“I thought that no man liveth and dieth to himself, so I put behind what I thought and what I did , the panorama of the world I lived in- the things that made me.” Sean O’Casey (1948)

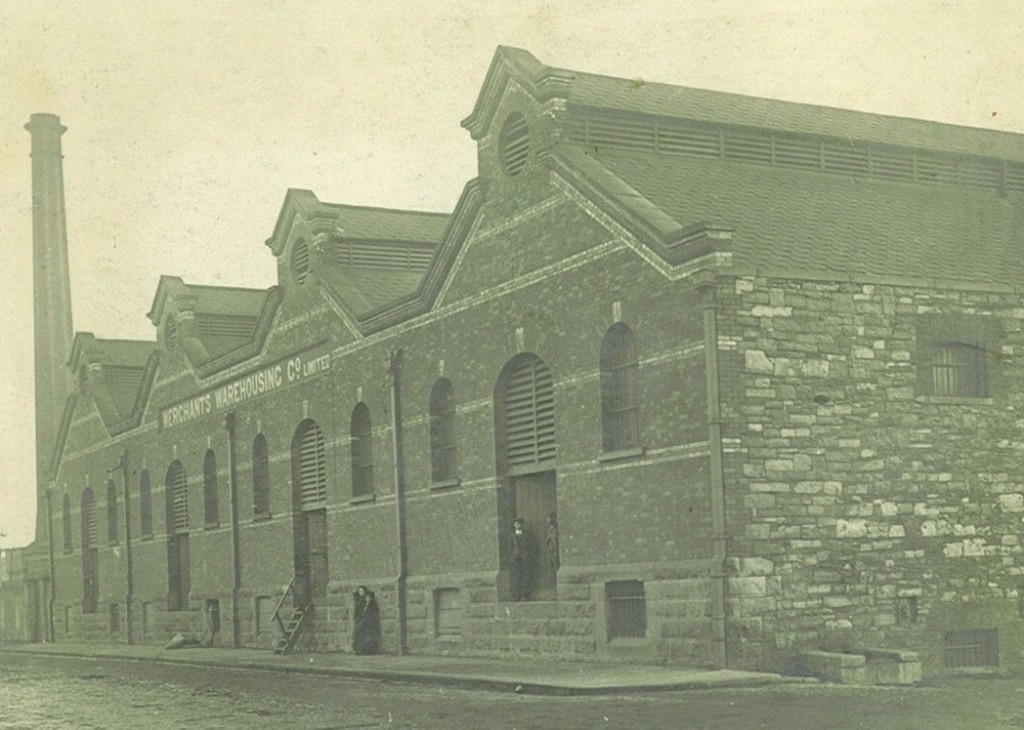

Between 1939 and 1955 Sean O’Casey published six volumes of Autobiography. The first three in particular contain much about his life as a North Dock resident. Throughout this anniversary year, marking 50 years since his death , we intend to present short extracts from these works , concentrating on sections which are most relevant to the area . Over three days we are featuring sections on events during the Easter Rising 1916. O’Casey was a non combatant in the Rising , and his account is very much from a civilians perspective , and is a unique record of events locally , not recorded elsewhere. In our final 1916 excerpt we move onto the events of Wednesday and Thursday , the third and fourth day of the insurrection , as Sean and his neighbours are held prisoner in a grain store (most likely to be the Merchants Warehousing Company) , rumours abound and a meal is finally procured.

“The next evening, all the lusty men of the locality were marshalled, about a hundred of them, Sean joining in, and were marched under guard (anyone trying to bolt was to be shot dead) down a desolate road to a great granary. Into the dreary building they filed, one by one; up a long flight of dark stone steps, to a narrow doorway, where each, as he came forward, was told to jump through into the darkness and take a chance of what was at the bottom. Sean dropped through, finding that he landed many feet below on a great heap of maize that sent up a cloud of fine dust, near choking him. When his eyes got accustomed to it, he saw a narrow beam of light trickling in through some badly shuttered windows, and realized he was in a huge grain store, the maize never less than five feet deep so that it was a burden to walk from one spot to another, for each leg sank down to the thigh, and had to be dragged up before another step could be taken. It took him a long time to get to a window, and crouch there, watching the sky over the city through a crack in the shutters. A burning molten glow shone in the sky beyond, and it looked as if the whole city was blazing. One ear caught the talk of a group of men nearby who were playing cards. He couldn’t read Keats here, for the light was too bad for his eyes. More light, were the last words of Goethe, and it looked as if they would be his last words too.

-I dunno how it’ll end, said one of the card-players; the German submarines are sweepin’ up th’ Liffey like salmon, an’ when they let loose it’s goodbye England. My trick, there eh!

-I heard, said another player, that th’ Dublin Mountains is black with them – coal-scuttle helmets an’ all – your deal, Ned.

-Th’ Sinn Feiners has taken to an unknown destination that fella who ordehered the Volunteers in th’ counthry to stay incognito wherever they were - what’s his name? Oh, I’ve said it a hundhred times. What’s this it is?

-Is it Father O’Flynn? Asked a mocking voice in a corner.

