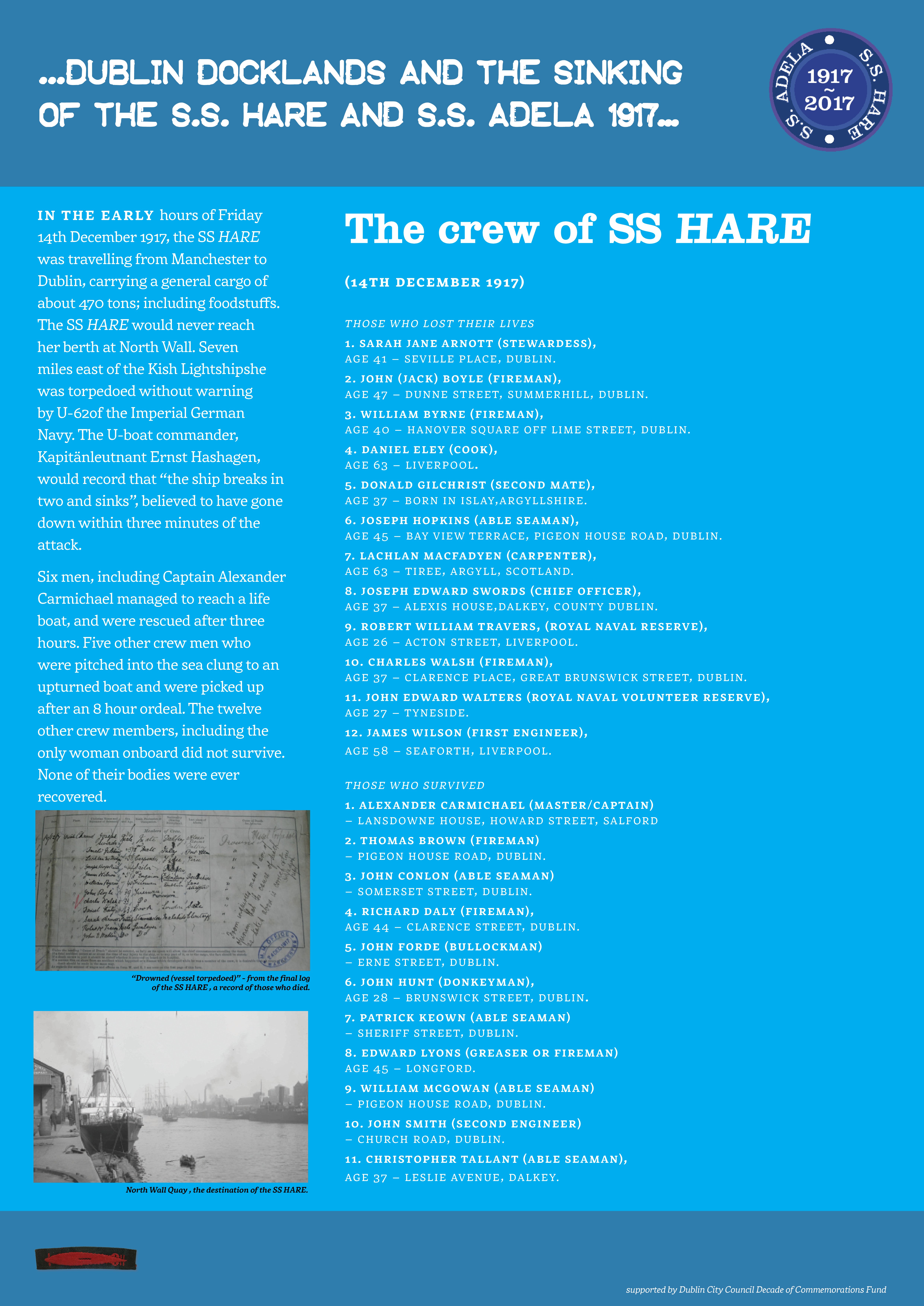

On the 14th December 1917 the SS Hare was torpedoed as traveled from Manchester to Dublin Port , with the loss of 12 lives. Just a fortnight later the SS Adela was similarly targeted as it traveled from Dublin to Liverpool , with the loss of 24 lives. As the New Year of 1918 got underway , the population of Dublin City rallied around to support the families of those who had died.

Due to war-time censorship the initial press reports did not name the vessels or refer to U-boats as the cause of the ‘tragedy’ or ‘loss’. In the closely knit Dockland and seafaring community they knew. The effect of the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela was seismic, with the ripples quickly spreading through the business community of the city. From the start of the war deaths of Docklands dwellers in far off places such as Gallipoli, the Somme, and Passchendaele had been regular, and it was not uncommon for ships to fall victim off the Irish coast. 159 ships were sunk in Irish coastal waters during 1917. However, the majority of these were sunk off the Atlantic coast, and though the Irish channel had become increasingly hostile, these Christmas season attacks brought home the reality of war like never before. The impact can be seen in the tremendous support effort in the aftermath, where literally the whole population played a role, from the richest business owners to the poorest quay side labourers, from those who built the ships to those who sailed them, from trade union leaders to captains of industry, and crossing all religious and political divides.

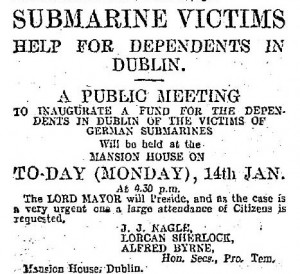

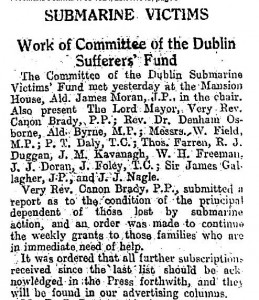

In early January several influential politicians, trade unionists, and businessmen met at the Mansion House to set up a Submarine Victim’s Fund for the dependents of those lost at sea. A public meeting was held three days later and over the next six months substantial funds were raised. Although not complete, from the published lists we can get some sense of the reality check which hit, as the community began to realise that nobody was safe even on the short trips across the Irish Sea.

Among the first individual donors was Walter Scott of the Dublin Dockyard Company. Irish Shipbuilding was booming during the war, led by Belfast’s Harland and Wolfe. That city’s “wee yard” at Workman Clarke was setting world records in building a new simplified transport craft to replace the numerous ships being sunk each month. The smaller Dublin Dockyard Company was struggling to meet orders due to a shortage of space and lack of skilled men. This was so serious that a blind eye was being turned to former staff who had fought in the 1916 Rising as craftsmen were in such short supply. The Company itself gave £100 while the workforce, dividing along their trade union lines each gave individual donations amounting to over £50.

Local dockland based companies, reliant on ships for exports and imports, made donations –Barrington’s Soap Factory on Sheriff Street, Ross & Wallpole Iron Founders, The Dublin Glass Bottle Company, Boland’s Bakery, T. & C. Martin, Timber Merchants, Cherry & Smaldridge Printers, on Seville Place, Goulding’s Fertilizer Company, Smith & Pearson, British Petroleum (originally a German Registered Company) and many others.

Municipal employees were generous-Dublin Corporation Main Drainage workers at the Pigeon House Fort donated as did their colleagues at the Pigeon House Pump Station, and the adjacent Electrical Power Station. So too did those at the Pump Stations on East Road and Forbes Street.

