“We declare that we desire our country to be ruled in accordance with the principles of Liberty, Equality, and Justice for all, which alone can secure permanence of Government in the willing adhesion of the people.”

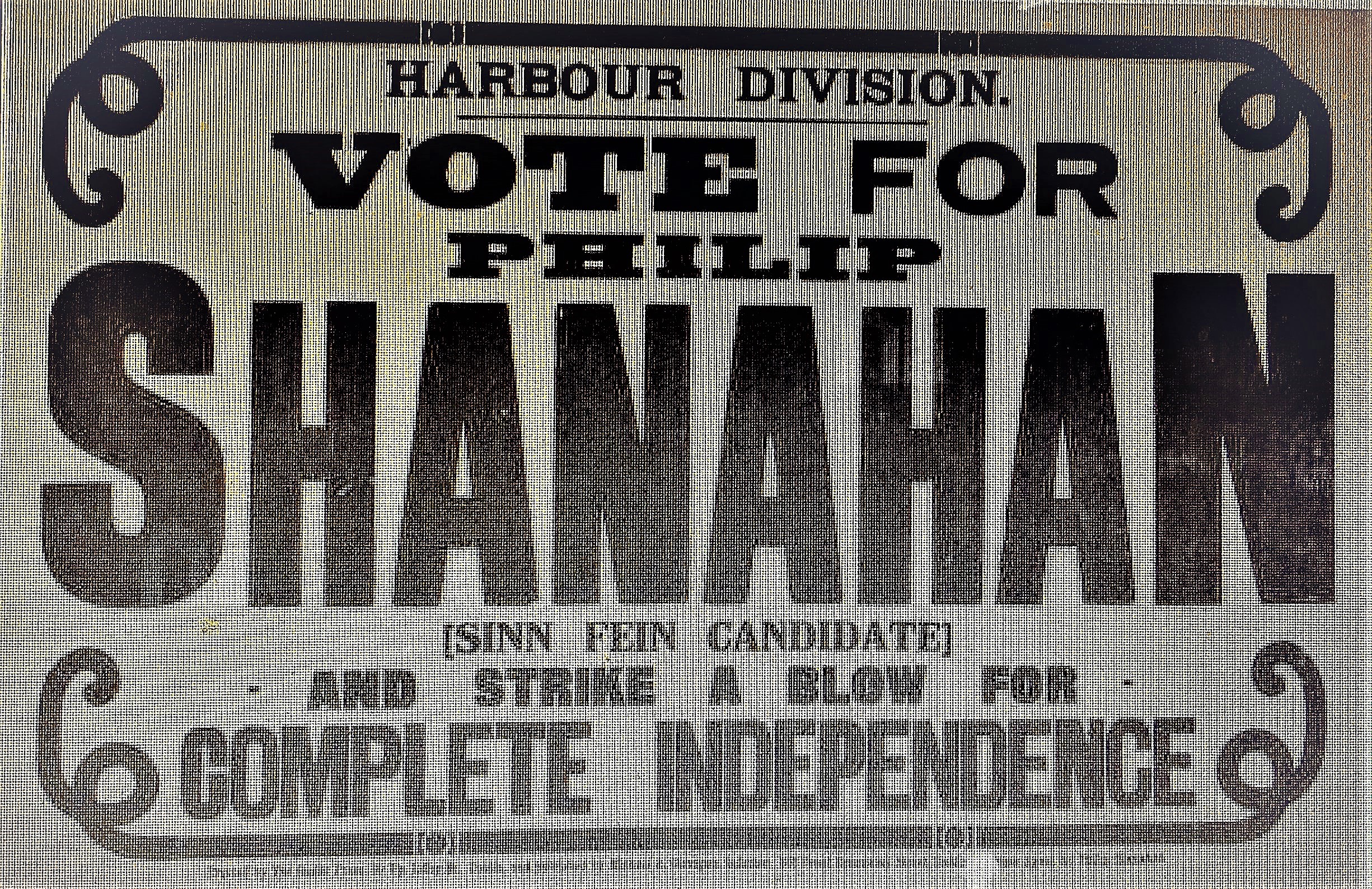

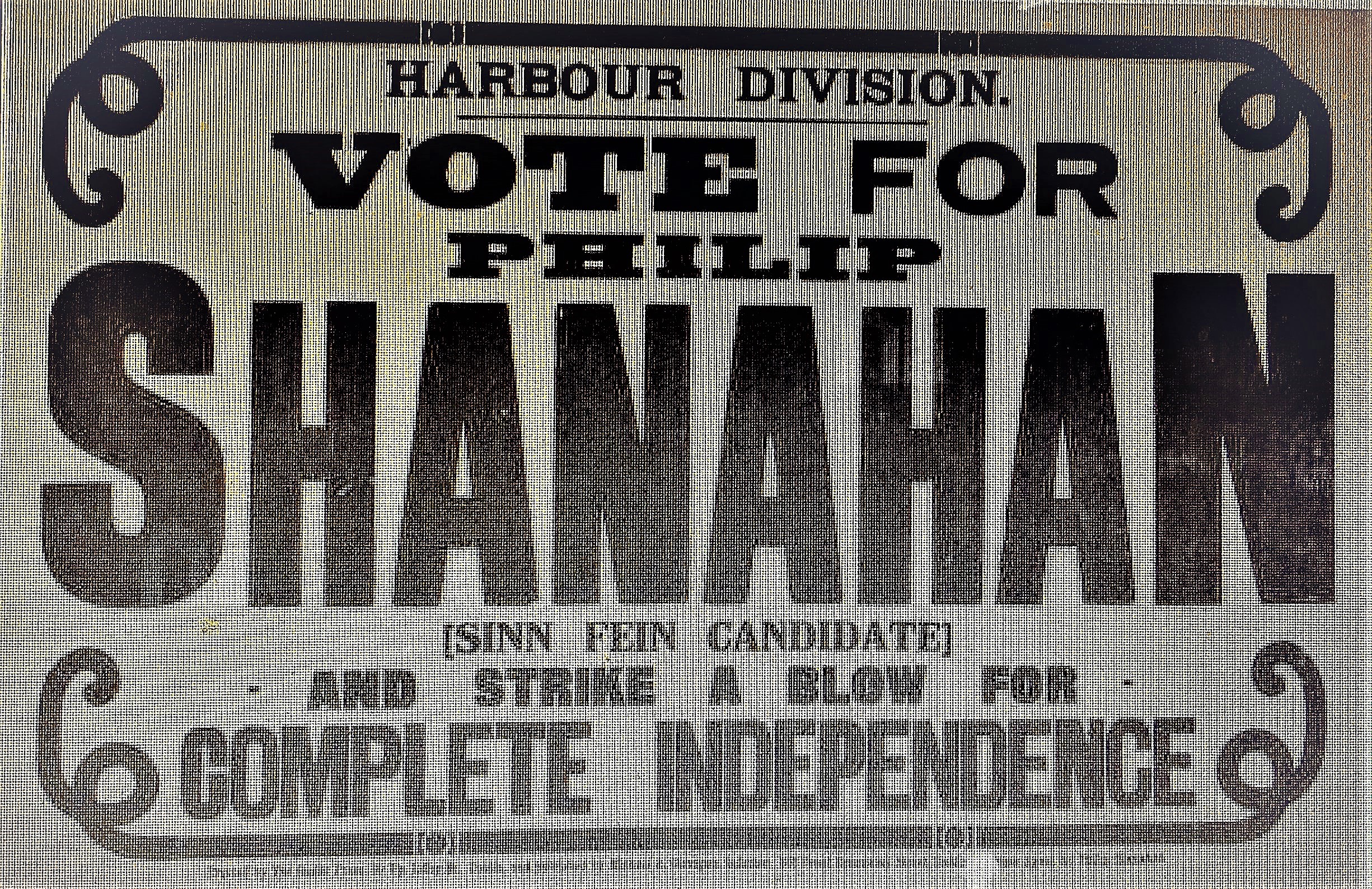

It was on the 21st January 1919 that the first Dáil Éireann assembled at the Mansion House, Dublin. The General election held in December of 1918 had been a landslide victory for Sinn Féin and an overwhelming endorsement of the ‘Irish Republic’. As per their election manifesto, those elected refused to take their seats as Members of Parliament in Westminster and established a parallel body, Dáil Éireann in defiance of British rule in Ireland. The TD elected for this area (the Harbour Division) was Phil Shanahan, who took his place in the revolutionary assembly a century ago today.

