May 04

1916: The destruction of Liberty Hall & Walter Carpenter

“For many years past, Liberty Hall has been a thorn in the side of the Dublin Police and the Irish Government. It was the centre of social anarchy, the brain of every riot and disturbance.” - Irish Times 1916

During the week of the Easter Rising Liberty Hall was extensively damaged by British artillery. Some months later a number of compensation claims were made relating to the destruction, including one lodged by Walter Carpenter. It was unsuccessful, but quite interesting all the same.

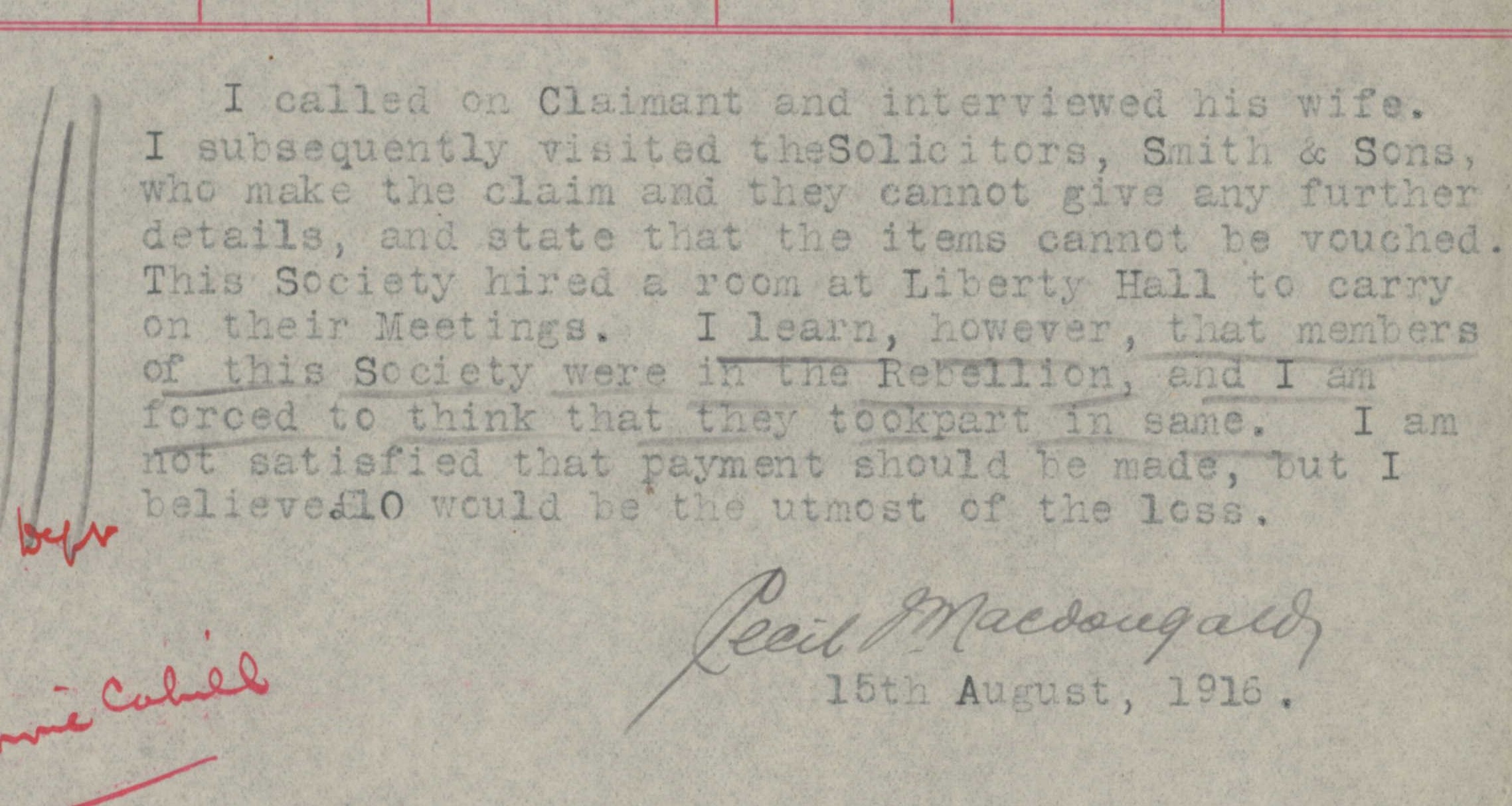

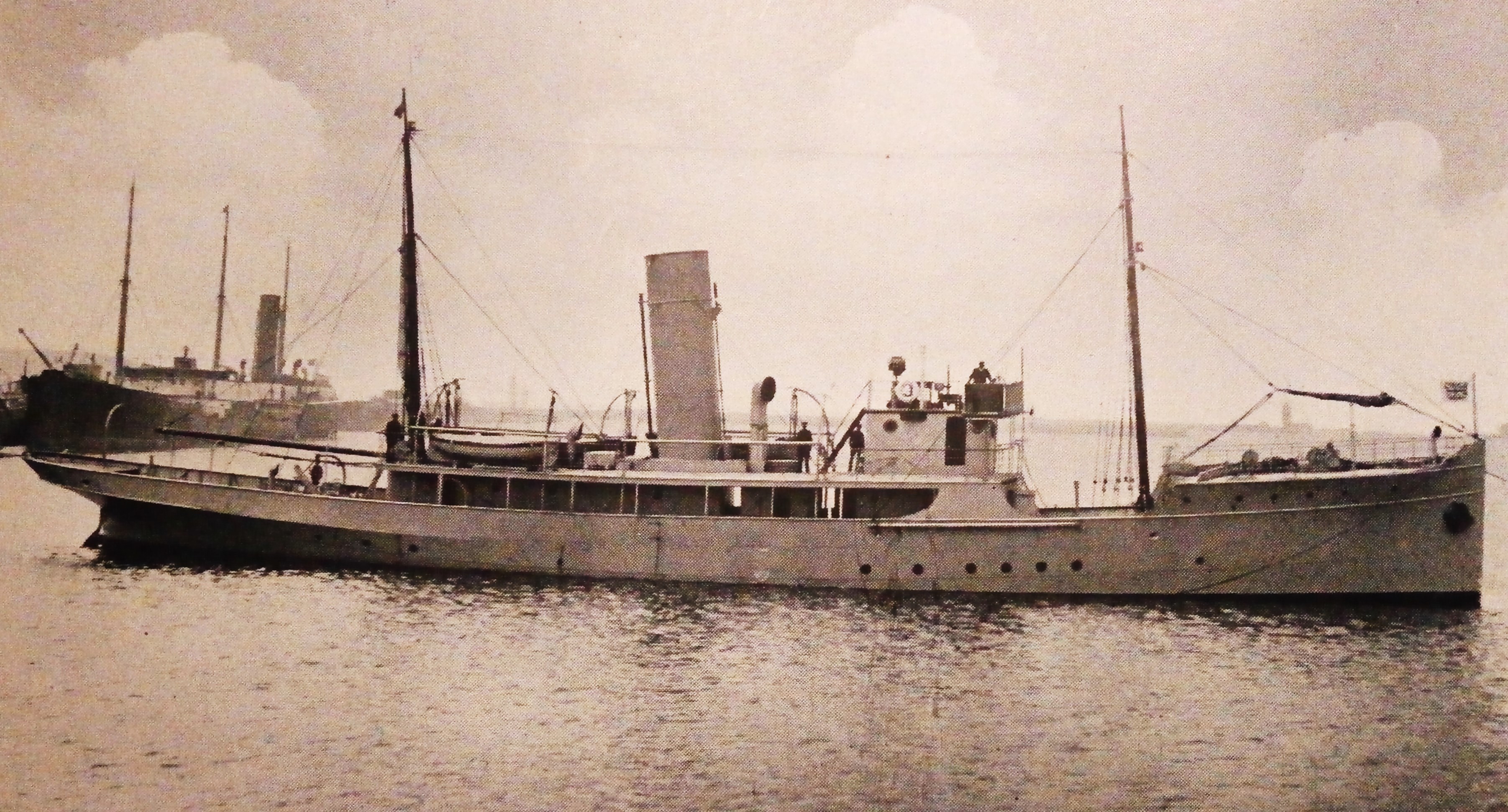

Despite the fact that it was empty, Liberty Hall was considered a prime target by British forces and came under persistent attack, with a clear aim to destroy the building. They failed. While high explosive shells were fired from the Gunboat Helga positioned on the Liffey, the loop line bridge obstructed its trajectory and made the building difficult to strike. A field gun was also positioned at Tara Street which had a clear, unobstructed view of the building, but as it was firing shrapnel rounds its destructive ability was limited. While the building was extensively damaged and much of its interior and contents destroyed, it did not suffer as badly as some adjacent structures. Importantly, it did not catch fire, which would prove to be the real cause of damage elsewhere in the City Centre.

