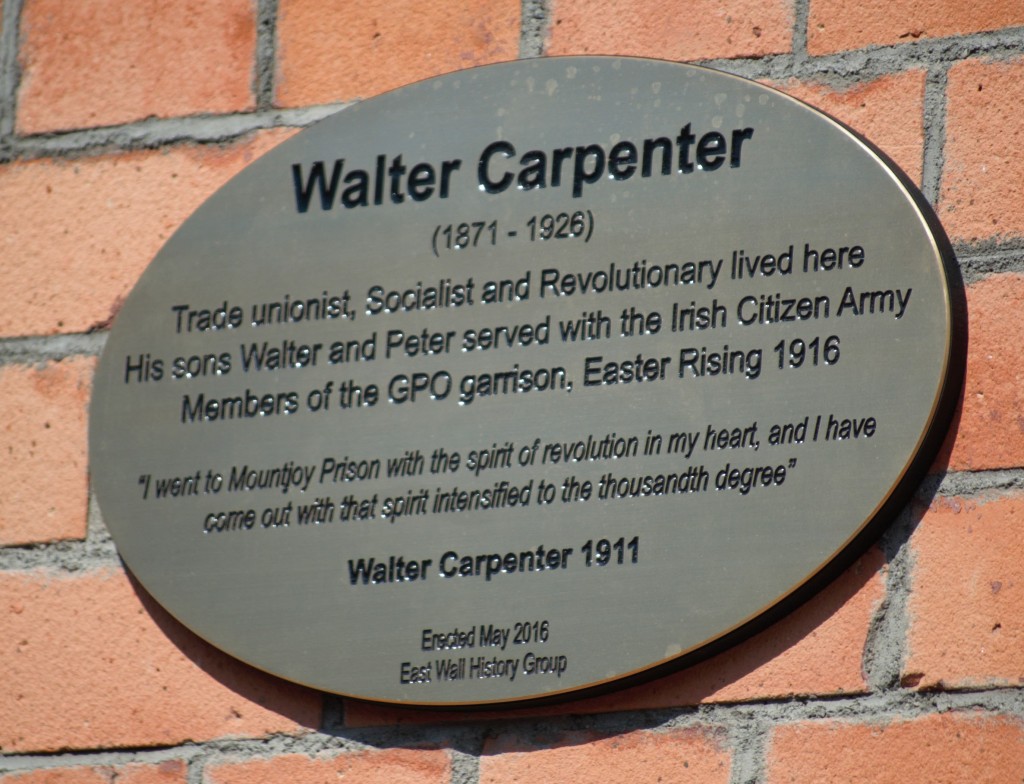

Last year the East Wall History Group marked the 90th anniversary of the death of Walter Carpenter by erecting a plaque on the former family home on Caledon Road and launching an excellent book written by his Grand Daughter Ellen Galvin. To mark his anniversary this year , we are presenting this piece by D.R.O’Connor Lysaght (of the Irish Labour History Society) which looks at Carpenters role within the Communist movement . While this can be enjoyed as a stand-alone article , it is best read as an accompaniment to “Walter Carpenter : A Revolutionary Life” .

WALTER CARPENTER: AN ADDENDUM by D.R.O’Connor Lysaght.

Introduction.

Dr. Ellen Galvin has made a valuable contribution to Irish labour

history with her life of her grandfather, Walter Carpenter. It is now

possible to use this one pamphlet to get a reasonable idea of his

career in the working class movement.

Though the Foreword prophesies that ‘there is no doubt that material

relating to Walter’s political activity will continue to materialise’,

there is little to be added to what is presented here save in one

aspect. Dr. Galvin mentions ‘a period of time when Walter was heavily

occupied in trying to build the Communist Party and continue the

promotion of a more radical overhaul of society.’ Then she moves

quickly to his declaration on his resignation as secretary of that

party, without mentioning the fact that he had been the first to hold

that post.

Walter Carpenter’s role in the Communist Party (CPI) was the result of

considerably more than what Yeats termed ‘ignorant good will.’ The

party’s establishment had been achieved after a major struggle with

the leaders of the Labour Party and TUC, including his old comrade

from their Socialist Party days, the formidable William O’Brien.

Moreover, as a Communist he took positions on the strategic issues

affecting the labour movement in its quest for power. It is

understandable that debates on these matters should be ignored here;

they appear to be of less obvious importance than the practical causes

to which Walter gave his time. Nonetheless, his political development

after 1916 was obviously relevant to him but also to labour as a

whole then and today.

