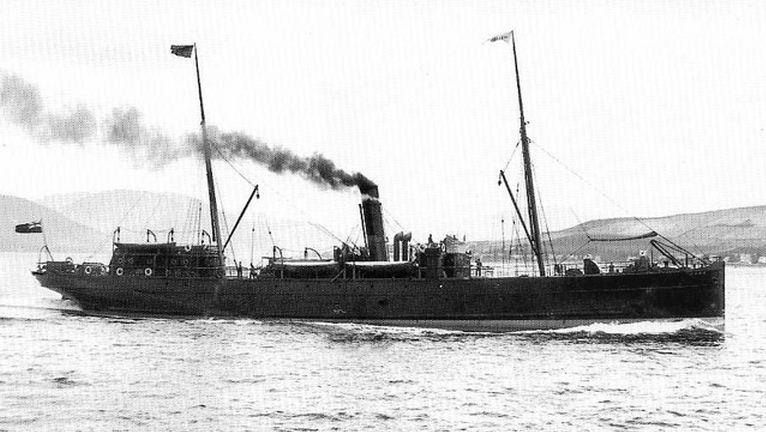

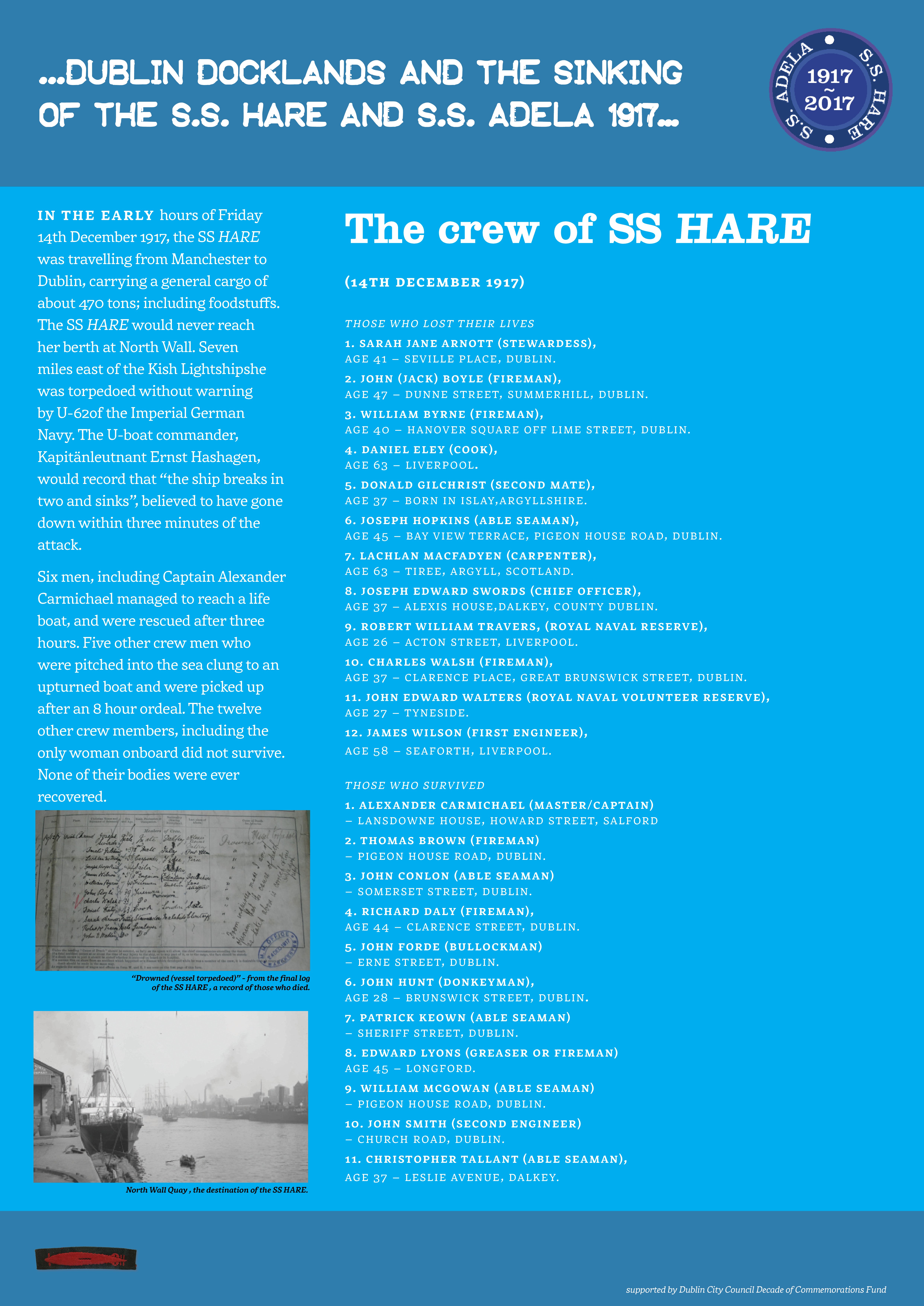

The SS Hare set sail from Manchester to make the journey to Dublin on the evening of Thursday 13th December 1917. It was a familiar route for the steamer, one it had regularly travelled over the previous two decades, with many of the crew being old hands onboard. She was carrying a general cargo of about 470 tons, including foodstuffs. As a British Merchant Navy ship, it carried light armaments for protection. Accordingly there were two Gunners, of the Royal Naval Reserve, in addition to the ship’s crew. There were no additional passengers on board.

As the ship approached Dublin, 1st Officer Joseph Swords and Able Seaman Christopher Tallant were on the bridge. AB Tallant survived the catastrophe that was about to unfold, and would recount the final moments before the ship was struck: He had spotted a vessel which appeared about 100 yards aft. The chief officer went to the starboard side with the glasses, and had a look at her.”She is travelling fast” was all Joseph Swords had time to say, before the impact. Tallant was ‘knocked senseless from the wheel’ and ‘saw the chief officer no more’. The SS Hare had been torpedoed without warning by the submarine U62 of the Imperial German Navy, under the command of Kapitan Lieutenant Ernst Hashagen. The attack took place in the early hours of Friday morning, 14th December. The ship so famous in Dublin, a symbol of hope and solidarity was reported to have been hit forward, and to have gone down within 3 minutes of the time that she started to sink. The attack happened seven miles east of the Kish Lightship. According to the log of U-62, she had been prowling the waters at the entrance of Dublin Bay since just after midnight. A number of potential victims had appeared – “Single ships with all lights blazing, others with only one masthead light or stern light”. There were in fact two torpedoes fired at the S.S. Hare, the first missed. It was