“Tell every man that you do not understand liberty for the white man, and slavery for the black man; that you are for liberty for all, of every color , creed and country”

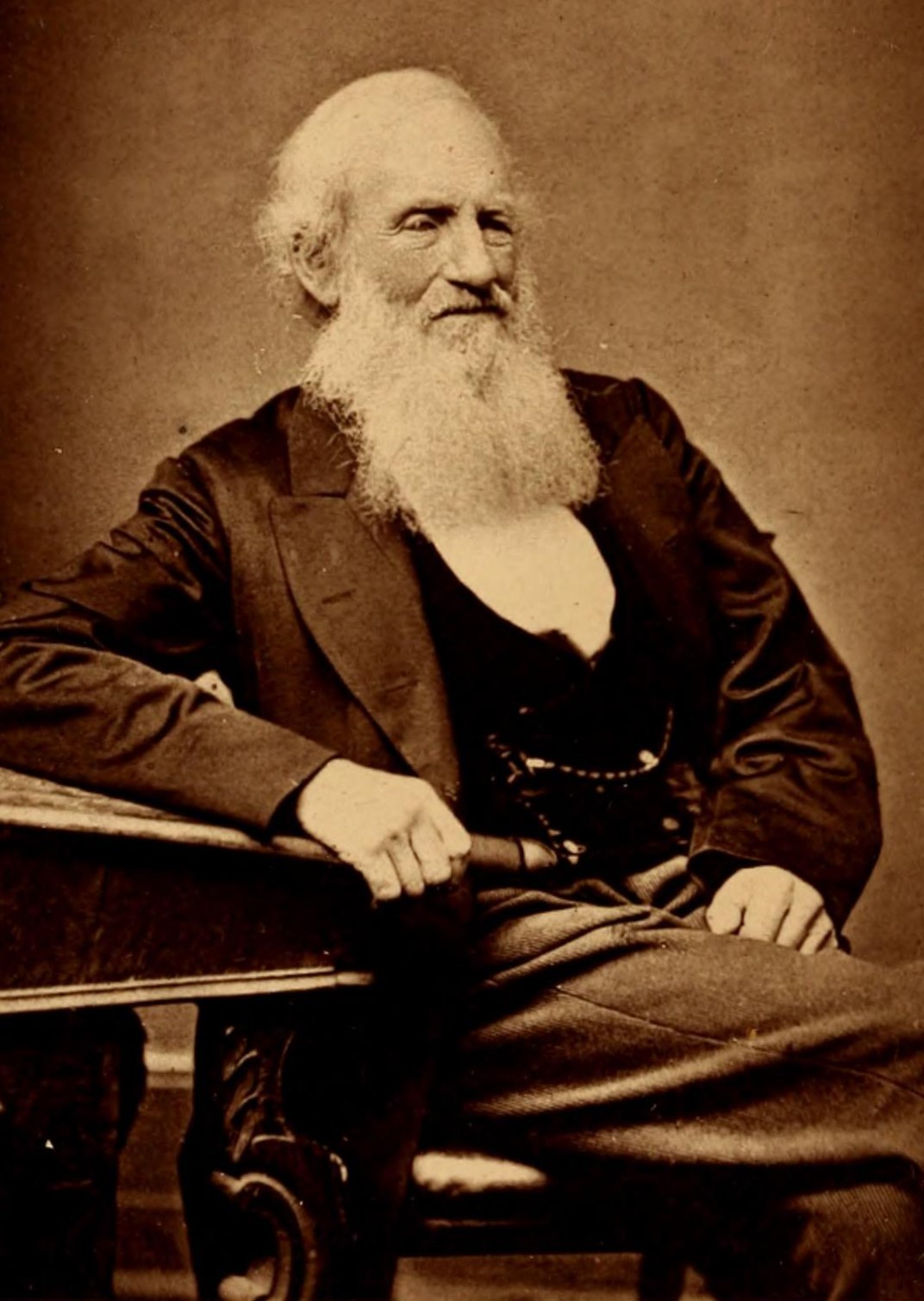

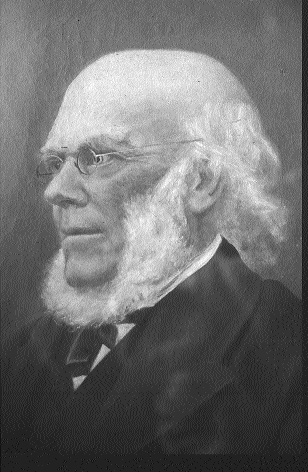

Richard Allen was born in 1803 at Harold’s Cross, which was then a rural area of Dublin. The family were part of the Society of Friends (Quakers) community in the City. His father, Edward Allen was a successful Linen merchant, and as part of his charitable and philanthropic works (as often associated with Quakers) he was a founder of the Fever Hospital in Cork Street. Edward and Ellen Allen lived at James Street and afterwards at Bridge Street. The property at Harold’s Cross was their summer residence, this being largely countryside at the time. They had a total of 15 children, with Richard being the second.

Like most his sisters and brothers he was educated privately by a tutor, and aged 17 he became involved with the family business. In 1828 he married Anne Webb, a member of another successful Quaker business dynasty. He developed his own business, and operated from premises on Sackville Street and also Patricks Street in Cork. The building on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) was destroyed in the fires that devastated the thoroughfare during the 1916 Rising.