The above opinion of Liberty Hall –“a thorn in the side…”, and “the centre of social anarchy…” etc was not entirely without foundation. The building (formerly a hotel) had been acquired by Jim Larkin and the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU) in 1912. As well as being the union headquarters, it also became home to all manner of political, social and workers organisations and initiatives.

One of the groups which would have it’s office here was the Socialist Party of Ireland. James Connolly had returned to Dublin from Belfast to become a full time organiser with the party, alongside East Wall resident Walter Carpenter who was secretary. Confusingly, the party operated under the title of Independent Labour Party (though not affiliated to the British Party of the same name), and it was as the ILP that they acquired a room from Jim Larkin. Many members of the party would be regular speakers at the rallies and demonstrations that took place at Beresford place throughout the era of radicalism that was occurring. In 1911 James Connolly would address a welcome home rally for Walter Carpenter when he was released from Mountjoy Prison, while in 1913 Walter would speak at a similar welcome home for Connolly. On the 16th April of 1916 Carpenters son, also Walter, commanded the Citizen Army Boys outside the building when Molly O’Reilly raised the republican flag. The party was still based here in Easter Week, and their office suffered in the bombardment.

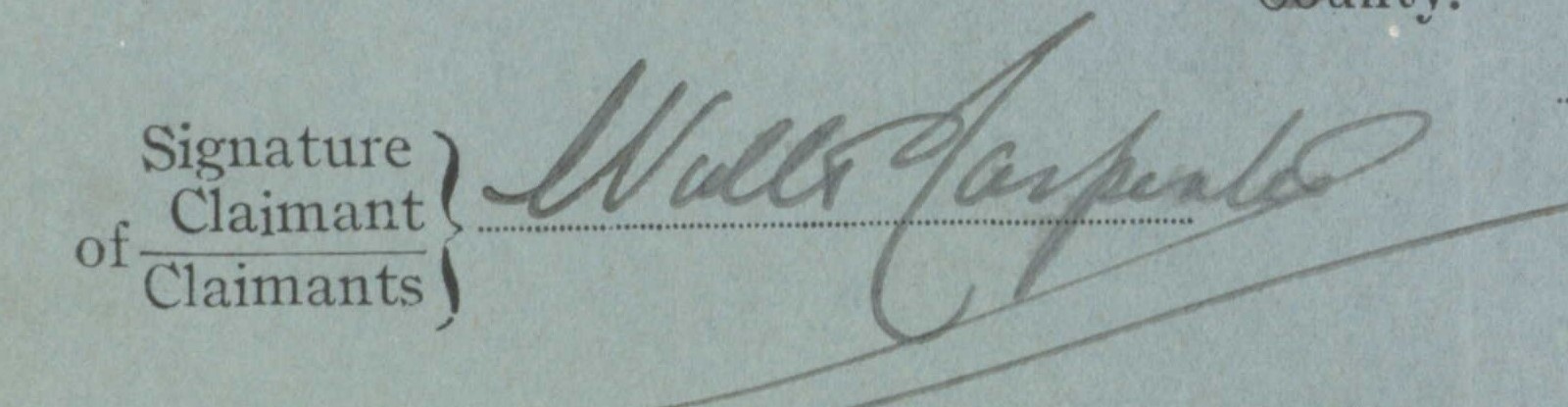

In response to the damages caused during the Rising , the ‘Property Losses(Ireland) Committee ,1916 ‘ was established , to address claims made for “Damages caused during the Disturbances on the 24th April, 1916 , and following days” . Walter Carpenter, acting as secretary to the Independent Labour Party of Ireland lodged their claim for compensation on the 1st August, just three months after the Insurrection.

The claim was in relation to items from the party offices, and referred to Goods damaged by “reason of the artillery used by His Majestys Troops, breaking and destroying same”. Notable among the damaged and destroyed items was the “Book case with about 300 volumes”.

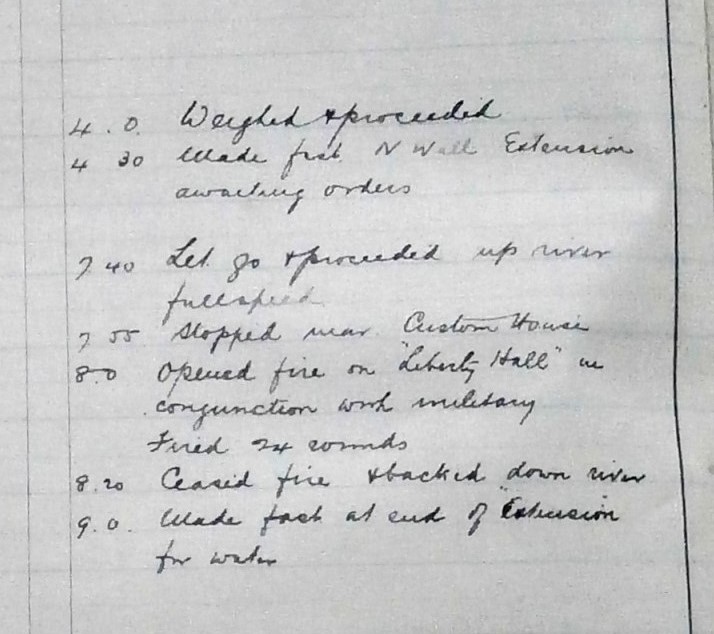

Unsurprisingly, the claim was rejected. The reasons given were to the point - “This society hired a room at Liberty Hall to carry on their meetings. I learn however that members of this society were in the Rebellion, and I am forced to think they took part in same. I am not satisfied that payment should be made…”

Again, these views were not without foundation. Walter Carpenter was indeed a declared revolutionary, and his sons Wally and Peter had indeed taken part in the rebellion. Both had become volunteers in the Irish Citizen Army at its foundation in 1913 and served as part of the GPO Garrison. While Walter continued his activities as part of the Socialist Party of Ireland, and while pursuing this claim on their behalf, his comrade and friend James Connolly had been executed, and his son Peter was currently residing at Frongoch Internment Camp in Wales.

For comments , corrections or clarifications contact: eastwallhistory@gmail.com

(Images from Compensation papers : NAI/PLIC/ 4828 . Courtesy National Archives of Ireland , used with permission )

Apr 30

‘I am Muirchú’ by Rita Edwards (Remembering the Helga)

‘I am Muirchú’

by

Rita Edwards

I am Muirchú the ‘Hound of the Sea’. I was not always known as Muirchú. When I was built in the Liffey Dockyard in Dublin in 1908 – a steam yacht with 323 tons displacement, capable of reaching a speed of 14.6 knots – I was named Helga II. There must have been a Helga I but I don’t know anything about her.

Helga is an Old German/Old Norse name which can mean ‘holy, sacred or successful’. When I was first launched I worked as a fishery protection vessel for the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction (Ireland). I spent my time patrolling the Irish coast protecting the fishing grounds.

Six years later I overheard the crewmen saying that the world was at war. In 1915 I was taken over by the English Admiralty and renamed HMY (His Majesty’s Yacht) Helga. I was then equipped with artillery and other guns on my deck. When they fired, the noise was deafening.

My work got harder. I now served as an anti-submarine patrol vessel. In April 1918 I attacked a German submarine off the Isle of Man. For the remainder of my career I carried a star on my funnel in recognition of my achievement. I remained on escort duty in the Irish Sea, making sure that other ships arrived safely at their destination.

In April 1916 I left the sea and sailed up the River Liffey in Dublin where my guns shelled Liberty Hall and other buildings. Within a few days, with support from other artillery positions, the centre of the city was in flames.

