“Coining it” – Paydays and pilfering at the Docklands Bomb factory

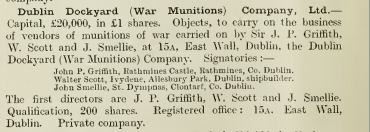

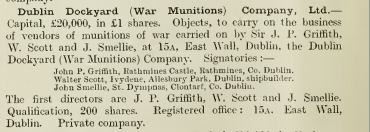

In 1915 munitions fever struck Ireland as the possibility of high paying jobs of £4-10 per week in English Factories presented themselves, coupled with the announcement that Ireland was to get its own munitions industry with National Shell Factories being established around the country. Similarly, Private Industry took up the challenge in the form of companies such as Hutton’s of Summerhill and Ashenhurst Williams of Store Street (manufacturing precision parts for bombs) and the Dublin Dockyard Company (which manufactured the actual shells themselves).

By May 1917 nearly 18,000 Irish people had emigrated to work in the English and Scottish Munitions Industry causing one Limerick Newspaper to comment that Irish people felt “money was to found on the floors of English Munitions Factories the way shells were found on the Irish seashore.”

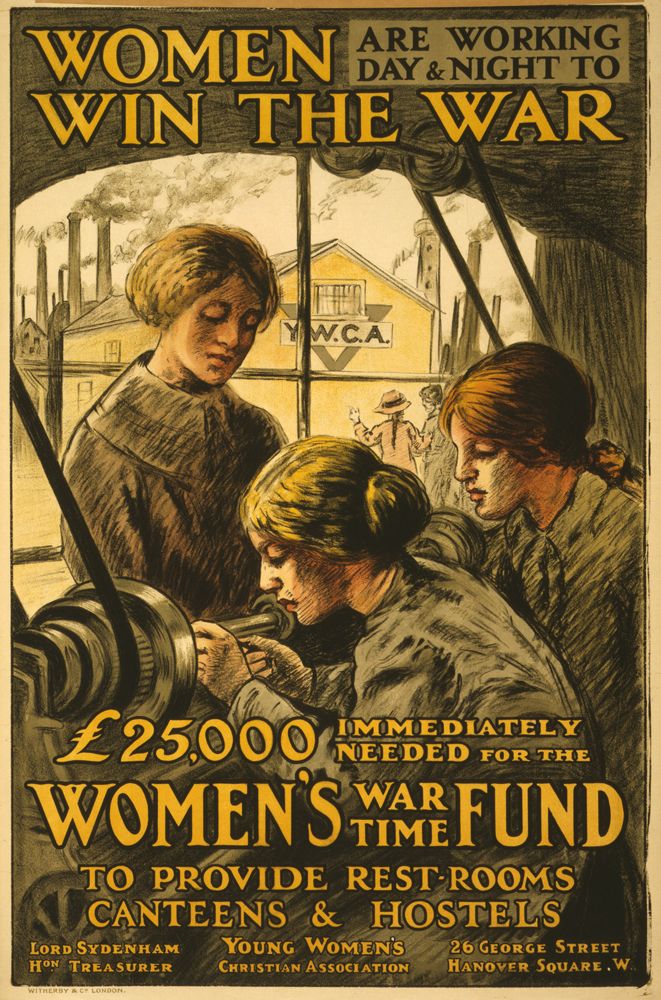

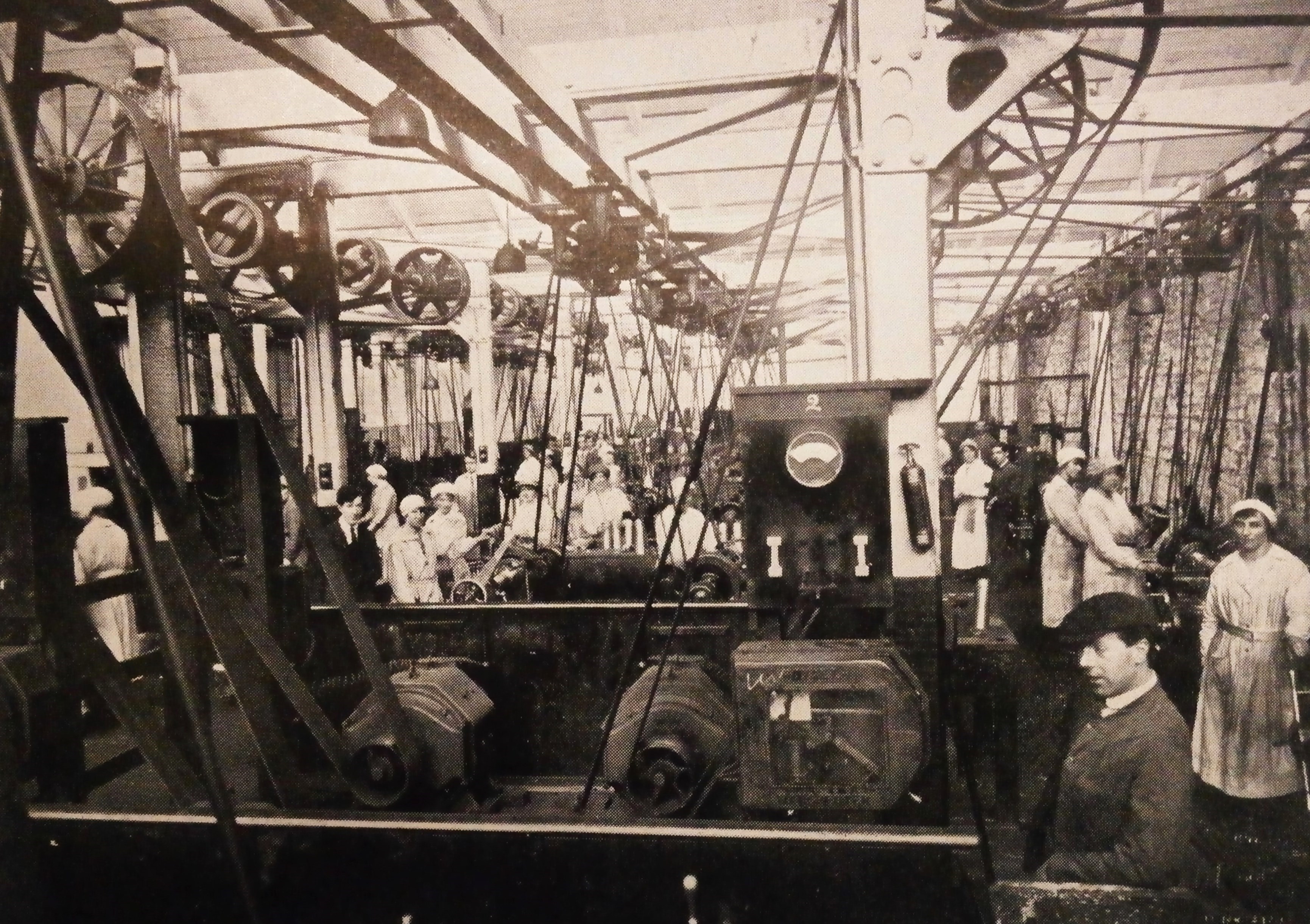

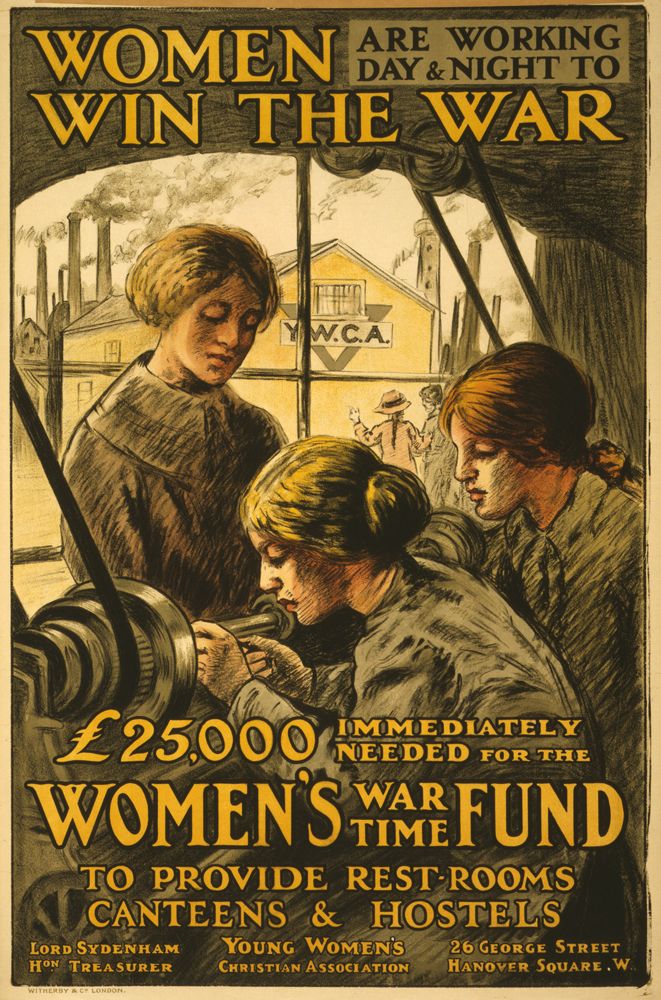

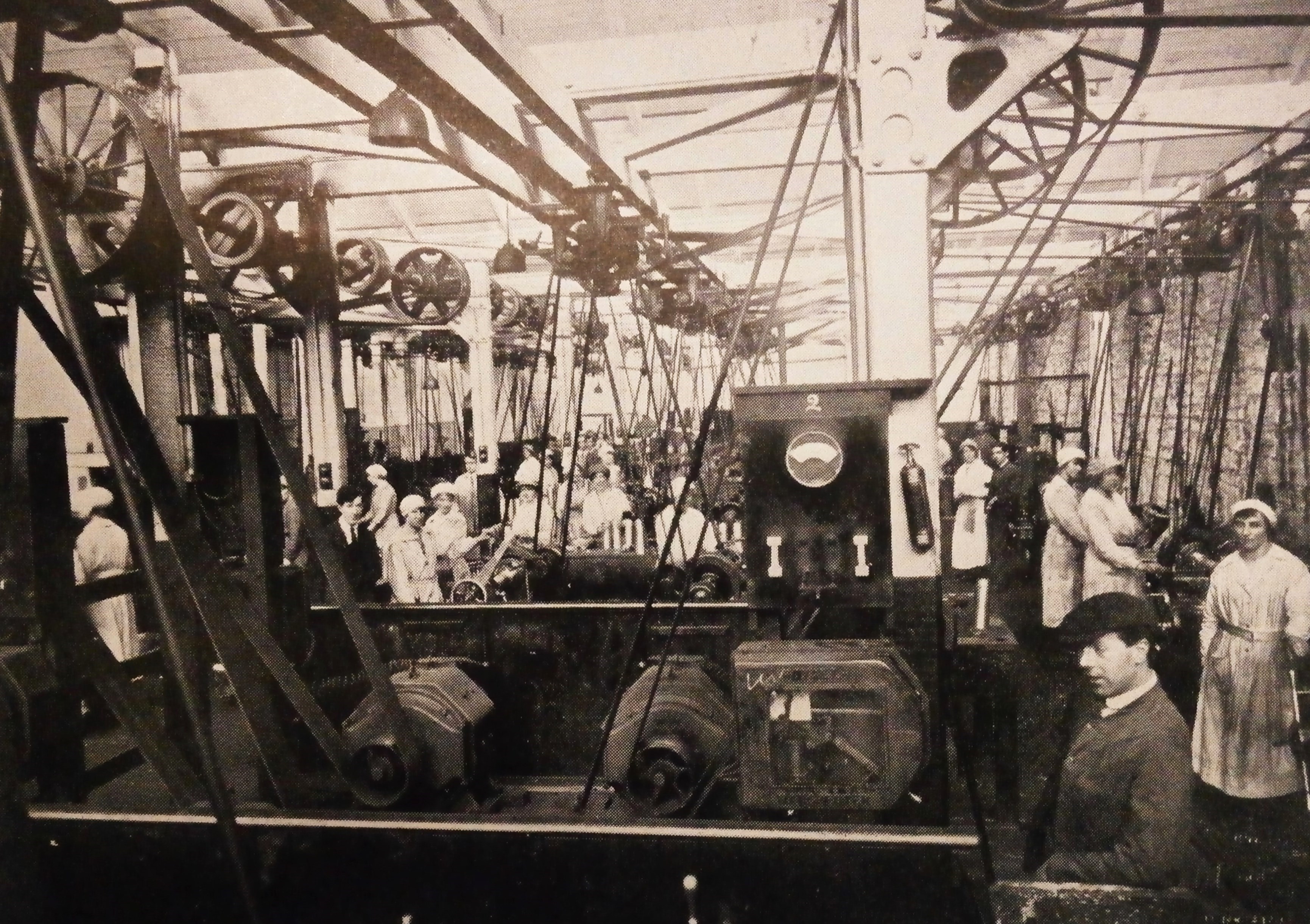

One young Dubliner seems to have felt that Irish Munitions Factories should present similar possibilities. Patrick Robinson was a 15 year old messenger-boy from the North Inner City. Robinson worked at the Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Factory which from 1916 produced 18 pounder shells throughout the First World War. 95% of the staff at the factory were women, due to an arrangement with the Amalgamated Society of Engineers called Dilution. Through