Amongst his friends and wider circle of associates he would include Frederick Douglass, the American publisher William Lloyd Garrison, the temperance campaigner Father Theobald Mathew, the Dublin-born philanthropist Dr Barnardo, and the poet and balladeer Thomas Moore.

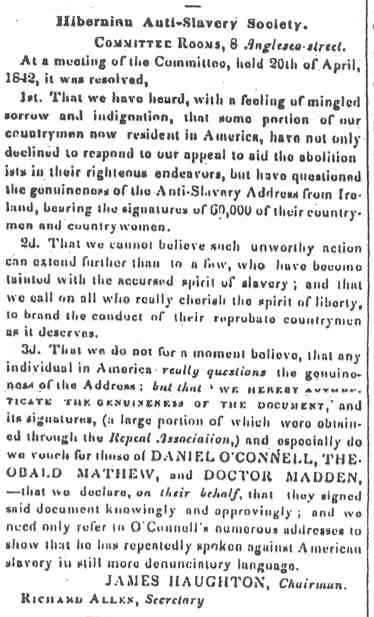

Richard Allen’s commitment to social reform saw him embrace the temperance movement, a campaign for prison reform and abolition of the death penalty, and most significantly the anti slavery cause. In 1836, alongside two fellow successful Quaker businessmen Richard D. Webb (printer & publisher) and John Haughton (corn merchant) he founded the Hibernian Anti Slavery Society. Haughton was chairman while Allen became its secretary.

The Society was considered by its contemporaries as “the most ardent in Europe in its antislavery efforts and activities.” One of the chief goals of the Society was to “put an end to the unholy alliance between Irishmen and slaveholders in America.”

The Dublin Ladies’ Association, auxiliary to the Hibernian Anti-slavery Society was also established. As one modern writer commented:

“…the Ladies Associations existed as independent auxiliary bodies to the Hibernian Anti-Slavery Society, holding their own meetings, organizing fund-raisers, liaising with the female wing of the American society and perhaps most importantly producing their own texts.”