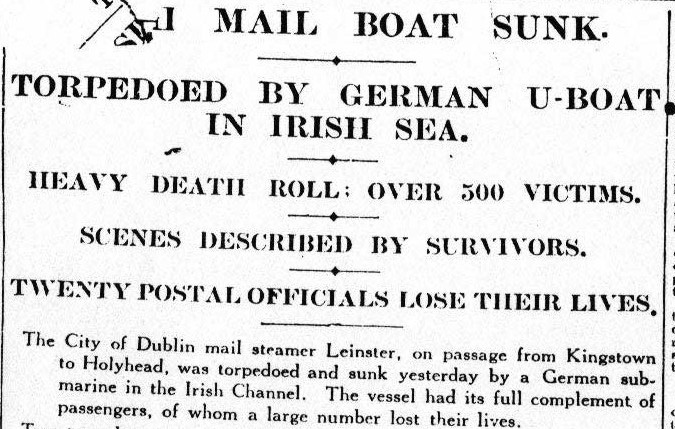

Over two years later in October 1918 I was taking on fuel in Kingstown Harbour when the RMS Leinster, the Dublin-Holyhead mail-boat was torpedoed near the Kish Lightship by another enemy submarine. I sailed out the seven miles and brought ninety of the survivors back safely into harbour.

For a short time, I was back doing the work I loved – patrolling the Irish coast protecting the fishing grounds. However, no sooner had one war ended when another war began. From March 1920 I carried men in black and tan uniforms from one Irish port to another.

Then peace reigned for a while until June 1922 when there was another war and I was commandeered by a new Irish Free State to transport other men in dark green uniforms from one Irish port to another.

I grew tired of war. During all the years, in keeping with my name, sometimes my work was holy, sometimes it was sacred, sometimes it was successful – but all too often, it was simply profane.

Eventually in August 1923 I became the property the Free State and the new Irish Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and renamed the SS Muirchú – the Hound of the Sea. And once again, I was back patrolling the Irish coast protecting the fishing grounds.

But peace did not last. Sixteen years later in September 1939 the dogs of war were unleashed again. Up to then the Free State did not have a navy. Due to a lack of ships, I had the distinction of being one of the first ships in the new Irish navy in the Marine and Coastwatching Service.

I served faithfully until the end of that war, by which time the marine service had ten sea-going ships. Then it became apparent that I had outlived my usefulness. For a time I was kept in dry dock in Cobh in Co Cork. Then I overheard that I was to be decommissioned and sold to Hammond Lane Foundry in Dublin.

On the 8 of May 1947 which was the day appointed for me to make my final voyage to Dublin Bay I decided that for once I would take control of my own fate. As I approached the Saltee Islands off Kilmore Quay in County Wexford, I loosened the rivets in my bow just below the waterline. In a short time, I started to list. I waited until the crew had time to abandon ship and then slowly, I sank beneath the waves.

After all, I am Muirchú– the hound of the sea and it is fitting that I should rest on its welcoming bed, instead of being brought to Dublin – the place where I first felt cool water against my hull – to be broken up for scrap.

(The brass ship’s bell of the SS Muirchú was subsequently salvaged and can be seen at ‘The Irish At Sea’ exhibition which forms part of the ‘Soldiers and Chiefs’ exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks, Dublin.)

Printed courtesy Rita Edwards. Originally appeared in the Liffey Champion (23rd April)

Rita Edwards is an Enniscorthy woman and an historian who now lives in Maynooth in Co Kildare. She is a graduate of Maynooth University and specializes in the history of her home county, Wexford. In addition to contributing to local journals and magazines, both in Kildare and Wexford, her work includes the development of ‘Kilmore Quay, County Wexford, 1800-1900’ which was published in Irish Villages – Studies in Local History (2004) and ‘Enniscorthy: Mean Village to Fine Town’ in Enniscorthy – a History (2010).