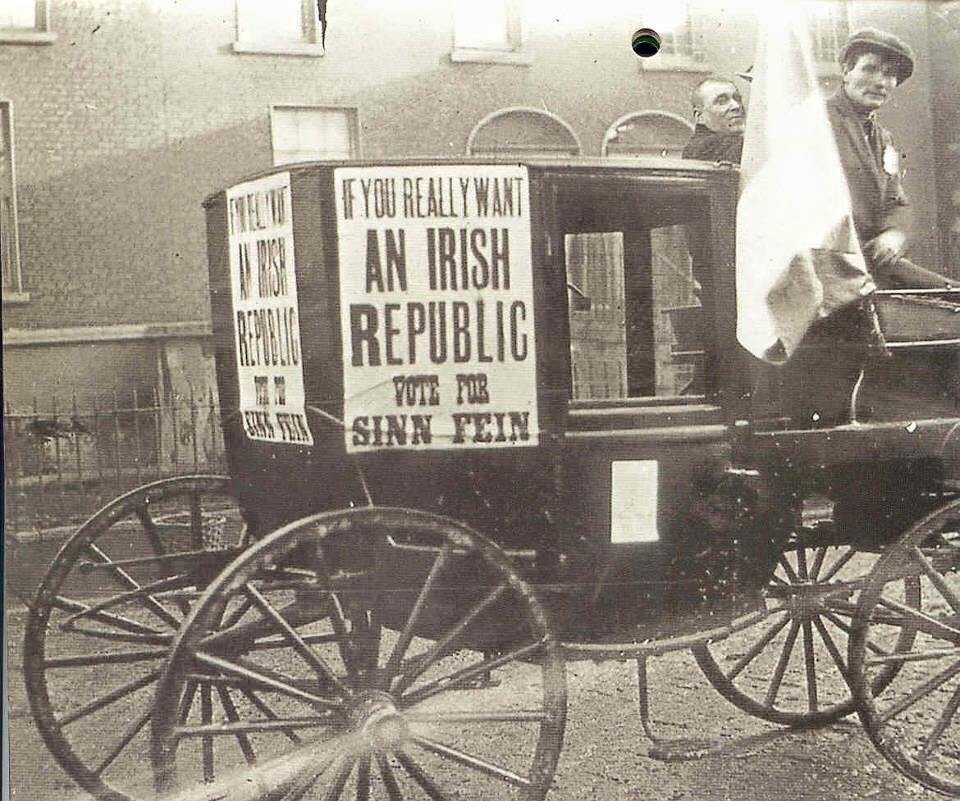

The General election called for Great Britain & Ireland had been the first held since 1910. It was long overdue, postponed due to the Great War. In the intervening period of course, the Easter Rising had taken place and an Irish Republic declared by force of arms. This election was going to be different – united under the banner of the Sinn Féin party, Republican candidates pledged themselves to abstain from the Westminster Parliament. All the candidates chosen to represent Sinn Féin had been ‘out’ in 1916, with Phil Shanahan standing in the Harbour Division. This area included East Wall, North Wall, North Strand and other parts of the North Inner City.

Phil Shanahan was a publican, operating a premise at Foley Street, in the heart of the infamous ‘Monto’. Originally from Tipperary, Shanahan had been at the Jacobs garrison in Easter Week 1916, a member of the Irish Volunteers. He was jailed after the surrender and was among the 1,800 men interned at the Frongoch camp in Wales. His involvement with the insurrection created difficulties for the publican, and Timothy Healy (politician and barrister) noted:

“I had with me to-day a solicitor with his client, a Dublin publican named Phil Shanahan, whose licence is being opposed, and whose house was closed by the military because he was in Jacob’s during Easter week. I was astonished at the type of man – about 40 years of age, jolly and respectable. He said he “rose out” to have a “crack at the English” and seemed not at all concerned at the question of success or failure. He was a Tipperary hurler in the old days. For such a man to join the Rebellion and sacrifice the splendid trade he enjoyed makes one think there are disinterested Nationalists to be found. I thought a publican was the last man in the world to join a Rising.”