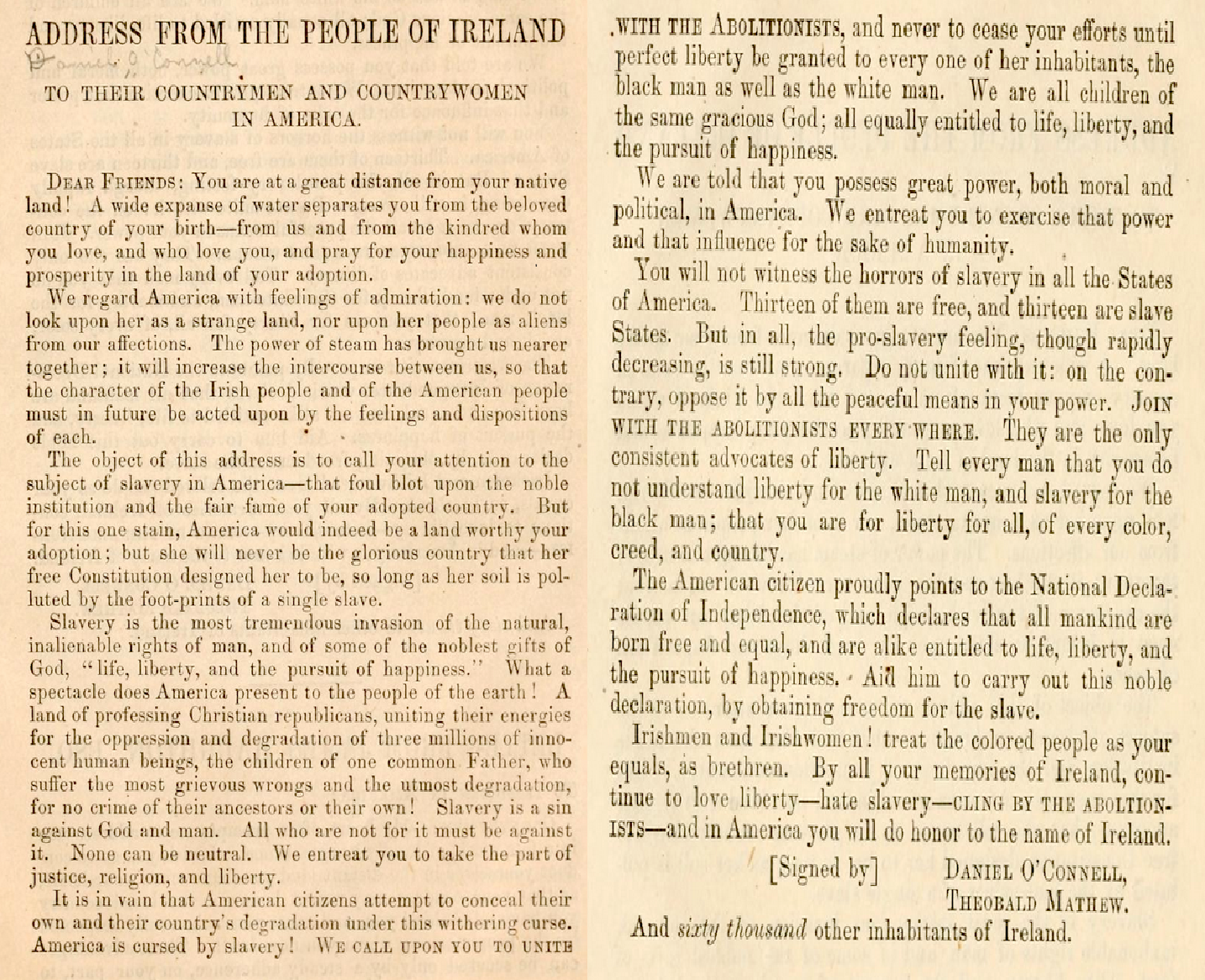

One of the most significant acts of the society was the production of a declaration calling on the Irish in America to “UNITE WITH THE ABOLITIONISTS.”

In 1840 Allen and Webb were among the attendees of the World Anti Slavery Convention in London, the first of its kind ever held. It was an event immortalised in a painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon. Incredibly detailed, Richard Allen, Richard Webb and Daniel O’Connell can be identified clearly in this historic work of art, now on display at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

There were approximately 600 delegates present, with 17 from Ireland, representing Dublin, Cork and Belfast. Those present “included 20 members of the British Parliament, 100 clergymen of all denominations, and deputations from France, Spain, Switzerland, Canada and the United States and West Indies.”

The Dublin published newspaper The Freemans Journal reported the assembly as including “ the sooty African, the swarthy coloured man, the intrepid American abolitionist, the indefatigable West India missionary , accompanied by two newly-emancipated negroes, whose language, whose deportment, whose bearing show that they value liberty, and that they thirst to extend to others what they themselves received.”

The convention was not without some controversy, after a row broke out over whether women could be admitted as full delegates, which led to a series of splits in the ranks. This was not unusual, as within the broader abolitionist movement some sections were seen as too radical due to their promotion of women’s equality, women’s suffrage and workers rights. The Hibernian Anti Slavery Society adopted the more progressive position that women should be admitted. The convention opted not to act contrary to ‘English custom’ and women could only observe from a designated gallery. This was despite a number travelling a far distance to participate. This outcome was criticised by James Mott, a leading U.S. abolitionist (and Quaker) whose wife had also come to London:

“One of the first acts of a Convention , assembled for promoting the cause of liberty and freedom universally, was a vote, the spirit and object of which was a determination that the chains should not be broken, with which an oppressive custom has so bound the mind of women”.