Apr 25

Sean O’Casey and the fighting men of 1916

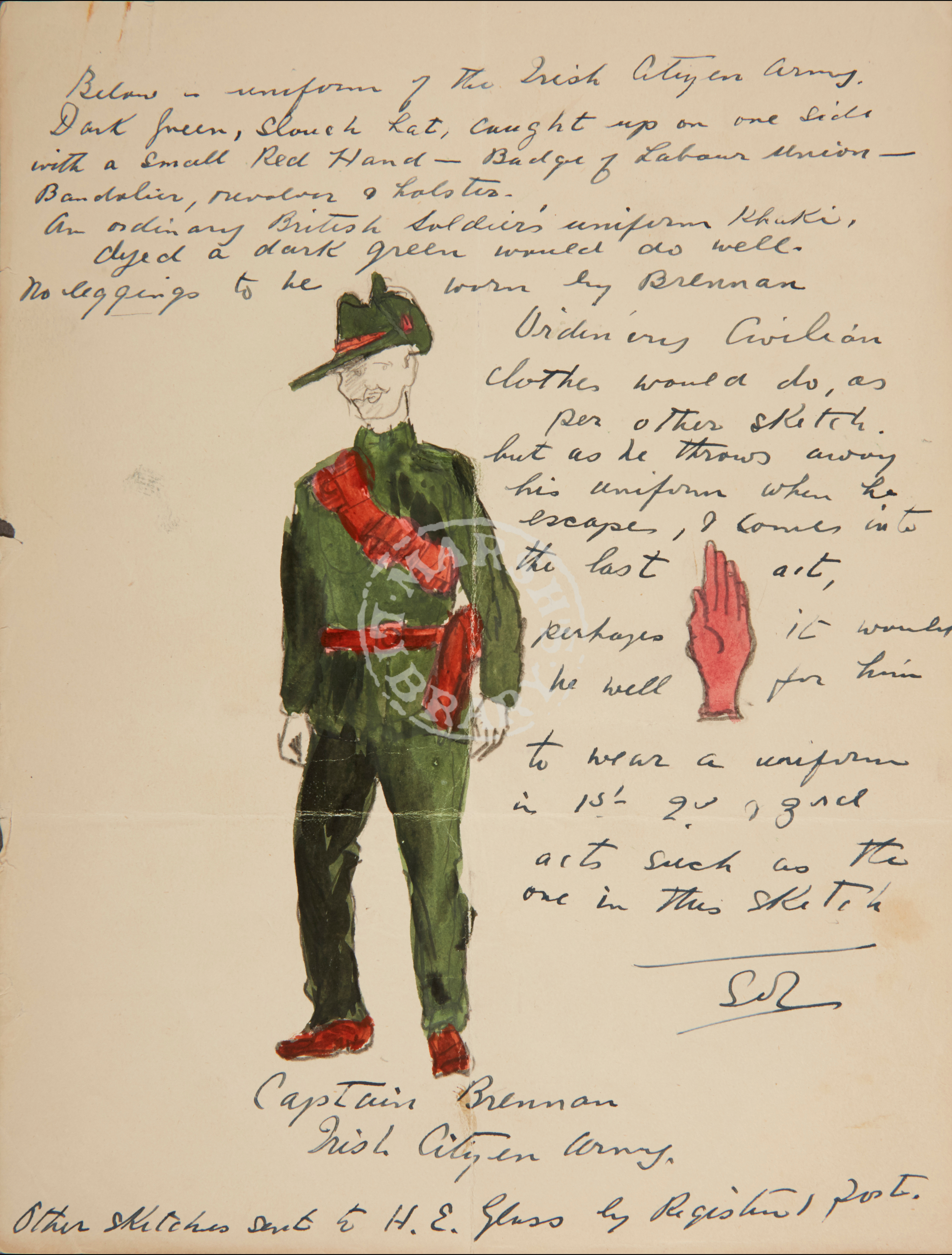

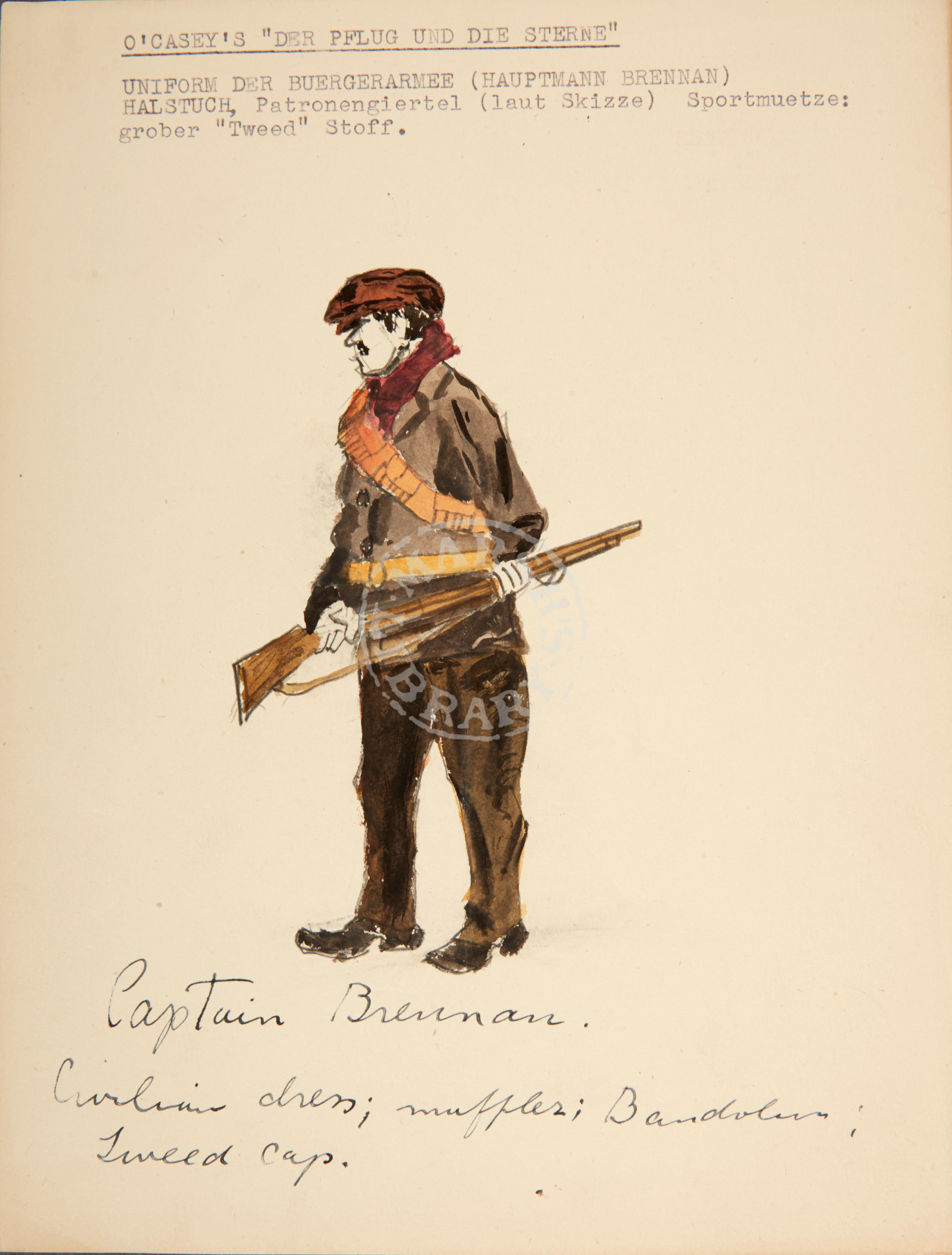

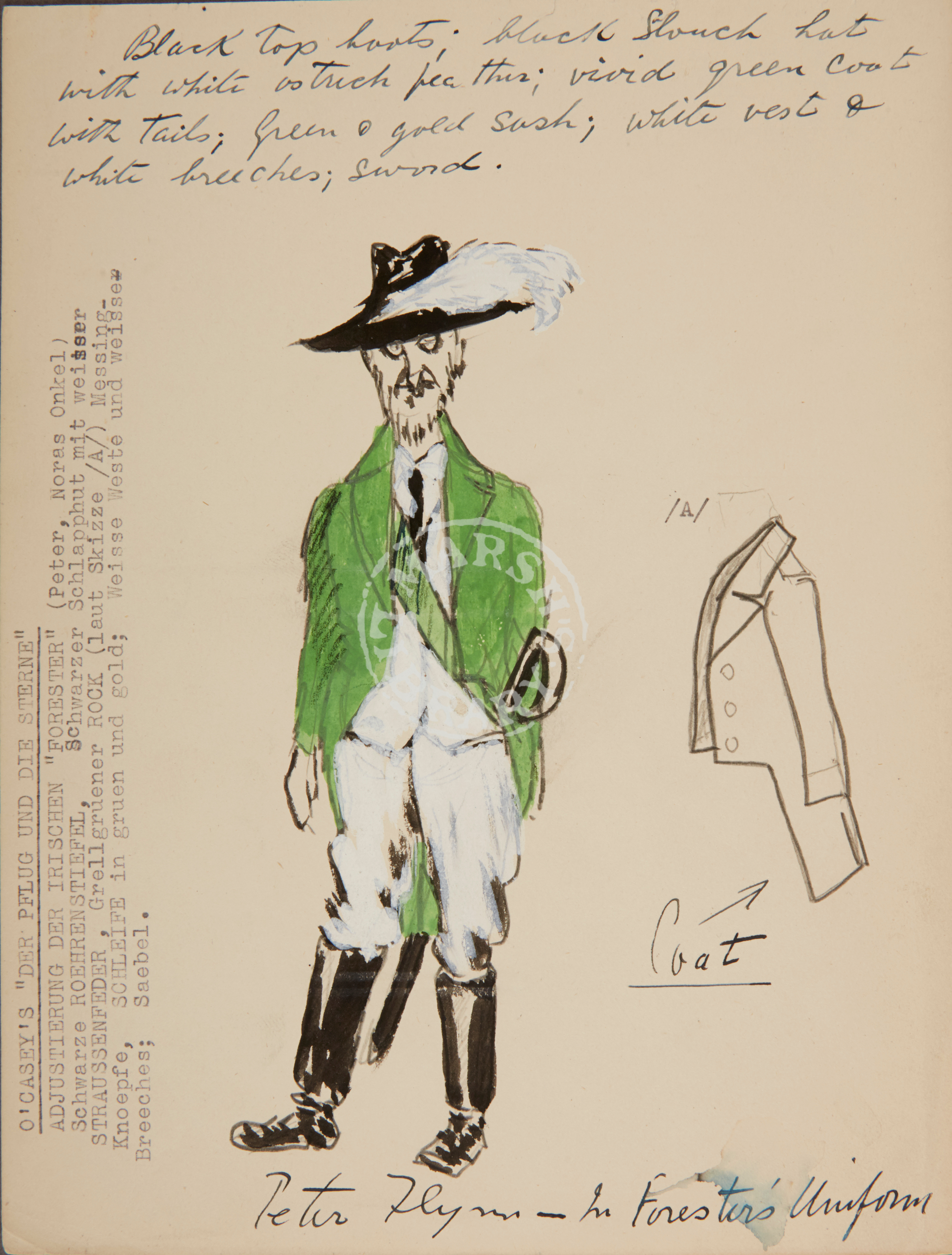

These four watercolours by Sean O’Casey illustrate some of the uniforms worn by the fighting men of the 1916 Rising. O’Casey had been a founding member and secretary of the Irish Citizen Army in 1913 until he resigned in 1914. He was not a combatant in the Rising though he was caught up in the events, almost being shot by a British sniper and interned during a round up of residents in the North Docks. The watercolours were painted by Seán O’Casey in the 1930’s to provide costume details for a German production of The Plough and the Stars.

(The watercolours are normally held in the Benjamin Iveagh collection at Farmleigh House. They were donated to Marsh’s Library by the Guinness family and are managed by the Office of Public Works).

These four watercolours are currently on display at Marsh’s Library in their exhibition ‘1916: Tales from the Other Side’. The exhibition uses a unique archive of books, manuscripts and artefacts to trace how minority communities responded to the tumultuous events of the Irish revolution.

The exhibition runs until December 2016, and is free with entrance to the library (€2/€3). Opening Times: 9.30am – 5.00pm on Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday; 10.00am – 5.00pm on Saturdays; closed Tuesdays and Sundays).