-No mockery, Skinner Doyle; this isn’t a time for jokin’. Eh, houl’ on there – see th’ ace o’ hearts!

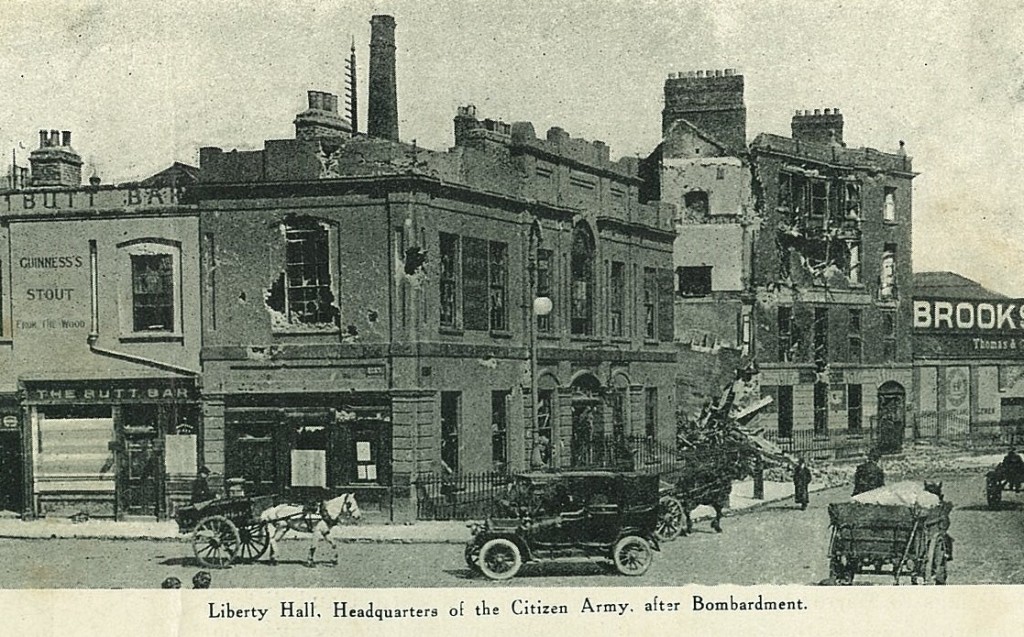

Then they heard them, and all the heads turned to where Sean was crouching at the window; for in the fussy brattle of ceaseless musketry fire, all now listened to the slow, dignified, deadly boom of the big guns.

-Christ help them now! Said Skinner Doyle.”

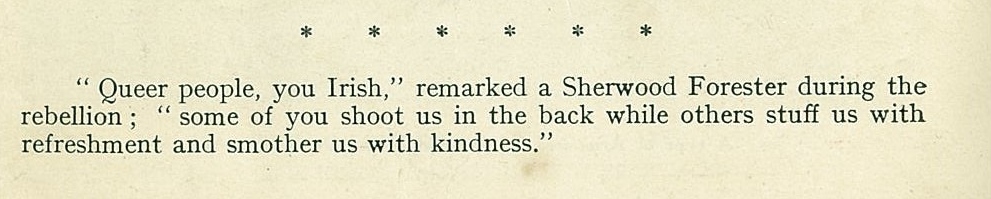

“Next day, he heard his name called from the hole at the end of the store where the sentry stood. Wading through the corn, he was told to leap up, and leaping, was caught by a corporal who helped him to scramble to the floor above. He was to go home for a meal, accompanied by a soldier, for a while the rest were permitted to disperse home for an hour, they were suspicious of him because his room was the one that received the fire from those searching out a sniper. He was covered with the dust of the corn, and though he had pulled up the collar of his coat to protect the wound in his neck, he felt the dust of the grain tearing against its rawness and felt anxious about it. But he had to be patient, so he trudged home, silent, by the side of the soldier. When he sat down, and, in reply to the soldier’s question, said there was nothing in the house with which to make a meal,

-Wot, nothink? asked the soldier, shocked. Isn’t there somewhere as you can get some grub?

-Yes, said Sean; a huckster’s round the corner, but I’ve no money to pay for it.

-E’ll give it, ‘e’ll ‘ave to; you come with me, said the Tommy; Gawd blimey, a man ‘as to eat!

So round to Murphy’s went the Saxon and the Gael, for food.

Murphy was a man who, by paying a hundred pounds for a dispensation, had married his dead wife’s sister, so that the property might be kept in the family; and Sean thought how much comfort and security for a long time such a sum would bring to his mother and to him. The soldier’s sharp request to give this prisoner fella some grub got Sean a loaf, tea and sugar, milk in a bottle, rashers and a pound of bully beef. On the way back, Sean got his mother, and they had a royal meal, the soldier joining them in a cup of scald.”

Extracts from “Drums under the windows” (1945)

All six volumes of Sean O’Casey Autobiographies, republished by Faber and Faber , are currently available in both print and kindle editions.

If you have a favourite Sean O’Casey extract please bring it to our attention .

Contact us at eastwallforall@gmail.com