Those engaged in transport, both seafaring and dockside, were affected, and most would have known the victims and their families. The Dublin Steam Trawler Company donated as did the Captains and crews of the SS Carlow, SS Belfast, and SS Yarrow. Many of their crew members had previously served on both the Adela and Hare. The crew of the Corporation dredger SS Shamrock gave funds as did the Irish Ships Firemen’s Trade Union and the Irish Stationary Engine Drivers Union, which represented crane-men on the docks. Dublin Port’s Harbour Master, John Henry Webb, and his assistant James Brady contributed (as did Brady’s brother, the MP for St.Stephen’s Green, Patrick Joseph Brady). The workers club of the Midlands Great Western Railway also supported the cause along with many other businesses and workforces North and South of the Liffey. Hauliers such as Wallis and Pickfords also appear on the lists. Most of these workers were earning war bonuses and there was no shortage of work. With the sinking of these well-known vessels, the reason for this became only too apparent.

Entertainment and sporting bodies were called upon to support these efforts and responded magnificently. The Queen’s Theatre performed a matinee of their successful pantomime, Tom Thumb, which raised £48. The Royal Theatre then staged a benefit night which brought in £272.Whippet races were organized at Shelbourne Park raising £66; The Leinster Football Association granted permission for fundraising matches to be played in March and April; Gold Clubs organized dances, bands played concerts, Picture Houses such as the Rotunda, Camden, and Phoenix Picture Palace all donated takings, and in June, the Committee in charge of the Irish Derby Sweep, run at Baldoyle, announced that they were donating £1400 to the cause.

In the wider business community donations were received from many of the leading departments stores and business such as Arnotts, Switzers, Findlaters, the Varian Brush Company, Dockrell’s, Pimm’s Department Stores, individual donations from each of the Eason brothers, and many more besides. Jameson’s and Power’s Distillers, The Mountjoy Brewery, and Guinness (all involved in exporting their products) were not found wanting. Guinness coopers made a separate donation. The Car Company Ashenhurst Williams and the Iron Founders Thompsons (both engaged in wartime manufacturing), are also on the list. Hopkins and Hopkins Jewellers, The Irish Times, even William Martin Murphy of Independent Newspapers all donated as did hundreds of individuals from all over Ireland and Britain.

The response crossed the religious divide. Canon Brady of St Laurence O’Tooles parish was one of the originators of the fund, with many of the victims and their dependents coming from his parish. His Co-organiser, Rev. Dr. Denham Osbourne of Rutland Square Presbyterian Church received numerous donations from amongst his co-religionists, while many parishioners from the three main religions contributed through their Parish Priest, Rector, or Minister. The Irish Jewish Association made a generous donation and then over 50 individual Jewish Businessmen also contributed.

The largest business contribution came in January from the Irish Cattle Traders and Stockowners Association and amounted to £1,100. Michael Cuddy of their Committee was from Seville Place and an extensive exporter of cattle and sheep. Cuddy’s family had a Butchers Shop at Spencer Dock Bridge, and it’s likely that he knew many of those that died and their families, having employed them at one time. Both the SS Adela and SS Hare had cattle drovers among their crew. The sinking of the RMS Leinster in October 1918 has historically overshadowed the loss of the Adela and the Hare. However, from the subscription lists we can see how far reaching the consequences were after the sinking of the latter two ships. Both ships were sailing in what should have been safe waters. Now all was changed and the reality of it would reverberate not just through the victim’s relatives but right through the entire population of Dublin and beyond.

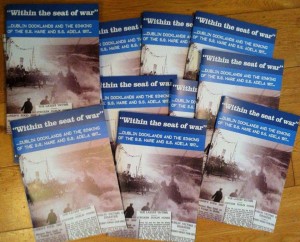

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” , published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information , corrections , clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

Jan 07

Centenary of Dublin Port ships lost in U-Boat attacks : Two plaques unveiled

December 2017 marked the centenary of U-boat attacks on two well known Dublin Port ships . Almost half of those who died when the SS Hare and SS Adela were torpedoed came from the Dublin Dockland communities. The tragedies were marked by a number of events, commemorated by the Adela- Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee. This group was made up of local history and community groups , working alongside descendants of the original crew members . These two videos show the ceremonies to unveil plaques to each vessel and their crew .

The ceremonies were led by the Lord Mayor of Dublin Ardmhéara Mícheál MacDonncha , and the unveilings were conducted by descendants of crew members of the SS Hare and SS Adela . The Dublin City Council plaques were approved by the Commemorative Naming Committee , and the initiative was supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemorations Fund.

Video produced by Eoin McDonnell (Supported by Dublin Central 1917 Commemoration Project Fund)

A 48 page book telling the story of Dublin Port during World War One, the danger posed by Submarine attacks and particularly the SS Hare and SS Adela tragedies was also produced as part of the centenary commemoration. We are anxious to talk to any families related to the crew members , and including any new material in future publications and exhibitions. Contact us at

adelahare1917@gmail.com

Dec 27

The final Voyage of the SS Adela – 27th December 1917

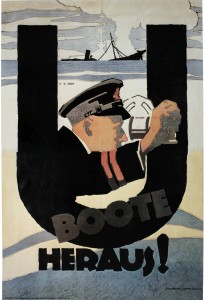

During World War One German U-boat activity in Irish Coastal Waters led to the loss of hundreds of vessels and thousands of lives. Torpedo attacks intensified in 1917 and that year’s Christmas season would be a grim one many families. December saw the sinking of a Dublin Port ship, the SS Hare, on December 14th, with the loss of 12 lives. A fortnight later the SS Adela would become the latest victim, with the loss of 24 lives (14 of them from the Dockland communities). This is the story of that last voyage. This account is adapted from Chapter 8 of “U-Boat Alley”, with the kind permission of author Roy Stokes:

Christy Wolfe, a ship’s stoker who lived in one of the small terraced cottages adjacent to North Wall, boarded the SS Adela well before the last of the livestock and cargo had been loaded, and apart from the drovers who occupied the steerage, only one other passenger boarded. Although steam had been up for over an hour, departure was delayed until nearly 5 o’clock, when she slipped her ropes from the wall at City Quay. The delay may have been caused by ‘awaiting Admiralty instructions’, without which most vessels could not sail. Given the all clear, Dublin’s lights faded behind her as she steamed down the River Liffey on what was to be her last journey across the Irish Sea.

Approximately three hours prior to the SS Adela’s departure from the River Liffey, Commander Kapitänleutnant Freiherr Degenhart von Loë of U-100 was already counting the cost of a lean patrol. Of the two torpedoes fired for the duration of his patrol hitherto, the first had just missed one of the two steamers in “Quadrant 37” in the Irish Sea. The reason he gave for this failure was that he was too close, and the torpedo passed under the target. This was almost certainly the ship – sent to the bottom ten months later on 10 October 1918, with such a dreadful loss of life. The packed mail boat, RMS Leinster, recorded this near-miss after leaving Holyhead on the 27th. Commander von Loë fired only one more torpedo for the remainder of his cruise but the second one did not miss its target.