Daniel O’Connell was widely regarded as one of the most impressive figures in attendance, and after he spoke a New York State abolitionist, James Canning Fuller appealed passionately to him as he believed he “…could do more to pull down slavery in America than any other individual. To the Americans, there was a particular charm about Mr O’Connell’s name, and his influence in that country was greater than that of the whole convention. If Mr O’Connell would issue an address to his countrymen in America the effect would be felt throughout the length and breadth of the land”.

The Hibernian Anti Slavery Society undertook this task and did issue such an appeal, with Daniel O’Connell the first of the sixty thousand signatures gathered in support. There was great enthusiasm shown for the pledge, as one contemporary report illustrates:

“A young lad, about thirteen, had been most indefatigable in collecting signatures. I heard the other day, he was going from house to house in the more genteel neighbourhoods, rapping at hall doors. . . the other day he came for five sheets more. He told me he was going to school the next week, and that before he left, he must do all he could to liberate the slaves.”

The ‘Address from the People of Ireland To Their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America’ was written by James Haughton, Richard Allen and Richard Davis Webb and was immediately endorsed by O’Connell. He used the membership of his Repeal Association, (dedicated to the repeal of the Union between Britain and Ireland), to gather a reported 60,000 supporting signatures. The ‘Address’ was brought to America by the black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond (following a tour of Ireland), where abolitionists led by William Lloyd Garrison orchestrated its public reading in Boston. The Address explicitly condemned American slavery and called on all the Irish in America to ‘treat the colored people as your equals, as brethren’. Irish immigrants were also ordered ‘TO UNITE WITH THE ABOLITIONISTS’ and that ‘Slavery is a sin against God and man. All who are not for it must be against it. None can be neutral.’

Disappointingly, the address did not have the desired effect. Two decades later, in a letter to Richard Allen, a leading American abolitionist lamented:

“It is horrible to think that so large a mass of your countrymen, who have known what it is to suffer from oppression, and who have torn themselves away from their native shores, in order to find freedom in this land of boasted liberty, should be enlisted in support of the most horrible system of slavery that the earth has ever known.”