The main rival candidate to Shanahan was Alfie Byrne, North Wall born and a well-known politician and publican, with a premise on Talbot Street. Though he would go on to enjoy a record-breaking ten terms as Lord Mayor, Byrne was at that time a hate figure for Republicans and Trade Unionists in the area, with Jim Larkin having held a particular dislike for him.

Many of those who campaigned for Phil Shanahan were local activists. One of these was Tom Leahy, shipyard worker, trade unionist and 1916 veteran. Leahy had served at Annesley Bridge, Ballybough and the GPO garrison as a member of the Irish Volunteers, but on his return from internment joined the Citizen Army and was active in the Docklands area. He recalled:

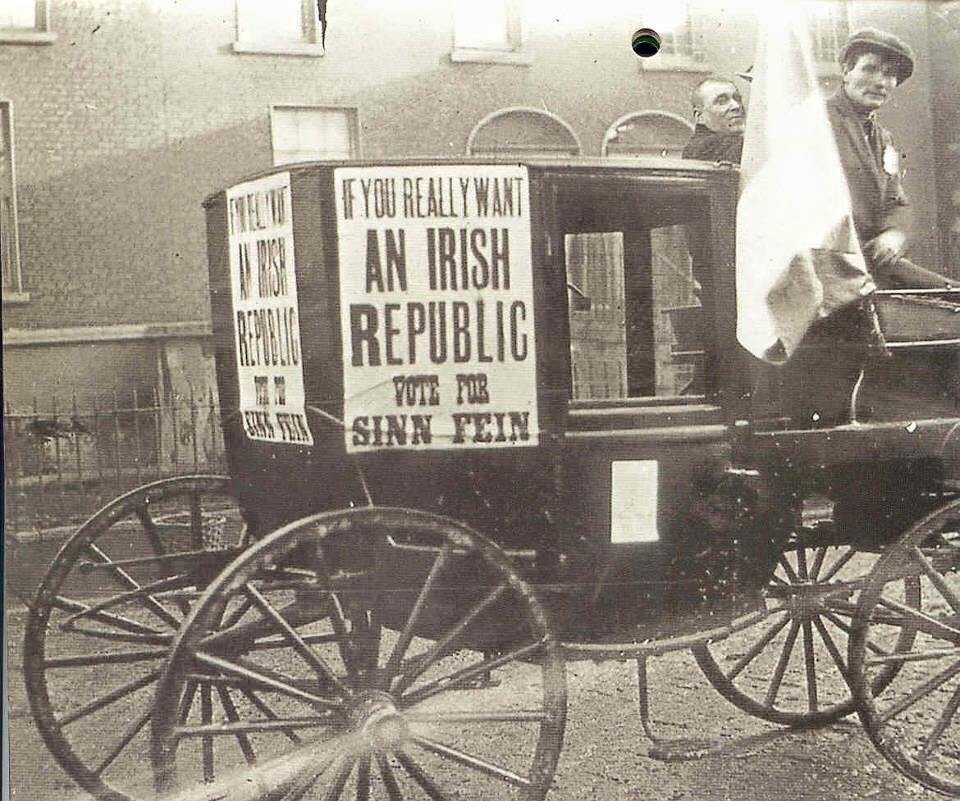

“When the general election was declared to take place, our committee got into working order and a finer crowd of willing workers was hard to equal. Jim Lawless was Director of Election in the North Dock. While canvassing in the slums it was awful to behold where human beings had to sleep, eat and drink. No wonder the working classes were always ripe for revolt against their conditions. However, our work had its reward, for Phil, of course, won the seat, the first and last time from Alfie, who still holds it in the Dáil. He fought very hard to retain it at that time. During one of our meetings down the Church Road, in East Wall, we met with a very hostile crowd who were mostly all Scotch people working in the Dockyard, and the followers of Alfie were also strong there. When I rose to open the meeting and to introduce Sean T. O’Kelly and Jim Lawless, also Phil Shanahan, we were met with a shower of sods and Union Jack Flags waving all around us, but it did not last long, as the precaution was taken beforehand for this, and a company of 2nd Battalion Volunteers were near at hand and, with batons, cleared the place of the objectors in quick time. We were allowed to hold our meeting without interruption after that. After the election was over and results known there was great rejoicing in the North Wall camp and a great blow to Alfie Byrne and his followers.”