Walter Carpenter, Communist.

When Walter Carpenter joined the Socialist Party of Ireland he was

joining an organisation that accepted a basic Marxist analysis of

society, much of which had been developed for Irish conditions by

James Connolly. The party’s theory involved the materialist

interpretation of history, the labour theory of value and a generally

revolutionary political perspective. Connolly had included in the

first the view that capitalism itself was foreign to the Irish and, in

the third that therefore, organically, rather than potentially, the

cause of Ireland was the cause of labour and that, accordingly, in the

third aspect, there was no need of a party of conscious professional

socialists as in the rest of Europe (most successfully in Russia) to

lead the workers to their republic; the industrially organized working

people would accomplish this themselves in a struggle that could arise

from an oppressed people’s fight for self-determination.

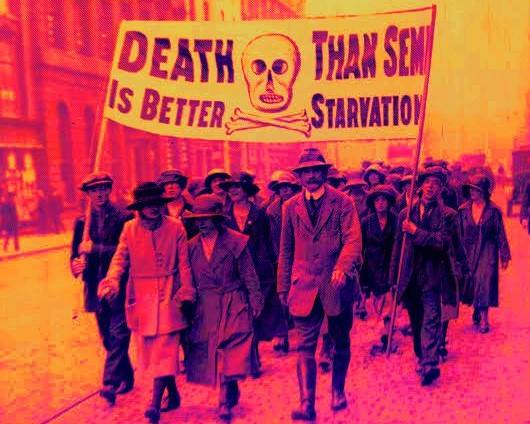

The Easter Rising and its aftermath caused much rethinking among Irish socialists. The ITUC Chairman, Thomas Johnson gained support for a strategy that revised Connolly; he separated the national and the

social struggles. The first was to be left to the nationalists, save

in cases of obvious undemocratic abuse. Meanwhile, Irish Labour was to expand its organisation (nearly 50% of which was then in Dublin) and

preach obviously practical socialist demands to prepare for the time

when Ireland would be free and it could challenge the nationalists for government power. Whether the nationalists would be able to establish an independent Irish state or whether any state they did establish would not be itself a barrier to the workers forming their own republic was not questioned.

As Dr. Galvin shows, the Carpenter family had followed Connolly’s approach to the overall national and social struggles far more loyally than many who supported Johnson. Walter and his sons had been in the Citizen Army and young Walter and Peter had fought in the GPO. Defeat caused Walter to reconsider and he, too, backed the Johnson line. He justified his position in his first speech to a conference of the Labour Party and TUC where the possibility of fighting the 1918 general election was being discussed:

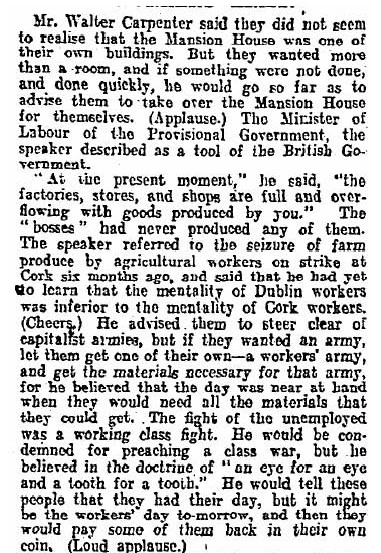

‘He, for one, did not believe that the working classes of Ireland educated enough to justify the Executive in running candidates.’ (Irish Labour Party & TUC, Annual Report 1918 (Special Conference at Mansion House, Dublin, 1-2 November 1918), P.108.)