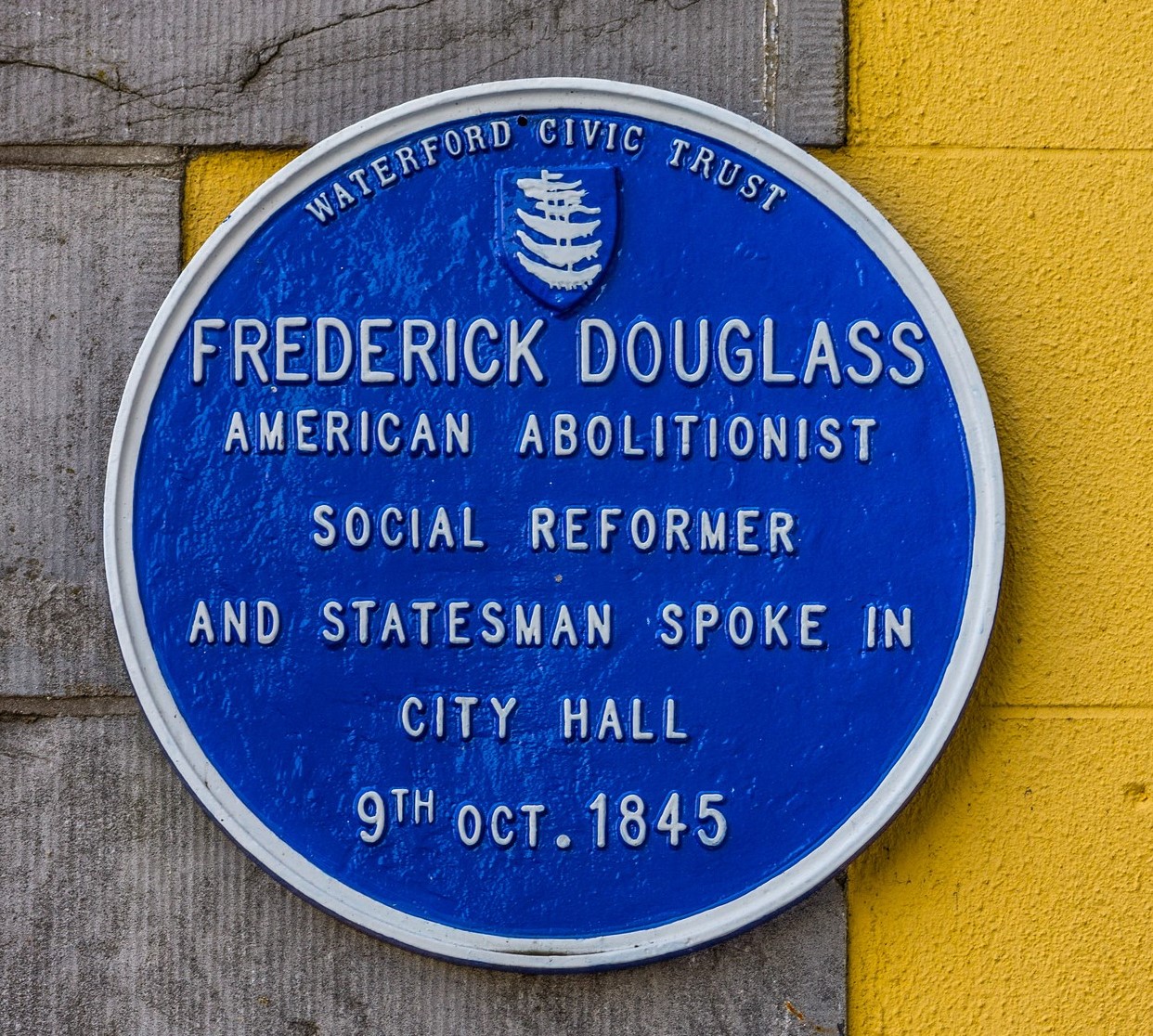

In 1845 the Hibernian Anti Slavery Society was responsible for the visit of the great abolitionist, escaped slave and author Frederick Douglass to Irish shores. Accepting their invitation, he conducted a lecture tour, which in his own words took him from “the hill of ‘Howth’ to the Giant’s Causeway and from the Giant’s Causeway to Cape Clear.” In Dublin he spoke alongside Daniel O’Connell at Conciliation Hall on Burgh Quay, and afterwards was received by the Lord Mayor at the Mansion House. He would go on to speak in Waterford, Belfast, Limerick and Wexford before travelling across the Irish sea to Britain.

“The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” had been published in Boston earlier that year, and while in Dublin a British Isles edition was organised, published by Richard Webb. This sold out almost immediately on the tour, and a second print run of 2,000 was arranged, published in 1846. This was significant as it included a new preface and appendix that had not appeared in the original. Webb, in addition to this re-publication took the lead role in organising and scheduling the lecture tour in Ireland and afterwards wrote to O’Connell to stress how important Douglass was to highlighting the cause in the country, as he had “occasioned deep interest in the anti-slavery cause, and many who never thought on the subject at all, are now convinced that it is a sin to neglect”

Remembered in Dublin at the Irish Film Institute , Eustace Street (former Friends’ Meeting House).

(Photo: Mícheál Mac Donncha )

The three main stays of the society were also involved in other campaigning issues. And the society itself was not only concerned about American slavery. They had campaigned against the use of ‘apprentices’ in the British colonies and after the system was abolished they challenges the use of imported Irish labourers and Chinese ‘coolies’ in the West Indies. Throughout the 1840’s the society met in Dublin at the Committee Rooms on Anglesea Street and also the Royal Exchange (now City Hall). The Famine and Great Hunger from 1845 took up the time of these civic minded members and it appears the activity of the group dwindled somewhat. They did raise the controversial issue of the morality of those who profited from the slave trade providing aid during these years. By 1847 it seems the society did not exist in any meaningful manner, though the individuals did continue to be active in abolitionist organisations until the conclusion of the American Civil War.

Richard Davis Webb died in 1872.

John Haughton died in 1873.

Richard Allen died in 1886.