At 11.40 PM, Commander von Loë positioned his submarine on the surface a few miles northeast of ‘The Skerries’ near the Isle of Anglesey, Holyhead. The steamer SS Adela was on a course only 350 meters to the South of him, heading for Liverpool. At 11.50 P.M., U-100 submerged and fired one torpedo from tube IV, hitting the approaching vessel amidships on the starboard side. Commander von Loë later reported that the vessel was ‘heavily loaded’, and was about 2,000 tons .

The light often played tricks with the apparent size and interpretation of the targets at sea, but U-boat commanders were also well known for a tendency to exaggerate the size of their ‘hits’ in order to impress their superiors. Commander von Loë observed the final moments of the SS Adela through the submarines periscope and recorded this brief epitaph:

‘Steamer breaks in the front bridge and sinks immediately. According to her shape she must have been a tanker with three masts, tall bridge in the middle, no guards noticed.’

The description given of von Loë’s victim does not seem to fit the SS Adela, but there were no other losses recorded in that area on that night, and it is to U-100 that the sinking of the SS Adela is accredited.

Not unaware of, but removed from, the struggles that were being acted out on the surface by the surviving crew members from the Adela, U-100 and her crew stole silently away into the night, leaving behind a scene of total carnage. Before she finally disappeared, however Captain Tyrell caught sight of the retreating submarine. The next day, Commander von Loë was still in the vicinity but fled when a destroyer came into view.

Many vessels and their crews perished and disappeared without trace, but from the mangled wreckage of the SS Adela, a lone sailor managed to live and tell the tale of the ship’s final moments. Captain Tyrell was the only survivor, and he was badly affected by the experience, and spoke very little of it again.

It is extremely difficult to picture the scene, or to understand what went on in the minds of the survivors as they struggled for life in the middle of a dark, cold sea. The story unfolds, however, with the help of censored articles and the available reports on the inquest held for four of the crewmen. Theirs were the only bodies recovered.

Several days later, there was an unusual display of grief by the coroner, who ‘burst into tears’ during his summing up of the inquest. He described the incident as ‘the enemy’s treachery’. Captain Tyrell was also overcome during the proceedings at Holyhead, when he testified that the crew had ‘all discharged of their duties faithfully

The night was described as ‘moonlight’, and the sea as ‘choppy but not rough’. As soon as the SS Adela had cleared the Dublin Channel buoys, she would have probably increased her speed to the normal maximum, which might have been as much as nine or ten knots. This meant that she would have cleared the Kish Light Vessel a little later than 6 o’clock. Not all masters followed their instructions to steer a zigzag course and to keep lights extinguished, or to sail with their lifeboats slung out. And it is not clear what instructions were given to the crew in this respect on the night.

Little is known about shipboard activity on the SS Adela during that night, other than what would have been the crew’s ordinary duties. Together with tea and chat, gunner and sailor customarily found friendship in the galley. The crossing would normally have lasted about eight to ten hours, during which time some of the crew would have taken the opportunity to retire to their bunk for some sleep, and others might just have chatted for the duration of their free time.

As the ship approached the ‘The Skerries’, one might expect the crew to have considered the sight of land to be a godsend, heralding the imminent escape from the dangers of open water. This was not the case, and in fact, this particular area was probably considered to be the most dangerous part of the whole journey. The U-boats were well known to regularly lie in wait off Anglesey, and the number of shipwreck symbols speckled on the Admiralty chart for this area is testimony to the slaughter of merchantmen that took place there during World War 1.

The attack took place at 11.50p.m., and pandemonium erupted on the ship. The loud explosion caused by the torpedo hitting the ship was immediately recognised by the crew for what it was. The little steamer suddenly became a sinking mass of twisted metal and strewn animal carcasses. The SS Adela snapped in two just forward of the bridge, and she began to sink immediately. The lifeboats had not been slung out, and those that were not damaged in the violent explosion crashed onto the deck. There was only one lifeboat reported to have survived the explosion; the captain and four others scrambled into it. It had landed on the deck, and floated off when the ship began to sink.

The SS Adela had just disappeared when U-100 approached the scene of devastation, and it was at this time that Captain Tyrell later recalled that he got ‘a momentary glimpse of the enemy craft stealing away in the gloom of the night.’

The members of the crew who survived the explosion, and managed to reach the lifeboat, were soaked, battered, and soon freezing cold. Lethargy and a mood of haplessness, brought about by the condition of hypothermia, soon swept over them. It was only two days after the Christmas celebrations when SS Adela’s only survivors found themselves helplessly adrift in a small lifeboat, bobbing abut in the dark amongst the remainder of the struggling livestock. The wretched animals lasted only a short time, and the occupants of the small life boat bravely struggled to rescue two more crew from the freezing water.

The lifeboat had been damaged when it was wrenched from its davits, and needed exhaustive baling in order for it to remain afloat.Three of the men were utterly helpless but not quite dead when they were washed out of the lifeboat ‘in their senses’ before a destroyer arrived on the scene at 2.00 p.m. the following day. Three of the remaining survivors had died, and a fourth succumbed soon after.

(Date of death for the following men is listed as 28th December, and cause of death recorded as exposure: Samuel Burrowes, Patrick Corcoran, Alexander Donaldson, John Mackey, Francis Mangan and Andrew Walsh).

Captain Tyrell’s long experience at sea, and his strong build, probably saved him, as he was later described by an Irish Independent reporter as being a ‘typical master mariner, a man of powerful physique’.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…”, published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information, corrections, clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

Image credits :

SS Adela postcard – courtesy Ian Lawler

SS Adela plaque – Patrick Hugh Lynch

Dec 26

The life of the SS Adela : A Tedcastle ship (1878 – 1917)

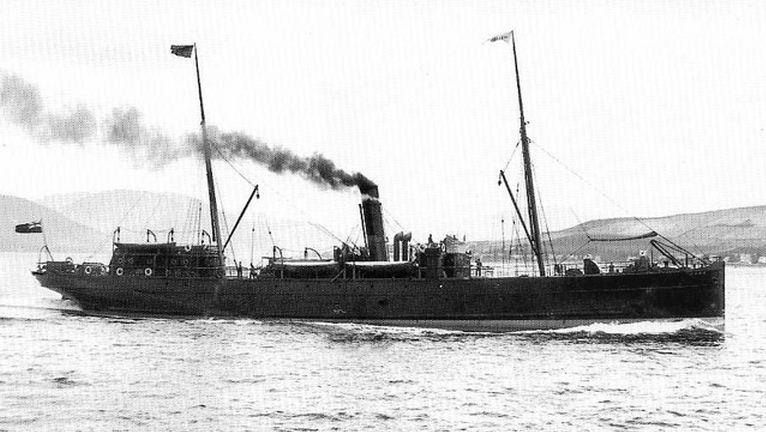

The SS Adela was built in 1878 by Henry Murray and Co. at their Glasgow yard. The steamer was almost two hundred feet long with a gross tonnage weight of 685. Built for Robert Tedcastle, the Vessel was intended for the cross-channel passenger and cargo trade. Constructed with the most modern innovations for the handling of livestock, and with improved cabin space for the number of fare-paying passengers and twenty-one crew, she would prove to be very popular ship on the Dublin-Liverpool route, which she served until 1917.