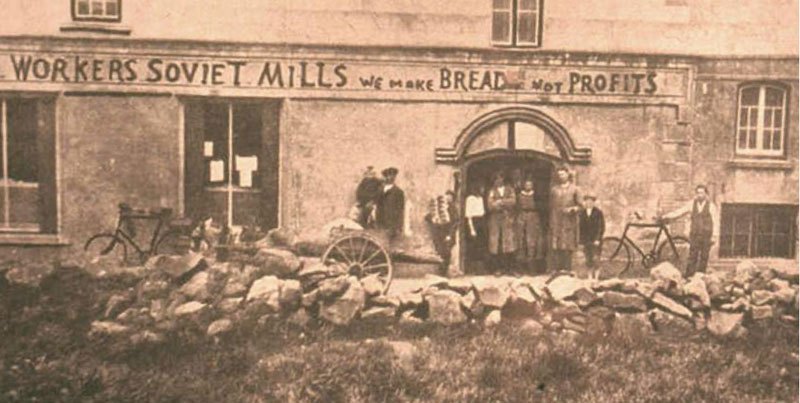

Even then, there was a difference between the Labour leadership and Walter Carpenter. While internationally, they were at one in hailing the October revolution in Russia, Carpenter saw possibilities in it that the others could or would not. On the same day as the speech quoted, the Labour paper, Irish Opinion/The Voice of Labour, reported that he had agreed on behalf of his union, the International Union of Tailors to organize his locked-out members in what he styled a soviet concern manufacturing garments from the union’s York Street headquarters to supply retailers. A fortnight later, the paper reported it supplying ‘the most important houses in Henry Street’ but to be plagued by problems of lighting and heating. The same paper, on 18 January, claimed the soviet was being victimised by hostile colonial government inspectors, a problem arising from the weakness of workers’ co-operation against a capitalist state. Indeed, the split in that state’s power seems to have helped the tailors; on 19 July, the paper reported the soviet expanded to second premises at 59 Middle Abbey Street.

To the Labour leaders, the tailors did not pose a threat, ‘soviet’ or no. They were far more worried by attempts to create a labour vanguard of the Bolshevik type as attempted by Sean O’Hagan and Selma Sigerson in Belfast and supported by Sean MacLoughlin in Dublin. Organisationally, Walter Carpenter expected little from political action and remained loyal to what would prove to be the reformist majority. At the Labour Party & TUC Annual Meeting in August 1919, he defended that majority’s liquidation of the Limerick Soviet:

‘The whole discussion had been a vindication of the action of the Executive. The National Executive could not have taken any other action than what they (sic) did, and he said that as one who was an advocate of the general strike. He knew what the general strike meant – that it has got to be backed up by guns, that it meant a revolution; and until they were prepared for revolution there was no use calling a general strike. Unless they were prepared to use the guns and hoist the Red Flag from one end of the country to the other, there was no use in condemning the National Executive because they did not call a general strike. The workers were not class conscious enough, not educated enough, and not ready for a general strike. When the day came that they were class conscious and educated the workers would not want leaders – they would go out themselves. He could listen no longer to members of the Executive being abused. Limerick itself had declared emphatically that it was not let down. He hoped the day would soon come when they would be ready for the general strike, when they would be able to put in practice in Ireland what they had done in Limerick and establish a soviet republic.’ (Applause) – (Irish Labour Party and TUC,Annual Report 1919, P.80.)

This might be considered to be a typical left cover for a commitment to defeat, were it not for other events. Two months previously, Sean MacLoughlin had called for the Socialist Party of Ireland to convert itself from a propaganda group into a ‘Workers’ Republican Party’ in the Bolshevik style. The next month, he became its Chairman of Propaganda. On 16 December, at a special Labour conference, Carpenter moved a proposal to extend a motor drivers’ strike against the carriage of British Army goods to all carriers of such; it was lost 41 to 10.

This defeat was interpreted by the Communists as a sign that they were going too quickly. The SPI had nominated Carpenter and McLoughlin to contest the Dublin municipal elections. In the event only Carpenter ran, and he was defeated. This reduced their radicalism further.

They remained Communists and showed this at the Labour Party and TUC Annual Meeting in August. The National Executive Report urged non-affiliation to either the Third International (Comintern) or to the projected revived Second (social democratic) International, on the grounds of its uncertainty as to their politics. Carpenter and Eamonn Rooney of Drogheda moved the passage be referred back. Carpenter justified the motion by showing that the previous year’s social democratic conference at Berne had refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Workers’ Republics supported by the Comintern. Thomas Johnson stated that the Executive had refused to affiliate to either International because it disagreed with the politics of both (how, he did not say). Carpenter’s motion was defeated 97-54.

For the next year, class struggle was overshadowed by two factors, the escalation of Britain’s ‘Tan Offensive and the collapse of the post-war boom. The first of these was opposed by Labour through a railway strike against the British carriage of munitions. This had to end in December, but for workers in employment the defeat for their class had its results cushioned by the ending of the boom, the resulting fall in prices and the rise in real wages giving most of them, outside divided Ulster, the largest incomes they had ever enjoyed. This was threatened by the spread of unemployment, to which Labour replied by a manifesto ‘The Country in Danger.’As unemployment was increased by the British forces’ scorched earth policy, the truce with Britain in July 1921 was welcomed for that reason as well as heralding the end of the national struggle and its supersession by that of internal class forces.