(All images used with permission of Marsh’s Library and the O’Casey family and is greatly appreciated)

Apr 10

The Lost Life of Paddy Lynch; GPO Garrison 1916

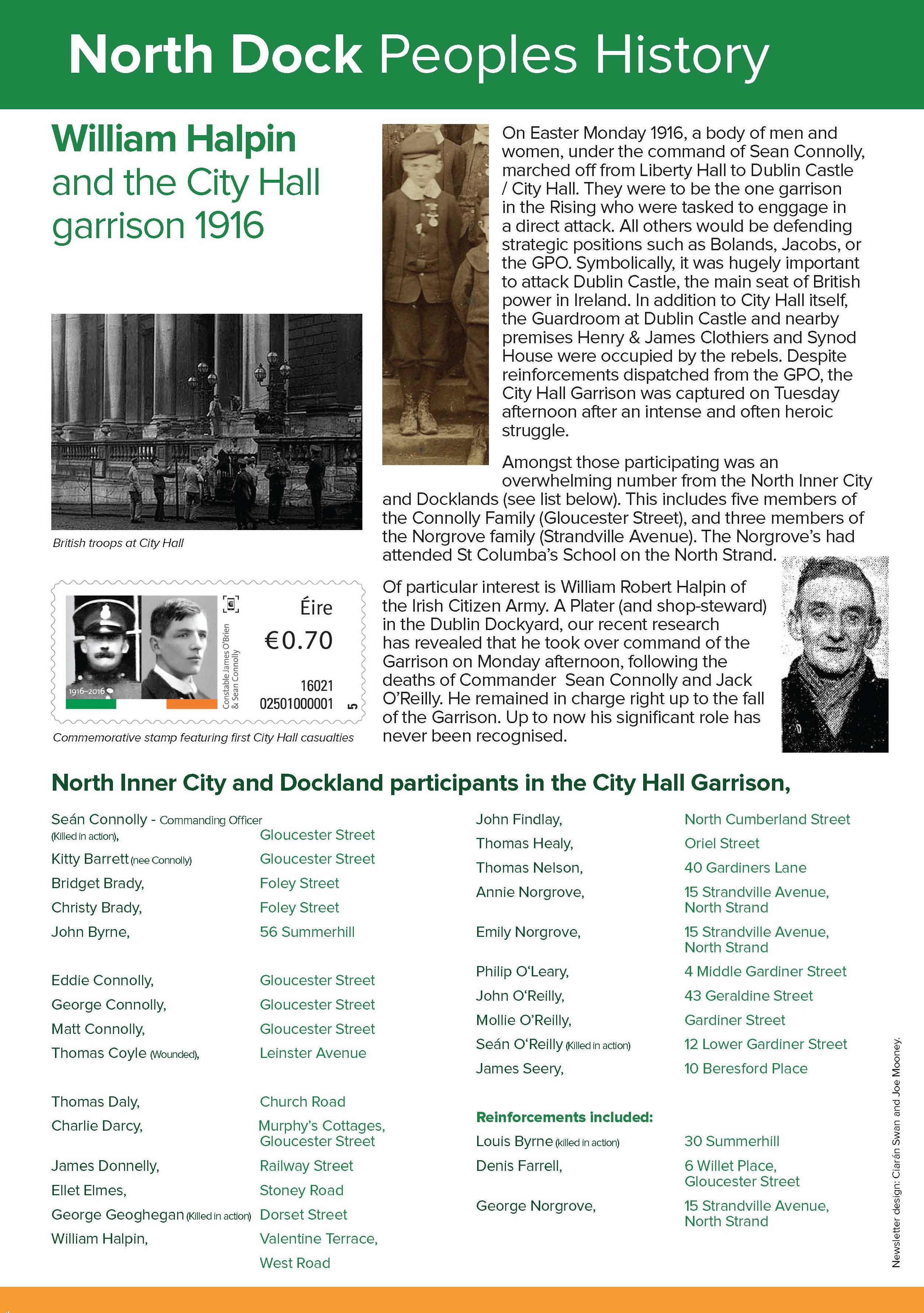

“I saw him being shot. He was not shot with his own gun. He was hit in the neck. It happened just outside the wall of O’Briens Mineral Water Factory in Moore Lane”.

The photo above shows a bullet riddled building on Moore Lane, a shocking indication of the ferocity of the fighting which took place during the retreat of the GPO garrison, as the Easter Rising moved towards it’s conclusion.

Paddy Lynch of the Irish Citizen Army died here. In the late 1920′s , with the advent of the Military Service Pensions, his sister Anne Donovan had made an application, on the basis that she had been solely dependent on him at the time of his death. She had raised him from childhood, was widowed, and now aged in her late 50’s and in ill health. Her application was unsuccessful. Attempts by the pension’s assessors to establish the facts of his death and details of his ICA service were made difficult by conflicting recollections, confusion over the events during the retreat and a lack of supporting documentation. Despite ongoing efforts, by the time of her death in 1937 a satisfactory conclusion had not been reached. Paddys name was featured on a memorial in Glasnevin, but ‘disappeared’ during a refurbishment in the 1960’s. This is the story of Patrick ‘Paddy’ Lynch of the Irish Citizen Army, a ‘lost life’ in every sense of the word.

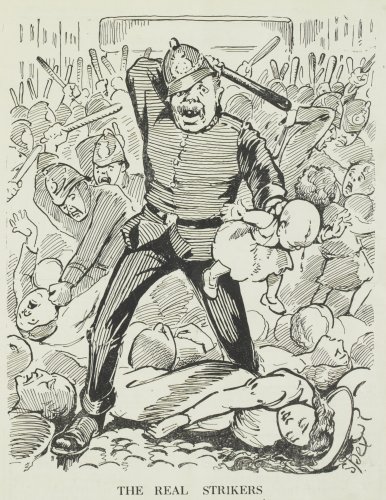

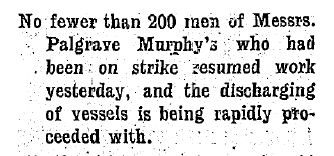

On the 26th August 1913 workers of the Dublin United Tramways left their vehicles and went on strike to ensure the recognition of the Trade Union of their choice, the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU). Five days later at a mass rally in support of the workers, the Dublin Metropolitan Police, both mounted and un-mounted, charged the crowd in O’Connell Street. The events, which became known as Bloody Sunday saw the deaths of two people and the injuring of hundreds more. With the battle lines drawn and attitudes hardening sympathy strikes broke out all over the city. On the 2nd of September the Coal Merchants Association locked out their workers, followed by the Building Trade Employers Federation the following week. Over the coming months violence became more common with the Royal Irish Constabulary opening fire on agricultural workers in the more rural areas of Dublin such as Finglas. As the strike spread across the city over 200 dock workers of Palgrave Murphy Shipping Agents went out on strike on the 9th October and would remain out until the end of the year. Among those who ended up in that strike was Paddy Lynch from the North Docks, who had worked with the company for a number of years. When the strike collapsed most of the Palgrave Murphy strikers got their jobs back. But not Lynch, who didn’t return their until shortly before the Rising in 1916. By the end of that Easter Week he would be dead.

The Lynch’s were just another of those late nineteenth century inner-city families whose main purpose in life seemed to be in contributing to Dublin’s appalling annual mortality statistics. At least four children were born to Patrick and Mary Anne Lynch between 1868 and 1880 but there were possibly more. Almost all of them died. Eventually both Patrick and Mary Anne succumbed to one or other of the myriad of diseases which pervaded the city, leaving their eldest daughter Ann Elizabeth to bring up her younger brother Paddy. In 1910 Ann Elizabeth married John Donovan, who would himself die just three years later. She never remarried.

Unfortunately we know very little about the life of Paddy Lynch. The fact that he remained out of his job when so many were re-employed after the Lockout would suggests that he played a more active role in the strike activities on the docks and was black-listed for this. The birth records for a number of his siblings suggest he was born at Aldeborough Parade but it has proved difficult to find one for Patrick himself.