as U-62 moved swiftly on the surface towards its prey that it was spotted, but it was too late to react, and a second projectile did not miss, striking the forward hold. The entry in the log is factual and precise – “the ship breaks in two and sinks”. Captain Hashagen gives the order to Submerge and they leave the area.

Captain Carmichael had been below deck in the wash-room when the impact occurred. He was struck in the face by a wash basin, receiving a severe blow to his nose and forehead. Quickly recovering, he rushed on to deck. One of the ships lifeboats was already lowered and full with crew members. Along with five other men he managed to get into a small boat aft, which they launched ‘with some difficulty’.

Tallant would similarly escape the rapidly sinking SS Hare: “When I came to my senses I went down to the lifeboat to get it right. I saw the starboard boat was smashed to smithereens, and the port boat had capsized. I then rushed aft, and sat in a boat there until they floated her. In that boat, beside myself were Captain Carmichael, Wm. McGowan. A.B; Ed. Lyons, greaser; and second engineer Smith. We pulled the bullock-man, John Ford, out of the water. The sea was a bit choppy, and there was a bit of a breeze from the West.”

Five other crew (Richard Daly, greaser; John Hunt, donkeyman; Tom Brown, fireman; Able seamen Patrick Keown and John Conlon) were clinging to the upturned boat nearby. Assistance could not be given, as according to Capt. Carmichael their own boat was ‘half full of water’ and consequently they were ‘unable to render them any assistance, because their boat could hold no more and was in danger of being swamped’.

”We tried to keep as close as possible to the men on the upturned boat. After about 3 hours we were picked up by a steamer, which went round twice looking for the others. The captain of the latter steamer sent a wireless message for assistance. We were well treated by our rescuers”. Their salvation had come at about 5.40am.