At the Labour Party Meeting in August, Carpenter spoke several times expressing his view that the workers should educate themselves by working their industries for themselves. His speech on the railways has been quoted by Dr Galvin. He spoke also on co-operative societies and on land nationalisation. On the first, he warned against ‘a number of alleged co-operative societies that were scattered around the country run by the IAOS [Irish Agricultural Organisation Society – DRO’CL]. To his mind they were not co-operative societies and he would urge the delegates there that instead of trying to get in, because they would never get in, the farmers would never let them. Instead of wasting efforts trying to get into such a society they should form societies of their own….. ‘The moment the idea of dividends entered into the co-operative society it ceased to be a co-operative society at once….’ - Irish Labour Party and TUC, Annual Report 1921, P. 177.

On the need for Labour to win the small farmers, he referred to Davitt’s aim of land nationalisation:

‘It should be stated definitely that the peasant proprietor today, if he were going to be relieved of rent and all the rest of it until his family had a decent standard of living, that he was only holding that land in trust for the people of Ireland, to work for them as well as himself, and that his heirs and successors had no claim on the land when he ceased to exist.’ – Ibid, P.183.

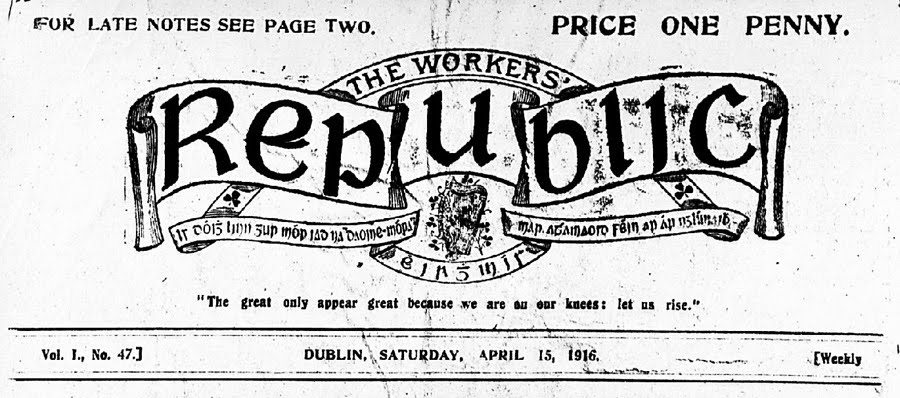

There was no debate on international affiliations. Whether such a discussion had been ruled out of order is unknown. What seems certain is that Carpenter and his comrades considered that as the bosses were trying to force down wages, the time was ripe to counterattack and go ahead with the long delayed Communist Party of Ireland. On 8 October, they presented their manifesto, ‘Workers and Toilers of Ireland’.It announced that the SPI ‘has broken with the old and useless methods of Reformism and takes up once more the revolutionary traditions of its great predecessor the “Socialist Republican Party.” It pledged the party to adhere to the Comintern. On the 14th, it expelled Bill O’Brien and CathalO”Shannon for Reformism and ‘consecutive non-attendance at the Party, and consistent attempts to render futile all attempts to build up a Communist Party of Ireland’. On 5 November, the new party paper, the Workers’ Republic, announced that the SPI had become that party.

But what was it to do? It called for a National Council of the Unemployed and defended strikers, but, beyond this, its most definite plan was that of Roderick Connolly, essentially to withdraw from struggle to raise consciousness. This was altered after 6 December, with the publication of the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty with Britain. The party recognized that this was where political reaction would secure state power for the advancing social counter-revolution. It was the first organization to denounce the Articles, though, interestingly, its objections did not extend to what proved to be their most permanent weakness, Partition. It offered their republican opponents three quarters of the Workers’ Republic to make their case. Abandoning James Connolly, they would not present any social or economic demands until after civil war had begun.

