WW1 SUBMARINE VICTIMS : HELP FOR DEPENDENTS IN DUBLIN

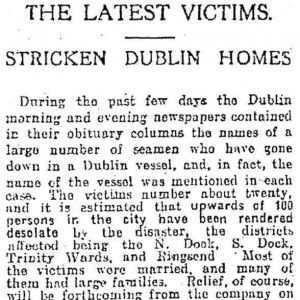

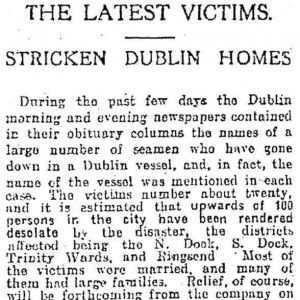

“It has been estimated that upwards of 100 persons in the city have been rendered desolate by the disaster”

On the 14th December 1917 the SS Hare was torpedoed as traveled from Manchester to Dublin Port , with the loss of 12 lives. Just a fortnight later the SS Adela was similarly targeted as it traveled from Dublin to Liverpool , with the loss of 24 lives. As the New Year of 1918 got underway , the population of Dublin City rallied around to support the families of those who had died.

Due to war-time censorship the initial press reports did not name the vessels or refer to U-boats as the cause of the ‘tragedy’ or ‘loss’. In the closely knit Dockland and seafaring community they knew. The effect of the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela was seismic, with the ripples quickly spreading through the business community of the city. From the start of the war deaths of Docklands dwellers in far off places such as Gallipoli, the Somme, and Passchendaele had been regular, and it was not uncommon for ships to fall victim off the Irish coast. 159 ships were sunk in Irish coastal waters during 1917. However, the majority of these were sunk off the Atlantic coast, and though the Irish channel had become increasingly hostile, these Christmas season attacks brought home the reality of war like never before. The impact can be seen in the tremendous support effort in the aftermath, where literally the whole population played a role, from the richest business owners to the poorest quay side labourers, from those who built the ships to those who sailed them, from trade union leaders to captains of industry, and crossing all religious and political divides.

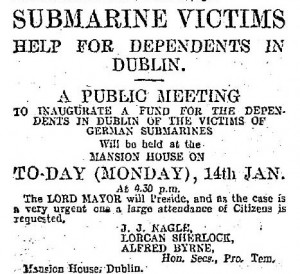

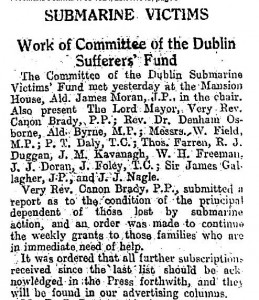

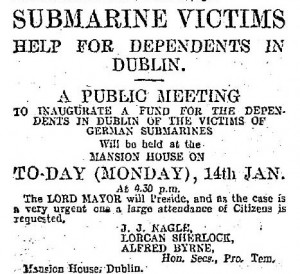

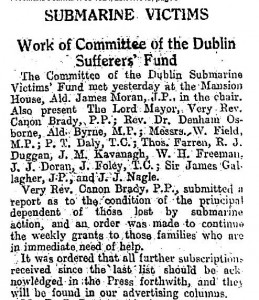

In early January several influential politicians, trade unionists, and businessmen met at the Mansion House to set up a Submarine Victim’s Fund for the dependents of those lost at sea. A public meeting was held three days later and over the next six months substantial funds were raised. Although not complete, from the published lists we can get some sense of the reality check which hit, as the community began to realise that nobody was safe even on the short trips across the Irish Sea.

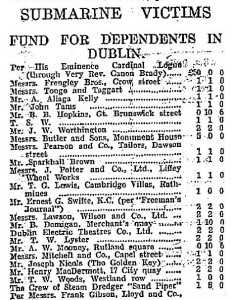

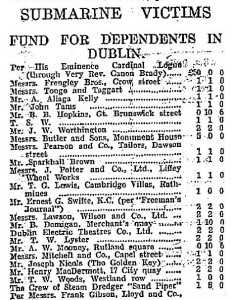

Among the first individual donors was Walter Scott of the Dublin Dockyard Company. Irish Shipbuilding was booming during the war, led by Belfast’s Harland and Wolfe. That city’s “wee yard” at Workman Clarke was setting world records in building a new simplified transport craft to replace the numerous ships being sunk each month. The smaller Dublin Dockyard Company was struggling to meet orders due to a shortage of space and lack of skilled men. This was so serious that a blind eye was being turned to former staff who had fought in the 1916 Rising as craftsmen were in such short supply. The Company itself gave £100 while the workforce, dividing along their trade union lines each gave individual donations amounting to over £50.