this, women replaced men in the workplace thus freeing the men up to fight in France. Due to a successive number of agreements their pay was rather good with some of the girls making up to £2.10.0 per week. Sean O’Casey mentions a Dockyard munitions worker called Jessie Taite, “coinin’ it in”, who had over £200 in her Post Office saving account.

Young apprentices, on 4 shillings per day, could only look on envious, with the likes of messenger-boys and other unskilled laborers being left behind in their wake. The Dockyard was known for being an extremely good employer with few industrial problems from its establishment under Scottish born John Smellie in 1901. Ironically, strike action would escalate throughout the war years of 1916-18, almost exclusively involving apprentices, who due to the terms of their indentures, were prohibited from earning any of the big money on offer. These were unsuccessful. Smellie, having proved his point, would usually let them off with a warning and so they avoided the punitive financial penalties liable for illegal strike action during the war, often involving up to several months wages.

Robinson lived in Lower Gloucester Street with his widowed mother and sister. It’s likely that his meager pay had to stretch to support the family which would have put him under some pressure. Perhaps he found it humiliating to see girls, some the same age as himself, making a man’s wages. Whatever the reason, rather like the Limerick Newspaper suggested, he began to see the possibilities of all the scrap metal lying around the machines in the Dockyard Munitions Factory.

On the evening of the 27th July 1917, when coming off shift, James Bearsley, the Munitions Factory Foreman, noticed some suspicious bulges in young Robinson’s pockets. Searching him Bearsley found that they were copper bands used in attaching fuses to the 18 pounder artillery shells. Taking him to the factory Manager, Mr. Royce, Robinson confessed that he had taken similar rings before; he apologized, and then offered to pay the £2 he had received from a scrap dealer in Gloucester Place for the rings that he’d taken previously. Royce patiently explained to Robinson that it wasn’t that straight forward. All metal used for making artillery shells were supplied to the factory by the Ministry of Munitions and had to be accounted for. Scrap metal was charged for by the ministry as they could be sold at a profit and the Ministry was opposed to profiteering. However, these rings were not scrap, and directly affected the Factories production schedule. The factory was contracted for a specific number of shells each month. The fuses, and the copper bands which attached them to the shells, were made by separate contractors and supplied by the Ministry. An exact number, matching the Ministry’s order would have been supplied and without the full compliment of copper rings the factory would not be able to fulfill their order.

Under pressure, Robinson began to realise the full implications of what he’d done and agreed to co-operate. Shortly afterwards, Albert Siev, a 24 year old Polish born scrap-metal dealer at Gloucester Place, was arrested for receiving several consignments of stolen rings and prosecuted under the rather severe Defense of the Realm Act (DORA).