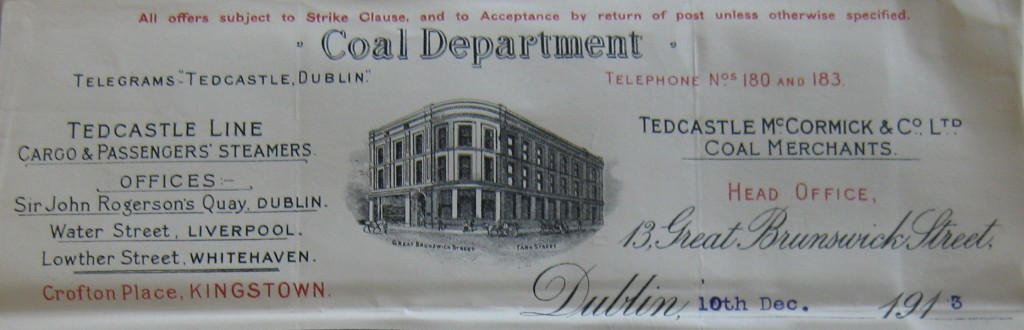

Robert Tedcastle had been born in Dumfriesshire, Scotland in 1825. He moved to Dublin and became involved with his uncle’s coal business. A successful endeavour, by the 1840’sit moved into the cross-channel shipping of their product. When his uncle returned to Scotland, Robert remained and operated a growing fleet of sail and steam ships. His first steamer, the SS Dublin, was supplied in 1866 by the Dublin yard of Walpole Webb & Co. Tedcastle’s ships eventually entered passenger and general cargo service on the Dublin-Liverpool route in 1872. His nephew John Tedcastle also joined the family business, and they would come to own an impressive fleet. In1897, they brought this with them when Robert Tedcastle & Co. would become partners with Dublin coal merchants McCormick & Co., leading to the creation of Tedcastle McCormick & Co. Ltd.

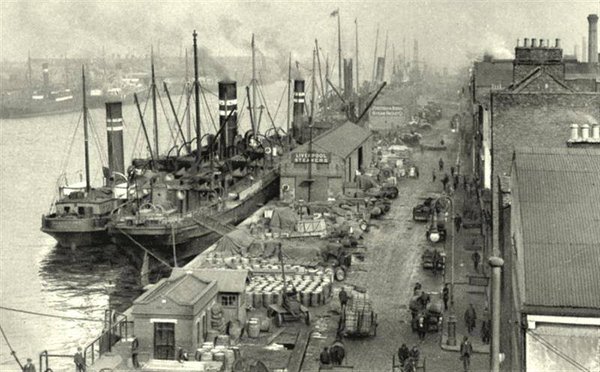

Robert Tedcastle was one of Dublin City’s most successful businessmen. His ships operated from their berths opposite his premises on Sir John Rogerson’s Quay. The adjoining properties on the quayside were occupied by some of the best-known shipping companies of the day.In addition to owning and renting the adjoining houses on Lime Street and Brady’s Court, he also acquired extensive farmlands in Australia. In 1864 the family had purchased their house and estate at Marlay Park, Rathfarnham, where they remained until his death in 1919.

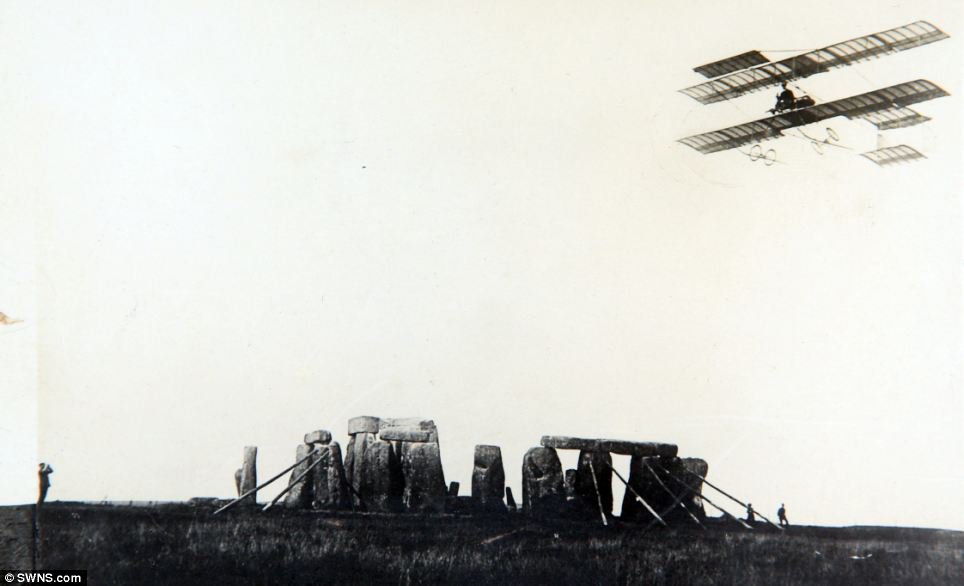

In 1910 the SS Adela would take part in a unique rescue mission, which gave it a supporting role in another historic event. Robert Loraine was a successful London and Broadway stage actor & manager. Among his most notable successes was introducing the George Bernard Shaw play “Man and Superman” to Broadway in 1905. He also had a great interest in the new technology of aviation (being the first person to fly in a rainstorm), and on 11th September 1910 he made what is credited as being the first aeroplane flight from England to Ireland, though his craft actually came down in the Irish sea about 200 feet from the shore . And this is where the SS Adela comes in:

“It struck the water about 60 yards from the shore near the Bailey lighthouse. Lorraine, who was wearing a life belt, swam toward the lighthouse from which a boat put out. Soon afterward the Dublin steamer Adela lowered a boat and drew the partially submerged aeroplane to the side of the steamer. After reaching the lighthouse Loraine set out again in a boat for the Adela and superintended the hoisting of his aeroplane to her deck. He found the injury to the machine was slight. The engine was in perfect condition”.

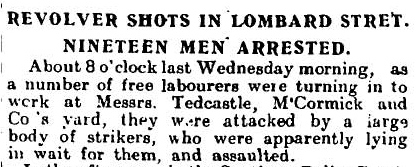

During the Great Lockout of 1913 the Company would gain some notoriety, though theirs is a story in stark contrast to that of the SS Hare and its voyage of hope. As the dispute began, Tedcastle & McCormick sacked workers for refusing to deliver coal to a Coolock farmer who was refusing to recognise the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU). One hundred further employees refused to carry out deliveries until their colleagues were reinstated, and these were quickly sacked too. The situation would quickly escalate and explode into violence, with the Company and those it hired to replace its workforcebeing associated with some particularly nasty incidents.

Tedcastle & McCormick were among the Dockland companies which would employ strike breakers brought into the City specifically for this purpose. Described officially as Free-Labourers, though more commonly known as scabs,these men were often armed with revolvers,and these were used recklessly and on occasion with lethal effect.