Local dockland based companies, reliant on ships for exports and imports, made donations –Barrington’s Soap Factory on Sheriff Street, Ross & Wallpole Iron Founders, The Dublin Glass Bottle Company, Boland’s Bakery, T. & C. Martin, Timber Merchants, Cherry & Smaldridge Printers, on Seville Place, Goulding’s Fertilizer Company, Smith & Pearson, British Petroleum (originally a German Registered Company) and many others.

Municipal employees were generous-Dublin Corporation Main Drainage workers at the Pigeon House Fort donated as did their colleagues at the Pigeon House Pump Station, and the adjacent Electrical Power Station. So too did those at the Pump Stations on East Road and Forbes Street.

Those engaged in transport, both seafaring and dockside, were affected, and most would have known the victims and their families. The Dublin Steam Trawler Company donated as did the Captains and crews of the SS Carlow, SS Belfast, and SS Yarrow. Many of their crew members had previously served on both the Adela and Hare. The crew of the Corporation dredger SS Shamrock gave funds as did the Irish Ships Firemen’s Trade Union and the Irish Stationary Engine Drivers Union, which represented crane-men on the docks. Dublin Port’s Harbour Master, John Henry Webb, and his assistant James Brady contributed (as did Brady’s brother, the MP for St.Stephen’s Green, Patrick Joseph Brady). The workers club of the Midlands Great Western Railway also supported the cause along with many other businesses and workforces North and South of the Liffey. Hauliers such as Wallis and Pickfords also appear on the lists. Most of these workers were earning war bonuses and there was no shortage of work. With the sinking of these well-known vessels, the reason for this became only too apparent.

Entertainment and sporting bodies were called upon to support these efforts and responded magnificently. The Queen’s Theatre performed a matinee of their successful pantomime, Tom Thumb, which raised £48. The Royal Theatre then staged a benefit night which brought in £272.Whippet races were organized at Shelbourne Park raising £66; The Leinster Football Association granted permission for fundraising matches to be played in March and April; Gold Clubs organized dances, bands played concerts, Picture Houses such as the Rotunda, Camden, and Phoenix Picture Palace all donated takings, and in June, the Committee in charge of the Irish Derby Sweep, run at Baldoyle, announced that they were donating £1400 to the cause.

In the wider business community donations were received from many of the leading departments stores and business such as Arnotts, Switzers, Findlaters, the Varian Brush Company, Dockrell’s, Pimm’s Department Stores, individual donations from each of the Eason brothers, and many more besides. Jameson’s and Power’s Distillers, The Mountjoy Brewery, and Guinness (all involved in exporting their products) were not found wanting. Guinness coopers made a separate donation. The Car Company Ashenhurst Williams and the Iron Founders Thompsons (both engaged in wartime manufacturing), are also on the list. Hopkins and Hopkins Jewellers, The Irish Times, even William Martin Murphy of Independent Newspapers all donated as did hundreds of individuals from all over Ireland and Britain.

The response crossed the religious divide. Canon Brady of St Laurence O’Tooles parish was one of the originators of the fund, with many of the victims and their dependents coming from his parish. His Co-organiser, Rev. Dr. Denham Osbourne of Rutland Square Presbyterian Church received numerous donations from amongst his co-religionists, while many parishioners from the three main religions contributed through their Parish Priest, Rector, or Minister. The Irish Jewish Association made a generous donation and then over 50 individual Jewish Businessmen also contributed.

The largest business contribution came in January from the Irish Cattle Traders and Stockowners Association and amounted to £1,100. Michael Cuddy of their Committee was from Seville Place and an extensive exporter of cattle and sheep. Cuddy’s family had a Butchers Shop at Spencer Dock Bridge, and it’s likely that he knew many of those that died and their families, having employed them at one time. Both the SS Adela and SS Hare had cattle drovers among their crew. The sinking of the RMS Leinster in October 1918 has historically overshadowed the loss of the Adela and the Hare. However, from the subscription lists we can see how far reaching the consequences were after the sinking of the latter two ships. Both ships were sailing in what should have been safe waters. Now all was changed and the reality of it would reverberate not just through the victim’s relatives but right through the entire population of Dublin and beyond.

This article appears in “Within the seat of war …Dublin Docklands and the sinking of the SS Hare and SS Adela 1917…” , published by The Adela-Hare Centenary Commemoration Committee , September 2017. Supported by Dublin City Council Decade of Commemoration Fund.

For further information , corrections , clarifications or to obtain the book contact adelahare1917@gmail.com