These newspaper reports from December 1918 illustrate how passionately voters in the Harbour Division supported the republican candidate:

“Dublin Dockyard workers also made a rather striking demonstration. Immediately they knocked off work at 1.30 they assembled outside the shipyard, and headed by the O’Toole pipers, they marched to Marlborough St. polling station (Harbour Division), and every one of the 300 of them displayed the Shanahan badge. They carried a banner, on which was inscribed- ‘Shipyard workers want freedom- not slavery’. They were enthusiastically greeted.”

Another incident was described when: “A body of workers marched to a booth bearing a scroll with the legend ‘We won’t vote for Byrne’. The great majority of women voters in some districts were openly S.F.”

This was of course the first occasion where women could not only vote but also could contest an election. Two women were chosen to stand for Sinn Féin, Countess Markievicz successfully in a Dublin constituency and Winifred Carney unsuccessfully in Belfast. The total electorate of the Harbour constituency was just over nineteen and a half thousand potential voters, consisting of 11,763 men and 7,757 women. There was a 67% turnout on December 14th.

The Alfie Byrne camp could obviously sense his defeat was a real possibility and seemed to engage in deliberate petty harassment at the polling station. At least one man was identified by them as an impersonator, arrested but afterwards released with no charge. Even the candidate himself was not spared:

“The S.F. organisation was best in the Harbour Division, and cars with their colours were everywhere busy…. When Mr. P Shanahan (S.F.) went to vote for himself he was objected to and had to be sworn before voting”.

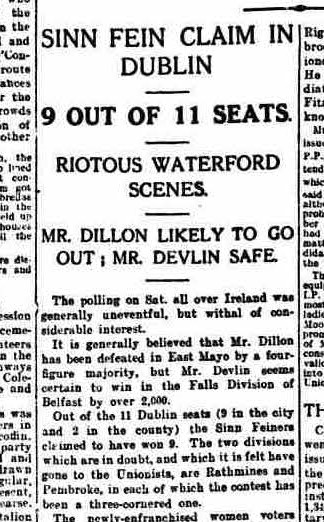

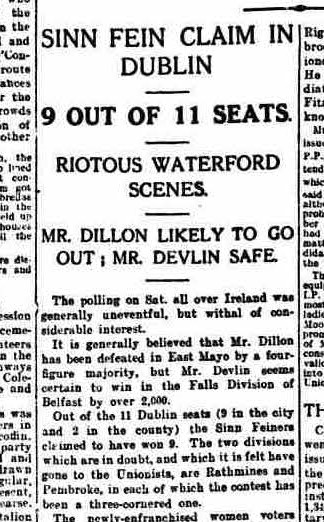

Shanahan defeated Byrne by 7,708 votes to 5,386. In Dublin the SF party returned 9 of the 11 available seats, losing only in strongly unionist constituencies of Rathmines and Pembroke. Nationally, they won 73 of the 105 seats, consigning the Irish Parliamentary Party to the history books and receiving an endorsement for the pursuit of an Irish Republic.

As per the commitment in their manifesto , none of the victorious SF candidates would take their seats at the Westminster Parliament .Early in the new year those elected took this oath - ”I hereby pledge myself to work for the establishment of an independent Irish republic; that I will accept nothing less than complete separation from England in settlement of Ireland’s claims; and that I will abstain from attending the English Parliament” and on 21st January 1919 first Dáil Éireann was convened at the Mansion House , Dublin.