Tensions came to a head when a full-scale riot broke out in the vicinity of Townsend Street and Lombard Street on the morning of the 21st January 1913 when strikers ambushed and clashed with up to eighty strike breakers going to work at Tedcastle’s and shots were fired on the street.One of the most tragic occurrences during this period was the shooting of 16-year-oldAlicia Brady. She was returning with a food parcel from Sir John Rogerson’s Quay for her family at Luke Street, off Poolbeg Street when she was injured by a ‘free labourer’who fired two shots into a crowd jeering him, dying from her wound two weeks later. Both Jim Larkin and James Connolly spoke at her graveside, the latter stating, “Every scab and every employer of scab labour in Dublin is morally responsible for the death of the young girl we have just buried”. Patrick Traynor was charged with murder but found not guilty.

Thomas Harten was a County Meath man working for Tedcastle & McCormick. He was staying on Beresford Place at “The Barracks”, accommodation provided by the Employer’s Federation specifically for strike breakers, located dangerously close to ITGWU headquarters at Liberty Hall. Harten and a companion had enjoyed a Saturday evening on the town, when at 10.30 p.m.they were accosted on Eden Quay and beaten by a group of men. Harten would die, his head ‘crushed like an eggshell’. Thomas Harten had been in the city just six weeks, and that afternoon had bought himself a revolver. A number of strikers were arrested and a North Dock man, Tom Daly was charged with his murder but was eventually acquitted.

The SS Adela continued to sail the Dublin – Liverpool route without any significant incidents until 1917. The log records only minor matters. Charles Pescod had served on Tedcastle vessels since at least 1880 and was 1st Mate on the SS Adela since he joined the crew in 1900. Himself and Captain Tyrell seemed to be particularly diligent, and regular safety checks are signed by both men –

“Life boats swung out & crew exercised. All gear working well. Life saving appliances examined & in good order”.

The torpedo attack on 27th of December 1917 led to the damage of the lifeboats and all were smashed except one. Unfortunately those who made it into this boat would still not survive their ordeal, except for Captain Tyrell, the sole survivor of the final voyage.

In 1919 the Tedcastle & McCormick fleet came under the control of British & Irish Steampacket Company. The company continued operating as coal merchants. The company, which was founded during the age of the sailing ship has progressed over the two centuries of its existence, and is now Top Oil, still retaining a presence in Dublin Port, at Promenade Road.

For further information , corrections or clarifications please contact : adelahare1917@gmail.com

Dec 13

The final voyage of the SS Hare – 14th December 1917

The SS Hare set sail from Manchester to make the journey to Dublin on the evening of Thursday 13th December 1917. It was a familiar route for the steamer, one it had regularly travelled over the previous two decades, with many of the crew being old hands onboard. She was carrying a general cargo of about 470 tons, including foodstuffs. As a British Merchant Navy ship, it carried light armaments for protection. Accordingly there were two Gunners, of the Royal Naval Reserve, in addition to the ship’s crew. There were no additional passengers on board.

As the ship approached Dublin, 1st Officer Joseph Swords and Able Seaman Christopher Tallant were on the bridge. AB Tallant survived the catastrophe that was about to unfold, and would recount the final moments before the ship was struck: He had spotted a vessel which appeared about 100 yards aft. The chief officer went to the starboard side with the glasses, and had a look at her.”She is travelling fast” was all Joseph Swords had time to say, before the impact. Tallant was ‘knocked senseless from the wheel’ and ‘saw the chief officer no more’. The SS Hare had been torpedoed without warning by the submarine U62 of the Imperial German Navy, under the command of Kapitan Lieutenant Ernst Hashagen. The attack took place in the early hours of Friday morning, 14th December. The ship so famous in Dublin, a symbol of hope and solidarity was reported to have been hit forward, and to have gone down within 3 minutes of the time that she started to sink. The attack happened seven miles east of the Kish Lightship. According to the log of U-62, she had been prowling the waters at the entrance of Dublin Bay since just after midnight. A number of potential victims had appeared – “Single ships with all lights blazing, others with only one masthead light or stern light”. There were in fact two torpedoes fired at the S.S. Hare, the first missed. It was as U-62 moved swiftly on the surface towards its prey that it was spotted, but it was too late to react, and a second projectile did not miss, striking the forward hold. The entry in the log is factual and precise – “the ship breaks in two and sinks”. Captain Hashagen gives the order to Submerge and they leave the area.

Captain Carmichael had been below deck in the wash-room when the impact occurred. He was struck in the face by a wash basin, receiving a severe blow to his nose and forehead. Quickly recovering, he rushed on to deck. One of the ships lifeboats was already lowered and full with crew members. Along with five other men he managed to get into a small boat aft, which they launched ‘with some difficulty’.

Tallant would similarly escape the rapidly sinking SS Hare: “When I came to my senses I went down to the lifeboat to get it right. I saw the starboard boat was smashed to smithereens, and the port boat had capsized. I then rushed aft, and sat in a boat there until they floated her. In that boat, beside myself were Captain Carmichael, Wm. McGowan. A.B; Ed. Lyons, greaser; and second engineer Smith. We pulled the bullock-man, John Ford, out of the water. The sea was a bit choppy, and there was a bit of a breeze from the West.”

Five other crew (Richard Daly, greaser; John Hunt, donkeyman; Tom Brown, fireman; Able seamen Patrick Keown and John Conlon) were clinging to the upturned boat nearby. Assistance could not be given, as according to Capt. Carmichael their own boat was ‘half full of water’ and consequently they were ‘unable to render them any assistance, because their boat could hold no more and was in danger of being swamped’.

”We tried to keep as close as possible to the men on the upturned boat. After about 3 hours we were picked up by a steamer, which went round twice looking for the others. The captain of the latter steamer sent a wireless message for assistance. We were well treated by our rescuers”. Their salvation had come at about 5.40am.

“A steamer passing the vicinity of the disaster shortly after the occurrence heard calls from the water. It was pitch dark at the time, and despite the danger the passing boat was hove to and put about, with the result that she picked up one of the Hare’s lifeboats containing six of the crew of the latter vessel”. Another vessel would rescue the other five men at about 10.45 am; almost eight hours after their ordeal had begun. According to a report “the rescued men when first brought aboard were in a state of extreme exhaustion after their terrible experience, and were treated with great care and kindness by the officers and crew of the rescuing ship, to whom they expressed profuse gratitude”.

One of the rescued men, Thomas Brown from Pigeon House Road, gave a vivid description of how he had been in the engine-room at the time of the explosion, and was very badly injured about the legs and body. He somehow made it into the port lifeboat but this did not drop; “The Hare capsizing brought down the boat and all hands”. He swam for sometime before managing to reach the upturned boat, and with his companions would cling on for eight hours. He himself was said to have been unconscious for 3 hours, and had no recollection of subsequent events. On the rescuers who removed them from the sea, he would comment that “the officers treated us most kindly”.

The starboard lifeboat was described as being “smashed to smithereens.” There are conflicting reports about the fate of Stewardess Mrs. Arnott, the only woman crew member. One survivor recalled seeing her on the deck and being assisted to the lifeboat which was subsequently ‘smashed and its occupants drowned’. Another man stated that she did not leave her cabin in the few short minutes been impact and sinking.

An early report noted that “A deck load of Jacobs’s large and empty biscuit skips was floating after the disaster, and some of the crew may have saved their lives by clinging to them”. However, apart from the six men in one boat, and the five who were clinging to the upturned nobody else was rescued.