It’s probably worth noting that quite a number of Irish Citizen Army and Irish Volunteer members worked in the Dockyard, the Munitions Factory, and Dublin Port and things did “vanish” from time to time. It was something of a joke among Dockyard foremen, well into the 1950s that when tools and equipment went missing, they would usually explain it with “there must be another revolution coming soon.”

Having given evidence at Siev’s trial, Robinson avoided prosecution, and it seems may have even held onto his job. It may have seemed harsh to prosecute Sieve under the DORA Act but it was a serious matter and there may have been suspicions that they would ultimately end up in the wrong hands. Both Sieve and his young female assistant denied having ever seen Robinson in their shop.Whatever the authorities suspected they could not prove their case against Siev and he was dismissed on the 28th August. Two years later, while in business with his brother George, he was arrested for handling stolen bicycles, so it seems likely that his buying the copper rings was motivated by profit rather than any political ends.

If you have any clarifications, corrections or additional information please contact us. We are particularly anxious to hear from family members of women (or the small number of men) who were involved with the Munitions Industry. All contributions or assistance will be fully acknowledged and credited.

eastwallhistory@gmail.com

As part of the ‘Irish Women and the First World War’ series taking place at City Hall , Hugo McGuinness will be giving this talk next Tuesday 17th April in the Council Chamber ,City Hall, Dame Street .