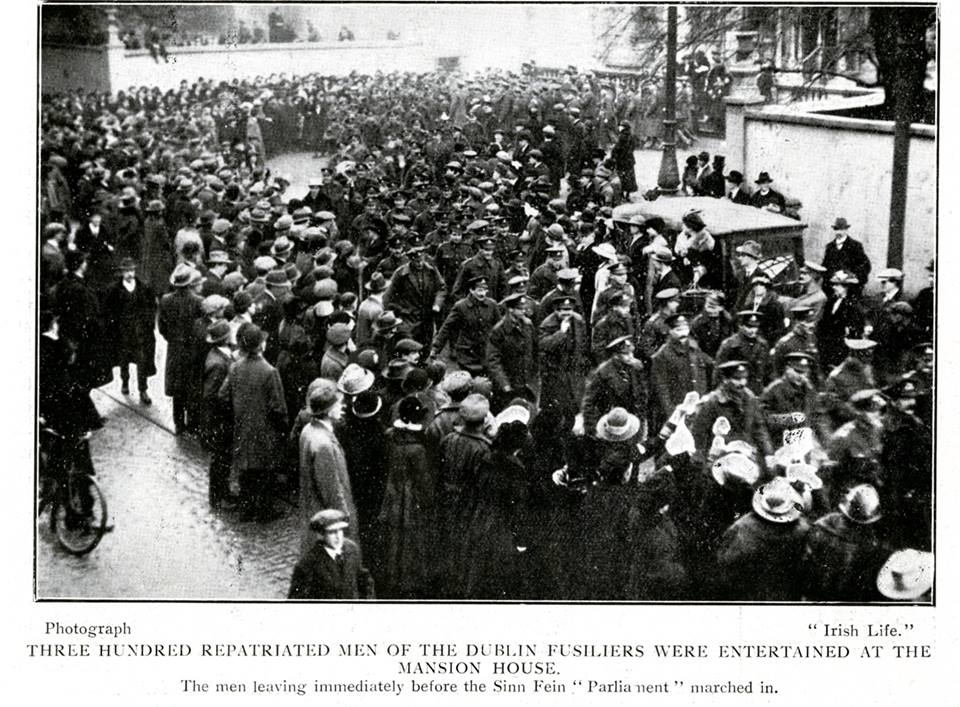

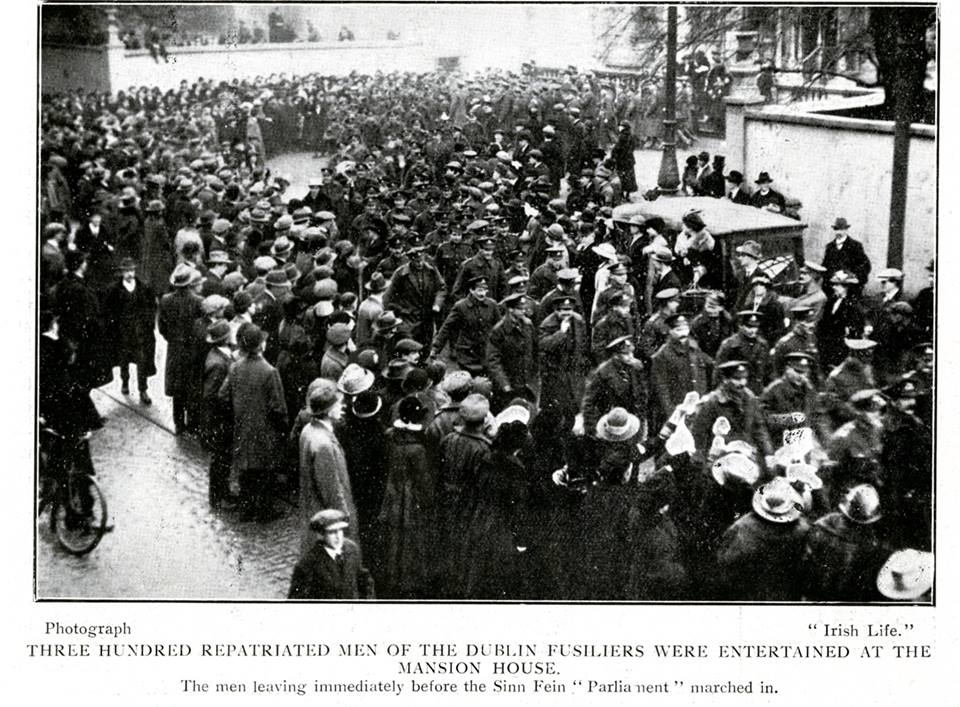

There was a slightly surreal scene on the afternoon of this first historic meeting, as recorded by the Irish Times:

“It was the first meeting of the Constituent Assembly summoned by the Sinn Fein Party. By a striking coincidence, the Mansion House was on the same day the scene of another and very different assembly, called for the purpose of according a public reception to the gallant soldiers of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers who have been prisoners of war in Germany.

A city trader who was an interested spectator at the departure of the cheering soldiers and the arrival of the first of the Sinn Feiners in Dawson street made the comment on the scene: ‘No city in Europe can beat Dublin after all’ – which evoked a hearty laugh from the bystanders.”

Photo taken at second session of Dáil Éireann , Phil Shanahan in back row.

Though invited, the small number of successful Irish Parliamentary Party members nor the 26 Unionist representatives chose to attend. Less than half of the Sinn Féin TD’s were present, with the roll call for the day listing many as ‘fé ghlas ag Gallaibh’ (Imprisoned by the foreign enemy). This included Countess Markievicz, Eamonn DeValera and Arthur Griffith. Phil Shanahan TD was among those in attendance, accompanied by many of those who helped elect him, as recalled by Thomas Leahy:

“Later on, when the members of the First Dail, who were not in prison, met for their first public session to form their government in the Mansion House, I attended with Phil Shanahan, Jim Lawless, Peadar Carney, Tom Slator and a few others I cannot remember… I can still see that day as it took place before the world and looking around then, I wondered what people were thinking -was it about Easter Week and the glorious deed”.

The business of the first Dáil Éireann was conducted entirely in the Irish language, and the order of business comprised of the reading of the Constitution of the Dáil, the Declaration of Irish Independence, the Democratic Programme and a Message to the Free Nations of the World. This called upon every free nation to uphold Ireland’s “national claim to complete independence as an Irish Republic – against the arrogant pretensions of England founded in fraud and sustained only by an overwhelming military occupation”.

A more complete assembly of Dáil Éireann in April 1919 , Phil Shanahan again in back row.

In addition to the events taking place in Dublin on 21st January 1919 another group of men with the Irish Republic as their goal were busy. In Soloheadbeg, County Tipperary volunteers of the Irish Republican Army ambushed members of the Royal Irish Constabulary, shooting two dead and capturing their weapons and a consignment of explosives they were transporting. This was regarded the opening confrontation of the Anglo-Irish war (or War of Independence) which would continue until the truce in July of 1921. What followed was a period in which the political and military campaigns often overlapped, and Phil Shanahan TD was also part of the war effort.

Shanahans Public House in Foley Street was a well-known meeting point for republican activists, and a clearing house (of sorts) for captured, stolen or purchased weapons. The fact that it was at the centre of one of the largest red-light districts in Europe helped, and many a British soldier or auxillary frequenting the area was relieved of his firearms, which ended up passing through Shanahans. Not all weapons were passed over involuntarily, as one republican recalled

“We procured quite a large number of arms by purchasing them from British military. A lot of British soldiers used to frequent Phil Shanahan’s public house and it was there most of the contacts were made.”

Quite a few memoirs by Republican activists from this era mention this activity. Thomas Leahy recalls this (and mentions also the famous footballer, pigeon racer and East Wall resident ‘Cocker’ Dalys role):

“Several British naval vessels came to the Dockyard for repairs as the firm was on the Government list for such and several raids were made on these vessels for arms when most of the crew were ashore. Any other ships we thought had arms were searched also. One man named Pat Daly was very daring in that line. He was over 6 ft. in height and very strong, and many a rifle and ammunition was brought to Phil Shanahan’s shop in Foley St.”