Police violence against inner-city dwellers was a normal part of Dublin life, particularly over weekends, with certain DMP station being particularly notorious. But the violence displayed during the Great Lockout was different. Cathleen Seery from Beresford Place who stood in front of the police horses as they attempted to ride the protesters down on ‘Labours’ Bloody Sunday recalled that she had never experienced the naked hatred she witnessed on their faces that day. She was convinced that they came out that day to kill and maim. In order to protect the striking workers and their families an organised defensive body was formed which would soon become the Irish Citizen Army. Paddy Lynch was an early recruit to this workers militia.

ICA at Croydon Park 1914 . Includes Countess Markievicz , Captain Jack White and Francis Sheehy Skeffington.

However, following the ending of the Lockout, Lynch, like thousands of others, found himself out of work, and eventually took the time honoured route to Glasgow in search of employment.

Lynch returned regularly from Glasgow, being his sister’s main financial support at this time. It’s claimed that he maintained contact with the ICA throughout this period. It wasn’t long after James Connolly took command that the Citizen Army began to transform from a Defensive body to an Insurrectionary Force. From a very early stage he had began using the Glasgow route to import arms and explosives into Dublin City. It is possible Lynch may have been part of this clandestine operation, which may explain why he obviously had very little contact with the ICA rank and file in these years and many would have difficulty recalling him.

(There are suggestions that he took part in the Howth Gunrunning on the 26th July 1914. This seems unlikely as the Gun-running was an Irish Volunteers operation and the ICA and Volunteers were going through a period of antagonism at this time. However quite a number of the rifles landed at Howth that day ended up at Croydon Park and Lynch may well have been one of the ICA men on duty who “acquired” rifles as the Volunteers faced down the DMP and the Royal Scottish Borderers on the Malahide Road. Lynch’s friend Richard Corbally, a fellow Citizen Army man and Carter, made claims of his own involvement, which we believe almost certainly involved picking up rifles hidden by the Volunteers in the fields of Marino).

In early 1916 he returned to live in Dublin and regained his job with Palgrave Murphy’s. (Exact details are scarce , as Palgrave’s employment records were destroyed when the Company was wound up and reorganized in 1926 .By the 1930’s the foreman, Maurice Farrell, who lived at Scallys Cottages off Mayor Street, had no recollection of Lynch having ever worked there when asked about him).

There were many men who having defied the Dublin Bosses in 1913 would go to War with the British Empire in 1916. We will probably never establish fully the sequence of events which led him there, but there is little doubt that Paddy Lynch was amongst those situated at the GPO during Easter Week. On Friday 28th April, with the building blazing fiercely around them, the decision was taken to evacuate the garrison up Henry Place towards Moore Street. Coming around the corner or the “L” as one witness described it, Lynch was hit in the neck and died instantly without speaking, collapsing outside the wall of O’Brien’s Mineral Water Factory. His death occurred amidst chaotic scenes, with the accompanying photographs illustrating the intensity of the combat. It was dark and Henry Place was filled with smoke and fumes from burning buildings nearby. The British had machine guns at the Parnell Street entrance to Moore Lane with snipers and machine guns on the roof of the Rotunda Hospital. A number of insurgents would die in the general vicinity. Richard Corbally detailed the exact location, as did Vincent Poole (who knew Lynch and also recalled seeing him in the GPO). Poole stated it was definitely here where he was shot, and in the confusion, Oscar Traynor, Sean McGarry, Paddy Slattery, Gerry Boland, and Sean Milroy all stepped over his body as they attempted to cross Moore Lane.

When questioned by the Military Service Pensions Board all these men remembered fatalities they witnessed – a volunteer killed breaking down the door or a man whose ammunition pack was hit and exploded near O’Briens. However, neither of these incidents was Paddy Lynch. Oscar Traynor suggested that the body in question was that of Harry Coyle (though it was claimed elsewhere that Coyle was actually shot beside the O’Rahilly in Sackville Lane).

Michael Delaney swore that Lynch had been a member of the Citizen Army from 1913 and stated he knew that Lynch had been in the GPO. However he hadn’t actually seen him there or in the retreat, and said he was told that Lynch had been killed. He also claimed that Lynch only arrived back in Ireland from Glasgow about 10 days before the Rising. Michael O’Murchu did recall seeing an ICA man in the GPO, and that he had handed his shotgun to the O’Rahilly who used it to shoot down a sign in Prince’s Street which obscured the view of O’Connell Street. He assumed this was the same man killed when his shotgun went off as he used it to break into a house opposite O’Brien’s Mineral Water Factory, and believed this to be Lynch. A reasonable assumption, however, Bill O’Brien (at this stage the head of the ITGWU), claimed that the man killed in this manner was in fact Charles Corrigan who had come over from Glasgow to fight with the ICA.

Richard Corbally was very clear in his recollection: “I saw him being shot. He was not shot with his own gun. He was hit in the neck. It happened just outside the wall of O’Briens Mineral Water Factory in Moore Lane”.

Corbally also detailed how Lynch regularly paraded with the unit under the command of Sean Connolly prior to the Rising. Unfortunately, as Connolly was killed, as was his Sergeant John O’Reilly at the City Hall in 1916 this could not be verified. The casualty rate had been high there and by the 1930s it was near impossible to find anyone who could corroborate Corbally’s statement. Those who knew Lynch all believed that he continued to make trips to Glasgow, with Corbally claiming that he went for several weeks before the Rising. However, as with much of the evidence supporting his sister’s pension application there were conflicting elements.

A further complication was the fact that Lynch’s name didn’t appear on the mobilization book compiled by Tom Kaine towards the end of 1915. This was later used to compile a roll of ICA participants in the rising by John Hanratty. Matters were further complicated when Seamus McGowan and Michael Kelly both cast doubts on Lynch’s participation. McGowan claimed that as treasurer of the ICA he should have known Lynch but he didn’t. (However there were periods between 1913 and 1916 when William Halpin was treasurer of the ICA which may have covered Lynch involvement). Michael Kelly, part of the High Street section of the ICA and who fought at Stephen’s Green, privately stated that he thought the case might be a “try on” by Lynch’s sister but wouldn’t go on record over it just in case it was genuine.

Bill O’Brien, while prepared to accept that Lynch was a member of the ICA and had indeed been involved at the GPO in Easter Week found it impossible to get corroboration. It is worth noting that those he questioned – Frank Robbins, Seamus McGowan, Michael Kelly, John Hanratty, and Sean “Gurra” Byrne, while senior figures in the ICA after Easter Week were ordinary private soldiers in the years leading up to it and may well not necessarily have had much contact with Lynch. O’Brien also pointed out that Lynch was not on the list of dead compiled by the Irish National Aid and Volunteers Dependents Fund, but that the organization had given £40 to Lynch’s sister. Similarly while James O’Neill stated that it would have been impossible for him to know Lynch (given his own involvement being with the Lucan Company between 1913 and ’16), the White Cross, of which he was a board member, had given Lynch’s sister £100.

Much of the difficulty involved in determining Lynch’s case revolved around the location of O’Brien’s Mineral Water Factory in Henry Place. A Volunteer had been killed while trying to break into a house on the laneway using the butt of his shotgun. However this took place at the factory near the entrance onto Moore Street and beside No. 10 which the volunteers made their initial HQ. Both Sean McLoughlin and Diarmuid Lynch recalled that a number of men were killed at the warehouse and stables of O’Brien’s further back up the laneway near the intersection with Moore Lane beside the building known as The White House. Irish Volunteer Michael Mulvihill was also killed near the same spot. A number of bodies were later taken away and buried in a mass grave at Glasnevin Cemetery.

Ann, the sister of Paddy Lynch did know he was dead until four months later. She was informed of his death by Richard Corbally when he was released from Frongoch. Up until that point she “was hoping that he was interned”. She did not know who had buried her brother, as it had taken place without her knowledge. She repeatedly stressed that he was “buried without a coffin” which evidently was a matter of concern for her.

A fundraising leaflet produced in 1917 listed Lynch as buried in grave JA 38 in Saint Paul’s Cemetery with other volunteers such as Edward J. Costello, Edward Byrne, Sean Hurley, Louis Byrne, Patrick Shortiss, and Patrick O’Connor. Later in 1929 a memorial was erected which listed Paddy Lynch (in Irish) as among the dead resting there. However in 1963 it was decided to replace the headstone-like memorial with a more substantial monument and in the process Lynch’s name vanished from the list. With almost all records relating to him having vanished or proving difficult to trace it was as if he had never existed.