(The Harold’s Cross house where Richard Allen was born still stands today, though it is currently derelict. It appears on the famous Rocque’s maps of 1756 and 1760, and some local residents have raised concerns that the building should be preserved).

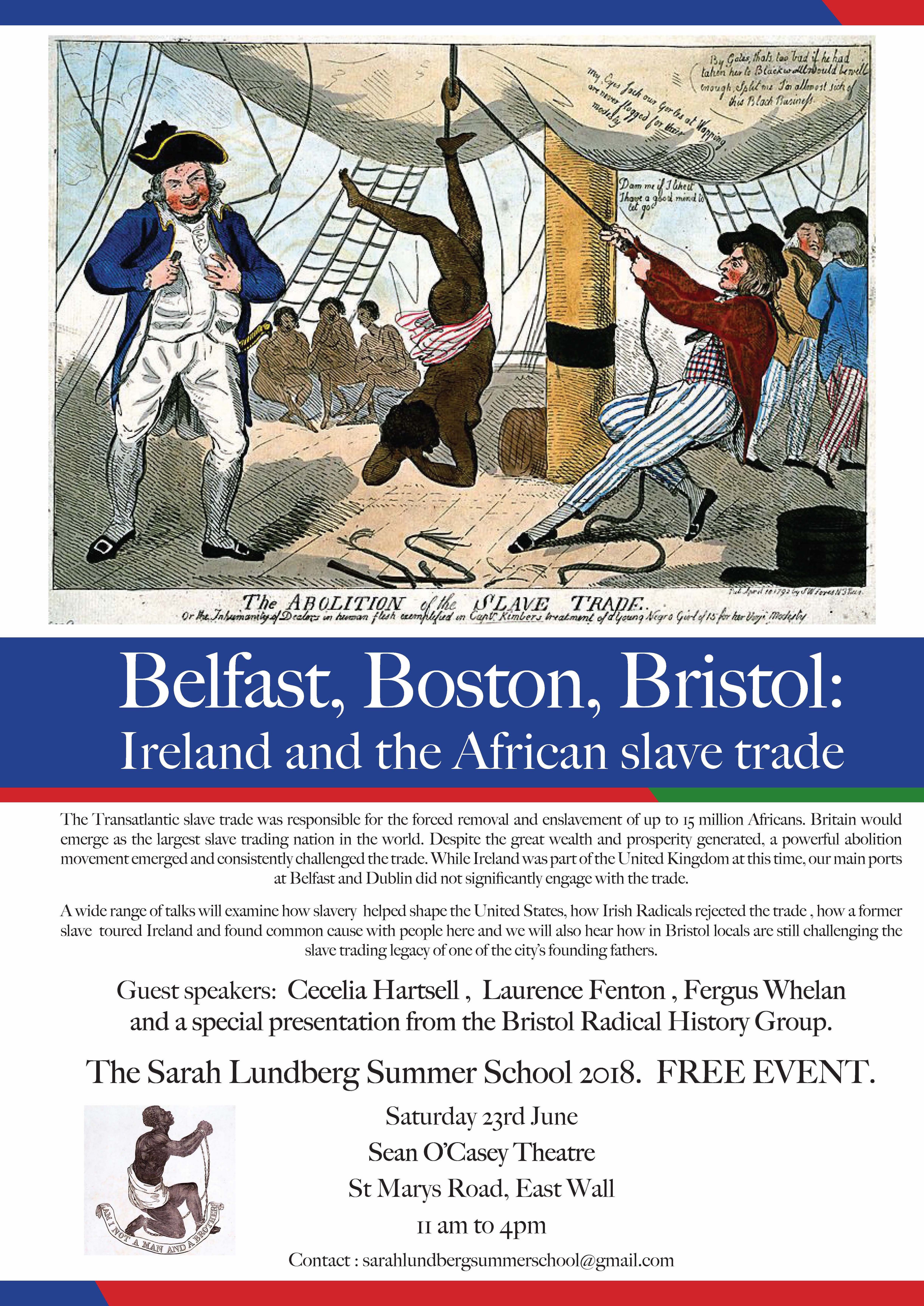

This feature was prepared in advance of the Sarah Lundberg Summer School 2018 which addressed many of the issues relating to the transatlantic slave trade and how Ireland reacted. See poster below.

For clarification , corrections or further information contact:

eastwallhistory@gmail.com