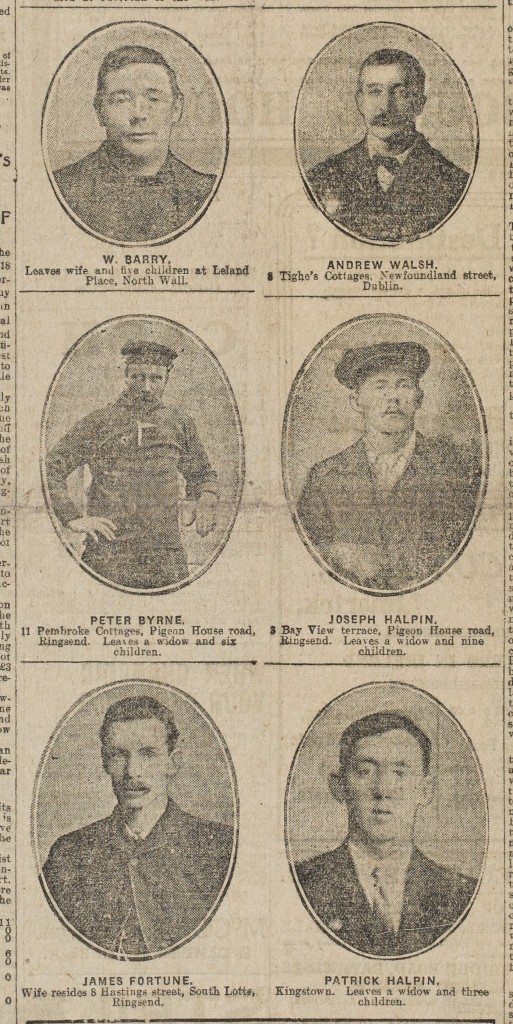

Of the 23 souls who had been on board the SS Hare when it left Manchester destined for North Wall, eleven would survive and twelve would be lost. None of the bodies of the deceased were ever recovered.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” , published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information , corrections , clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

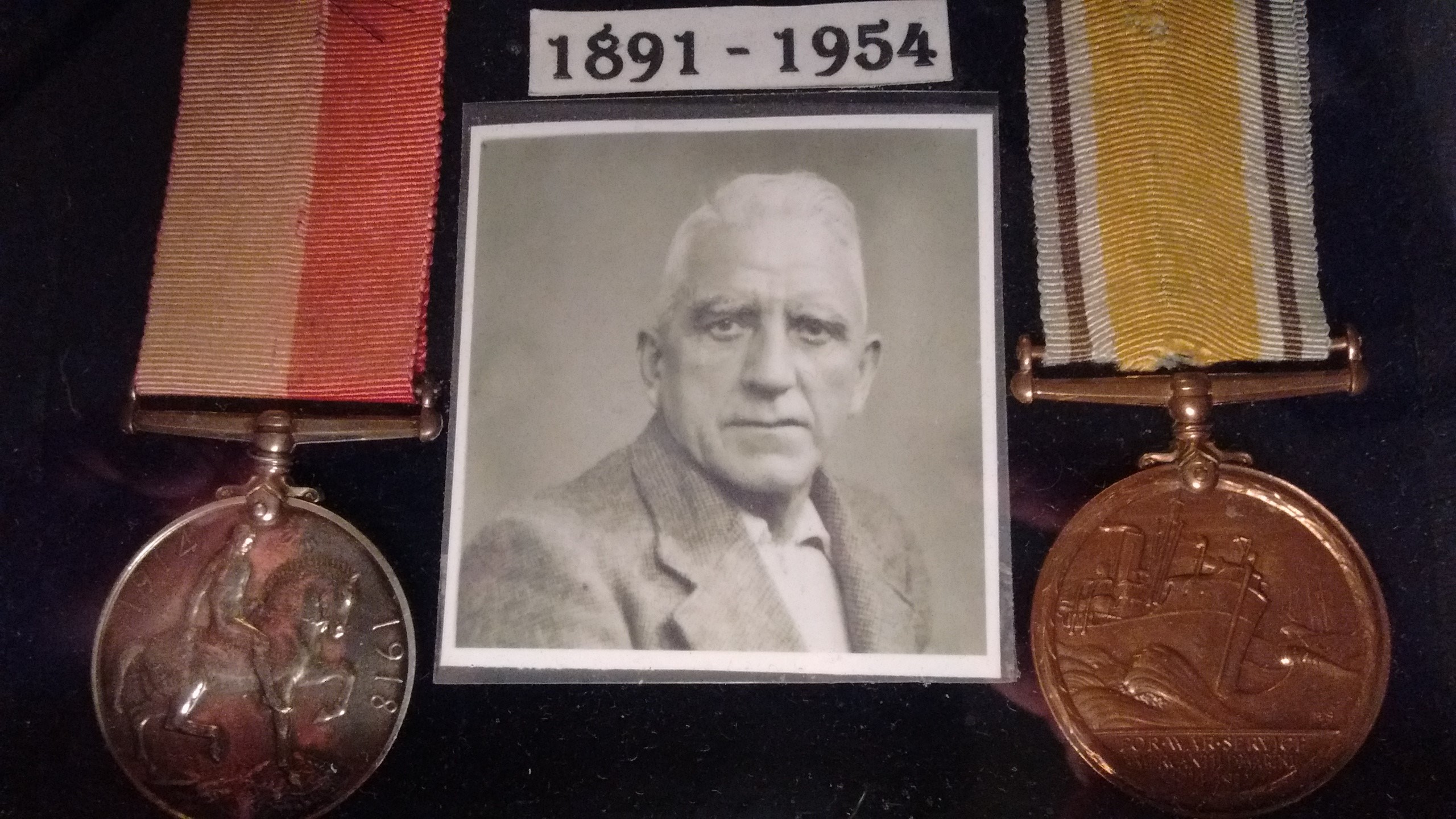

Image credits:

The family of John Conlon

The family of Thomas Brown

Patrick Hugh Lynch

The family of Ernst Hashagen

Dec 10

The SS Hare : A tale of solidarity, hope and stout

The SS Hare was a steamship built in 1886 at Barclay Curle & Co. shipyard in Glasgow for G&J Burns Ltd. In 1899 ownership was transferred to George Lowen of Manchester. In partnership with Dublin business man D.J. Stewart, Lowen had established The Dublin & Manchester Steamship Company In 1897. Stewart was also the owner of the SS Duke of Leinster, from which vessel a number of the crew of the SS Hare transferred. This included Alexander Carmichael, 1st mate on the SS Duke of Leinster, who joined the SS Hare in February of 1900 and the following month became its Captain, a position he would still be holding on the ill fated voyage of 1917. For the years under his command, the SS Hare’s activity was recorded as ‘Trading between Dublin & Manchester carrying General Cargo, Livestock and Passengers”. On occasion trips to Liverpool were also undertaken.