Walter Carpenter had been acting secretary of the party from its foundation. He was elected Secretary of the party formally on 14 January 1922. It is doubtful whether he agreed fully with its line. Although politically opposed to the Labour Party, he was close to its stated view that the agreement had opened the way for the workers’ struggle to be ‘plainly and openly a struggle against capitalism’. His disagreement may have influenced his resignation as Communist Party secretary on 19 February, despite his public excuse of the pressure of his union’s business. He expressed his view at Labour’s Special Conference on Election policy on the 21st. Although he was a prominent member of an opposing body, the party/Congress’syndicalist organization meant that he could attend its Congresses and Conferences as delegate from his union. He took advantage to express his views:

‘Behind that document [The Executive’s Memorandum advising contesting the general election on the Agreement] there was the implication that the candidates going forth from the Labour Party would stand as Workers’ Republicans. They could not do this, for it was laid down plainly in the Constitution that they must stand as Labour candidates and nothing else. Why then talk of a Workers’ Republic? Those who worked for a Workers’ Republic were the men (sic) who seized the mills, the creameries and the railways. Russia did not bring the Workers’ Republic into operation by going into Parliament’ (A voice: ’It did.’) ‘No, but through direct action by Lenin and Trotsky.’ ( Irish Labour Party & TUC, Annual Report 1922, P.73.)

A narrow majority of delegates voted against his position and for contesting the election. More significantly, the Workers’ Republic ignored his speech. He continued as a quiet rank and file Communist until after the beginning of the Civil War.

At Labour’s 1922 Annual Meeting, he made two interventions. One was a motion that the party’s newly elected deputies refuse to take the oath of fealty to the King; it was referred to Standing Orders and disappeared. His other proposal was for Labour representation on Trades Boards to defend the interests of weaker workers.

The Communist Party continued with its new social and economic policy, but too late amidst the military-political polarisation for or against the Agreement with Britain. It was also too little for the Comintern leadership. It persuaded Roderick Connolly to publish articles urging a turn to industrial work. It was Connolly’s turn to return to the rank and file, but the Comintern’s line was inevitable, the party prospered and Carpenter chaired its Congress in April 1923. On Mayday, as Dr. Galvin has recorded, he was a speaker at a Labour Daymeeting of several hundreds.

The following August, he represented his union at Labour’s Annual

Meeting. As before, he defended Trades Boards; ‘In certain industries,

trades boards were of the utmost importance and should not be

scrapped, but strengthened, if possible.’ (Irish Labour Party & TUC,

Annual Report 1923, P.64.) He was accused of having helped republican

women attack delegates, but was cleared of this. (Ibid, P.P 71-72.)

Most constructive was his successful motion instructing the Executive

‘to organise for the celebration of May 1st 1924 and succeeding years

as a National Labour Day.’ (Ibid, P.84)

For all these successes, the Communist Party was in trouble again.

James Larkin had returned from America and, despite the party’s

expectations refused to join it. He set up a propaganda group around

his revived Irish Worker to be the Comintern’s Irish section. His

prestige attracted more potential Communists than the Party could. In

late September, Carpenter became editor of the Workers’ Republic but it

closed in November. In January 1924, the Comintern ordered the party

to dissolve into the Irish Worker League. The tailoring soviet had

gone bankrupt in June.

In March Carpenter attended a special Labour Party meeting as a man

without an organization other than his union. In what would be his

last recorded speech to such a gathering, he took a position attacking

both sides in the debate as to whether the new Irish Saorstat should

impose tariffs. This is a debate relevant today, but unlike most of

those speaking for either side then or now, he introduced his case

from a working class perspective which provided the context for the

subsequent three sentences that, on their own, would seem to have come out of the mouths of a contemporary capitalist government minister: ‘He was astonished to find Mr. Johnson quoting Connolly in support of protection. He understood Connolly to have been advocating efficient industrial unions, which would be strong enough to enable the workers to control industry and trade as they pleased. There was really only one industry in Ireland and that was agriculture. If they wanted to legislate for industry, that was the industry they should concentrate on. If it flourished, the country flourished.’ – (Irish Labour Party & TUC, Annual Report 1924, PP.39-40).

The capitalists’ continuing offensive backed by the government could

not have helped Carpenter’s health and must have hastened his

comparatively early death. It may also have sapped his will to argue

against the persuasions of the Religious Sisters of Charity, though it

can never be known how far his renunciation of his lifelong political

principles extended. This writer prefers to think that, as with the

confessions of many excommunicated IRA Volunteers in the same period, the nuns showed true Christian charity and interpreted a mild regret for past sins as a blanket renunciation of Marx and Connolly.

Certainly Dr. Galvin is correct here; ‘he had nothing to make up.’

With thanks to by D.R.O’Connor Lysaght .

For further information , corrections or clarifications please contact eastwallhistory@gmail.com