According to the North Inner-City Folklore project:

“During the War of Independence his pub in Foley Street was a meeting place for many top-ranking IRA men including Michael Collins who was a frequent visitor. The legendary ‘Big Four’ – Sean Treacy, Dan Breen, Sean Hogan and Seamus Robinson often stayed in the upstairs rooms over the pub. Men on the run from British from all parts of the Country came to Phil’s pub. Many important meetings were held in the upstairs rooms while local newsboys organised by Shanahan for intelligence purposes kept watch in the immediate vicinity for British troops and Black and Tans.”

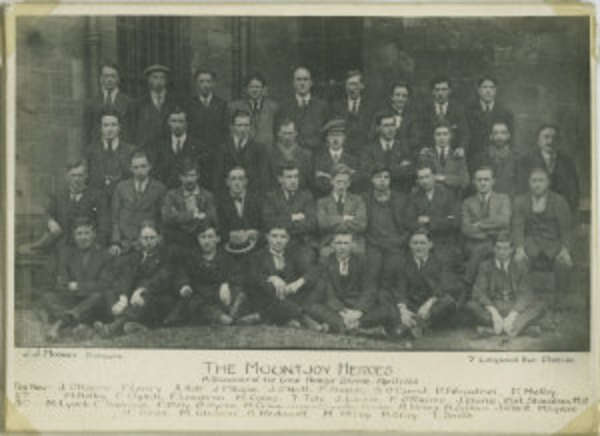

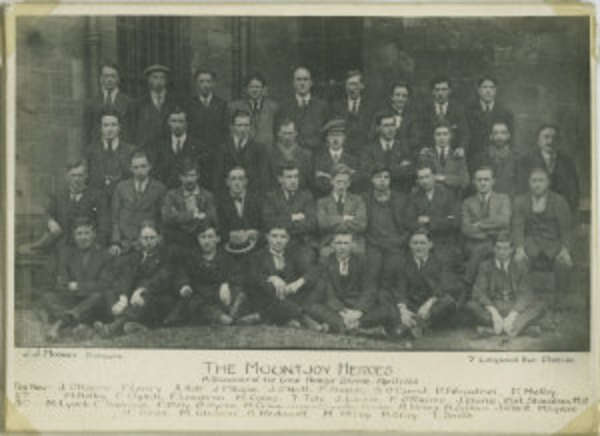

A large group of 1920 Mountjoy hunger strikers , including Phil Shanahan.

In April of 1920 Shanahan was arrested and detained at Mountjoy prison, were he joined in a mass hunger strike demanding the return of political status for republican prisoners. In May of 1921 he was again elected, again abstaining from the Westminster Parliament and joining 125 Sinn Fein TD’s in the second Dáil. In 1922 he failed to get elected – he stood as an anti-treaty candidate , in an election which nationally saw Sinn Fein split allegiances ( with 58 elected as pro treaty and 36 as anti-treaty) and Alfie Byrne also returned.

According to the North Inner-City folklore project, the pub finally closed in 1927. Shanahan was in poor health and was confined to bed in a room above the pub. The local were aware of his generosity and continued to bring him food to sustain him. When news of his condition reached friends, they arrived at the boarded-up pub, and moved him to a lodging house at North Frederick Street owned by a Mrs Breen. When his condition improved, he returned to his hometown Hollyford in County Tipperary. He died a few years afterwards in 1931, aged 57 years old.

In the 1950’s one of the new flat blocks in Sheriff Street was named Phil Shanahan House in his honour. This has since been demolished. In 2014 the North Inner-City Folklore Project erected a plaque at the location where his public house once stood.

Phil Shanahan (1874 to 1931)

Phil Shanahan in uniform (Image source: Tom Shanahan)

On this day, 21 January 2019, which marks the centenary of the first Dáil Éireann we remember these words from the Democratic Programme, as presented on that historic occasion:

“It shall be the first duty of the Government of the Republic to make provision for the physical, mental and spiritual well-being of the children, to secure that no child shall suffer hunger or cold from lack of food, clothing, or shelter, but that all shall be provided with the means and facilities requisite for their proper education and training as Citizens of a Free and Gaelic Ireland.”

For corrections , clarification , further information and to provide additional images contact :

eastwallhistory@gmail.com