In this centenary year, as we mark these momentous days in our Nations story, not only were the exact details of his death lost to history, but the very details of his life had almost vanished , reducing his contribution to his country to nothing.

However the National Graves Association has undertaken a major refurbishment of their the monument in St Paul’s , Glasnevin Cemetery. We believe that the name of Patrick Lynch has been restored and he will once again appear among the list of those who made the ultimate sacrifice in the Irish Revolutionary Struggle.

In memory of Patrick Lynch, Dock Labourer and

Soldier of the Irish Republic

Any comments, corrections or clarifications please contact us at eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Photo Credits:

‘Moore Lane , after the battle’ Courtesy : National Museum of Ireland / Gallery of Photography

‘ICA at Croydon Park’ , Moore Lane and Glasnevin memorial Courtesy: Hugo McGuinness

Sources include:

BMH Military Service Pensions Collection.

“They died by Pearse’s Side” by Ray Bateson (2010)

Mar 25

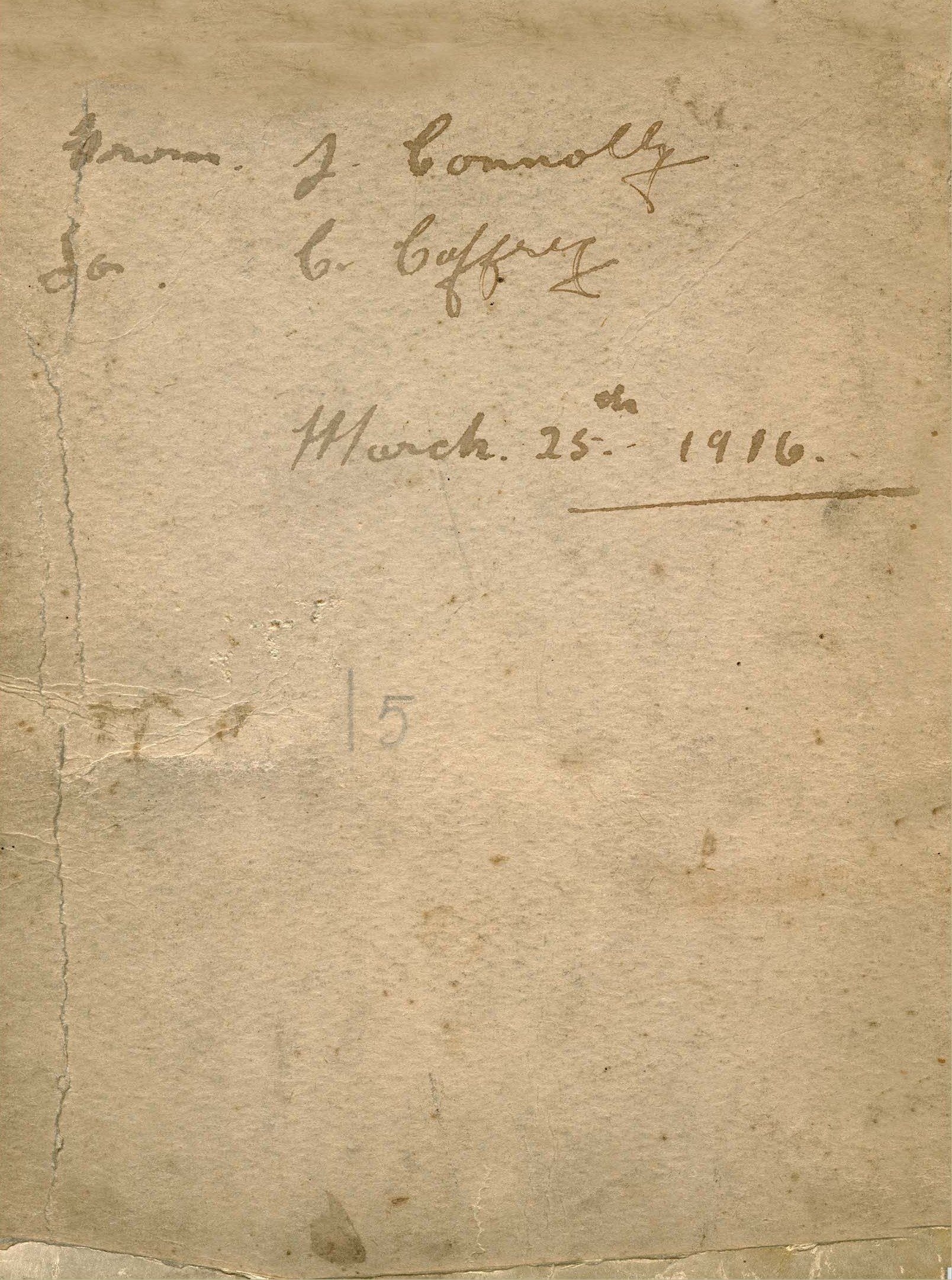

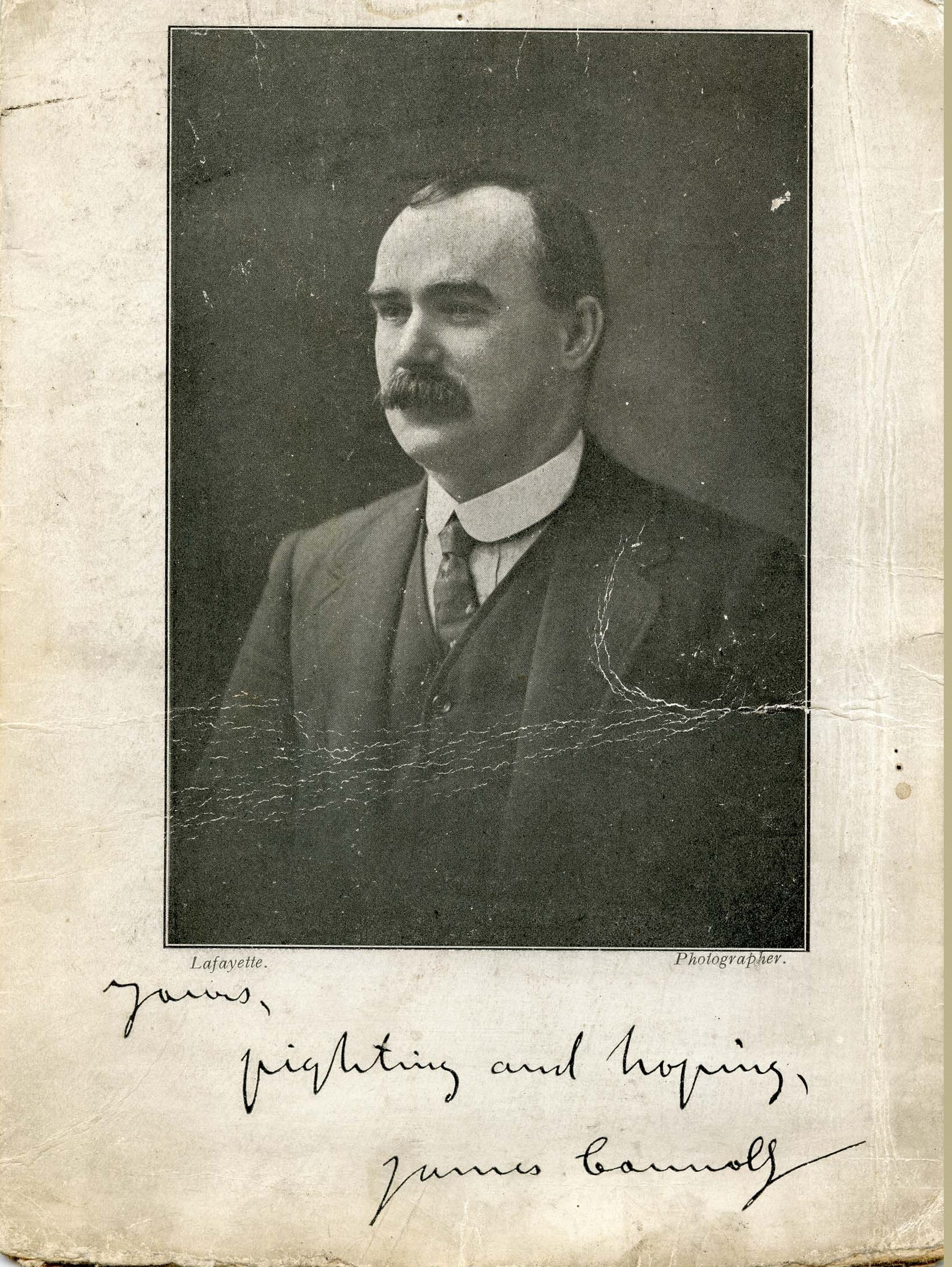

“Fighting and hoping” – James Connolly to Chris Caffrey , March 1916

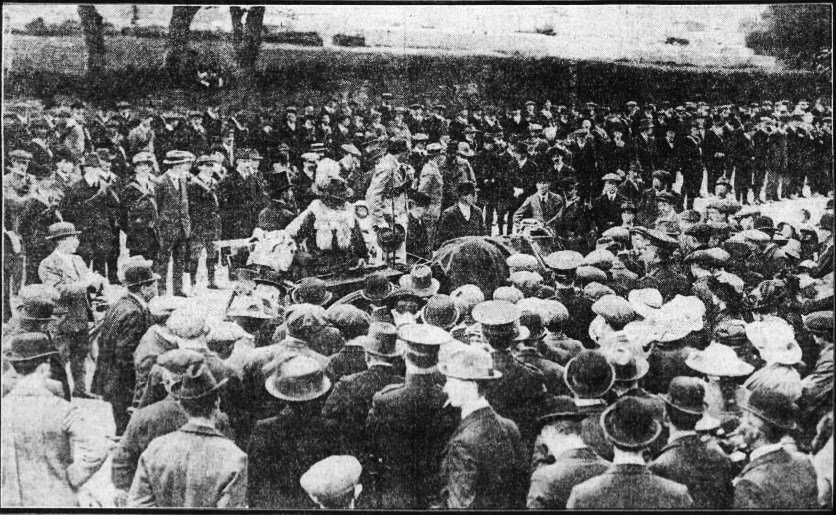

A fascinating piece of local and family memorabilia , with real historical significance . Signed “Yours , fighting and hoping , James Connolly” . The back of the photograph is really important , as it notes , “From J. Connolly , to C.Caffrey , March 25th , 1916″. This was of course just one month before the Easter Rising , in which both James Connolly and Christina Caffrey would participate.

A fascinating piece of local and family memorabilia , with real historical significance . Signed “Yours , fighting and hoping , James Connolly” . The back of the photograph is really important , as it notes , “From J. Connolly , to C.Caffrey , March 25th , 1916″. This was of course just one month before the Easter Rising , in which both James Connolly and Christina Caffrey would participate.