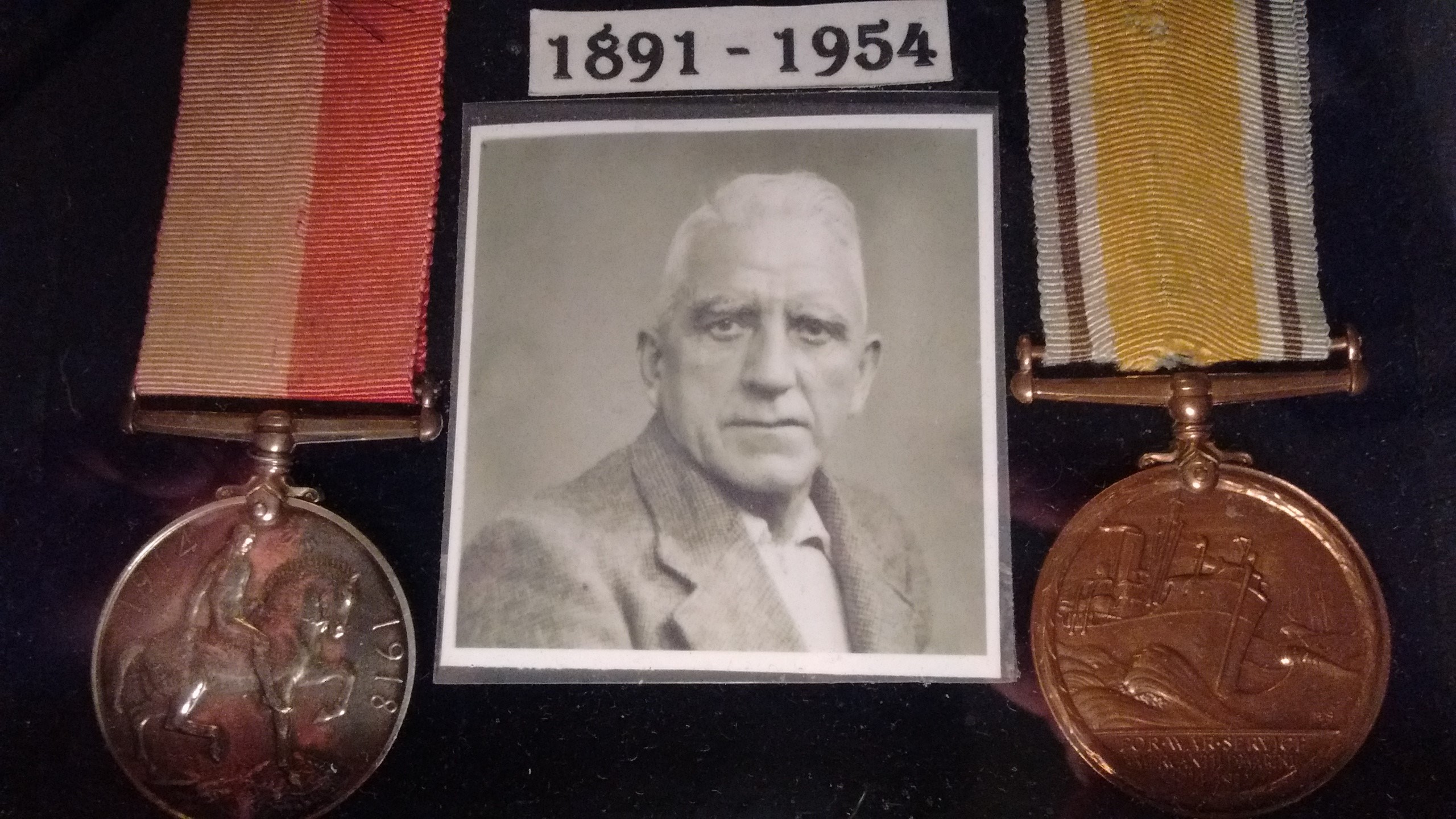

“A steamer passing the vicinity of the disaster shortly after the occurrence heard calls from the water. It was pitch dark at the time, and despite the danger the passing boat was hove to and put about, with the result that she picked up one of the Hare’s lifeboats containing six of the crew of the latter vessel”. Another vessel would rescue the other five men at about 10.45 am; almost eight hours after their ordeal had begun. According to a report “the rescued men when first brought aboard were in a state of extreme exhaustion after their terrible experience, and were treated with great care and kindness by the officers and crew of the rescuing ship, to whom they expressed profuse gratitude”.

One of the rescued men, Thomas Brown from Pigeon House Road, gave a vivid description of how he had been in the engine-room at the time of the explosion, and was very badly injured about the legs and body. He somehow made it into the port lifeboat but this did not drop; “The Hare capsizing brought down the boat and all hands”. He swam for sometime before managing to reach the upturned boat, and with his companions would cling on for eight hours. He himself was said to have been unconscious for 3 hours, and had no recollection of subsequent events. On the rescuers who removed them from the sea, he would comment that “the officers treated us most kindly”.

The starboard lifeboat was described as being “smashed to smithereens.” There are conflicting reports about the fate of Stewardess Mrs. Arnott, the only woman crew member. One survivor recalled seeing her on the deck and being assisted to the lifeboat which was subsequently ‘smashed and its occupants drowned’. Another man stated that she did not leave her cabin in the few short minutes been impact and sinking.

An early report noted that “A deck load of Jacobs’s large and empty biscuit skips was floating after the disaster, and some of the crew may have saved their lives by clinging to them”. However, apart from the six men in one boat, and the five who were clinging to the upturned nobody else was rescued.

Of the 23 souls who had been on board the SS Hare when it left Manchester destined for North Wall, eleven would survive and twelve would be lost. None of the bodies of the deceased were ever recovered.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” , published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information , corrections , clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com

Image credits:

The family of John Conlon

The family of Thomas Brown

Patrick Hugh Lynch

The family of Ernst Hashagen