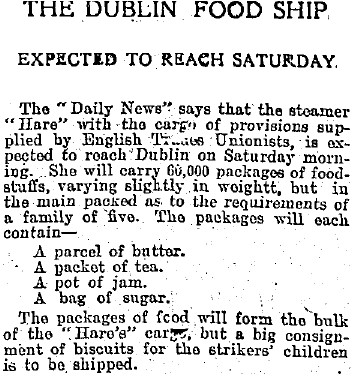

It was during the industrial conflict of the Great Lockout in 1913 that the SS Hare came to fame among the Irish working class. James Larkin had founded the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU) in 1909. He sought to unite Irish workers into one big union and used their numbers to force a radical change not just in the workplace but in society. The Dublin Docks were a prime recruiting ground, and labourers, carters, etc., flocked to its ranks. The ‘Larkinites’ won many key concessions and improvements in pay and conditions, the use of the sympathetic strike being a powerful tactic. Fearing the growth of organised labour, powerful businessman and newspaper owner William Martin Murphy, formed the Dublin Employers Federation. Workers were urged to sign a declaration disassociating themselves from the ITGWU. When many refused they were ‘locked out’ of their employment. The dispute escalated and soon 20,000 workers were involved, and in an already poverty stricken city this was catastrophic. Murphy believed that the workers could literally be starved into submission, informing the Dublin Chamber of Commerce:“The employer all the time managed to get his three meals a day, but the unfortunate workman and his family had no resources whatever except submission, and that was what occurred in 99 cases out of 100. The difficulty of teaching that lesson to the workmen was extraordinary.”

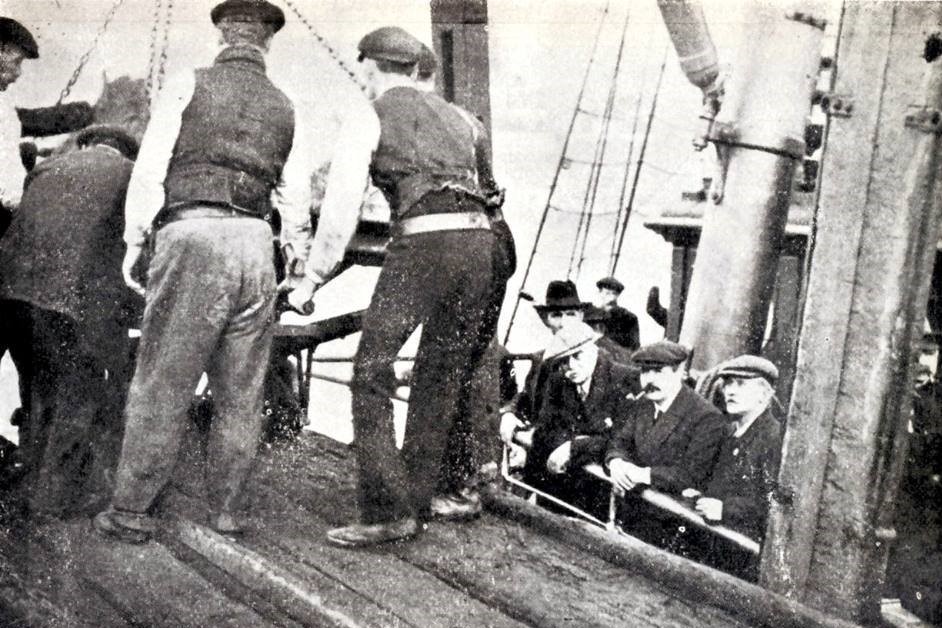

Larkin travelled to Britain to rally support, and the response from the workers there was phenomenal. The British Trade Union Congress (T.U.C.) raised funds to send essential supplies to their Dublin comrades, and an initial shipment of 60,000 food parcels was dispatched.The SS Hare was actually strike bound with a cargo of Guinness onboard, but agreement was reached to unload the cargo and she soon set off across the channel. The SS Hare sailed into Dublin on 27th September 1913 to scenes of jubilation. Paddy Buttner, a young boy at that time, was there to collect food for his family, his father being one of the strikers. He recalled the excitement –

“…a cheer rose from every throat of those watching when someone cried ‘It’s the SS Hare!’ The captain answered the swell of cheering with three sharp and one long blast on the siren , and it seemed to me , just a boy , to be saying – ‘It’s US, it’s US, it’s US ,HURRAY!’ The hair stood up on my head and I shouted with the rest in joy. As the vessel came abreast of the South Point, we all turned about and kept pace with her; the cheering and the waving continued while tears streamed down the faces of women and, indeed, men too. And all the while the crew and siren answered each cheer”.

This voyage of hope was only the first undertaken by the SS Hare, and she would be joined by the SS Pioneer and SS New Fraternity.The goods were stored in the Manchester Shed on Sir John Rogerson’s Quay throughout the Lockout. Thanks to the efforts of the T.U.C. by late November 255,330 packets of tea had been shipped to Dublin, 255,000 bags of sugar, 255,330 packets of margarine, 597,000 loaves of bread, 251,804 bags of potatoes, 1,856 lb of Jacob’s Biscuits, 72,639 pots of jam, 85,330 tins of fish, 12,500 boxes of cheese and almost 885 tons of coal. Food parcels were distributed right up until February of the following year when the strike was ended. This act of solidarity literally saved lives in Dublin, and has never been forgotten.

The 1913 log concludes “Ship lying in Dublin through Labour strike from Nov.12thuntil end of year”