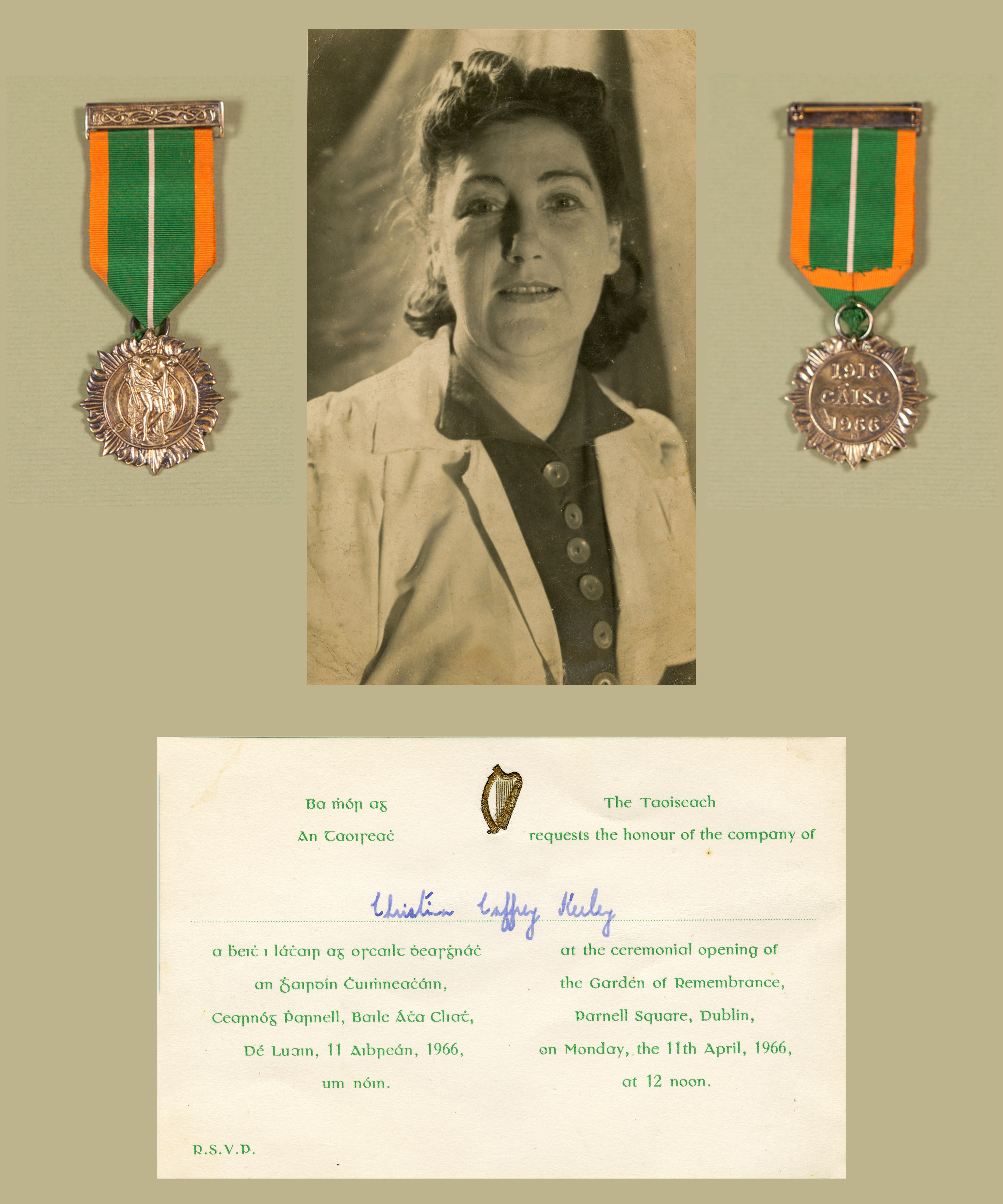

Christina Caffrey of Abercorn Road was a member of the Irish Citizen Army, and served at Stephens Green & College of Surgeons during the Rising. Throughout Easter week she travelled back and forward to the GPO headquarters carrying dispatches. On one occasion, when approached by a British soldier she started to eat the message and when challenged offered him a bag of peppermint sweets, and got waved on her way. During the War of Independence she smuggled weapons from Glasgow, where she met her husband to be James Keeley.

A family steeped in the radical tradition, her twin brothers and mother also engaged in revolutionary activity, while her sister Elizabeth was a founding member of the Irish Women Workers Union.

Some more wonderful material belonging to the Caffrey / Keeley family below , a photo of Christina in later years , her 1916 service medals and an invite to a commemoration event marking the 50th anniversary of the Rising in 1966.

It was an absolute honour for members of the East Wall History Group to join with Christina’s daughter Grainne , and her grand-daughter Anne this week when they proudly displayed their valued family items. The following photographs were taken this week at the Gibson Hotel (Point Village) , where a 1916 display was launched. The exhibition entitled “1916:THE UNTOLD STORIES’ OF THE DUBLIN DOCKLANDS” is a collaboration between the East Wall History Group and the Gibson hotel and can be viewed over the next month in the reception area , highlighting some local participants and events in the area.

-

If you have any comments , or wish to share your own family story , photo or memorabilia please contact us at :

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

Photo credits :

James Connolly note / Memorabilia : Courtesy Caffrey / Keeley family (Contact- East Wall History Group)

Wedding portrait : Caffrey – Keeley family / Gallery of Photography /

Gibson Hotel Launch: Shane O’Neill Photography