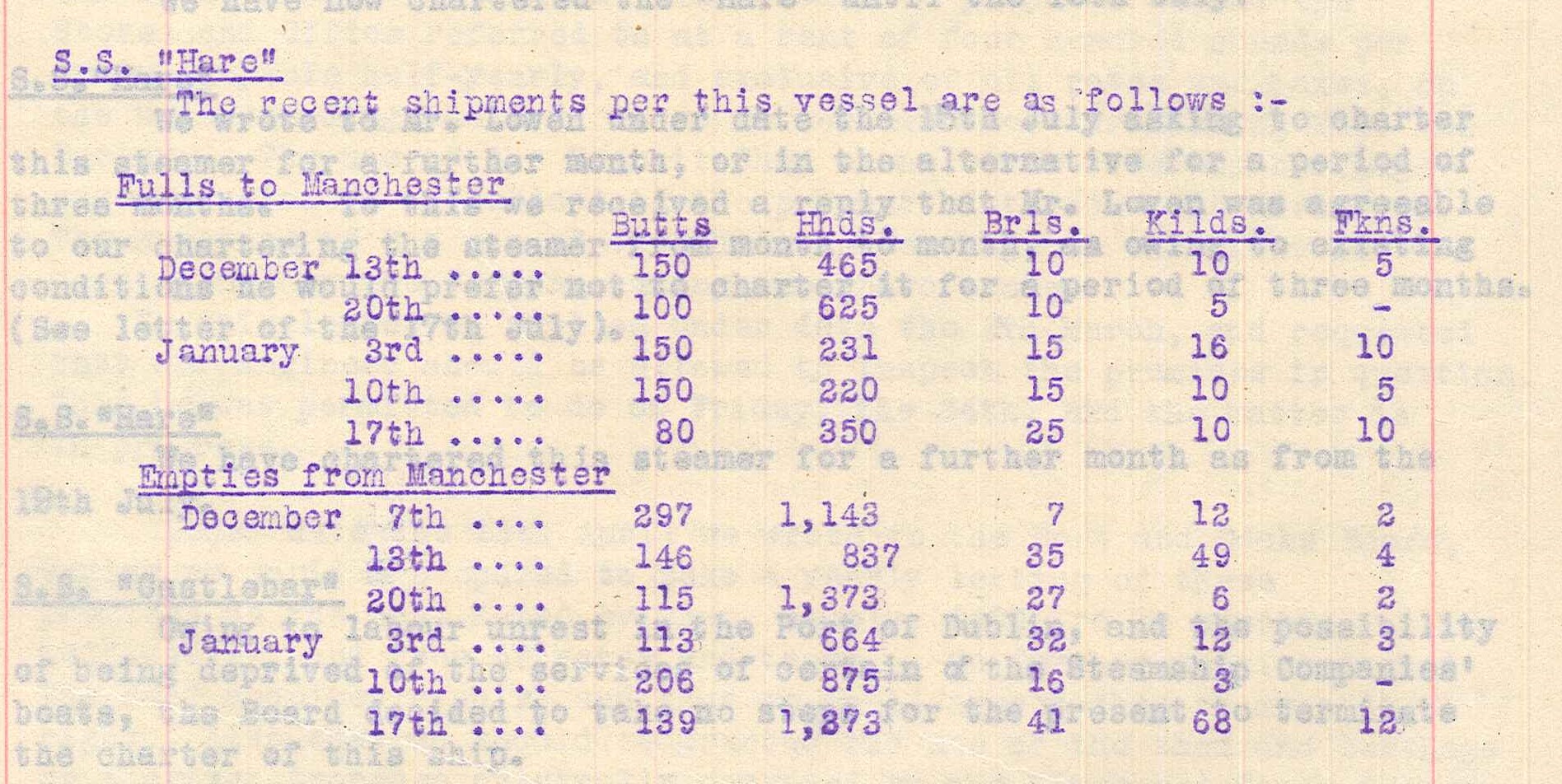

The SS Hare would carry a variety of cargo in its lifetime, but it’s most famous customer was undoubtedly the Arthur Guinness, Son & Co. LTD. The iconic brewery would begin to develop their own legendary ‘Guinness fleet’ at the end of 1913, but the SS Hare would continue charters with the company until its loss. The regular routine would see barrels of stout being delivered to Manchester and the empty casks returned to Dublin.

As stated, the SS Hare was carrying a cargo for Guinness when it made its memorable Lockout mission. Communications from Guinness show that they expected nothing less than being accommodated-“I was fully aware of the circumstances under which she had been discharged”, but further added “under our agreement we were bound, while the boats were sailing, to give him our traffic and they were equally bound to take it.”

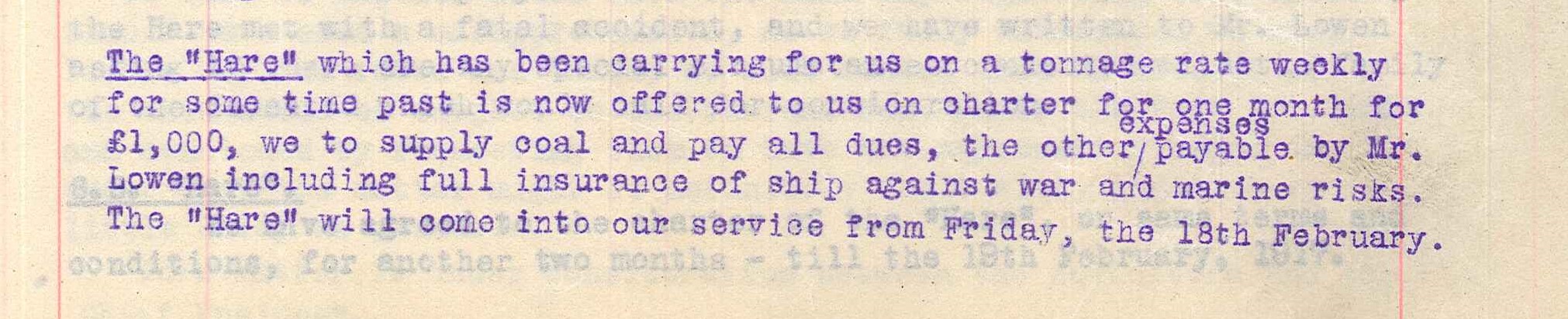

Throughout 1916 there was a series of agreements which essentially saw the SS Hare being on permanent contract during that historic year. Having enjoyed a series of weekly arrangements, inFebruary the Brewers accepted a “charter for one month for £1,000, we to supply coal and pay all dues, the other expenses payable to Mr.Lowen including full insurance of ship against war and maritime risks”.For the first half of April the Ship was in Dock for repairs but re-entered service just before the Easter Rising. Shipping from Dublin was curtailed during the rebellion, but on 3rd May the SS Hare arrived in Manchester with a cargo of Guinness, the first Dublin Port vessel to dock across the channel. There was a request from Guinness to charter on a three monthly basis but George Lowen was not agreeable. Lowen preferred a month-to-month arrangement, but eventually they settled on a two monthly arrangement.

Guinness of course had built up its own fleet by now. War time restrictions on brewing imposed by the Governmentled to a reduction in the demand for cross-channel cargos and the arrangements with Lowen concluded at the end of May. However, in June the Admiralty commandeered the SS Clarecastle and SS Clareisland from the Guinness fleet, forcing the Company to request the return of the SS Hare. They were informed that the vessel was not available due to other engagements.

During this period Guinness was experiencing real difficulties in shipping its product to a variety of destinations. They entered discussions with Tedcastle’s to arrange for 100 tons of stout to be carried to Liverpool on a weekly basis, though if this was to be on board the SS Adela is unclear.

On the 12th October 1917, the first of the Guinness fleet, the SS W.M. Barkley was torpedoed crossing the Irish channel. Almost exactly two months later when the SS Hare was lost in a similar attack at almost the same location. Of the 23 crew on board twelve would lose their lives while 11 would survive.

Following the sinking of the SS Hare, Guinness noted the loss as follows:

“This boat, which carried our beer for many years between Dublin and Manchester, and was frequently chartered by us, was torpedoed on Friday, the 14th, in the same locality as our own steamer the Barkley. She carried none of our property on this voyage. Eleven of her crew of twenty-two, including the Captain and the Chief Engineer, were saved”.

There is a final reference to the SS Hare recorded in Guinness reports, dated 25thJanuary 1918:“Lord Iveagh was reminded that we had written to Mr. Lowen telling him we were willing to assist in giving any financial assistance granted to the relatives of those who were lost in the HARE, but we’ve since heard from Mr. Lowen stating that he considered the public arrangements were ample to meet the necessities of the case, and that it was not proposed to take any steps in the matter.”

That was their last word on the relationship between the City’s most iconic product and one of the most famous vessels in the history of Dublin Port.

Eleven of those who were serving on the SS Hare in 1913 were aboard on the fateful voyage of December 1917. Daniel Eley, Donald Gilchrist, Lachlan MacFadyen, Joseph Edward Swords, Charles Walsh, James Wilson would lose their lives,while Alexander Carmichael, Thomas Brown, John Hunt, William McGowan and Christopher Tallant would survive.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” , published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information , corrections , clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

Image credits: ‘Guinness Archive, Diageo Ireland’

SS Hare painting by Kenneth King , courtesy of Eric Hopkins who commissioned the work.